Early Childhood | Daily Do

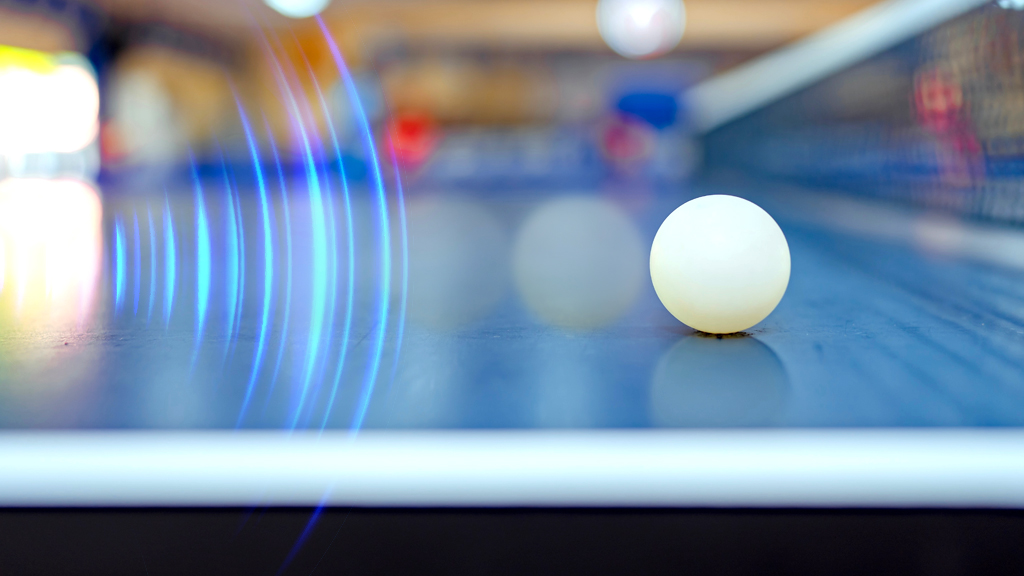

Why does the ping pong ball move?

Crosscutting Concepts Is Lesson Plan NGSS Phenomena Physical Science Science and Engineering Practices Three-Dimensional Learning Early Childhood Grade 1

Sensemaking Checklist

Introduction

In today’s task, Why does the ping pong ball move?, students’ develop an understanding that objects that make sound vibrate and that sound can make things vibrate. Students use the practices of planning and carrying out investigations to make observations and developing and using models to figure out the cause and effect relationship between sound, vibrations, and the mysterious movement of the ping pong ball.

Introducing the Phenomenon

Tell students you have a really puzzling phenomenon to share and hope we can work together to figure out how this phenomenon occurs. Show them the Why does the ping pong ball move? video.

After watching the video, ask students to write or draw what they observed. (Consider playing the video more than once.) Students should also record questions they have about what they observed. Have students share their observations and questions with a partner before sharing them with the class. Record students’ observations and questions on a Notice and Wonder chart that is visible for the whole class. Students are likely to share observations and questions such as:

- The girl hit “tuning fork 1”

- Tuning fork 1 made a noise when she hit it

- The ping pong moved after she hit tuning fork 1

- What are tuning forks?

- Why are there two tuning forks?

- Did turning fork 2 make a noise?

- Why does the ping pong ball move?

Guidance: Help students focus on making observations with their eyes and ears (the what) rather than attempting to explain why the ping pong ball is moving (the why). You might even say to them, “We’re focussed on the what right now, not the why.” Students are likely to have different experiences with objects making sound. Using phenomenon to engage students in the practice of asking questions leverages students' natural curiosity to motivate learning. You can refer back to students' questions to track the class’ progress in making sense of the phenomenon and to create the need for them to engage in the investigations.

Sharing and Building On Our Thinking

Explain to students that first the class is going to make a model to help them figure out what is causing the ping pong ball to move. Have students work in small groups to determine what parts will need to be included in their model. Create a class list of parts by having each group take turns sharing one part they think should be included in the model. Once groups have shared all of their parts, discuss with the class if there are any parts they feel were left out or that should not be on the list. Start the class model by drawing all of the parts from this class list.

Guidance: This model should represent ideas agreed upon by the class. Encourage students to agree, disagree, and discuss the parts that should be included. If the class is split, you might suggest including the part and drawing a question mark next to it (or drawing the part using a dashed line).

Next, have students work in groups to describe all the things that happened that resulted in the ping pong ball moving (for example, the girl hit tuning fork 1, tuning fork 1 moved, tuning fork 1 made a noise). Consider supporting students in organizing their ideas about the sequence of happening by using a tool such as a comic strip or before, during, after chart. After groups discuss the sequence of happenings, have them share their thinking with the rest of the class. As you add each happening to the model, encourage students to agree, disagree, and discuss these steps. Return to the video if students are unable to come to consensus and then continue to discuss.

After this model has been created, have students revisit the class Notice and Wonder chart. Take time for students to add new questions to this chart. Have students discuss in their small groups what they think might be causing the ping pong ball to move. They can share these ideas with the class. As students share, help them make their thinking visible by using talk moves such as:

- Can you tell me more about that?

- What have you seen that makes you think that?

- How is your idea similar or different from other classmates?

Tell students we need evidence to answer our questions and you have some investigations they can do that might provide the evidence we need.

Guidance: The use of the notice and wonder chart and class model to facilitate collaborative sensemaking of the phenomenon. Having a class model, that is informed by student ideas, creates a visible representation of the collective understanding of the class. At this point, the class model should represent student ideas rather than a complete and accurate description of the phenomenon. Students will add to the model as new evidence is found. Read more about the practice of modeling and its role as a sense making tool in this Face to Face Tools: Making Changes in Student Thinking Visible Over Time from Ambitious Science Teaching.

Investigations

These investigations can be set up in stations with student groups moving from station to station or the whole class can participate in the same investigation one investigation at a time.

Investigation 1: What happens when I hit a tuning fork?

Have students hit a tuning fork with a rubber mallet (or strike the sole of their shoe with the tuning fork) and gently touch it with their fingers. Students should write or draw what they observe. Students should notice that the tuning fork makes sound when struck, and that they feel a “buzz” on their fingers when they touch it. They should also notice they can stop the sound the tuning fork makes by using a harder touch or grasping it.

In small groups, have students discuss what they observed and if their observations provide evidence to explain the phenomenon of the ping pong ball moving when the far away tuning fork was struck. Students should use this evidence to explain that when the tuning fork is struck it makes sounds and begins to “buzz” in the phenomenon. Have these groups discuss where this evidence fits on their class model.

Guidance: All students may not be familiar with the term vibrating. All students should experience and describe this term before providing them with the definition. For example, students may explain that the “buzzing” is the tuning fork moving back and forth quickly. Allow students to use these descriptions and continue to build their understanding of vibrations rather than providing them with the vocabulary word.

Investigation 2: What does the tuning fork look like in slow motion?

Tell students that you are going to show a Tuning Fork Vibrating in Slow Motion (videos) to see if that helps them explain the “buzzing” they felt when the tuning fork was struck. Students should write or draw what they observe.They should observe that the tuning fork moves back and forth after it gets hit.

In small groups, have students discuss what they observed and if their observations can be used as evidence to explain the phenomenon. Students should be able to use their observations of the slow motion tuning fork as evidence to support the idea that “Tuning Fork 1” vibrates after it gets struck in the phenomenon. Have students work in their groups to discuss how this explanation can be added to the class model.

Guidance: Because students have had enough experience with the term at this point, it is ok to introduce the vocabulary word “vibrate” to describe the back and forth motion of the tuning fork. Students may need support in understanding that not all of the observations they make from the investigations can be used as evidence to help explain the phenomenon. For example, “the video is in black and white,” is an observation that students may make, but it does not help us explain why the ping pong ball moves.

Investigation 3: What do other objects that make sound look like in slow motion?

Have students watch the videos of the guitar, drums, and speaker in slow motion. Have students write or draw what they observe.

Students should notice that all of the objects vibrate like the tuning fork vibrates when struck or plucked. Have students work in small groups to share their observations and discuss where this evidence fits into the model. Using students' ideas and observations, add the explanation that objects that make sound vibrate.

Investigation 4: How can an object vibrate without hitting it?

Have students place a speaker in a container and cover the container with parchment paper. Speakers from a cell phone will work. Use a rubber band to hold the parchment paper tight on the container. Place salt on the parchment paper and have the speaker play a song. Students should write or draw what they observe.

Students should notice that when the speaker is making sound the salt moves because the parchment paper is vibrating. When the speaker is not making sound, the salt does not move because the parchment paper is not vibrating. Have students work in small groups to share their observations and discuss where this evidence fits into the model. Using students' ideas and observations, add the explanation that Tuning Fork 2 vibrates from the sound of Tuning Fork 1.

Coming to Consensus

Have students work in their groups to answer the question, “Why does the ping pong ball move when tuning fork 1 is struck?” Encourage students to use the class model to help them sequence the happenings (interactions between parts) that cause the ping pong ball to move. Use the groups’ explanations, the class model, and student observations to explain why the ping pong ball moves. To support students in connecting the evidence they collected in the investigations with their explanation use “talk moves” that encourage the use of reasoning. For example:

- How do you know the tuning fork vibrates when it gets struck?

- How do you know that sound can make objects vibrate?

The final class model should show:

- In the beginning, nothing is moving. The ping pong ball is touching tuning fork 2

- Tuning fork 1 moves back and forth when it is struck and makes noise

- The sound from tuning fork 1 makes tuning fork 2 move back and forth (students may not be able to explain the mechanism and this is OK)

- The ping pong ball is touching tuning fork 2

- Tuning fork 2 hits the ping pong ball

- The ping pong ball starts moving back and forth