#OrganelleWars: A Model for Using Social Media in the Science Classroom

By Guest Blogger

Posted on 2016-05-05

Given the current political fervor over the candidacies of the people attempting to become our next president, now seemed like a good time to revisit one of the most successful projects I have had the good fortune of incorporating into my freshman biology classroom.

Launching a Model Organelle Campaign

In the fall of 2011, I had reached the point of the school year when it was time to start teaching my freshman biology students about the cell and its organelles. In my 14 years of teaching to that point, I had tried all types of different approaches to try and bring the cell alive for my students. I had tried direct instruction, having students build models of the cell, asking them to make analogies comparing the cell to a city, having them give presentations on individual organelles, even putting on a pretend radio show in class, and finally making fake Facebook pages on paper for each organelle. So as I prepared to begin the cell unit for the fourteenth time, I went to the Internet looking for inspiration (teachers are nothing if not good thieves, after all). One project I discovered came from Marna Chamberlain at Piedmont High School in California. The idea was to have students run an election campaign to get an organelle elected the most important organelle in the cell. The project involved promoting an organelle in class through the use of posters, brochures, and a speech. In addition to promoting their own organelle, students also had to smear at least five other organelles. This last requirement was designed, of course, to ensure that students researched the functions of other organelles in the cell as they worked on promoting their own. After a correspondence with Ms. Chamberlain, I decided to give the project a try.

Before getting started, I made one tweak to the project from its original incarnation, and that was to add a social media component to it. I had noticed, as most educators I work with had at that point, that students were often more preoccupied with their social media accounts than they were with their school work. My thought was that if I could bring school to where students were already spending a lot of their time, I might be able to capture their interest better than I had been able to in the past. The requirement for the social media component, which was optional for students to create, was that any account had to be a fake account in the name of the organelle. This was important in keeping the identities of my students anonymous and in keeping in line with the social media policy of my school district.

Moderate Success in Year One

The first year of the project went pretty well. My students made some great campaign posters and flyers, to the point that my classroom was covered in both promotional and smear posters. The social media component was fun, but the only people following any students’ accounts on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or Tumblr, were other students or myself. The proof of the effectiveness of this project, of course, would be in my students’ results on their end-of-unit assessment. I was concerned that although the project was fun, that perhaps they had not learned as much about cell organelles as in the past, since they had only been required to focus on six organelles. Students had been made aware that they were responsible for being able to identify and know the function of all of the organelles assigned in the project, but I was still nervous. In the end, however, students performed as well on the cell unit test in 2011 as they had in all my previous years, only this time they enjoyed and became engaged with the content. The project was successful enough that I decided to stick with it and try it again the following year.

Year Two: The Scientific Community Embraces the Concept

One of the keys to the project in 2012 was that it was a presidential election year, and it was the first campaign to truly use social media. My students were already naturally excited about the election process. The classroom was buzzing with activity, as students started creating campaign t-shirts, buttons, and stickers, in addition to the posters and brochures. They also created their Twitter accounts for their organelles, such as @GolgiBody2012 and @MightyMito42.

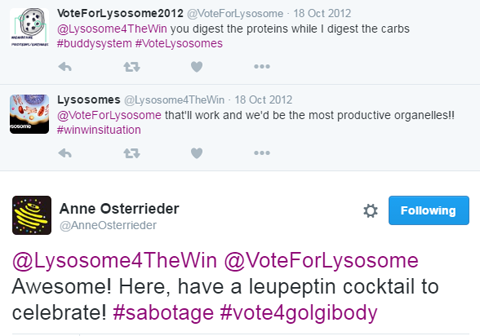

Then a funny thing happened. Someone I didn’t know started tweeting with my Golgi Body group. My first reaction was of course to determine who this person was, and I was initially quite nervous that a complete stranger had somehow found our little project on Twitter. But my apprehension turned to delight when the stranger turned out to be Dr. Anne Osterrieder (@AnneOsterrieder), a plant biologist who is an expert on the Golgi Body and a lecturer/researcher at Oxford Brookes University in England. Apparently Dr. Osterrieder had found one of my students’ Golgi Body Twitter accounts during a Twitter search for any relevant new tweets with content related to her organelle of interest.

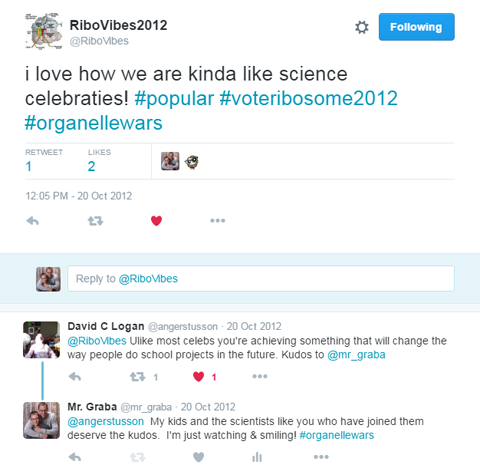

From those initial tweets, the project exploded. A colleague of Dr. Osterrieder’s at Oxford Brookes University, Dr. John Runions (@JohnRunions), also began tweeting with my students. Dr. Runions gave our project the hashtag #organellewars on Twitter. Since then, that has become the name this project goes by in my classroom and online. Dr. Runions also has his own BBC radio show, where he goes by the alias Dr. Molecule, which he used to talk about my students and their project on one of his shows. Dr. David Logan (@angerstusson) from the Universite d’Angers in France, a plant biology researcher and self-described mitochondriac, also began tweeting with my students, helping to promote the mitochondria groups and smear the others. Soon other biologists from all over North America and Europe began tweeting with my students. The buzz the project created within the classroom and the school was incredible. My students were tweeting about organelles with scientists from Europe late at night on the weekend. In the past I had been lucky to get them to think about organelles at all other than when they were physically present in the classroom, but now they were actively engaged in learning about organelles beyond the four walls of my classroom, on a weekend, because they wanted to!

A Lesson in the Nature of Science

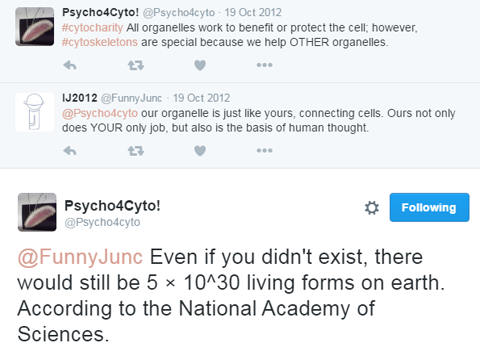

The results of the project the second time around went far deeper than I ever expected. Not only did my students learn about organelles, they learned far more important lessons about social media and science as well. The fact that this time around with the project there were experts on organelles interacting with my students, calling them out when they posted erroneous information, or asking them questions that inspired my students to d

ig deeper after they posted very superficial tweets regarding their organelle, gave my students an authentic audience. They were motivated to make sure that what they were posting was legitimate, appropriate, and able to be cited with reliable resources. I heard discussions among students about having been called out by a scientist online after having posted incorrect information about an organelle and needing to be careful about what they typed before hitting the “Tweet” button. Learning to have that filter before hitting “Tweet” or “Post” is an important skill for this generation to learn at a young age.

One point that I made very early on, after people from around the globe began interacting with us, was the far-reaching and very public nature of social media such as Twitter. Teenagers in general have a tough time grasping this concept. I think this is generally because the only people who interact with them online are typically their very limited social circle. That does not mean, however, that others outside of their small group of friends cannot see what their online activity looks like. It is especially important for the current generation of students to learn this lesson at an early age. College admissions counselors and future employers look at social media accounts to get a better understanding of the people they are admitting or hiring. Something that excites me is that these students now have a positive social media footprint to share with anyone who wants to start looking at their social media accounts.

Students See Scientists in a New Light

My students’ perceptions of scientists also changed from the stereotypes they brought with them into my classroom at the beginning of the year. Most students had the preconceived idea that scientists were boring old men in lab coats and goggles hidden away in a sterile lab all day long. By the end of the project, they were able to see that many scientists are actually vibrant, witty, young men and women who love science and their research, but also like doing the same kinds of things my students and everyone else enjoy.

I suspect that this coming year will be a fantastic time to attempt running this project. If this project sounds like something you might be interested in attempting some time in the future, I can be reached via email at bgraba@d211.org or @mr_graba on Twitter.

I suspect that this coming year will be a fantastic time to attempt running this project. If this project sounds like something you might be interested in attempting some time in the future, I can be reached via email at bgraba@d211.org or @mr_graba on Twitter.

Guest Blogger Brad Graba is an AP Biology Teacher at William Fremd High School in Palatine, Illinois.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

5th Annual STEM Forum & Expo, hosted by NSTA

- Denver, Colorado: July 27–29

2017 Area Conferences

- Baltimore, Maryland: October 5–7

- Milwaukee, Wisconsin: November 9–11

- New Orleans, Louisiana: November 30–December 2

National Conferences

- Los Angeles, California: March 30–April 2, 2017

- Atlanta, Georgia: March 15–18, 2018

- St. Louis, Missouri: April 11–14, 2019

- Boston, Massachusetts: March 26–29, 2020

- Chicago, Illinois: April 8–11, 2021

Follow NSTA

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the National Science Teaching Association (NSTA).