Last week President Trump issued a presidential memorandum calling for a $200 million boost to STEM education and computer science in K–12 schools. The memorandum, signed during an Oval Office ceremony attended by Ivanka Trump and U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, is intended to help make STEM education a bigger priority for schools.

“My administration will do everything possible to provide our children, especially kids in underserved areas, with access to high-quality education in science, technology, engineering and math,” Trump said during the ceremony.

To focus on STEM and computer science the Department of Education will be asked to create a priority for these areas in existing discretionary federal grants, to be determined by ED, to the tune of $200 million. Grants that emphasize female and minority students in STEM/computer science will be given additional priority. The Administration is expected to announce the priorities soon.

Education Secretary DeVos was also tasked by the President to explore administrative actions” that would enhance computer-science education.”

As you will recall, former President Obama also called for a push to include more coding and STEM in the school curriculum, but the initiative was never funded.

The day after the White House announcement, Ivanka Trump went to Detroit and met with a number of major tech companies—including Amazon, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Lockheed Martin, Accenture, General Motors and Pluralsight—that have pledged $300 million over the next five years to the administration’s efforts in STEM. Read more the Detroit meeting here.

More about the Administration’s STEM initiative here and here.

The Administration’s focus on STEM and computer science comes after a proposed $9 billion cut to the Education Department funding, including the elimination of two key programs in ESSA that would greatly benefit STEM and computer science—Student Support and Academic Enrichment Grant (SSAEG)Title IV and the Preparing, Training, and Recruiting High-Quality Teachers, Principals, and Other School Leaders Title II.

Superintendents from California, Oregon and Washington Advocate for Title II Funding

State superintendents from California, Oregon and Washington have sent a letter to Congress advocating for the continuation of Title II funding in the 2018 federal budget. ESSA Title II funds are used for teacher professional learning and other initiatives that impact teachers; earlier this year the House of Representatives eliminated the Title II funding from its budget, which drew loud criticism and pushback from key administration and teaching groups, including NSTA.

Read more about Title II and how you can speak up and take action to save this program here.

Update on Every Student Succeeds Act

Most states have now complied with the Sept. 18 deadline to submit their plan to implement ESSA. Understanding ESSA has a nice compilation of state plans here, take a look and see if your state has included language on science or STEM in their plan.

Education Week did a great one-stop-shopping guide to ESSA, check it out here.

They also answer the question How Are States Looking Beyond Test Scores? noting that “states including Kentucky, Nebraska, Utah, Rhode Island, as well as Delaware and Louisiana, added science proficiency into the mix.”

James Brown, executive director of the STEM Education Coalition, joined Lab Out Loud co-hosts Brian Bartel and Dale Basler to talk about ESSA, how it impacts states and STEM education, and how teachers can get more involved as this law rolls out. Listen to the podcast here.

NSTA’s powerpoint on ESSA and Science/STEM can be found here

TITLE IV Coalition Holds Senate Briefing on SSAE Grant Program

NSTA was pleased to be part of the Title IV-A Coalition policy briefing in the Senate held earlier this month on the Student Support and Academic Enrichment Grant (SSAEG) program authorized in the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

The briefing looked at three major aspects of the grant program, which supports well rounded programs (including STEM), technology, and health and safety programs.

Alyson Klein, a federal policy reporter for Education Week, moderated three round tables, one for each area. Senate staffers heard from a mix of education experts, parents, counselors, and doctors all in support of Title IV, Part A and its significance.

NSTA Associate Executive Director Al Byers served on the first panel, which discussed technology in education. Byers spoke to the need for quality professional learning for all teachers, especially teachers of science. Panelists on the third panel advocated for well-rounded education and the importance of diverse academic programs, including STEM, music, art, and physical education. Vanessa Ford, Director of Teacher Training, Curriculum and Evaluation at REAL School Gardens and a long-time advocate for STEM education, represented STEM on this panel.

The last group of panelists centered on health and safety programs and discussed the research supporting that a healthy lifestyle—physically and mentally—advances overall academic performance and success.

Congresswoman Suzanne Bonamici (D-OR) keynoted the event, and thanked the Coalition for their continued advocacy and support for Title IV funding.

Although the program is authorized at $1.6 billion, FY17 programs are funded at only $400 million. With this low level of funding, the panelists stressed how school districts will soon have to make tough decisions on where to allocate their appropriations among the three priorities listed above. They urged Congress to fully fund Title IV. Learn more about the Title IV Coalition here.

And last but not least …

The Council of Chief State School Officers is out with a new “playbook” on preparing teachers that shares best practices from states. Transforming Educator Preparation: Lessons Learned from Leading States can be found here.

Jodi Peterson is the Assistant Executive Director of Communication, Legislative & Public Affairs for the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) and Chair of the STEM Education Coalition. Reach her via e-mail at jpeterson@nsta.org or via Twitter at @stemedadvocate.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

The

The  I am K-6 science specialist in Australia. I am keen to make contact with others in this unique employment situation. I’m interested in issues such as timetabling (scheduling), support from the school, and any issues with the teachers’ union. – C., New South Wales

I am K-6 science specialist in Australia. I am keen to make contact with others in this unique employment situation. I’m interested in issues such as timetabling (scheduling), support from the school, and any issues with the teachers’ union. – C., New South Wales

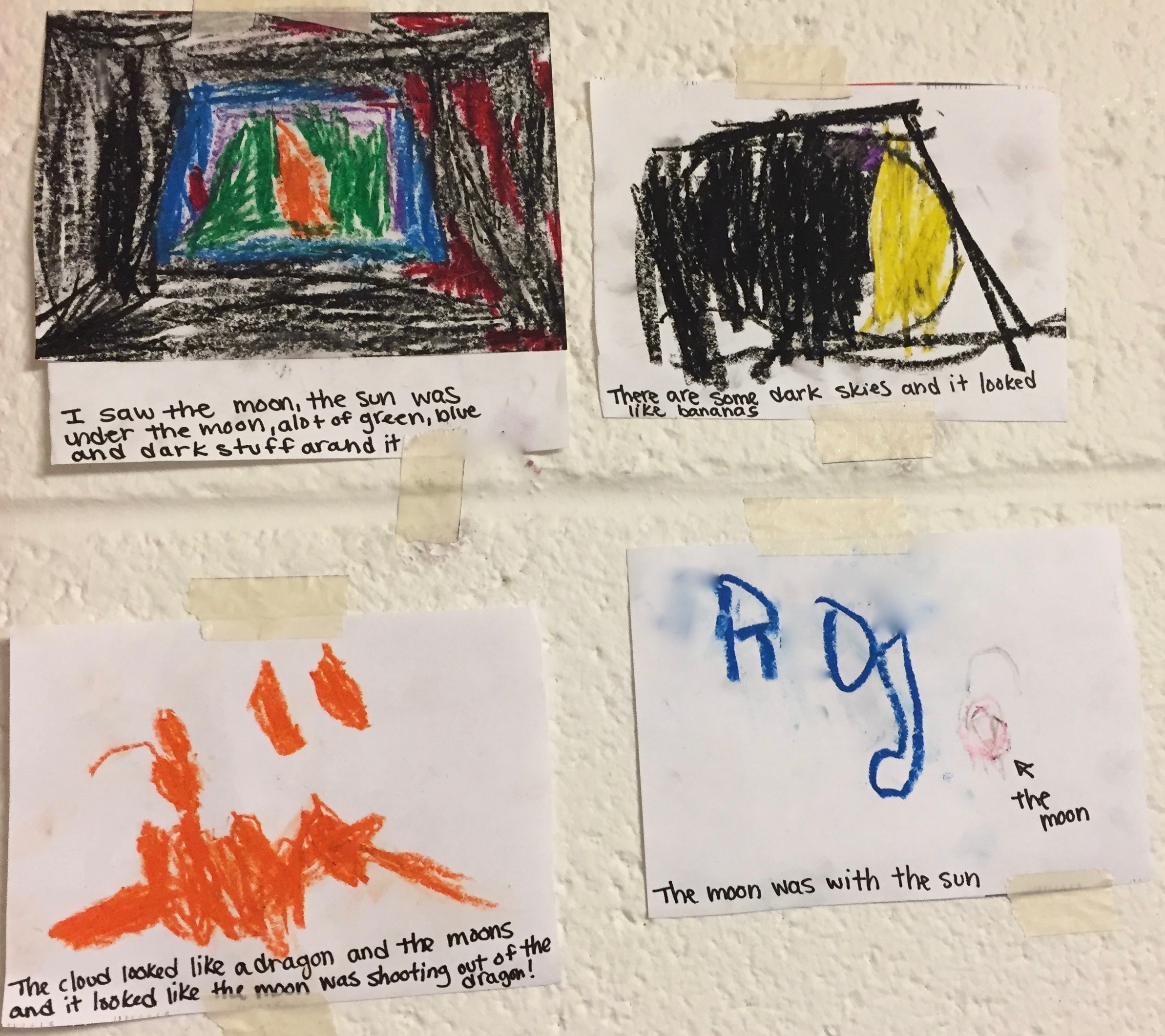

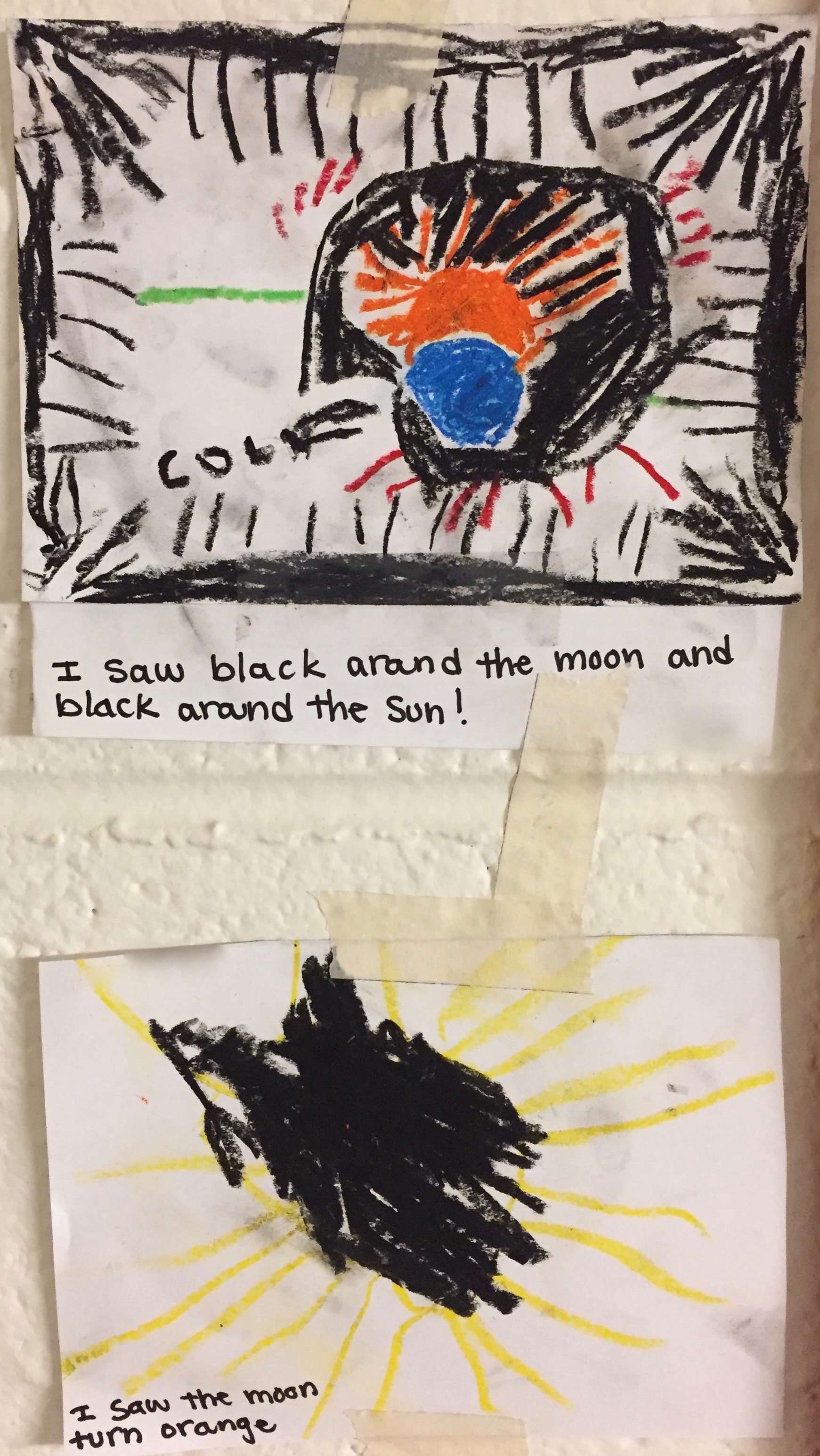

That afternoon, the three and four year old classes played in the large muscle (gross motor) room indoors with moon-themed centers while a few children at a time, with the direct assistance of adults, took turns viewing the solar eclipse, each spending at least five awestricken minutes outside. Originally teachers planned for the entire group to go out together and stay outside for a long period of time but researching how to make it a safe experience led them to take the children out in small groups instead, for multiple short viewings of five minutes with adults more directly supervising the children’s use of glasses. The children’s documentation shows what an impact this experience had on them.

That afternoon, the three and four year old classes played in the large muscle (gross motor) room indoors with moon-themed centers while a few children at a time, with the direct assistance of adults, took turns viewing the solar eclipse, each spending at least five awestricken minutes outside. Originally teachers planned for the entire group to go out together and stay outside for a long period of time but researching how to make it a safe experience led them to take the children out in small groups instead, for multiple short viewings of five minutes with adults more directly supervising the children’s use of glasses. The children’s documentation shows what an impact this experience had on them.