Using Primary Sources as Anchoring Phenomena

By Cindy Workosky

Posted on 2018-04-24

I think the best part of attending NSTA’s national conferences is having the opportunity to learn so much from every person you meet. The sheer number of so many likeminded educators in one place can seem overwhelming, but the opportunity to learn from them all is one that can’t be missed.

After leaving the 2017 NSTA National Conference in Los Angeles with so many strategies to implement in my classroom, I decided to share about the new strategies I had incorporated in my classroom. I chose to discuss my use of historical primary sources in the science classroom; specifically, how they could be used as anchoring phenomena in an NGSS classroom.

My session, Using Primary Sources as Anchoring Phenomena, was inspired by my participation in the Library of Congress (LOC) Summer Teacher Institute in 2015. The LOC suggests using primary sources in education because they engage students, develop their critical-thinking skills, and help them construct knowledge. Since attending the Summer Teacher Institute, I have become much more familiar with the NGSS.

The connections between the benefits of using primary sources and the vision of science education outlined in the National Research Council’s A Framework for K–12 Science Education have resonated with me. For example, the LOC says engaging students with primary sources helps them “construct knowledge as they form reasoned conclusions, base their conclusions on evidence, and connect primary sources to the context in which they were created, synthesizing information from multiple sources.” These ideas closely align with the elements of the Science and Engineering Practices, Engaging in Argument from Evidenceand Constructing Explanations.

When using primary sources in my own classroom, I usually found that students were engaged in determining what the documents showed, and I heard students say repeatedly that they had never done anything like this in a science classroom. When I began my transition to a NGSS classroom, it was easy to see that historical primary sources could still play a role in instruction.

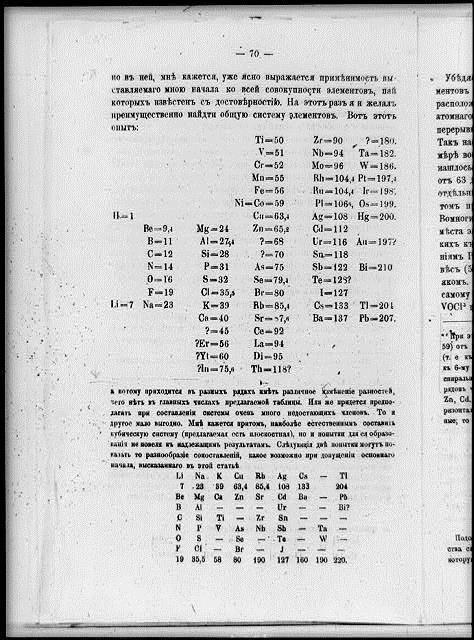

When my conference session began, attendees first chose a primary source from a table filled with images, manuscripts, and models. When I asked if anybody would share why they chose a particular image, one teacher displayed the image of Mendeleev’s First Periodic Table and said something like “This interested me because I think it is the first periodic table, and I really love chemistry.” Another teacher displayed an image of a sideways house with a tree through it, and related how she had just witnessed this happening to a house in her area after a tornado hit it. It became instantly clear to the group that one benefit of using primary sources is the strong personal connection with the content that can be established.

Mendeleev’s first periodic table

After our initial discussion, we reviewed some basic definitions of primary sources, secondary sources, and the terms of copyright and fair use in educational settings, which are necessary when discussing the use of primary sources in the classroom. We also explored the Primary Source Analysis Tool, created by the LOC as a way to analyze and record ideas about a primary source being explored.

We then focused on how we could use primary sources as anchoring phenomena. We defined phenomena as “observable events that occur in the universe and that we can use our science knowledge to explain or predict,” the definition from the resource Using Phenomena in NGSS-Designed Lessons and Units. Whenever we define phenomena in this way, I confess I always wonder how primary sources can count as phenomena: After all, they are not observable events; they’re old documents or images!

We then focused on how we could use primary sources as anchoring phenomena. We defined phenomena as “observable events that occur in the universe and that we can use our science knowledge to explain or predict,” the definition from the resource Using Phenomena in NGSS-Designed Lessons and Units. Whenever we define phenomena in this way, I confess I always wonder how primary sources can count as phenomena: After all, they are not observable events; they’re old documents or images!

While primary sources aren’t directly observable, natural events, they are tools that help us witness natural phenomena that may not be observable otherwise. They may help us observe phenomena from the past, as do images of rivers that have changed course over time. Or they may help us witness phenomena that are too large or small to see directly.

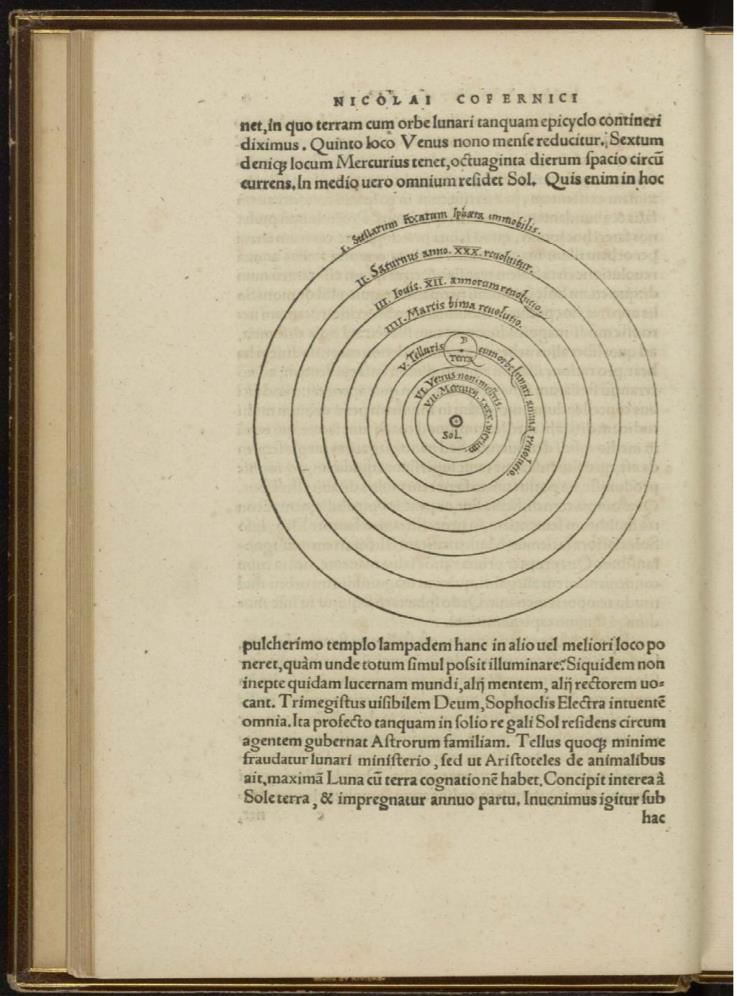

To explore this idea, teachers in my session used primary sources to develop questions that could be used to create a driving question board in a middle school Earth science class. They began by independently observing, analyzing, and asking questions about a historical model of the solar system. Then we jigsawed the various images, shared our observations and reflections, and developed new questions related to the set of primary sources. The teachers engaged in lively discussion as they tried to determine which chronological and/or ideological order the images belonged in. Finally, I asked them to choose one of their questions to share with the group that they thought would best help answer our driving questions: “Has the movement of bodies in the solar system changed over time? Why have the models of the solar system changed over time?” Their questions ranged from “What evidence did the astronomers have to create their model?” and “What changes in technology helped provide evidence?” to specific questions about what the different parts of the models represented.

Ptolemaic Concept of the Universe

Copernicus’ Sun-Centered Model of the Cosmos

The final moments were devoted to exploring how student understanding of the Nature of Science can be supported through the use of primary sources. Appendix H of NGSS outlines eight understandings of the Nature of Science, with grade-banded elements associated with each. While we can establish understandings of the Nature of Science in many ways throughout instruction, one method involves explicit reflection on those understandings by using case studies from the history of science.

Despite technical difficulties with my computer and missing my partner presenter, I’m happy I had the opportunity to share some ideas from my classroom experience with other teachers. My session resources can be found at tinyurl.com/PSNSTA18.

I would love to hear your feedback.

- How have you used primary sources in your classroom?

- What resources have you used to find primary sources?

- Do you have any ideas of phenomena that can be represented using historical primary sources?

Comment below and I’ll be sure to respond.

References

(1513) An illustration of the Ptolemaic concept of the universe showing the earth in the center. , 1513. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2007681147.

Copernicus, N. (1543) Nicolai Copernici Torinensis De revolvtionibvs orbium cœlestium, libri VI. Habes in hoc opere iam recens nato, & ædito, studiose lector, motus stellarum, tam fixarum, quàm erraticarum, cum ex ueteribus tum etiam ex recentibus obseruationibus restitutos: & nouis insuper ac admirabilibus hypothesibus ornatos. Habes etiam tabulas expeditissimas, ex quibus eosdem ad quoduis tempus quàm facillime caculare poteris. Igitur eme, lege, fruere. Line in Greek. Norimbergæ, apud Ioh. Petreium. [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/46031925.

Mendeleyev, D. I. (1869) First Periodic Table of Chemical Elements Demonstrating the Periodic Law. Russia, 1869. [Published] [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/92517587.

National Research Council. 2012. A Framework for K–12 Science Education: Practices, Crosscutting Concepts, and Core Ideas. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13165.

Why Use Primary Sources? Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/teachers/usingprimarysources/whyuse.html.

Brianna Reilly is a high school biology teacher at Hightstown High School in New Jersey’s East Windsor Regional School District. Outside of the classroom, Reilly is a member of Achieve, Inc.’s Science Peer Review Panel and one of NSTA’s Professional Learning Facilitators. She has been honored with NSTA’s 2017 Maitland P. Simmons Memorial Award. Reilly earned her B.S. in biology from The College of New Jersey, and will complete her M.S. in science education this summer at Montana State University. Follow her on Twitter: @MsB_Reilly.

This article was featured in the April issue of Next Gen Navigator, a monthly e-newsletter from NSTA delivering information, insights, resources, and professional learning opportunities for science educators by science educators on the Next Generation Science Standards and three-dimensional instruction. Click here to read more from the April issue. Click here to sign up to receive the Navigator every month.

Visit NSTA’s NGSS@NSTA Hub for hundreds of vetted classroom resources, professional learning opportunities, publications, ebooks and more; connect with your teacher colleagues on the NGSS listservs (members can sign up here); and join us for discussions around NGSS at an upcoming conference.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2018 STEM Forum & Expo

Dive into Three-Dimensional Instruction Workshop

2018 Area Conferences

2019 National Conference

Follow NSTA

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the National Science Teaching Association (NSTA).