NSTA Press Excerpt

Reframing Instruction With Universal Design for Learning

By Delinda van Garderen, Cathy Newman Thomas, and Kate M. Sadler

NSTA Press publishes high-quality resources for science educators. This series features just a few of the books recently released. This excerpt is from Universal Design for Learning Science, by Delinda van Garderen, Cathy Newman Thomas, and Kate M. Sadler, edited for publication here. NSTA Press publications are available online at the NSTA Bookstore.

NSTA Press publishes high-quality resources for science educators. This series features just a few of the books recently released. This excerpt is from Universal Design for Learning Science, by Delinda van Garderen, Cathy Newman Thomas, and Kate M. Sadler, edited for publication here. NSTA Press publications are available online at the NSTA Bookstore.

If you are a teacher or an administrator, it would not be surprising to find that the learners you interact with are diverse in many ways. Based on national demographic statistics for public schools (McFarland et al. 2017), you most likely have, or are going to have, learners who have a disability (13%), such as children who are diagnosed with learning disabilities, autism, emotional and behavioral disorders, or intellectual disabilities; students who are English language learners (9.4%); or learners who come from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds (50%). Furthermore, you have, or are going to have, students who vary tremendously in their ability to learn, their interests, their skills, their preferences, and so on.

Maybe you have heard or read about the call in the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) that science is to be for “all students” (NGSS Lead States 2013, Appendix D). But who exactly are “all students”? According to the Every Student Succeeds Act (2015), all students represents a diverse group of learners, including those who are culturally and linguistically diverse, have a disability, and/or have limited English proficiency. Furthermore, it includes those who are considered gifted and talented. It is important to recognize that although there are many categories of diversity, learners may actually belong to multiple groups of diversity, and each group is a mixed group of learners with a variety of differences (NGSS Lead States 2013, Appendix D).

STOP AND CONSIDER …

Before you read the rest of this chapter, take a moment to think about the students you are currently working with or may be working with in the future. Write down a list of ideas about them in response to the following questions. Who are your diverse learners? How are they alike? How are they different? What strengths do they bring to science? What challenges do they experience when learning science? As you think about your students, answer the following questions: Do you believe all your students can engage in science and learn challenging science concepts? Do your expectations differ for different students or groups of students? Do you feel comfortable teaching science to all of your students?

Science for All?

According to the NGSS, not only is science to be for “all students,” but there is also the expectation that teachers are to create learning opportunities that enable all of their students to meet “all standards” (NGSS Lead States 2013, Appendix D). Historically, expectations have varied for different groups of learners’ participation in science, and not all learning opportunities have been equitable for all learners (McGinnis 2003). Here’s the thing…there is a lot of research (e.g., Aydeniz et al. 2012; Brusca-Vega, Brown, and Yasutake 2011; Therrien et al. 2011; 2014) that suggests that—given equitable learning opportunities—diverse learners are actually quite “capable of engaging in scientific practices and meaning-making in both science classrooms and informal settings” (NGSS Lead States 2013, Appendix D).

STOP AND CONSIDER …

Can instruction be designed in such a way as to promote access to high-level, inquiry-based science learning for all learners, regardless or even in spite of their diverse needs?

We would not be surprised if many of you find it challenging to answer the above question. We suspect you are reading this book because you may be wondering how to teach science to such diverse learners! Guess what? We have wondered about this too—a lot. Therefore, the purpose of this chapter is to help you think about your instruction for diverse learners and how to use Universal Design for Learning (UDL) to (re)frame your instruction. This chapter outlines the framework of UDL, which can provide you with a systematic, intentional, and structured way to improve your instruction. With UDL, you can be more effective and impactful in how you plan for, include, and support diverse learners in doing meaningful science in every lesson and activity.

What Is Universal Design for Learning?

The concept of UDL came from ideas originally developed by architects who recognized that many buildings and equipment were not accessible or easy to use for all individuals; in other words, there were many barriers for users (McGuire, Scott, and Shaw 2006). As a result, architects advocated that all users should be considered, proactively, in the planning and design stages of buildings, public use areas, equipment, and technology designed for public use. The designers embedded “solutions” into buildings and equipment to enable full access and use for everyone. Ronald Mace is credited with developing the concept that came to be called “universal design” (McGuire, Scott, and Shaw 2006).

Interestingly, when users with varied and diverse needs were considered during planning, it was found that these solutions were also beneficial for many others beyond those initially identified. For example, accessibility standards, such as a curb cut or ramps, may benefit a worker carrying boxes as well as a person in a wheelchair. People interested in the learning sciences borrowed the concept of universal design and worked to adapt it for the field of education. So, too, UDL promotes the idea of considering the needs of a wide range of learners as you plan and design materials and instruction (Gronneberg and Johnston 2015). Guiding this process is the UDL framework (Rose and Meyer 2002).

Before moving forward, it is important to acknowledge that educational researchers have been developing ideas about UDL for more than 20 years. The particular UDL framework used in this book is grounded in work developed by researchers at the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST;,2018). There are numerous updated resources and materials that expand on ideas that we share; they can be found on CAST’s website or on the website of the National Center on Universal Design for Learning. We strongly encourage you to check them out.

The UDL Framework: Principles, Guidelines, and Checkpoints

At the heart of the UDL framework are three principles, which draw from broad research findings in fields such as neuroscience and cognitive science (CAST 2018). Essentially, there are areas in our brain that are connected to recognition networks, which guide the “what” of learning; strategic networks, which guide the “how” of learning; and affective networks, which guide the “why” of learning. What the research suggests is that our instruction needs to address all three networks (CAST 2018; Rose and Strangman 2007). In particular, we need to focus on helping learners gather ideas and organize those ideas in a meaningful way, as well as provide ways for the learners to express their ideas, in a manner that engages them in the topic and supports them to stay motivated and engaged throughout the learning experience (CAST 2018; Rose and Strangman 2007).

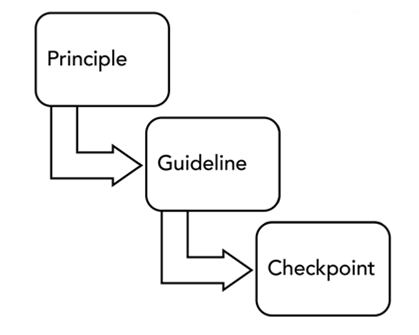

Within each principle are three guidelines (see Figure 2.1 below), which have two key functions. First, each guideline highlights where potential barriers may exist that can prevent learners from accessing learning. Second, each provides concrete, evidence-based solutions (the checkpoints) to reduce or remove barriers that may be preventing diverse learners from accessing instruction and learning. Remember, NGSS calls for “all students, all standards,” and for students with disabilities, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (2004)—and, more recently, the Every Student Succeeds Act (2015)—guarantees access to the general curriculum.

In the following sections, we describe the principles, guidelines, and checkpoints and provide examples to demonstrate how the principles can guide the development and implementation of inquiry-based science curricula. We start with the principle of providing multiple means of representation (Principle I), followed by the principle of multiple means of action and expression (Principle II), and lastly move on to multiple means of engagement (Principle III). Table 2.1 provides an overview of the UDL guidelines; however, the complete and expandable version of the UDL guidelines, along with many additional resources, can be found on the National Center for UDL website.

Figure 2.1. The Basic Structure of the UDL Framework