The sensor is fairly small compared to an iPad Air.

The new Go Wireless Temp sensor is a welcome addition to the suite of Bluetooth tools produced by Vernier that are available for the iPad. While not much larger than the business end of the traditional, wired temperature sensor, the Go Wireless Temp has onboard power and a radio transmitter all nestled in a thumb-sized, water-resistant housing. Although the device’s temperature range is a little narrower on the upper end due to its plastic and electronics, it still safely measures molecular motion from -40°C to 125°C. While the merits of digital temperature probes are well known, and the benefits of wireless peripherals have promoted collaboration and creativity in the science classroom, the Go Wireless Temp has added a new dimension with its light weight, free accompanying app, and 30-meter range. I took the Go Wireless Temp for a spin, looking for ways to leverage the wireless potential of the sensor.

The Go Wireless Temp must be used with a mobile device. To use the sensor with an iPad, you can download either the Go Wireless Temp app, available for free through the iTunes store, or the Vernier’s Graphical Analysis app, available for $4.99, for more powerful data collection and analysis.

The sensor is hanging on a 6-meter cord with its tip in the current.

To test the sensor, I attached it to a paracord harness and lowered the sensor off a bridge and into the center of a stream. Once the Go Wireless Temp was tied to a railing, the iPad interface could pair with the sensor and record the temperature anywhere within radio frequency sphere with a 30-meter radius.

A screenshot of the Go Wireless Temp app’s autoscaled presentation of the data.

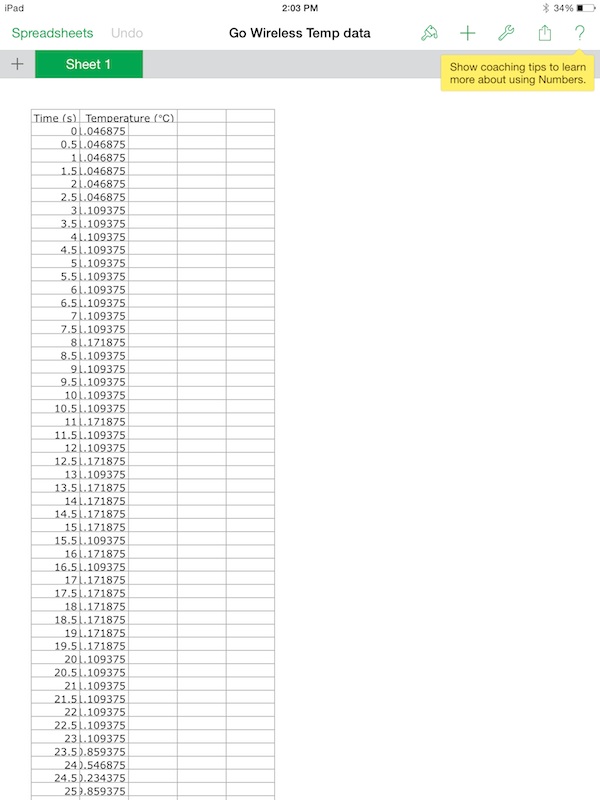

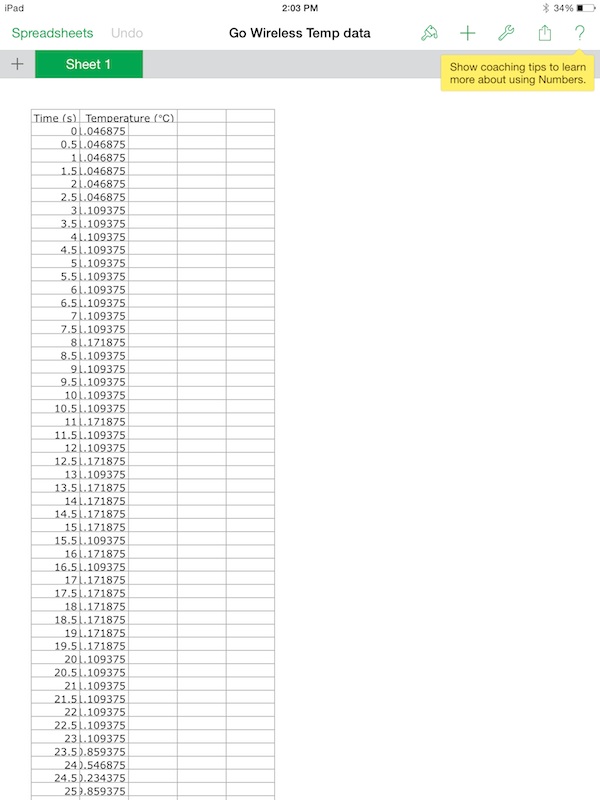

The data from the Go Wireless Temp app can export directly into an iPad spreadsheet app called Numbers. This is a screenshot of the river data, as exported.

The sensor is tied to a branch.

Next, the Go Wireless Temp was tied to a branch so it could be inserted precisely into various water pools. First, it was lowered into a fast-flowing current, then into a nearby still pool, and finally into the water collected inside an old tire.

Based on my tests, it will take at least 10 seconds to get the reading into the ballpark of its final value. The Go Wireless Temp is submersion-rated to 1 meter for 30 minutes.

The sensor at the end of a branch being dipped into the strong current.

Using the stick method, the sensor takes the temperature of the tire. It is warmer than the surrounding water.

The three temperature readings of the air, the water near the tire, and the water in the tire.

But the coup de grâce of my afternoon adventures was duct-taping the sensor to a quadcopter drone and flying it. At first, the merits of mounting a sensor with a limited range on something with a much larger range seemed questionable, but the temperature would be recorded as long as the sensor was in range, and the drone wouldn’t fall to the ground when the sensor lost communication.

The sensor is duct-taped to the underside of the drone.

So, why did I put a Go Wireless Temp on a drone? I guess the easy answer is because I could. But in reality, I saved answering that question until after it was flying. One reason was to measure the temperature radiating off of various roof surfaces, roads, and foliage areas. Another reason was to suspend the probe on a harness, like noted above, and dip it into bodies of water or locations in the water that are normally inaccessible.

One hundred vertical centimeters might be a challenge to fly, but the real issue is the weakened radio strength when the probe is underwater. One solution, which I’ve yet to build, is a personal flotation doughnut, or PFD, for the Go Wireless Temp probe. A small disk of expanded polystyrene (Styrofoam) with the probe poked through the center would allow plenty of slack to build the vertical buffer for safer flight and a much greater margin for error. Stay tuned for that one!

So what would you do with a Go Wireless Temp sensor?

Share your creative ideas in the comments.

The drone can easily carry the sensor far beyond its 30m range.

A previous question from a teacher related to using the peer-editing process in science class. Jaime Gratton follows up with a summary of her experiences:

A previous question from a teacher related to using the peer-editing process in science class. Jaime Gratton follows up with a summary of her experiences:

“Think globally, act locally” is a phrase we hear, and for younger students, thinking locally is important, too. Earth Day is celebrated on April 22, but the activities and investigations described in this month’s featured articles go beyond a single day and encourage students and teachers to consider what happens in their own lives and backyards or neighborhoods.

“Think globally, act locally” is a phrase we hear, and for younger students, thinking locally is important, too. Earth Day is celebrated on April 22, but the activities and investigations described in this month’s featured articles go beyond a single day and encourage students and teachers to consider what happens in their own lives and backyards or neighborhoods.