Cultivating Every Child’s Curiosity in the Natural World

By Cindy Workosky

Posted on 2018-04-24

At the NSTA National Conference in Atlanta, I was honored to give the Mary C. McCurdy lecture on young children and their natural curiosity about how the world works. Anyone who has ever spent time with them knows they are born scientists who are curious about the natural world and continuously question, test, and try to make sense of it. Research studies bear this out: “All children bring basic reasoning skills, knowledge of the natural world, and curiosity, which can be built on to achieve proficiency in science” (see Taking Science to School, NRC 2007).

Why, then, do young people become so disinterested in science, often by the time they reach middle school? Even Albert Einstein observed, “It is a miracle that curiosity survives formal education.” Who am I to correct Einstein, but this statement could be modified to say it’s a miracle when curiosity survives formal education. How then do we preserve children’s natural sense of wonder in an era of new standards and change in science education?

Why, then, do young people become so disinterested in science, often by the time they reach middle school? Even Albert Einstein observed, “It is a miracle that curiosity survives formal education.” Who am I to correct Einstein, but this statement could be modified to say it’s a miracle when curiosity survives formal education. How then do we preserve children’s natural sense of wonder in an era of new standards and change in science education?

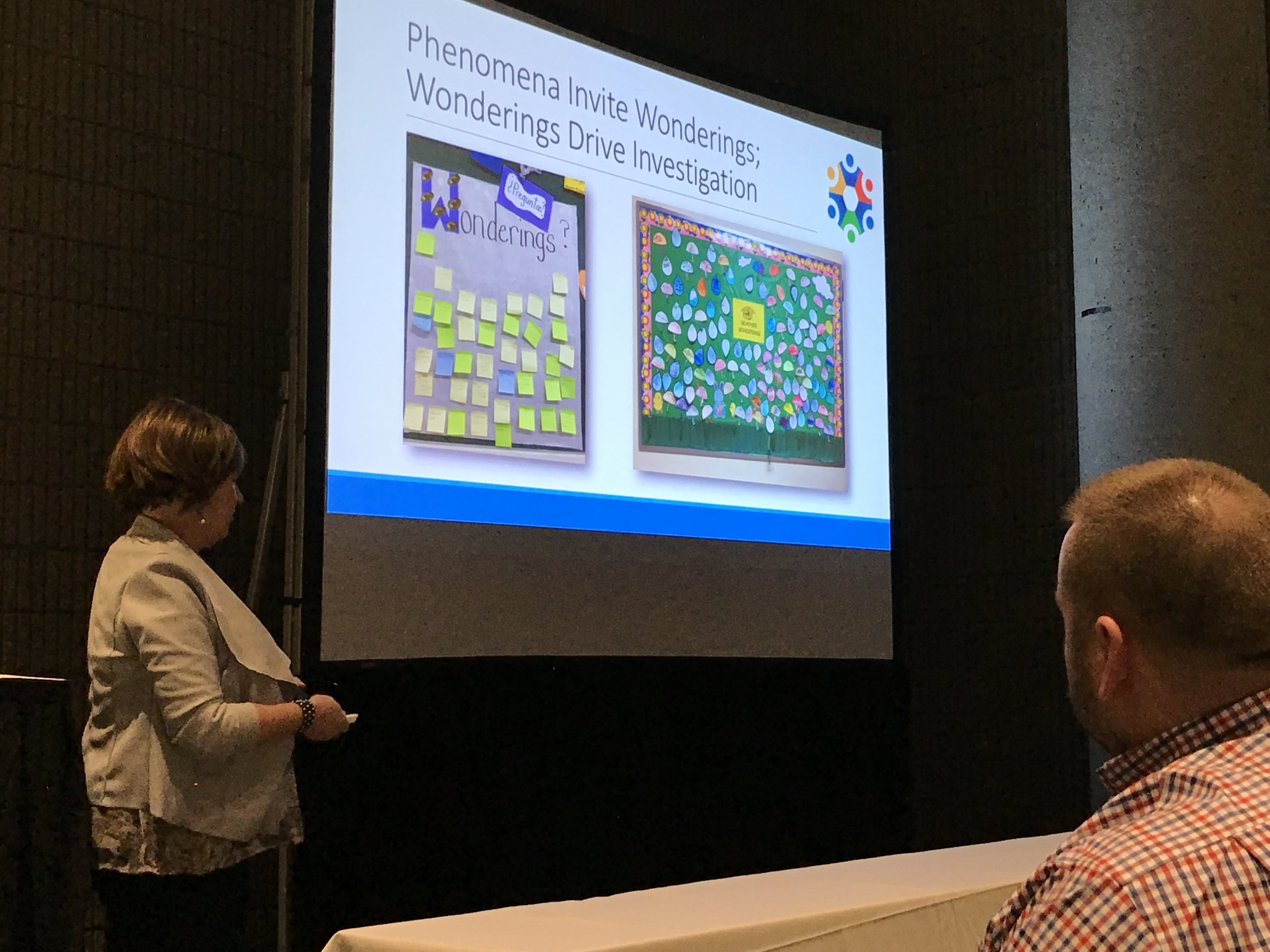

The Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), and the Framework on which they are based, describe an ambitious vision for students’ science learning. Three-dimensional science learning–learning core ideas and crosscutting concepts by engaging in scientific and engineering practices–has major implications for traditional curriculum, instruction, and assessment in science. Because NGSS is intended to reflect scientists’ and engineers’ authentic work, it fundamentally serves as a vehicle for promoting curiosity about phenomena. Focusing on phenomena isn’t merely a way to generate interest and excitement, it also should elicit students’ wonderings in ways that produce an overarching question to guide investigation; create a persistent need to explain/understand; and require sustained investigation (STEM Teaching Tool #28). In other words, an emphasis on phenomena and 3-D learning should by their very nature cultivate curiosity about how the world works.

In this post, I identify two common practices in elementary school science that interfere with children’s curiosity, coupled with instructional practices that nurture wonder. As you read, I encourage you to reflect on your own science teaching and share the work you do to nurture children’s innate curiosity about the natural world.

Shifts in Science Teaching Practices That Support Wonder

It is commonplace in many school settings to pre-teach vocabulary before engaging in investigations and sensemaking. I have referred to this as “the vocabulary dilemma.” As I worked closely with teacher colleagues, I observed that teaching vocabulary by defining terms appears to stem from traditional ELA instruction and the pressures of high-stakes testing. The practice works against curiosity by focusing on pre-defined terms, which are decontextualized, and represents science as little more than a static body of facts. When taught this way, the focus is on reading, writing, speaking, and listening “about” science.

It is commonplace in many school settings to pre-teach vocabulary before engaging in investigations and sensemaking. I have referred to this as “the vocabulary dilemma.” As I worked closely with teacher colleagues, I observed that teaching vocabulary by defining terms appears to stem from traditional ELA instruction and the pressures of high-stakes testing. The practice works against curiosity by focusing on pre-defined terms, which are decontextualized, and represents science as little more than a static body of facts. When taught this way, the focus is on reading, writing, speaking, and listening “about” science.

So what is the alternative? Tying words to meaning requires engaging with and investigating phenomena while accepting “kid talk” until the point in the sensemaking process that children have enough experiences and emerging understanding of the core idea(s) that it makes sense to introduce the scientific term(s). For example, rather than defining force at the beginning of a unit, allow children to explore a variety of forces. Resist introducing the term until they have enough experiences to make the connection between the word and its meaning in context.

This may sound simple, but resisting the urge to explain and define vocabulary during the act of teaching requires intentional planning for opportunities for children to participate in sensemaking: reading, writing, speaking, and listening “for” science (NRC 2014). Remember that NGSS implementation requires a phenomena-based context in which students themselves are interested and motivated to investigate, explain, and understand.

My next example of common practices that inhibit children’s natural curiosity may surprise you. It’s hands-on activities, something a teacher colleague calls “snacks and crafts” science. It is deceiving because when kids are doing activities, they appear to be engaged and having fun. So how does “activity-mania” counteract a sense of wonder? When taught in this way, science may indeed be exciting; however, an activity focus is often driven by science topics or themes and does not build toward a coherent science content storyline (Reiser 2013).

My next example of common practices that inhibit children’s natural curiosity may surprise you. It’s hands-on activities, something a teacher colleague calls “snacks and crafts” science. It is deceiving because when kids are doing activities, they appear to be engaged and having fun. So how does “activity-mania” counteract a sense of wonder? When taught in this way, science may indeed be exciting; however, an activity focus is often driven by science topics or themes and does not build toward a coherent science content storyline (Reiser 2013).

Additionally, collections of fun activities rarely involve students in scientific practices, such as modeling, arguing from evidence, and constructing explanations. Kids may find out “about” cool science facts or see “flash bang” demonstrations, but they are not participating productively in scientific discourse and practices that are essential for sensemaking. So children’s excitement about activities tend to wane as the activity concludes instead of persisting across a unit of study, driven by students’ need to explain and understand some aspect of how the world works.

As we progress in the hard work of NGSS implementation, it is important to consider that we have all been rendered novices in some way by the ambitious new vision for students’ science learning. In the end, however, teachers are the ones left to enact the instructional practices that support this vision, often in the isolation of our own classrooms. Change requires us to be curious, not only about the NGSS, but also about how children learn and how our instructional practices impact their learning.

Additionally, we must be willing to share what we find as we engage in inquiry into science teaching and learning with others. In her book A Sense of Wonder, marine biologist and conservationist Rachel Carson describes her wish for every child as an indestructible sense of wonder that lasts a lifetime and protects from the disenchantment that comes with age. My wish for you as an educator is that you, too, will never lose your sense of wonder.

I welcome feedback on your experiences with making these challenging shifts away from pre-teaching vocabulary and activity-mania to tying science words to meaning, and using phenomena to promote coherence across investigations. Please comment below…

Carla Zembal-Saul is a professor of science education and the Kahn Professor of STEM Education at Penn State University. A former middle school science teacher with a background in biology, she is co-author of the book What’s Your Evidence? Engaging K–5 Students in Constructing Explanations in Science. Zembal-Saul’s research investigates instructional practices and tools that support preservice and practicing elementary teachers in engaging children productively in scientific practices and discourse with an emphasis on sensemaking about natural phenomena. She is deeply invested in practitioner inquiry and video analysis of practice as mechanisms for advancing teacher learning and development. In 2015, Zembal-Saul was recognized as a NSTA Fellow, and she served on the National Academies of Sciences consensus panel that produced the report, Science Teachers’ Learning: Enhancing Opportunities, Creating Supportive Contexts.

Carla Zembal-Saul is a professor of science education and the Kahn Professor of STEM Education at Penn State University. A former middle school science teacher with a background in biology, she is co-author of the book What’s Your Evidence? Engaging K–5 Students in Constructing Explanations in Science. Zembal-Saul’s research investigates instructional practices and tools that support preservice and practicing elementary teachers in engaging children productively in scientific practices and discourse with an emphasis on sensemaking about natural phenomena. She is deeply invested in practitioner inquiry and video analysis of practice as mechanisms for advancing teacher learning and development. In 2015, Zembal-Saul was recognized as a NSTA Fellow, and she served on the National Academies of Sciences consensus panel that produced the report, Science Teachers’ Learning: Enhancing Opportunities, Creating Supportive Contexts.

This article was featured in the April issue of Next Gen Navigator, a monthly e-newsletter from NSTA delivering information, insights, resources, and professional learning opportunities for science educators by science educators on the Next Generation Science Standards and three-dimensional instruction. Click here to access other articles from the April issue. Click here to read more in the April issue. Click here to sign up to receive the Navigator every month.

Visit NSTA’s NGSS@NSTA Hub for hundreds of vetted classroom resources, professional learning opportunities, publications, ebooks and more; connect with your teacher colleagues on the NGSS listservs (members can sign up here); and join us for discussions around NGSS at an upcoming conference.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2018 STEM Forum & Expo

Dive into Three-Dimensional Instruction Workshop

2018 Area Conferences

2019 National Conference

Follow NSTA

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the National Science Teaching Association (NSTA).