NSTA Reports

Learning STEM by Building Airplanes

By Debra Shapiro

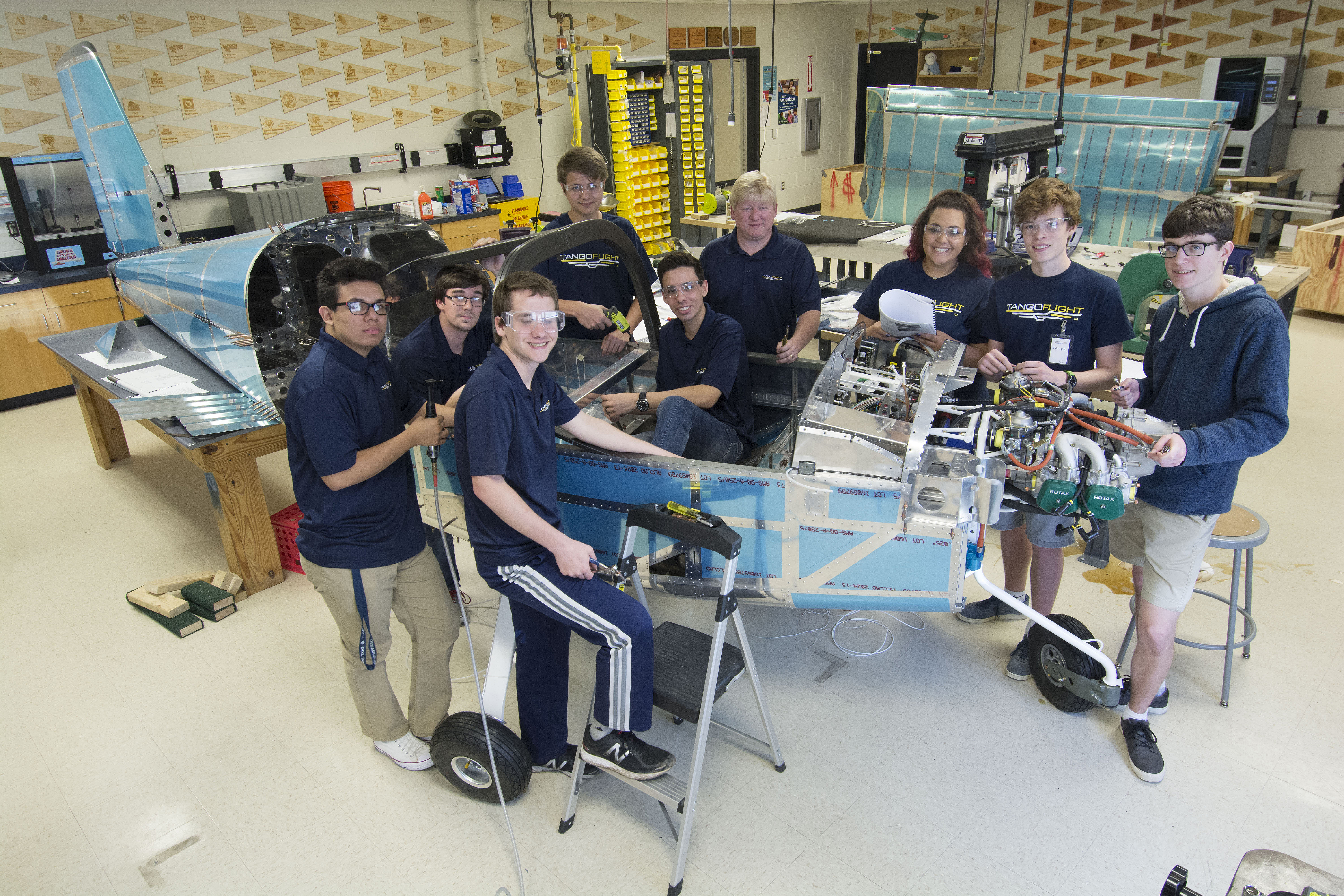

Organizations around the country are helping students and teachers experience the challenges and rewards of building a full-size airplane, allowing students to apply science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) as well. One organization, Texas nonprofit Tango Flight, builds airplanes with students at high schools nationwide. President and co-founder Dan Weyant, Career and Technical Education (CTE) teacher at East View High School in Georgetown, Texas, says the worldwide “demand for pilots, aerospace engineers, and mechanics” inspired him in 2016 to ask his principal and district superintendent if he could establish a year-long class to build a Van’s Aircraft RV-12 two-seat, single-engine, lowwing airplane with students at East View and Georgetown High Schools. Weyant chose the RV-12, which is built from a kit, making it relatively easy to construct compared to other aircraft.

Weyant successfully addressed administrators’ concerns, such as liability. “To mitigate liability, Tango Flight owns the planes and manages assets,” he explains. When a school or district completes a plane, Tango Flight sells it, and the money goes back to the local program to fund the next plane build.

It costs about $100,000 to start the program, he adds, but “there are many ways to fundraise this; the district doesn’t have to pay it all upfront.” Aircraft manufacturer Airbus Americas has funded builds, as well as local aviation museums, businesses, and the city government. Local businesses and nearby colleges and universities also provide mentors for the students.

The first Tango Flight class was a partnership among the two schools, Tango Flight, local businesses, and the STEM program Project Lead the Way (PLTW), on which the curriculum was based. Since then, Weyant, university partners, and Airbus Americas have created a college-level Tango Flight curriculum now used by participating high schools. Tango Flight operates in eight schools in Georgetown, Texas; Wichita, Kansas; Mobile, Alabama; Naples, Florida; Manchester, New Hampshire; Atlanta, Georgia; and Yuba City, California.

“We provide curriculum, training [for teachers and mentors], technical support, and instruments,” Weyant relates. Some Tango Flight schools have students do internships with local businesses, he notes.

Mike Tinich was a PLTW aerospace engineering teacher at Maize South High School in Wichita, Kansas, when contacts at Wichita State University (WSU) recommended him to funder Airbus Americas to do a Tango Flight build. “We built our first plane while [the Georgetown, Texas, group] built their second one…We had a lot to learn, but we had the benefit of their knowledge from their first build,” he recalls.

“We had Airbus engineers work with us as mentors,” and WSU Tech, the local technical college, provided “an experienced airframe [plane structure] instructor to help teach procedures and inspect the finished product,” Tinich reports.

“We were still teaching PLTW during the build, but [Tango Flight] was [the] lab activity. Trying to incorporate both was a challenge,” he admits. “Sometimes the plane took precedence because we had to make sure the plane was safe to fly. ”

Having enough space to build a plane was a dilemma. “The logistics of doing it in a normal classroom were crazy,” Tinich contends. Besides needing room to work, they had “to organize thousands of parts.” Fortunately, “in January 2017, [our school] opened a Career and Technical Center, and the new room had a hangar door on it and more space,” he adds.

“We made a lot of mistakes during the first year, even working with engineers,” Tinich recalls. “But the kids could see adults fail, then move on. [They saw that] failure is an option!”

Students most enjoyed “the opportunity to work with an engineer...It opened their eyes up to opportunities in the aerospace industry,” says Tinich. “Building a plane taught them so much more than just the knowledge of why we have to measure twice and cut once. There was a lot of problem-solving [experience] that was invaluable.”

Aerospace Enrichment

In the Wings Aerospace Pathways (WAP) program held by Wings Over the Rockies Air & Space Museum in Denver, Colorado, students “build and fly drones; earn [Commercial Drone Pilot Certification];...take concurrent enrollment courses toward an A&P [Airframe and Powerplant (engine system)] certification;...and build the RV-12,” says April Lanotte, the museum’s director of education. Designed for students in grades 6–12, WAP is an enrichment program for homeschooled students, those in online schools, and students in traditional schools that allow them to be released one day each week to participate.

Middle school students learn skills to prepare them to build a plane as high school students: using tools, soldering, and learning about basic electronics, ham radios, and aviation and space history, for example. “It helps middle school students decide what’s next for them,” whether they’d like to be pilots, mechanics, or work in another position in the industry, Lanotte maintains.

When choosing students for the build, CTE Coordinator/Instructor David Yuskewich says, “I look for students who are on-task, good at following directions, self-directed, focused, know what tools to use, and are able to lead other students.” In WAP’s tools and skills classes, “parts of the plane that are not done right have to be scrapped, which costs money and time. I don’t accept any less than perfect on the plane,” he asserts.

“During the build, the students do 80% of the work. A group of adults come in on Saturdays and do the rest of the work to keep things on track,” Yuskewich explains.

Students “wear safety glasses, ear protection, aprons, and gloves, so no one gets hurt,” he reports.

“We have a low mentor-to-student ratio so no student works alone,” Lanotte adds. “Students must be technically and mentally able to do the work for safety reasons. They take it seriously.”

Volunteers who have worked in the industry serve as mentors, including inspectors who can certify the work. “I am an EAA Technical Advisor and inspect the planes. We also have a volunteer who is a technical advisor and serves as ‘outside eyes’ when inspecting the planes,” says Yuskevich.

“We [also] have a team of students who are working on restorations of old planes,” reports Lanotte. “These planes won’t be flown again, but students are copying and 3-D printing parts that aren’t available anymore.”

Though WAP’s annual tuition is $1,000, “we do have scholarships, so no one is turned away,” assures Lanotte. “We work with a local school district with a high [number of low-income students]; they receive 100% funding.” Many students, she adds, “earn elective credits” by taking the WAP classes.