Podcasting in the Science Classroom

By Debra Shapiro

Posted on 2019-04-03

Photo by Terri Reutter

“When my students are unable to attend a field trip, I typically create a podcast, so those students can listen to what was learned. Then I post the podcast in Google Classroom, so they can access it,” says Kurtz Miller, who teaches geology, physics, and physical science at Wayne High School in Huber Heights, Ohio. He says podcasts work well “for my upper-level, college-credit geology students because it helps them really digest and consider what was said…It gives them a firsthand account and additional information besides other students’ notes.”

Miller gets permission in advance from the speakers on the field trips to record their talks. He uses a mono digital voice recorder with built-in USB. “It costs just [less than] $50 [and] records in MP3 audio format,” he explains. “It’s an example of something a teacher without a lot of tech savvy could do, a starting point for teachers to try.”

“I first started using student-made podcasts along with a sixth-grade yearlong project about famous scientists,” says Ramona Jolliffe Satre, former fifth- and sixth-grade science teacher and now a K–12 instructional science coach for Ogden Community Schools in Ogden, Iowa. Each month, “chosen students presented orally to their class about a famous scientist in history. This usually involved a slide presentation to guide their talk. This oral presentation also involved the student using a mic to present; another learning experience.”

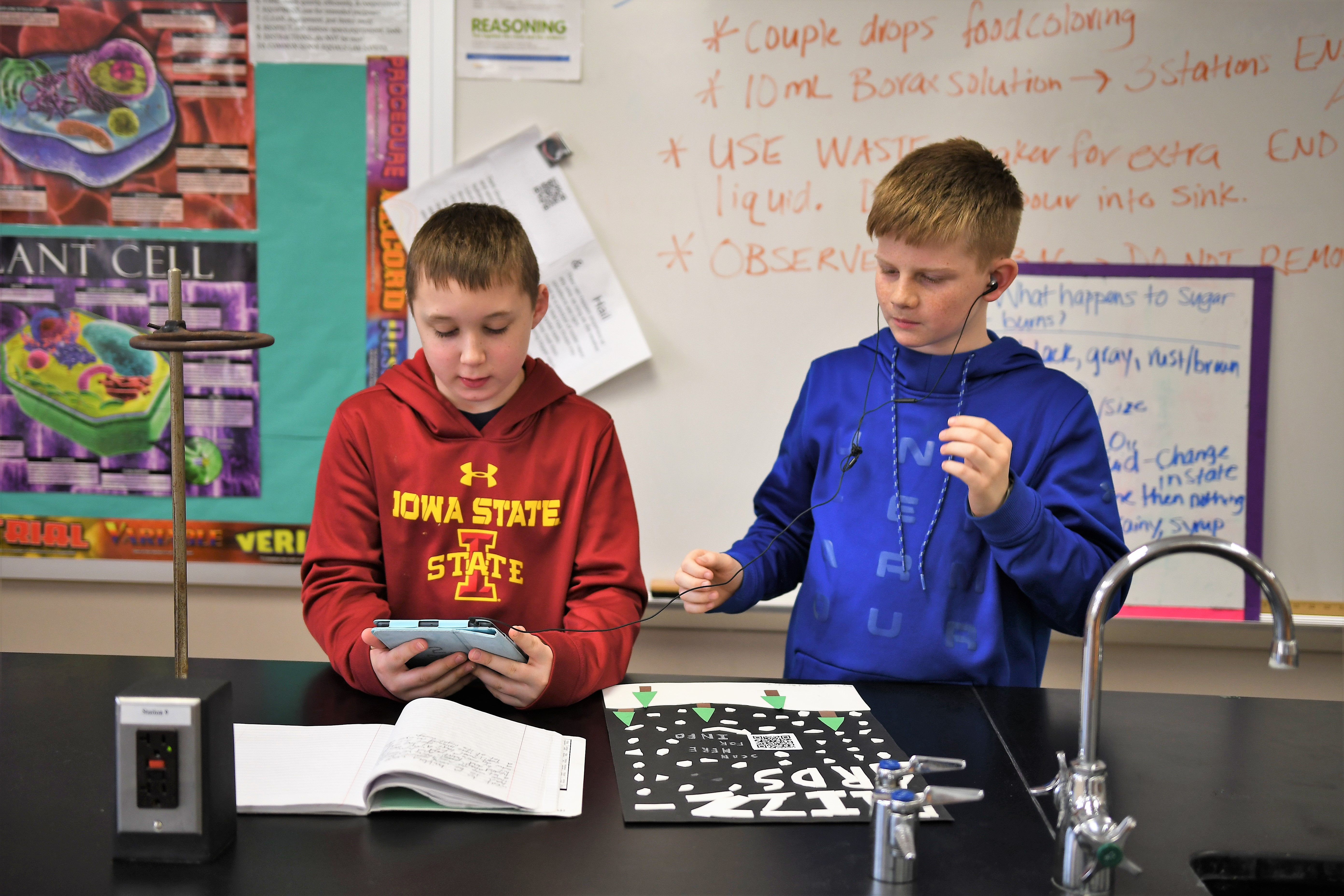

Next, her students “record and upload a podcast, allowing peers absent from class to share in the presentation. The podcast is logged in their Google Classroom for future reference at assessment time. Students also enjoy using the podcasts for reviewing the information,” Satre maintains.

Her students also produce three- to five-minute podcasts to accompany “a poster about a classroom concept. We just completed posters about natural disasters in class. Each poster has a [two-dimensional barcode] on it that attaches a student-made podcast offering further information about the natural disaster. We share these posters in our hallways and community locations like the public library,” she relates. “It gets the community involved and gives students another audience,” she notes.

“I encourage students to write a script first, to connect the written word to the brain. Repetition helps them remember,” Satre contends. She emphasizes the importance of “talk[ing] like scientists” and says podcasting “is a way to reinforce that, [having] correct grammar…a presentation voice.”

Because of the ease and popularity of texting, “a lot of students are not as verbal as they once were. Students need to practice talking. In Iowa, part of our literacy standard is speaking. Students have to be able to communicate for their careers,” Satre asserts.

“I’ve been podcasting as an instructor and have had students create podcasts,” reports Laura Guertin, professor of Earth science at Penn State Brandywine in Media, Pennsylvania. She says she was sold on podcasting after attending a summit on undergraduate science education and hearing from employers of recent graduates that “students’ weakest skill is their ability to listen.”

Guertin contends that students “don’t get enough opportunities to show their knowledge matters and makes a difference in others’ learning. Students can be teachers and students at the same time.” For example, her students created podcasts about tree identification for Ridley Creek State Park in Newtown Square, Pennsylvania, and podcasts focusing on basic geology and sustainability for the Pennsylvania Earth Science Teachers Association.

Podcasting is “a tool to enhance learning of content without it taking away from the objectives of the course, without having technology be a barrier or a burden,” Guertin observes. “It can help students learn a transferrable skill outside [my] Earth science courses… When students create podcasts, they can post them on their LinkedIn pages to impress employers.”

Allowing students to choose topics of interest related to the course “gives them ownership of the project,” Guertin points out. She has her students work with librarians to research their scripts. “The information has to be current, reliable, and unbiased. Students learn how to evaluate good sources and how to write a script…I have them listen to examples of [quality] podcasts and review [one another’s] scripts and podcasts, which helps improve their writing and recording abilities.”

Guertin also records podcasts for her students. “They can listen to them in the car or while riding on buses,” she notes. “I put in natural breaks so students can pause the podcast and return to it later.”

She will also pose the same questions she would in class during the podcast. “They can hit pause to think about the answer, then restart the podcast. It gets them to think and apply what they’re learning,” she maintains.

‘Another Podcast Boom’

While noting that technological advancements in schools have made it easier for students to record audio and video together, students are making quality audio podcasts now mainly for “car rides and workouts,” reports science teacher Brian Bartel, co-host of NSTA’s Lab Out Loud podcast series. He and science teacher co-host Dale Basler speculate that “not a lot of students are listening to audio podcasts yet.”

However, the co-hosts foresee “another podcast boom now because you can make them with many devices. The apps allow it,” Basler asserts. “Video is king, but telling a story using audio gets students thinking about all the aspects.”

“This is important because you can’t mow the lawn while watching video, but you can while listening to a podcast,” Bartel points out.

Teachers are having students listen to Lab Out Loud podcasts “and put their images to the narration, which allows them to synthesize and interpret the content and remix it,” reports Basler. “This results in a deeper understanding for students.”

The co-hosts agree that having students make their own podcasts “is not done enough,” perhaps because teachers “have to give up control of the classroom. It’s an isolating task, but gives students agency if done right.”

“I love to hear students ask, ‘Can I do a lab report in a different way?’ There are many ways” for students to showcase their learning, including podcasts, Bartel notes. “Trust students to make the right decision to express their learning, and have a good microphone if you’re doing this on a regular basis.”

“Make sure [you convey] what you want students to learn [when they make podcasts]. The content is more important than the technology; learning outcomes are more important,” Basler emphasizes. He adds that schools and teachers also are responsible for “giving students guidelines on making meaningful content.”

Logistics is a factor. “At the elementary level, you may have 20 to 30 students trying to record in one classroom. We don’t have schools designed for this,” Bartel points out. Teachers may need to “stagger these podcasts so not all students are recording them at the same time.” He also advocates finding ways to diminish background noise by “creating recording tents to isolate sound, or having students record in the hallway.”

Teachers also need to decide how to share their students’ podcasts with other students and teachers, parents, or the public. Basler urges teachers to ask themselves, “Where will the content end up? Does it follow a student forever?”

This article originally appeared in the April 2019 issue of NSTA Reports, the member newspaper of the National Science Teachers Association. Each month, NSTA members receive NSTA Reports, featuring news on science education, the association, and more. Not a member? Learn how NSTA can help you become the best science teacher you can be.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the National Science Teaching Association (NSTA).