Nature experiences and empathy—see the March issues of journals for early childhood educators

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2012-03-22

Both the NSTA journal Science and Children, and the NAEYC journal Young Children, were especially riveting this month, March of 2012. I quickly look through the journals to get a feel for the issue, and then put them in my reading bag or pile, unless I happen to be sitting down to the rare quiet meal by myself—then I begin to read from cover to cover. This month I’ve read them little by little and here are a few thoughts. Please get these journals and read them yourselves, and then comment below to share your thoughts.

Both the NSTA journal Science and Children, and the NAEYC journal Young Children, were especially riveting this month, March of 2012. I quickly look through the journals to get a feel for the issue, and then put them in my reading bag or pile, unless I happen to be sitting down to the rare quiet meal by myself—then I begin to read from cover to cover. This month I’ve read them little by little and here are a few thoughts. Please get these journals and read them yourselves, and then comment below to share your thoughts.

In the Early Years column I suggest that a water source such as a birdbath can attract animals close enough to the school to observe, and collect data by drawing. On a walking fieldtrip today just around the playground and school building my preschoolers saw many signs of spring, including flowering paw-paw and Bradford pear trees, forsythia flowers, Cabbage White butterflies, and a starling carrying pine needles from the big tree up to a hole in a pipe to build a nest. Nature is waiting for us just outside the door.

The Bradford pear trees in my community are in full bloom this week—beautiful when in a still picture and on a still afternoon but troublesome in the real world, especially on a windy day or in a heavy snowfall when their limbs are likely to break, or when they spread into a wild natural area. Read about how teachers developed the role-play to engage fifth-grade students in understanding scientific inquiry, ecosystems, diversity, and risks and benefits in Banishing Bradford Pears by Cynthia Deaton and Michelle Cook. Then think of an environmental problem that is within the control of your younger students, and role-play on how to effect change. The problems that preschool age children can fix are ones we are familiar with: the sandbox is almost empty because the sand has been carried to other parts of the school yard, a classroom toy is missing parts because they were not put away when last used, the paper towel dispenser has run out because people are using two and three towels when one would be enough, or the plants in the garden are wilted because no one has watered them.

The Bradford pear trees in my community are in full bloom this week—beautiful when in a still picture and on a still afternoon but troublesome in the real world, especially on a windy day or in a heavy snowfall when their limbs are likely to break, or when they spread into a wild natural area. Read about how teachers developed the role-play to engage fifth-grade students in understanding scientific inquiry, ecosystems, diversity, and risks and benefits in Banishing Bradford Pears by Cynthia Deaton and Michelle Cook. Then think of an environmental problem that is within the control of your younger students, and role-play on how to effect change. The problems that preschool age children can fix are ones we are familiar with: the sandbox is almost empty because the sand has been carried to other parts of the school yard, a classroom toy is missing parts because they were not put away when last used, the paper towel dispenser has run out because people are using two and three towels when one would be enough, or the plants in the garden are wilted because no one has watered them.

Establishing the habit of stewardship, or taking care of the environment, can start before appreciation of why this is important takes root. Even though we model good manners and environmental stewardship, our students may not copy our behavior so we can provide experiences that highlight how important these behaviors are. There will always be a range of expression of empathy in a class but by requiring “pleases” and “thank-yous” we set expectations for children as they grow. When “we all clean up to make our classroom a pleasing place” is a community expectation, it becomes a habit that we hope will carry over into the larger world. (Do you have a favorite clean-up song or signal for your classroom?)

I agree with what David Sobel says in his 2008 Focus the Nation presentation at Antioch University, Global Climate Change Meets Ecophobia. He said, “My desire is to approach this from a perspective that maximizes hope. If we lead with all the tragic implications of climate change, then we risk scaring children into despair. In Beyond Ecophobia I suggested, ‘No (environmental) tragedies before fourth grade.’” You can watch this presentation online at http://old.antiochne.edu/focusthenation/ecophobia_sobel.cfm

What will make children become environmental stewards? I think that the caring community described in the Young Children article, “One Mommy Breast and One Daddy Breast: Encountering Illness as Emergent Curriculum” is what will help young children develop a sense of responsibility for others and develop their ability to take action. In the article, a teacher who was diagnosed with breast cancer said this about how she would tell the children she worked with about her illness and the treatment process she would be going through. “…We have dealt with difficult topics before—a knee surgery, and the death of a family pet. I believe children are capable, ready to engage, to learn. Gandini’s quote on the image of children is the one I hold on to:

All children have preparedness, potential, curiosity, and interest in constructing their learning; in engaging in social interactions and negotiating everything that the environment brings them. (Gandini, L. 1993. “The Fundamentals of the Reggio Emilia Approach to Early Childhood Education,” Young Children 49 (1): 4-8)

If you believe this, it’s a no-brainer that cancer is an illness that would be discussed, documented, researched, and experienced in the classroom.”

The teacher did not exclude the children from taking the journey with her but she did not begin by describing the seriousness of her illness. The children responded with actions which were within their power—with matter-of-fact questions and discussion, making hats and hair for the teacher and wearing headscarves until they were able to accept her baldness caused by chemotherapy. This teacher and the other authors ask, “Does it protect the children to keep them apart from it [knowledge of serious illness]? Or does it isolate and remove children’s power to act?” They also said “It is not that adults would ask the children to do so [take on the responsibility of supporting an ill teacher], but that their empathy and care contributed in an essential way to the healing of others.”

Sobel reports that involvement with local nature experiences is strongly tied to environmental stewardship. The March 2012 issue of Science and Children focuses on ways to get teachers and students outside to have those direct experiences with nature. By supporting children’s development of empathy and their ability to act, as shown in the Young Children article, and providing direct experiences as part of the local nature, teachers can foster children’s love of the environment and stewardship actions appropriate to their age and ability.

Sobel reports that involvement with local nature experiences is strongly tied to environmental stewardship. The March 2012 issue of Science and Children focuses on ways to get teachers and students outside to have those direct experiences with nature. By supporting children’s development of empathy and their ability to act, as shown in the Young Children article, and providing direct experiences as part of the local nature, teachers can foster children’s love of the environment and stewardship actions appropriate to their age and ability.

Peggy

Both the NSTA journal Science and Children, and the NAEYC journal

Both the NSTA journal Science and Children, and the NAEYC journal

Earth Day

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2012-03-21

A lot has changed since the first Earth Day, especially in the area of technology and the emphasis on test results. The More High-Tech Our Schools Become, the More They Need Nature sets the stage for the rest of this issue with Richard Low’s call for both formal and informal learning activities for “no child left inside.”

Do Earth Day activities have a life beyond the designated day? The authors of Green Team to the Rescue state that “The environmental science opportunities we offered were one-shot lessons sprinkled throughout science units; they were not connected across grade levels and rarely tied to the world outside the classroom.” So they transformed an afterschool club into a service learning opportunity that helped students develop leadership skills in environmental science. They provide descriptions of some of their students’ projects.

Sweetgrass Science focused on place-based education and making classroom content more meaningful to students by connecting science content to the lives of the students through local issues, culture, and people. Although the project was based in South Carolina, it’s certainly possible to replicate this interdisciplinary study anywhere. Get ‘Em Outside is another example of place-based education–in this case students turning an abandoned lot into a nature study center for activities such as the identification ones described in The Naming Convention. [SciLinks: Taxonomy]

Banishing Bradford Pears has suggestions for an activity in which students investigate a topic (in this case, an introduced species of ornamental tree) from several points of view and share their findings via role-playing. [SciLinks: Invasive Species] Speaking of trees, although buds are bursting early this spring, students may ask Why Do Leaves Fall Off Trees in the Fall? This explanation is an easy read that can be shared with students. [SciLinks: Plant Tropisms, Identifying Trees, Autumn Leaves, Leaf Structure and Function]

One of the activities associated with Teaching the Three R’s: Reduce, Reuse, Recycle is “Where Does Garbage Go?” The other day I saw one of the answers—a huge landfill in the middle of what was pristine farmland. Speaking which, From Landfills to Robots describes a project in which students explored the recycling process by becoming “Wise About Waste” and involving students and their families in an interdisciplinary study. Many of us take recycling for granted these days, but as I traveled in Europe last year, I saw how recycling becomes a way of life—composting, no disposable water bottles, and people take their own bags into stores (I see more of that here, too). [SciLinks: Recycling]

The internet has changed the notion of “pen pals” with Skype in real time, no stamps to purchase, no writing paper, and no waiting for weeks for a response (although I must admit it was exciting to get an envelope in the mail). The project described in Birds Across Borders connected students in the US and Scotland in a citizen science collaboration. To the list of resources at the end, I’d add Bird Studies Canada. Learning by Nature and Save the Boulders Beach Penguins include suggestions for getting young children involved in studying birds and their needs. [SciLinks: Birds, Bird Adaptations]

And check out more Connections for this issue (March 2012). Even if the article does not quite fit with your lesson agenda, there are ideas for handouts, background information sheets, data sheets, rubrics, and other resources.

ChronoZoom: A real OMG moment in time!

By Martin Horejsi

Posted on 2012-03-19

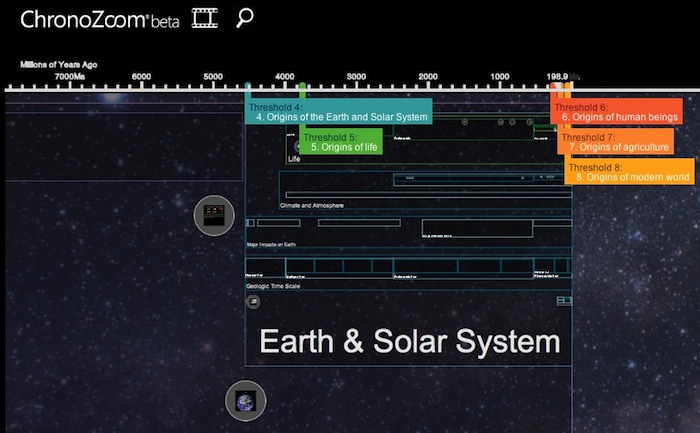

What would happen if you could dive in and out of any particular moment of time within a brilliantly conceived visual interface that marries Prezi with the universe? Well, I’m not sure, but I bet it would look something like ChronoZoom.

I know it sounds silly or cliché but ChronoZoom (www.ChronoZoomproject.org) is really jaw dropping! ChronoZoom takes a 13.7 billion year timeline and makes it fast, easy, and intuitive to move through the history of the universe (or the earth, or humanity, or the industrial revolution) at whatever scale and speed you like. One moment you are at the beginnings of chemical complexity, the next you are the origins of agriculture.

For many of the “thresholds” there are resources that can be zoomed into providing images, text, and movies.

ChronoZoom was funded by Microsoft Research Connections in collaboration with University California at Berkeley and Moscow State University (the one in Russia, not Idaho) Although it is still mostly empty space, that is something that will change rapidly as it gains traction across the curriculum.

As a free tool, ChronoZoom runs in a web browser like most other websites except the experience is dramatically more interactive. The project is built on HTML 5 coding that allows it to run on almost any modern web browsing device, and movement around the timeline is smooth, fairly seamless, and best of all in my opinion is that it takes advantage of gesture-input devices giving it a much more natural flow then possible by a mouse alone.

According to the website, “ChronoZoom is an open source community project dedicated to visualizing the history of everything to bridge the gap between the humanities and sciences using the story of Big History to easily understand all this information.”

When zoomed into a topic or “threshold,” the available media presents itself and can be further zoomed into for consumption.

ChronoZoom reeks with potential including the suggested possibilities listed on the site such as:

- Ability to create my personal canvas/timeline/tours

- Ability to generate internal user bookmarks

- Generate a chart dynamically and place it where I want on the timeline

- Display curve and segmented line graphs, plot of events coded for magnitude

- Phylogenetic trees

- Svg drawing

- Filter Exhibits based on subject

- Choose data from data library

- Customize time direction up and down, down to up, left to right, right to left

- Comparison of timeline, Comparison of data, Comparison of data and timelines

- Ability to share my timeline or tour with others via social networking

- Ability to show uncertainty of dates (+/-)

- Ability to show a time range and not only just a specific date in time

- Ability to show multiple interpretations

- Ability to show geo-spacial data

While the traditional applications of ChronoZoom in the classroom are many, it will be the as-yet unimagined uses that will rock education. So take ChronoZoom for a ride and post your travel adventures here.

What would happen if you could dive in and out of any particular moment of time within a brilliantly conceived visual interface that marries Prezi with the universe? Well, I’m not sure, but I bet it would look something like ChronoZoom.

Thinking about homework

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2012-03-15

The teachers on our team all have different homework policies which confuses our students and their parents. Do you have any suggestions to help us become more consistent?

The teachers on our team all have different homework policies which confuses our students and their parents. Do you have any suggestions to help us become more consistent?

–Jacob from Virginia

My views on homework evolved throughout my years in the classroom, as I came to understand my students better and improve my instructional strategies. Rather than suggestions, I’ll offer some reflections to stimulate discussion with your colleagues. I suggest, however, that you examine some of the research on the effectiveness of homework (for example, the book Rethinking Homework has a chapter on this topic). I’ve created a resource collection with summaries of research studies and other readings.

Perception of homework’s value is mixed. Teachers who don’t assign homework are considered “easy,” regardless of what their in-class expectations. Teachers who give a lot are “rigorous,” even if the assignments are trivial, unnecessary, or unrelated to the learning goals. Some parents demand homework for their children, others make excuses or even do the assignments for the student. Some schools have formulas as to how much homework is appropriate (X minutes multiplied by the grade level), homework hotlines, and homework sessions at the end of a marking period for students to recoup some points toward their grades.

I once had lunch with teachers at an elementary school where their discussion centered on consequences for students who didn’t complete homework. The options included keeping students after school, reducing their grades, keeping them in at recess, calling parents, issuing demerits, or giving “gotcha” quizzes. They also discussed whether to accept late assignments. But not one teacher mentioned the value or purpose of the assignments.

I observed a class where the “homework” was a find-a-word on the planets (it must have been an oldie—Pluto was still listed as the ninth planet) and a maze “Help the Astronaut Find His Spaceship.” I have no idea what the learning goals were for this busywork, but I suspect that if students did not do these worksheets, they would have suffered the “consequences.”

If a learning activity, such as completing a worksheet or study guide, is completed in class, it’s called classwork, but completed outside of class it’s categorized as homework and weighted differently toward a grade. The same activity is awarded points based on where and when it is to be completed, not on how it helps students with the learning goals. And I’m puzzled by students who claim that they finish all of their homework in class—is the assignment then reconsidered classwork?

I’m concerned when homework used as a punishment: “If you don’t settle down, you’ll have homework this evening.” Or when lack of homework is used as a reward: “You’ve all behaved very well today, so there will be no homework” or “You can earn a ‘get out of homework’ pass for doing Z,” a behavior unrelated to the learning goals.

What about students who don’t have support at home? Do all your students have parents who help or encourage them? Do they have access to technology, a quiet place free from interruptions and distractions, or even something as simple as a box of pencils and paper? How should students juggle homework with other meaningful activities such as music lessons, sports, family events and responsibilities, community activities, afterschool jobs, or personal interests?

What if we gave students ideas for pursuing topics of interest outside of school rather than busywork for its own sake—options such as reading lists, videos, or other science-related activities that engage students without the “grade” component?

However, it might be reasonable to ask students to practice skills, finish a lab report started in class, review the content presented in class, or prepare for a lesson (e.g., videos, podcasts, readings). You might be interested in learning more about the “flipped classroom” model (follow #flipclass on Twitter).

Some suggest homework teaches students to be responsible, but it seems this lesson is not learned very well. Teachers of juniors and seniors still complain about students not doing homework. We should ask what we’re asking students to be responsible for—for making decisions about their learning? Or for complying with the teacher’s directions?

Brian (not his real name), who had a reputation among the seventh grade teachers for not doing homework, gave me a lot to think about one morning when he met me at the door. “Did you see that TV show on spiders last evening?” he asked, referring to a PBS program. He talked nonstop about spiders and mentioned some library books he had read. Obviously something had captured his interest! I wondered what homework did not get done as he pursued his interest in spiders? Were other teachers punishing him for spending time on this rather than on their assignments?

Resource:

Vatterott, C. 2009. Rethinking homework. Alexandria, VA: ASCD

Photograph:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/ms_sarahbgibson/1266617074/

The teachers on our team all have different homework policies which confuses our students and their parents. Do you have any suggestions to help us become more consistent?

The teachers on our team all have different homework policies which confuses our students and their parents. Do you have any suggestions to help us become more consistent?

–Jacob from Virginia

Addressing misconceptions in science

By Claire Reinburg

Posted on 2012-03-15

A significant challenge that science teachers face is how to help students successfully navigate the bridge from their existing ideas about science concepts to scientifically accepted views. A teacher who uncovers students’ preconceptions about key concepts can use that knowledge to provide learning experiences that support students as they develop richer conceptual understanding. The March 2012 issue of NSTA’s Book Beat highlights resources that can help teachers guide their students on the path from misconceptions to clearer understanding. Page Keeley’s Uncovering Student Ideas in Science Series has been a go-to source for many teachers who want to learn more about what students are thinking about gravity, force and motion, cells, life cycles, and numerous other science topics.

This issue of Book Beat links to two free preview chapters from Page Keeley and Cary Sneider’s brand-new Uncovering Student Ideas in Astronomy. What do your students know—or think they know—about what causes night and day, whether the Moon spins, and what happens to stars when they die? The 45 astronomy probes in the new book provide situations that will pique your students’ interest while helping you evaluate their understanding of how the universe operates. The book covers the broad areas of the nature of planet Earth; the Sun-Earth system; modeling the Moon; dynamic solar system; and stars, galaxies, and the universe. Andrew Fraknoi writes in his Foreword to this new book: “Just like a doctor’s diagnostic tool provides one chemical or physical indicator of our health, each of Keeley and Sneider’s probes measures one or two ideas that lets you know how much surgical repair (if any) might be needed to fix up your students’ astronomical ideas.” For additional resources on misconceptions in science, check out the Everyday Science Mysteries Series; Predict, Observe, Explain; and the Brain-Powered Science Series. Additional NSTA Press resources on astronomy include Project Earth Science: Astronomy, Revised 2nd Edition; and Earth Science Success: 50 Lesson Plans for Grades 6–9.

A significant challenge that science teachers face is how to help students successfully navigate the bridge from their existing ideas about science concepts to scientifically accepted views. A teacher who uncovers students’ preconceptions about key concepts can use that knowledge to provide learning experiences that support students as they develop richer conceptual understanding.

Environmental change

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2012-03-14

How does a change in climate affect an environment and the organisms that live in it? This could be an essential question for an ecology or environmental science unit. Students hear a lot about climate change but may not have made the connection between changes in climate and the resulting impact on water quality, landforms, seasonal migrations, or coastlines.

Generating Arguments About Climate Change Argument in this case is not a yelling match as seen on TV or radio talk shows. Question-Response/Explanation-Evidence and Reasoning describes how to guide students through the process with activities, informational resources, [SciLinks: Changes in Climate, Modeling Earth’s Climate]

Explaining Four Earth Science Enigmas with a New Hypothesis describes the “airburst theory of an extraterrestrial object that entered the earth’s atmosphere over North America during the last Ice Age, causing fundamental changes in the Northern Hemisphere.” The article has an example of a jigsaw activity and guiding questions for students to examine several puzzling events. The authors also provide a list of resources, including their own site on the topic. The Sixth Great Mass Extinction outlines the possible causes and the results of five previous extinctions (all of which predate human activity) and discusses the current thinking about a sixth extinction occurring now. The article does not have any lesson plans per se, but the authors provide an extensive list of resources on the topic that can be integrated into many science topics. [SciLinks: Mass Extinctions]

Articles such as these and Reconstructing Environmental Change Using Lake Varves as a Climate Proxy reinforce the idea that earth science should be the capstone course in schools—integrating concepts from the life and physical sciences. This article describes how data (proxies) such as lake sediment layers (the varves of the title), annual tree rings, and ice thickness can be used to reconstruct climate patterns of the past. The authors describe a class investigation into paleoclimatology. [SciLinks: Paleontology]

Talk about a coincidence—just as I started reading Why Did the Bald Eagle Almost Become Extinct, I saw one flying over the wetlands behind my house. What a sight, as it soared over the water and landed in a tall tree, its white head gleaming in the sun. And yet it wasn’t that long ago that their future was in question. Using the activity described in this article (which includes a rubric and examples of “evidence”), students learn about the environmental factors that threatened this the existence of this bird. [SciLinks: Bird Adaptations, Bird Characteristics, Food Chains and Food Webs, Endangered Species]

Living downriver from fracking sites, I was very much interested in the article Fracking Fury. The explanation of the process, the map of shale gas locations, and the diagram of how hydraulic fracturing works are valuable resources for any teacher K-12 and for students. Although natural gas may burn cleaner than other fossil fuels, its extraction poses potentially harmful effects on the local environment.

When you pick up this month’s issue, think of the environment in terms of the outdoors. In the guest editorial Reflections on a Classroom Managed Through Inquiry: Moving Past “Nondiscipline” the author very honestly described how she has changed the classroom environment through the type of interactions with students. Most of us would probably like to meet our first year’s students and explain how we are much better teachers now!

Check out the Connections for this issue (March 2012). Even if the article does not quite fit with your lesson agenda, this resource has ideas for handouts, background information sheets, data sheets, rubrics, etc.

Critical thinking

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2012-03-11

A teacher at a workshop once told me, “I keep my student so busy, they don’t have time to think.” I hope she was joking, because helping students learn how to engage in critical thinking—problem solving, creating, analyzing—and to develop their own strategies for self-evaluation and learning is one of the most important things we do.

Did you ever look at some students’ work and wonder What Were They Thinking? The authors of this article discuss how to design and support learning activities that will help students develop critical thinking skills: connecting to background knowledge, creating sensory images (nonlinguistic representations), determining importance (prioritizing), questioning, inquiry (problem solving, inferring, predicting, synthesizing. They provide sample lessons that teach the big picture and focus on real-world applications.

Even if you don’t have funds for elaborate materials or field trips to exotic locations, you can still Rock On! using samples of local gravel, which can be the basis of activities to foster observation and critical thinking. It was interesting that the activity was also included in a PD workshop, and teachers thought of even more ideas for extending the activity. If you want to see where an interest like this can lead, check out the Science of Sand website. [SciLinks: Rocks, Erosion]

Do we focus so much on getting the “right” answer that we overlook how to analyze our work? Does it make sense? Are You Certain? If your students do many discovery investigations, error analysis is an essential skill, and the author describes several strategies for guiding students through the process. The article includes a helpful graphic on the experimentation in science classrooms.

One aspect of critical thinking is reading between and beyond the lines to determine What’s Missing? The author of this article uses articles from the media (a list is provided) to help students indentify the environmental stories and questions hidden in the articles. She emphasizes the importance of teacher modeling how to think through the process and provides examples and a guide to writing a “thoughtful” response. She also suggests modifying the activity with cooperative learning. And I really liked her idea of using online discussions/forums.

In the classroom, teachers usually focus on what (and how much) students know. But the author of Exploring the Unknown notes that “Scientists get excited about what they don’t know” (the italics are mine). The article describes a project in which students explore real-life investigations into the classroom, not necessarily to find answers but to learn how to think like scientists. There are resources to help student learn to make scientific claims, justify them with evidence, and evaluate the quality of the evidence. (see the SS article for more on argumentation). [Scilinks: Aquifers]

Next month is the celebration of Earth Day 2012. This article has a brief history of the event and a list of web-based resources for related activities. (see the March 2012 issue of Science & Children for more ideas).

Don’t forget to look at the Connections for this issue (March 2012). Even if the article does not quite fit with your lesson agenda, this resource has ideas for handouts, background information sheets, data sheets, rubrics, etc.

Are we in the midst of a STEM movement?

By Francis Eberle

Posted on 2012-03-09

Each day there seems to be more focus and discussion about STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) education. The volume of comments in the various social media forums seems to have really taken off: in the first few hours the other morning I was reading the discussion on one of our blogs about starting a STEM school in China and about the need to better prepare students. An electronic newsletter that came across my desk highlighted new STEM programs, schools and funding in Texas, Massachusetts, Louisiana, Ohio, Arizona, and California.

This is not unusual. In an average week NSTA gets several requests to participate in an event, a forum or a media interview about STEM. The discussion often centers on a specific topic within STEM, such as science education, the introduction of engineering, elementary science, and what, exactly, is a STEM school.

But I’m beginning to wonder: is this just “buzz”—or is it an indication that schools really are focusing more on STEM?

After talking with teachers this past week I don’t think this is true. In far too many local schools, science is still not given adequate time and the amount of instruction time is actually being reduced. Topics in mathematics are generally not a part of the STEM conversations. School resources are still very tight which means acquiring new materials for teaching science is more difficult.

At the federal level Race to the Top funds and Investing in Innovation (I3) projects are supposed to include STEM as a focus. The state Math and Science Partnership funds are supporting STEM projects in every state. There are privately supported STEM school networks in at least 6 states and there are a number of state STEM coalitions working to improve STEM education. State Governors talk about STEM as important to their states.

It would be great to hear if STEM fever is something that you are involved in or has reached you? Let us know by taking a quick poll on the STEM education in your state.