feature

Starting With Science

Fifth-grade students develop speaking and listening skills while investigating food webs and habitats

Science and Children—July/August 2022 (Volume 59, Issue 6)

By Jesse Wilcox, Shawna Person, and Catherine Lyons

We’ve often heard from elementary teachers that they feel like they don’t have enough time to teach science. When elementary teachers feel pressured to focus on math and literacy, they tend to spend significantly less time on hands-on and exploratory science (Hayes and Trexler 2016). Indeed, elementary students often learn science when they are reading about science as a part of a literacy lesson. While reading about science has many advantages, exploratory science can help students to develop math and literacy skills (Shea and Shanahan 2020). In other words, starting with science lessons can provide rich experiences to build literacy skills. This article demonstrates how we used a 5E lesson about food webs as a context to embed speaking and listening standards (online Table 1). This 5E lesson partially addresses 5-LS2-1 in the Next Generation Science Standards and focuses primarily on predator/prey relationships. Future lessons focus on decomposition and other relationships. To help students connect to the materials, many of our examples early in the 5E are connected to the prairie because we live in Iowa. This could be adapted to other habitats.

Engaging Students With Preserved Specimens

Day 1 (45 minutes)

To start our investigation of prairie food webs, we invite the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) to bring in preserved plant and animal specimens. Most states have a DNR or college that may be able to send a visitor or lend preserved specimens. In our case, we have a nature center in our town. Pictures and videos could be used as a substitute, but we try hard to ensure students have experience with real organisms. Students are typically very excited to see the variety of specimens that can be found near where they live—everything from a beaver to various snakes. After a short presentation by our DNR representative, we discuss with students how to safely handle the specimens including how to hold them, how to ensure they don’t get damaged, and the importance of keeping themselves clean for the safety of the specimens and for their safety. Hand sanitizer is available for all students after handing specimens and we have all students thoroughly wash their hands prior to the start of the activity and after visiting all of the stations.

Once students understand the expectations, we usually have about eight stations set up where groups of three students get a chance to look at the specimens closely. We encourage the students to explore the specimens and then have them investigate the following questions:

- What interesting structures or parts do you notice about the plants and animals?

- What do you think those structures do for the plant/animal?

- Looking at the plant/animal, how do you think it gets food?

- What questions do you have?

Students get about three minutes at each station to observe and write down observations and questions on large whiteboards. To help support all learners but especially students learning English, we often give students sentence starters such as:

- I notice_______

- I wonder_______

- I see _______

As students rotate between stations, their jobs also rotate between facilitator, recorder, and materials manager. This connects to the speaking and listening standard of following discussion rules and carrying out assigned roles (CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.5.1.B). After students have completed each station and washed their hands, we come back together as a class. Since we have the DNR visitor on the first day, we spend the remaining time going through the questions students have on each whiteboard with the DNR visitor. Some questions include:

- Is ________dangerous?

- What does _______ eat?

- Where does _______ live?

- How many of them live around here?

- Where do the plants grow?

Day 2 (30 minutes)

While the DNR visitor has the stations set up, we take pictures of each organism. After school, we print the pictures for the next day. When students return to science on day 2, we distribute the pictures of the organism alongside the whiteboards students wrote on. Students then work in groups and return to the whiteboards to look at what they observed the day before. Once students have had a chance to refresh their memories, we have students look at the structure or “parts” of an organism and come up with some ideas about its function or “what the parts do,” such as how the long legs of a praying mantis help it catch prey. After students have had a chance to look at the organisms again, we help students connect structure/function to predator/prey relationships by asking, “What are some parts of the animal that would help it get food?” Students point out various parts such as the eyes on the owl help it see animals it would eat and the praying mantis has two front legs that would help it catch prey.

Exploring the Prairie Habitat

Day 3 (45 minutes)

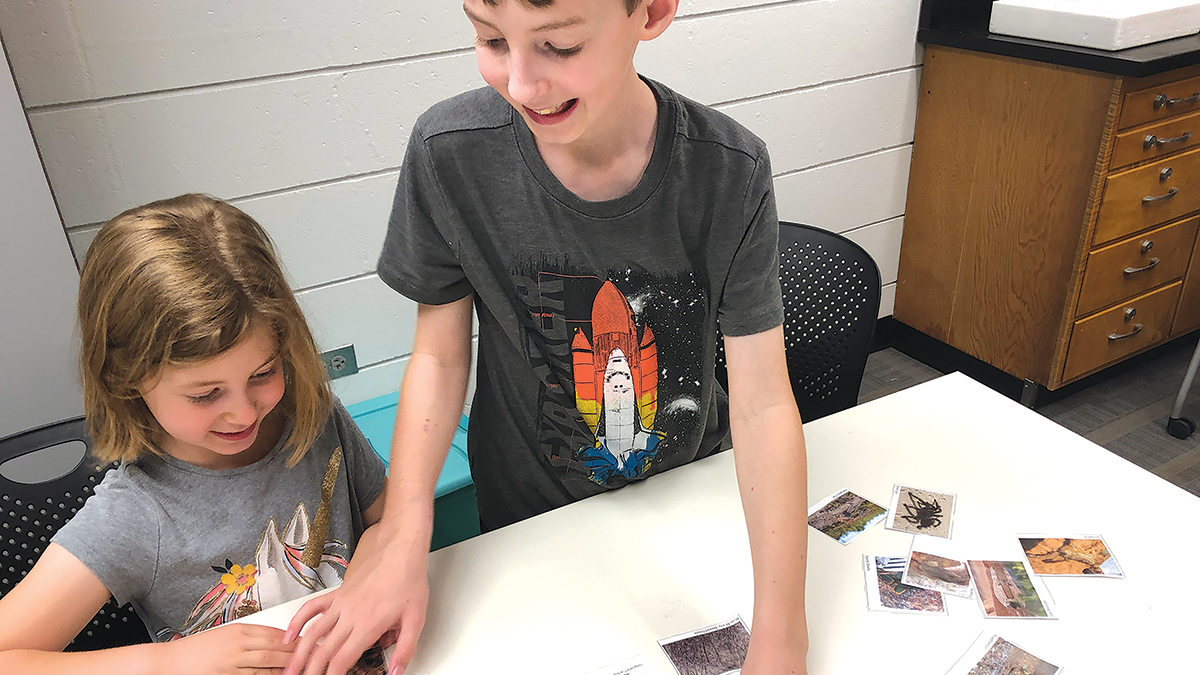

We split the students into small groups of four students and give each group a different set of pictures of plants and animals from the prairie (Figure 1). We have students look at each of the pictures and generate questions they have about the organisms in the pictures. Once students have had some time to think of questions, we bring them back together as a class and compile the list of questions. Students often ask things such as:

Sample pictures of prairie plants and animals.

- Where do they live?

- What do they do in the winter?

- Are they dangerous?

- How many of them live around here?

- How do they get their food?

- What eats them?

The students then use resources such as books and websites to answer their questions (see Resources). We differentiate by providing videos and texts that have a variety of reading levels to ensure we are supporting all students including those with special needs. To further support students, we often provide a list of plants and animals to help them figure out what organisms eat (see Supplemental Resources). We ensure students are investigating the relationships between organisms to help them make a food chain. Once students have finished researching their organisms, we have students summarize what they have learned (CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.5.2). We then ask: “What did you notice about what the things you had on your list eat?” Many of the students mention they found predators, prey, and which animals eat plants. They also often point out that animals eat other animals and plants on the list. We then ask, “How could you organize these pictures to show what eats what?” Students then work in teams to organize their pictures. Given we carefully selected the pictures each group received, students often end up with a food chain. For example, we make sure students get a picture of a plant, herbivore, predators, and apex predators.

Explaining Food Webs and Organism Interactions

Day 4 (30 minutes)

We start day 4 by having students walk around and look at other groups’ food chains. We take turns so each group gets a chance to quickly present their food chains to the rest of the class (CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.5.4). Students start to notice some overlap between the food chains, and we use that opportunity to ask, “What patterns are you noticing between the food chains?” Students point out that some of the animals and plants are the same. We then ask, “How could we put two chains together?” We work as a class to put two of the chains together. Afterward, we pair groups with another group to have them see where they link two chains together. We walk around the room and differentiate by asking questions such as, “Why might a mouse eat more than one thing?” and “How could you show that this animal is eaten by more than one animal?” In our experience, most of the students are able to make the connections across two food chains, which sets the stage for food webs the next day.

Day 4 (30 minutes)

After school, we make copies of each groups’ food chains and assess them to ensure each is accurate. We start science time on day 4 by asking, “What are some things you discovered when you worked with another group?” Students generally respond with, “Some predators eat things from both chains,” or “We can put our chains together.” When students express that the food chains overlap, we ask, “What do you think would happen if we tried to connect all of our chains?” Our students are often very excited to try it. We give students copies of each groups’ chains, large whiteboards or poster paper, markers, and scissors. Once we ensure students understand the tasks, they work in groups of four to connect the chains, which usually takes about 20 minutes. During this time, we walk around the room, scaffold students’ thinking, and differentiate as necessary. Students often end up creating something that looks like a food web.

Day 5 (30 minutes)

On day 5, each student group does a short presentation in front of the class to explain how they made a food web. These presentations serve as a formative assessment that helps us set students up for success when they do a summative assessment in the evaluate stage. After the presentations, we ask, “What are some things you noticed about all of the different food webs that you all created?” They often respond with: “All of our webs were very similar,” “all of the animals ate the same things in most of the webs,” and “we all had the same predator, prey, and plants and what they ate.” We then ask, “When we make food chains, why does it make sense to have the plants at the bottom?” Students often say, “They do not eat anything else, so it goes at the bottom,” “some animals eat plants, but plants do not eat animals,” “plants are where it all starts, for a food chain to start an animal has to eat a plant.” These students’ responses connect with the idea that the food of any kind of animal can be traced back to plants. We then ask students, “How do plants relate to animals that eat other animals?” Students often give some examples like, “Coyotes eat deer and deer eat grass, so predators like coyotes have to be related to plants because what they eat, eats plants.” This connection shows how energy moves throughout a food web.

Day 6 (30 minutes)

On day 6 we start with a question: “What would happen if we removed predators from the habitat?” We have students talk in groups and after a few minutes of discussion, we all come back together as a class to share ideas. We often get responses like, “We would have a lot of prey because there is nothing to kill them.” We then show students a clip called Planet in Peril: Yellowstone Wolves. This video provides a perspective on what happened when wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone. We pause the video in key places and draw a food web of how the wolves are impacting many species in Yellowstone and restoring balance to the ecosystem. Afterward, we ask, “Why is it important for a habitat to have a lot of species interacting?” Students note that each species affects others. We then discuss with students that a healthy ecosystem is one in which multiple species of different types are each able to meet their needs in a relatively stable web of life.

Elaborating Through Investigating a New Habitat

Days 7 and 8 (45 minutes each day)

To elaborate, students get to choose a different habitat to investigate the plants and animals that live there to make a food web poster. We split the students up into groups based on interest, group dynamics, and readiness. Students come up with a group name and we put those names into a random name picker called “Wheel of Names.” When their group name is drawn then they get to pick which habitat they want to investigate. We typically have students pick from the following list of habitats:

- Savannah

- Tropical Rainforest

- Temperate Rainforest

- Ocean

- River/lake

- Desert

Once groups pick their habitat, we give them books and a list of digital resources that have a variety of reading levels to find information on the animals and plants found in their habitat (see Resources). We differentiate by giving students a graphic organizer that already has some pictures and arrows filled in. While students get choices regarding the habitats and plants and animals they investigate, students need to include at least 12 plants and animals that are interconnected on their food web poster. Once students are ready for their poster, we give them poster board, scissors, markers, and crayons. Students can decide to either print pictures or draw pictures to represent how the plants and animals in that habitat are connected to one another. While students are making their posters, we walk around and scaffold students’ thinking by asking questions such as:

- Why might we want to put the plants at the bottom?

- How should you draw your arrows so we know what eats what?

- Why is it good for the habitat that you have so many connections on your web?

When students complete their posters (Figure 2), we have them present them in a gallery walk. We have half of the group stay with their poster and present it while the other half walks around and listens to other groups present. Students watching presentations also ask a question of the group that presents (CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.5.1.C). After two rounds of presenting, we switch so that the students who stayed move around and the students that moved get to present. This allows us to hear each student and their understanding of content and listen for any misinterpretations or content we need to elaborate on.

Sonoran Desert student poster.

Evaluating the Posters

As students are participating in the gallery walk presentations, we walk around the room, listen to students, and assess with a checklist (see Supplemental Resources). We look to see if students have developed an accurate model of a food web for their habitat. We listen to see if students discuss that all animals need plants and that a healthy ecosystem needs many organisms to thrive. The checklist also includes the Common Core speech standard (reporting on a topic using descriptive details to support main ideas and speaking at an understandable pace; CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.5.4).

Conclusion

Even though literacy is often a focus in elementary classrooms, science can be used as the context in which literacy skills can be developed. In this case, our students were excited to learn about plants and animals outside their own front doors as well as habitats from other places around the world. We found students were motivated to speak and listen to each other because they were genuinely interested in learning about food webs and habitats. ●

Supplemental Resources

Download the list of predators/prey, graphic organizer, and presentation checklist at https://bit.ly/3xMUKpj

Online Resources

Habitats/Biomes: enchantedlearning.com/biomes

Jesse Wilcox (jesse.wilcox@uni.edu) is an assistant professor of biology and science education at the University of Northern Iowa in Cedar Falls, Iowa. Shawna Person is an elementary education student at Simpson College in Indianola, Iowa. Catherine Lyons is a fifth-grade teacher at Morris Elementary School in Des Moines, Iowa.

Biology Earth & Space Science Interdisciplinary Literacy Elementary Grade 5