Teacher Spotlight

An interview with Alexandra (Allie) Mondini, Cincinnati, Ohio

Where do you teach? What do you teach? Describe the school, its resources and anything else that makes it a great place to teach.

I teach seventh-grade science, high school geology, and meteorology at Walnut Hills High School in Cincinnati, Ohio. I feel so lucky to be teaching at Walnut! We draw such a diverse group of talented students from all over the city, and I have the support of parents and the administration to provide many different outdoor learning opportunities for students. Walnut is also fortunate to have an active alumni foundation that provides a great deal of extra support and funding to our school. This is something that I think is probably unusual for a public high school, and I am forever grateful for their support! They have provided me with many different teaching resources over the years, and they have even sponsored scholarships for my students with financial need to participate in destination field trips.

What three things guided you in deciding to be a science teacher?

I have always been fascinated by the natural world, and I am forever captivated by this amazing planet that we live on. The conservation of Earth’s biodiversity is very important to me! I am also very passionate about social justice, and I have always had a great deal of empathy for other human beings. Becoming a science teacher seemed like a natural blend of these two life interests: I would be in a position to make a positive impact on the lives of young people, AND I would get to share my passion for this amazing planet with others! There was a brief period of time as an undergrad when I worried that I might not be happy teaching in a traditional school setting because I loved being outside so much. Eventually it occurred to me that by teaching at a public high school, I could create outdoor learning experiences for students that wouldn’t normally have access to those experiences. The challenge of that reinvigorated me!

You are about to start your 10th year of teaching. What types of outdoor learning opportunities have you created for your students so far?

I run a student backpacking club with my fellow science teacher and outdoor adventurer, Katie Sullivan. We teach students backpacking skills, take them on small weekend trips, and then culminate each school year with a weeklong trip on the Appalachian Trail. Field trips also offer great opportunities to get my students outside. My geology students go on a fossil-collecting field trip to a local state park each school year. Unfortunately, I am limited to only one field trip per class per year, so I get around this by offering “optional outdoor field trips” to students after school and on Saturdays sometimes. Not all of my students attend these extra-curricular field trips, but the ones that do have a good time!

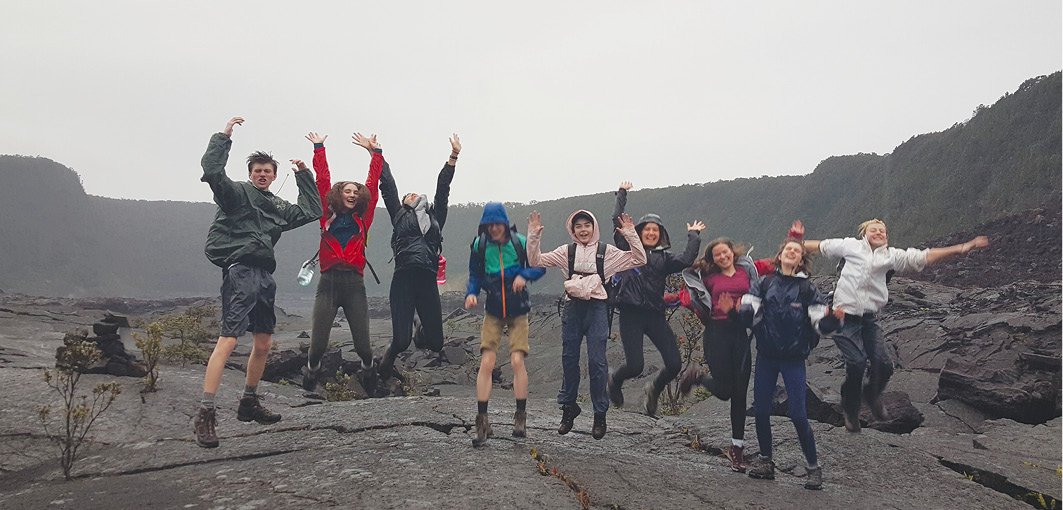

I have also started a 10-day geology field class that takes place over spring break each year. We go to Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, where we study the unique geology and ecology of the island and plug into local conservation work there. More recently, I’ve been working with students, Cincinnati Parks, and the Civic Garden Center to restore 10 acres of an urban woodlot adjacent to our high school. We have been removing invasive species, planting native trees and shrubs, and building a trail system. The goal is to increase local biodiversity and create a living land lab for students to use throughout the school year. One day, I hope to create an ecology elective in which students would design and implement their own field studies. Access to that space will create so many different outdoor learning opportunities!

Why do you think it is so important to get students outside?

There are so many compelling reasons! For one, we are living in a time when humans are growing up more disconnected from the natural world than ever before. People need nature! Countless studies have shown spending time outside in nature can reduce feelings of stress and depression and increase feelings of happiness and wellbeing. Our students are very stressed out. They are stressed out about school, grades, their social lives, and their future in a changing world. Providing them with opportunities to slow down, get outside, and just breathe can make a big difference in their mental health!

For another, how can we ever hope to solve the world’s many environmental problems if people are growing up without a personal connection to the natural world that we are rapidly losing? I also feel that as a profession, we don’t do a great job of providing hands-on, authentic learning opportunities for the natural sciences. For instance, we might provide a lot of laboratory experiences for classes like chemistry or physics, or maybe we engage anatomy students with dissections, but what about subjects like ecology or geology? You can’t wholly experience these fields of science in an indoor lab—you have to go outside! We should do better for our students—especially in a rapidly changing world where we need humans to understand Earth’s systems more than ever!

What safety precautions do you take with your field trips and environmental outdoor events?

When leading groups of students in the great outdoors, I think it is very important to make sure that the students are both mentally and physically prepared for the trip. For example, in our backpacking club, we don’t take students on the Appalachian Trail until they have completed at least a year’s worth of training prior to the trip. This training includes afterschool backpacking skills workshops, an overnight training trip to a nearby campground, and at least one smaller weekend trip to somewhere more local and less remote, like Red River Gorge or Cumberland Gap.

Students learn important safety skills, like how to dress properly for the elements, how to safely filter water, how to use a camp stove without burning oneself, how to hang a bear bag, how to check for ticks, etc. We also have mandatory “gear check” meetings prior to each trip. At these meetings, students bring their parents and their fully packed packs. That way, we can discuss trip rules, expectations, and safety together and address any lingering concerns that parents or students might have. We also check each student’s pack carefully to make sure they have enough layers, an adequate sleeping bag, enough food to eat, etc. We do the same thing for the Hawaii trip.

On the Hawaii trip especially, we have a long talk with parents and students about safety concerns on the island (riptides... lava) and really stress the importance of students following the directions of adults and not going off on their own.

I should also probably note that Katie and I have significant experience leading outdoor trips and that Katie has her Wilderness First Responder certification, so she can responsibly handle whatever medical emergency may come our way. We also make sure that all students fill out a detailed emergency medical form that we keep on us at ALL TIMES in case of emergency. Ultimately, what I want to stress here is that of course taking students on outdoor adventures comes with risk—the key is doing everything we can beforehand to minimize that risk.

What do you think is the best approach to take when teaching students about environmental problems?

One thing that really strikes me about students and environmental challenges is that most students really do care, but the problems they are inheriting from previous generations feel very overwhelming and depressing to them. My fear is that if we repeatedly bombard students with images and information about the destruction of our natural word, it will lead to feelings of helplessness, avoidance, and apathy. Obviously, we need to teach our students about environmental problems, but when we do so, I think it is equally important to also provide them with opportunities to tangibly engage in solutions to those problems. Sometimes, there is this mindset that unless you can do something really big for the planet, like preserve acres and acres of wilderness or sign a law into place, you don’t really have the power to make a difference, but any little thing we can do to get kids actually engaged in solutions empowers them to feel like they have some agency in this changing world, and THAT can make an enormous difference!

How do you build relationships with your students?

I think relationship building mostly happens in the in-between moments in class—those casual conservations you have with students before and after class, or perhaps while students are working in small groups and you are roaming around the room and having individual conversations with them. That’s one of the things I didn’t like about virtual teaching during the pandemic. I just felt like there were less opportunities for those get-to-know-each-other moments to organically happen.

I have also noticed that my closest relationships with students usually form through our shared participation in unstructured outdoor activities, like a backpacking club trip or a day spent planting trees. In the classroom, all these rigid structures are in place that put an invisible wall between teachers and students. Outside the formal setting of a classroom, it just seems easier somehow to connect with each other on a deeper level.

What project/lesson are you most proud of that you implemented throughout your teaching career? Describe the most ‘memorable’ lesson/project you use with your students.

I am most proud of the Hawaii field class that I have created. Even if the entire school year feels like a slog, I know that those 10 unforgettable days in the field make a lasting, positive impact on my students who participate. Once, while planting trees on the slopes of Mauna Kea, a student asked me what my dream job was. I said “This! Exactly this!” And I really meant it!

You’ve traveled with students to Hawaii before to study the geology of the islands. What is a standout memory from the response(s) of the students to this experience? How did you plan for such a big field trip?

Planning: I had a friend who was living on the Big Island, working in a captive breeding program for Hawaii’s most endangered bird species. After my first year of teaching, I spent a few weeks of the summer crashing on her couch and exploring the island. That’s when I first dreamed up the idea for the field class. I had taken a lot of destination field classes in college and they had really inspired me, so I used them as a template to create my own. I started with the question of “What do I want my students to get out of this experience?” From there, I compiled a list of learning objectives and built the itinerary of the trip around them.

Because I was physically on the island, I was able to visit trip destinations beforehand, scout hikes, and make personal connections with park rangers, volcanologists, snorkel vendors, and the Mauna Kea Forest Restoration Crew. That made planning for the trip a lot easier. It probably also helped that I was used to planning and leading big outdoor trips—I had been president of the Outdoor Adventure Club for a few years in college. I won’t lie—planning for a trip of this scale was a bear, but once I planned the initial trip, planning the trip for subsequent years got easier and easier.

Student Responses: Ack! It is hard to answer this question, because I am just overwhelmed with memories of in-the-moment student responses—just reactions of pure joy, wonder, and curiosity. What is really amazing to me, though, is the lasting impact this trip has on students. I have one student who now is a horticulturalist because he enjoyed planting trees on the mountain so much! Another student had been struggling with depression and anorexia throughout most of her teenage years. She wrote to me after the trip to let me know what a healing and inspirational experience it had been for her. I didn’t know it at the time, but on the trip she had worn a swimsuit for the first time in years, and she told me that she had been so wrapped up in the joy of her surroundings that she wasn’t even thinking about her body. She found a lot of inspiration in the constant rebirth and rejuvenation taking place on the island as well. After an eruption, the forest grows back. From destruction comes life!

Another student of mine had undergone a major spinal surgery in her early teens that had left her unable to walk for several years. She was walking by the time she signed on for the trip, but the rugged hiking and remote camping required by the trip were going to be real challenges for her. She wound up having the time of her life, and for her, the trip was physical proof that she could go anywhere and do anything—this injury was not going to hold her back! I have this amazing memory of being at Rainbow Falls and looking up and finding her 20 feet up in a tree with the BIGGEST smile on her face. That’s the thing about taking teenagers on outdoor adventures—it’s more than just them learning about the natural world. It also gives them the space they need to get to know themselves, challenge their limitations, find independence, and grow as humans!

.jpg)

What has been the most important lesson you learned from one of your students during your teaching career?

I once had a young woman in class who always seemed to have an attitude. She barely squeaked by with D’s, and I was convinced that she hated me. A year or so after graduation, she randomly dropped by my classroom to visit and proudly told me that she was at the top of her nursing class and preparing for a nursing abroad program! She had been inspired by stories of my travels and my advice to students to travel as much as possible after graduation. Prior to this, I had NO IDEA that my class had any impact on her at all! That was the lesson: to never underestimate a student and to always remember that grades do not accurately measure what a student is really getting out of my class!

What is one piece of advice you’d give to first-year science teachers?

The same advice my mom is always trying to give me: “Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good!” Your first year of teaching is going to be messy and imperfect, and you just won’t have enough time to implement all of the great ideas you have in your head. It’s okay! Try to look at the big picture and not to get hung up on the details. You are showing up for your students each school day and learning how to be a better teacher—that is a good thing, and it will get even better with time and practice!

Careers New Science Teachers Teacher Preparation Teaching Strategies High School