Changing schools

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2016-07-31

I’m moving to a different state to take a teaching position. I don’t know anyone there, so where can I look for guidance on state standards and other resources that would be helpful in my new job? —W., Pennsylvania

I’m moving to a different state to take a teaching position. I don’t know anyone there, so where can I look for guidance on state standards and other resources that would be helpful in my new job? —W., Pennsylvania

Congratulations on finding a job! I hope you will have a mentor and meet other colleagues who will help you adjust to a new school in a new state. In the meantime, I suggest the following:

- Be sure to check out your new state’s Department of Education website for links to standards, resources, and professional certification requirements.

- Familiarize yourself with your new school district’s science curriculum guide and the school handbook, and ask about the textbook or electronic resources used in the course and the type of technology available in your school. Browse the websites for your new school and the community.

- To connect directly with others in your new state, subscribe to the relevant NSTA email list and post your state-specific questions or requests for information. There are options by subject areas (chemistry, physics, biology, Earth science, general science), grade level teaching (e.g., elementary, middle, early childhood) or other topics such as Next Generation Science Standards, STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), and pedagogy. In my experience, our colleagues respond with relevant and helpful advice in a timely manner. As an NSTA member, you can subscribe to as many lists as you want through the NSTA website.

- Post questions or requests to NSTA’s Discussion Forums. You can also search previous posts.

- Connect with (and join) the NSTA state chapter or associated group. These local organizations sponsor conferences and other events, post links to professional development opportunities, provide a calendar of events, and offer other ways to connect with science teachers, including social media.

- Check out local science centers, parks, or museums in your new community for what they have to offer. By becoming a member you can connect with other teachers at events, as well as add to a network of community resources. For example, a member of a park that I belong to is a herpetologist and museum curator who is always eager to share his knowledge and expertise.

- When you get to your new community, visit the nearest public library to see what materials and resources are available to you and your students.

- Take a look at what local colleges or universities have to offer, in terms of outreach projects with schools, graduate courses, lecture series, or guest speakers.

Many of these resources can be explored online. If possible, reserve some time before the first day to give yourself onsite opportunities to prepare yourself and your classroom/lab (and have a little breathing room before the first day). During this time, your district may offer teacher workshops. Take advantage of these to meet other teachers and become familiar with the culture of your new school.

Photo: http://www.flickr.com/photos/jjlook/7152722/sizes/s/in/photostream/

I’m moving to a different state to take a teaching position. I don’t know anyone there, so where can I look for guidance on state standards and other resources that would be helpful in my new job? —W., Pennsylvania

I’m moving to a different state to take a teaching position. I don’t know anyone there, so where can I look for guidance on state standards and other resources that would be helpful in my new job? —W., Pennsylvania

Congratulations on finding a job! I hope you will have a mentor and meet other colleagues who will help you adjust to a new school in a new state. In the meantime, I suggest the following:

The Anatomy of the STEM Pipeline: Dissecting Misconceptions at the 2016 #STEMforum

By Lauren Jonas, NSTA Assistant Executive Director

Posted on 2016-07-30

Anatomy: The subject tend to make teachers freeze up, or make the obligatory “gross” puns. But it’s a great topic for STEM, and a career field more students need to know about.

The NSTA staff had a chance to sit down at the 2016 STEM Forum and Expo with Shawn Boynes (SB), Executive Director of the American Association of Anatomists (AAA), and Lisa Lee (LL), Associate Professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, to learn a little more.

Q. What does an anatomy career look like?

A. Anatomy is the core competency for any career in health care. But it’s not just gross anatomy—there are so many branches like histology, neurology, embryology. Career pathways could take students into pathology labs, the field as an anthropologist, a classroom as a biology teacher, the coroner’s office. —LL

Q. What could a K-12 teacher do to encourage more students to go into anatomy?

A. We have members in almost every medical and dental school in the United States, and they work on outreach. Teachers could contact us to find an anatomist who could set up a demonstration or program for them. Going through AAA makes it much easier to develop this type of relationship; you don’t want to just call a med school and ask the receptionist to send a skeleton to your school! —SB

Q. That sounds great for older students, but what about teachers of really young children? Many teachers of that age group don’t have a science background.

A. It doesn’t have to be intimidating. That’s one of our goals is to dispel that notion. A preschool teacher could start with simply getting students familiar with their own bodies. Ask questions like: What are these hard things in here? What’s the squishy part in the middle? What’s this leathery stuff on the outside? And read books about the body with them! —LL

Q. Dissection. It’s a difficult subject for some.

A. There are some stand-ins for biological specimens, but you certainly can’t be a doctor without having dissected an actual human body. But there are some good companies out there, making virtual dissection software, specimens in clay, and so forth. For K-12 students, these alternatives allow students to become familiar with anatomy. —SB

A. At med schools, there is a tremendous respect for cadavers. When we have finished learning from each one, we hold a memorial service and all students and teachers who have been honored to work with it take part, and the family members are invited. The families always come, and it’s very moving. —LL

Q. What do you hope to get out of the STEM Forum and Expo?

A. We are here to learn. We’re in an exploratory phase, for AAA, looking for ways we can reach out to K-12 STEM educators. To learn how we can get student into the anatomy career pipeline earlier, make anatomy more accessible as a subject they can teach. —SB

Q. What else should STEM teachers know about your association?

A. We want to encourage more students to get into the anatomy profession, and we have great programs for preservice anatomy students. Find them all here: Student, Postdoc and Young Faculty Competition Award Winners. We have a strong commitment to bringing younger members into the profession, and in fact we have two Board of Director positions specifically for student members so that they can bring new ideas and help us address their particular challenges. Learn more about us at http://www.anatomy.org/. —SB

Q. Any skeletons in your closets?

A. Yes! I’m a collector, and they come in really handy at Halloween. —LL

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2016 Area Conferences

2017 National Conference

Follow NSTA

Health Wise: Countering Poverty’s Effects on Learning

By Guest Blogger

Posted on 2016-07-30

Poverty is a student health problem, according to the 64,000-member American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP; 2016a).

The AAP announced earlier this year that at all checkups, pediatricians should ask parents and guardians: “Do you have difficulty making ends meet at the end of the month?” This question helps identify the one in five U.S. children who are living in poverty, or an income level at or below $24,230 for a family of four, according to 2015 U.S. Census Bureau data (2016). The number of poor children younger than 18 rises to 43%, or 31.5 million, when families designated as “poor,” “near poor,” and “low-income” are included in census data, according to the AAP (2016a).

“Research shows that living in deep and persistent poverty can cause severe, lifelong health problems, including … poor language development, higher rates of asthma, and obesity. A growing body of research links child poverty with toxic stress that can alter gene expression and brain function and contributes to chronic cardiovascular, immune, and psychiatric disorders, as well as behavioral difficulties” (AAP 2016a).

“While urban and rural areas continue to have high rates of poverty, the suburbs have experienced the largest and fastest increases in poverty since the 2008 recession,” the AAP says. “Poverty is everywhere. It affects children of all backgrounds and in all communities,” says AAP president Benard P. Dreyer (AAP 2016a).

Moreover, the consequences of poverty can limit educational achievement, the AAP says (2016b). Irwin Redlener, a professor of pediatrics at Columbia University, also wrote about the role poverty plays in education achievement in an Education Week commentary:

“Kids are sleeping at their desks after being up all night wheezing with untreated asthma. They are failing tests because they don’t have the glasses they need to read a lesson on the blackboard. They are being held back a grade because they can’t hear the teacher. They are acting out because they are traumatized by extreme stress in their home. These are the health burdens of poverty that weigh on children in classrooms every day” (Redlener 2014).

One study found that half of parents of uninsured children were unaware that their children were eligible for government health insurance. The study of 267 uninsured children in Texas found that 38% had health problems, 66% had special healthcare needs, and 64% had no primary care provider, although their parents or guardians were eligible for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (Flores et al. 2015).

“High school science teachers who believe poverty may be affecting their students’ health can talk with the principal, school nurse, or school counselor,” says Dr. Mary Lou Gavin, senior medical editor for KidsHealth.org. “Make sure low-income students are benefiting from school services, such as counseling and free or reduced-price breakfasts and lunches. Educators also can refer families to local, state, and federal resources that offer help with food, housing, heat, clothes, and health insurance.”

Michael E. Bratsis is senior editor for Kids Health in the Classroom. E-mail him with comments, questions, or suggestions.

On the web

For students:

Coping with stress articles, in English and Spanish: http://bit.ly/1T79DIf

For educators:

Poverty in schools: http://edut.to/1Mrni7P

At-Risk School Success Stories: http://bit.ly/1RWIFE5

How Being Poor Makes You Sick: http://theatln.tc/1vGeoxh

School breakfast, school lunch, and supplemental nutrition assistance programs: http://1.usa.gov/1AGZ71S, http://1.usa.gov/N9l7Oj, http://1.usa.gov/1gLikau

References

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). 2016a. American Academy of Pediatrics recommends pediatricians screen for poverty at check-ups and help eliminate its toxic health effects. http://bit.ly/1p8ykcP

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). 2016b. Poverty and child health in the United States. http://bit.ly/1RTcWiY

Flores, G., L. Hua, C. Walker, M. Lee, A. Portillo, M. Henry, M. Fierro, and K. Massey. 2016. A cross-sectional study of parental awareness of and reasons for lack of health insurance among minority children, and the impact on health, access to care, and unmet needs. International Journal for Equity in Health 15 (44). http://bit.ly/1Zps9y0

Redlener, I. Education Week. 2014. A Healthy Child Is a Better Student. August 5. http://bit.ly/XpBJqu

U.S. Census Bureau. 2016. Poverty. http://1.usa.gov/1z7zD9Z

This article was originally published in the Summer 2016 issue of The Science Teacher journal from the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA).

Get Involved With NSTA!

Join NSTA today and receive The Science Teacher, the peer-reviewed journal just for high school teachers; to write for the journal, see our Author Guidelines and Call for Papers; connect on the high school level science teaching list (members can sign up on the list server); or consider joining your peers at future NSTA conferences.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2016 Area Conferences

2017 Nati

onal Conference

Follow NSTA

Manipulating Contents & Containers, and representing 3-D objects in block play

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2016-07-29

It is so fascinating how obvious it is that children have different prior experiences, different developmental ages, and different interests when we teachers present them with a set of materials and don’t ask them to use them in a particular way! This post is a reflection on how two different sets of objects are used by preschool children ages 3-5 years. The experiences I describe are just the beginning of explorations into the relationship between “contents” and “containers,” and the way 2-D materials can represent 3-D structures.

Contents and containers

I had the pleasure of working with two classrooms on building with a variety of materials, a class of young-to-old three-year-olds and a mixed age classroom of just-four-year-olds to older five-year-olds. We teachers provided a set of “contents and containers” to both classes, inspired by presentations by Dr. Rosemary Geiken and Dr. Jill Uhlenberg (Geiken 2009).

I had the pleasure of working with two classrooms on building with a variety of materials, a class of young-to-old three-year-olds and a mixed age classroom of just-four-year-olds to older five-year-olds. We teachers provided a set of “contents and containers” to both classes, inspired by presentations by Dr. Rosemary Geiken and Dr. Jill Uhlenberg (Geiken 2009).

The contents we used were balls of different sizes, film canisters, cotton balls, and lids from various jars and bottles. The containers were made-for-food-storage plastic tubs, recyclable oatmeal/coffee canisters and cans, plastic netting from fruit, plastic cups, and sections of drainage tubes. I chose these objects because they were easy to access and could fit together in more than one way. Our purpose was to observe the children to understand more about what interests them and their approach to new materials.

In both classrooms there was a variety of approaches: some children collected as many of the “contents” as they were able to, many explored the way the contents fit into the various containers and how the containers could open and close, some tried making a system to move the contents into and between the containers, and others used the objects to make sounds or as part of imaginative play. They encountered problems to struggle with and sometimes solve: there wasn’t enough room in the container for all the collected contents, an object got stuck inside a container, two containers got stuck together, and there weren’t enough of the coveted objects to satisfy all who wanted them.

In both classrooms there was a variety of approaches: some children collected as many of the “contents” as they were able to, many explored the way the contents fit into the various containers and how the containers could open and close, some tried making a system to move the contents into and between the containers, and others used the objects to make sounds or as part of imaginative play. They encountered problems to struggle with and sometimes solve: there wasn’t enough room in the container for all the collected contents, an object got stuck inside a container, two containers got stuck together, and there weren’t enough of the coveted objects to satisfy all who wanted them.

We could see which children needed support to persist, and were able to use open-ended prompts (statements from teachers) to support children in trying alternative solutions. Over the weeks of using the materials the children began using them with other classroom materials, finding new purposes for both contents and containers, and new problems to solve. Beginning with a set of materials that could be used in many ways allowed us to really see what developed, because we didn’t have an expectation of how the children should use them. The play that sprang forth reminded me of the play that happens in workshops by Dr. Walter Drew (see video examples) and his work with co-authors Dr. Marcia Nell and Dr. Baji Rankin.

Using 2-D shapes to represent 3-D structures

When we do ask children to use materials in a particular way, their different prior experiences, different developmental ages, and different interests also become apparent. We can use this information to guide our lesson planning and discussions about children’s work.

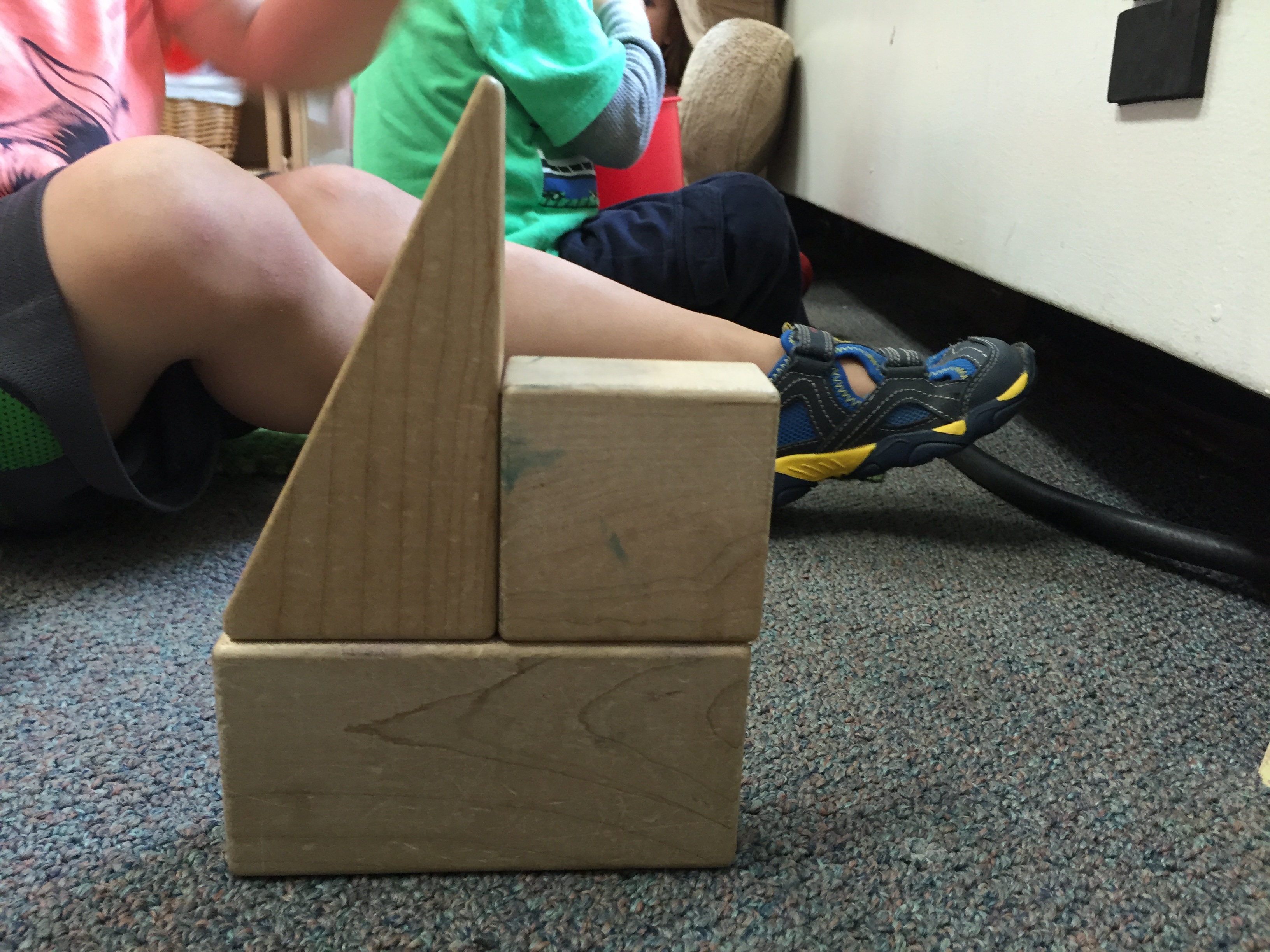

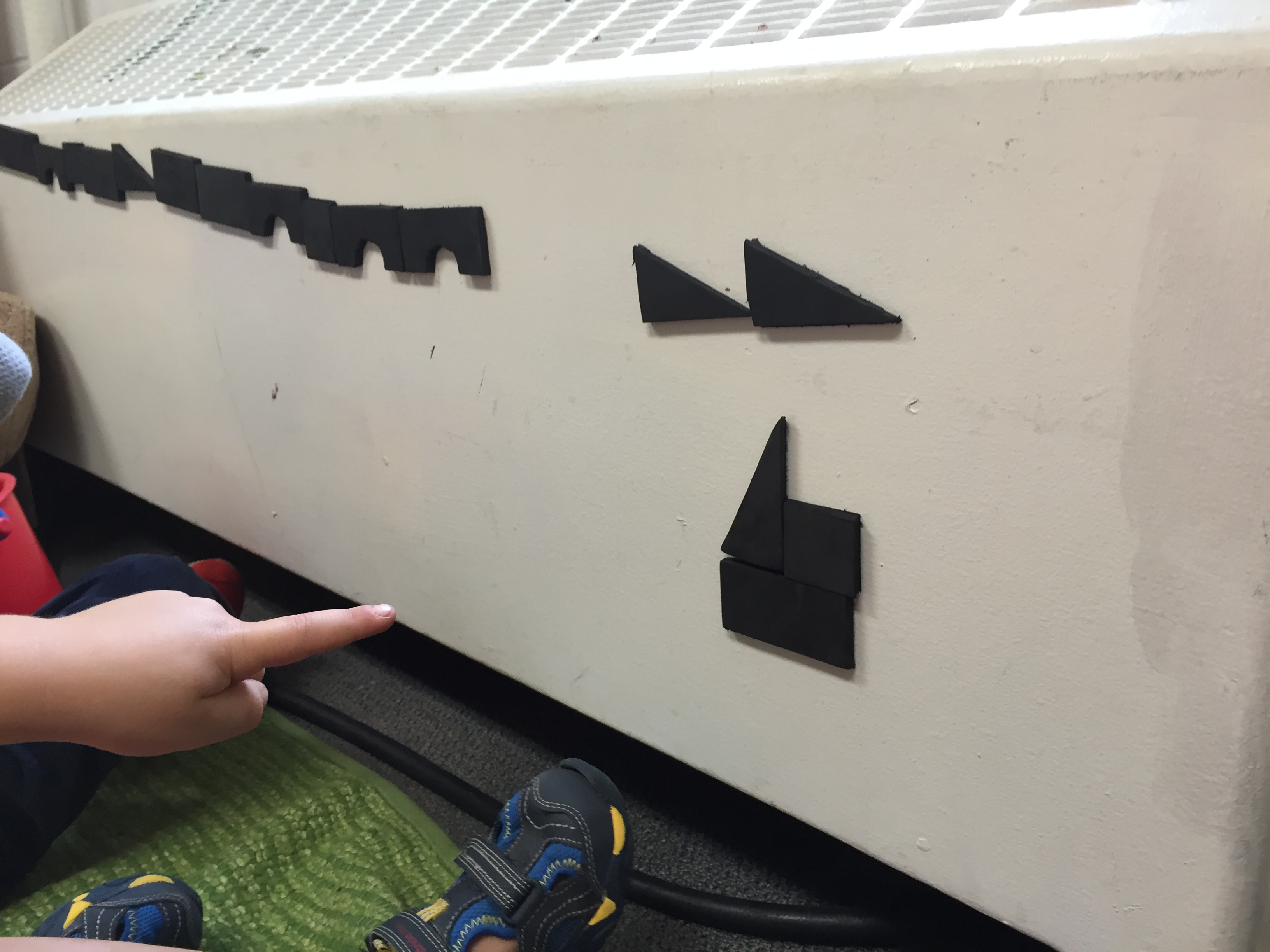

A teacher shared her previous experience of making the 3-D unit block shape cross-sections in the medium of 2-D art foam with magnetic backing to be used on a radiator or white board. We made a set based on the blocks available in the classrooms and asked children to build with a small set of blocks and then represent their structure using the 2-D art foam blocks. We hope that children will later use the foam blocks to represent the 3-D structures they want to save and reflect on after the 3-D blocks are put away.

This was a new material for most of the children so we expected them to be mostly interested in using the art foam block shapes. A few children in both age groups created small wooden unit block shapes and then used the 2-D art foam shapes to represent the structure.

They looked back and forth between their unit block structure and their art foam block representation on the wall. A child who was trying to make a symmetrical structure with a triangle block on either side of a central rectangular block was frustrated by the lack of triangle blocks that faced both ways. It quickly became apparent that I had only made “right-handed” triangle blocks, sticking the magnetic backing to the triangles when they were all facing the same way! Luckily I had additional material and could correct this omission. But the situation allowed us to assess that the child was very aware of the direction of her triangle block.

They looked back and forth between their unit block structure and their art foam block representation on the wall. A child who was trying to make a symmetrical structure with a triangle block on either side of a central rectangular block was frustrated by the lack of triangle blocks that faced both ways. It quickly became apparent that I had only made “right-handed” triangle blocks, sticking the magnetic backing to the triangles when they were all facing the same way! Luckily I had additional material and could correct this omission. But the situation allowed us to assess that the child was very aware of the direction of her triangle block.

Some children began building a long “train” of the 2-D art foam blocks and others wanted to see how many of the art foam blocks it took to cover a set of unit blocks lying on the floor. The idea of representing a 3-D block structure may become important another day if they want to save a particular structure to use the following day but space requirements don’t allow structures to stay up during nap time. A 2-D representation can help children remember what blocks they used so they can recreate the structure and perhaps redesign it.

Some children began building a long “train” of the 2-D art foam blocks and others wanted to see how many of the art foam blocks it took to cover a set of unit blocks lying on the floor. The idea of representing a 3-D block structure may become important another day if they want to save a particular structure to use the following day but space requirements don’t allow structures to stay up during nap time. A 2-D representation can help children remember what blocks they used so they can recreate the structure and perhaps redesign it.

It will be interesting to see if using the 2-D foam block shapes has any influence on whether childr

en choose to draw their 3-D wooden block structures on paper, and how easy it is for them to document and represent their structures in yet another medium.

Geiken, R., Uhlenberg, J., Uhlenberg, D, & York, C. (November 2009). Toddlers engaged in inquiry and problem solving: Promoting learning in science and math with spheres and cylinders. National Association for the Education of Young Children National Conference, Washington, DC Conference session

Drew, Walter F. and Baji Rankin. 2004. Promoting Creativity for Life Using Open-Ended Materials. Young Children July 2004

Nell, Marcia L., and Walter F. Drew, With Deborah E. Bush. 2013. From Play to Practice: Connecting Teachers’ Play to Children’s Learning. NAEYC

It is so fascinating how obvious it is that children have different prior experiences, different developmental ages, and different interests when we teachers present them with a set of materials and don’t ask them to use them in a particular way! This post is a reflection on how two different sets of objects are used by preschool children ages 3-5 years. The experiences I describe are just the beginning of explorations into the relationship between “contents” and “containers,” and the way 2-D materials can represent 3-D structures.

Contents and containers