Fill your summer with science

By Claire Reinburg

Posted on 2015-07-10

Gaze at the Moon, follow the NASA New Horizons probe on its flyby of Pluto, or take a nature walk to benefit your brain. This is the time of year when science teachers get to choose their own adventures! Check out a few of our suggestions from this month’s issue of NSTA’s Book Beat, and enjoy a science-filled summer.

Gaze at the (Blue) Moon

Did you know that we’ll have a second July full Moon on July 31? According to EarthSky.org, it will be 19 years until we see a “blue Moon” in July again. Refresh your knowledge of the Moon with the informative and engaging NSTA Kids book Next Time You See the Moon, by Emily Morgan. Selected from more than 600 titles by a nationwide panel of 12,500 children for a 2015 Children’s Choices award from the Children’s Book Council and the International Literacy Association, this photograph-rich book conveys essential information about the Moon in a style sure to interest adults and children alike. Browse the other Children’s Choices winners for ideas for your classroom or home library.

Did you know that we’ll have a second July full Moon on July 31? According to EarthSky.org, it will be 19 years until we see a “blue Moon” in July again. Refresh your knowledge of the Moon with the informative and engaging NSTA Kids book Next Time You See the Moon, by Emily Morgan. Selected from more than 600 titles by a nationwide panel of 12,500 children for a 2015 Children’s Choices award from the Children’s Book Council and the International Literacy Association, this photograph-rich book conveys essential information about the Moon in a style sure to interest adults and children alike. Browse the other Children’s Choices winners for ideas for your classroom or home library.

View Pluto up Close

After nine years and three billion miles, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft will make its closest approach to Pluto on July 14. Tune in to the coverage online and follow along as New Horizons shares data and images of Pluto and its moons. If planets, stars, and objects in the night sky are part of your curriculum next year, check out the helpful formative assessment tool “Is It a Planet or a Star?” from Page Keeley and Cary Sneider’s Uncovering Student Ideas in Astronomy. This formative assessment probe is designed to elicit students’ ideas about visible objects in the night sky and reveal whether students know how to spot a planet and can distinguish it from a star.

After nine years and three billion miles, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft will make its closest approach to Pluto on July 14. Tune in to the coverage online and follow along as New Horizons shares data and images of Pluto and its moons. If planets, stars, and objects in the night sky are part of your curriculum next year, check out the helpful formative assessment tool “Is It a Planet or a Star?” from Page Keeley and Cary Sneider’s Uncovering Student Ideas in Astronomy. This formative assessment probe is designed to elicit students’ ideas about visible objects in the night sky and reveal whether students know how to spot a planet and can distinguish it from a star.

Boost Your Brain With a Nature Walk

Recent studies provide evidence that connecting with nature through hiking or outdoor walks brings health benefits beyond what we previously knew, including positive mental health effects. Make nature walks part of your summer routine, and immerse yourself in observing plants, animals, weather patterns, or other natural phenomena that draw you in. Check out Scientific American’s clever summary of the ways exercise gets the brain in shape.

SUMMER Savings on NSTA Press Books

If catching up on your professional reading is on your to-do list this summer, NSTA Press is here to help with special savings on books and e-books. Between now and August 14, 2015, take 10% off your online order of NSTA Press books or e-books at the NSTA Science Store by entering the promo code SUMMER at checkout. Browse the NSTA resources that your fellow science teachers are reading, or peruse the current bestsellers in the Science Store for ideas on building your teaching resource library.

Meters, liters, and grams

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2015-07-09

Do you have any suggestions for how I can help my middle school students understand and use the metric system? We struggle with this at the beginning of every year. –E., Indiana

Do you have any suggestions for how I can help my middle school students understand and use the metric system? We struggle with this at the beginning of every year. –E., Indiana

It’s hard for U.S. students to get a handle on meters, liters, and grams when in their everyday lives they are surrounded by references to miles, feet, inches, quarts, and pounds (one exception being a two-liter bottle of soda). We can’t change what’s on television or on the internet, but we can require that students use International System (SI) units and measurements in their science activities, investigations, and reports.

The first textbook I used had a chapter devoted to the metric system, so I would dutifully “cover” it at the beginning of the year, supposedly to prepare students for future investigations. The students memorized the prefixes, and there were exercises in measuring classroom objects. The chapter had a heavy emphasis on converting units from metric to English or vice versa. What a disaster! I felt like I was teaching more arithmetic than science. Even though we practiced measuring things with metric rulers, graduated cylinders, and balances, I found that later when it came time to actually apply those skills in investigations, my students had forgotten (or claimed to have forgotten) much of what they “learned.”

When I reflected on this, I realized that I had expected the students to master these concepts, skills, and vocabulary without a meaningful context for them. It seemed difficult for them to apply processes introduced at the beginning of the year to an activity weeks later. I was certainly teaching the material (with the lesson plans to prove it), and the students seemed to know the material at the time. But they weren’t learning it well enough to apply it to new activities without a lot of review and re-teaching.

So in the following years I changed my approach. I decided to introduce only those SI/metric measures that are commonly used: kilograms, grams, and milligrams; liters and milliliters; kilometers, meters, centimeters, and millimeters. That’s it. I mentioned that other units such as decigrams or centiliters exist but are seldom used. (I’ve traveled a lot in Europe, Canada, and Australia and I never saw anything measured in hectograms or kiloliters!)

I introduced or reinforced these units within the context of investigations, rather than as separate and isolated topics of instruction. When we came to an investigation requiring liquid measurements, we first practiced with graduated cylinders and discussed the relationship between milliliters and liters. Students had a section in their notebooks for notes and drawings on measurements that they could use as reminders in future activities. I also found that students knew more than I had assumed.

We didn’t spend time on problems converting miles to kilometers or grams to ounces. It’s not worth it, and now most smart phones, tablets, and computers have apps that do these conversions. Students should know which SI units correspond to the ones they are more familiar with in the United States. For example, in much of the world meat and butter are sold in kilograms instead of pounds, distances between places in kilometers, gasoline and milk in liters, and so on.

I always had a few students say “Why do we have to measure this way?” which is a good question. I would mention that science research around the world uses SI measurements. The United States, Myanmar, and Liberia are the only nations in the world that do not use SI as the official system of weights and measures. But I clinched the discussion by asking students, “Who likes to play with fractions?” Very few hands were raised. When the students compared adding 1/8 inch and 3/16 inch vs. adding 3 mm and 4 mm they were convinced.

See the websites:

Meaningful Metrics with Dramatic Demonstrations

Photo: NASA

Do you have any suggestions for how I can help my middle school students understand and use the metric system? We struggle with this at the beginning of every year. –E., Indiana

Do you have any suggestions for how I can help my middle school students understand and use the metric system? We struggle with this at the beginning of every year. –E., Indiana

Start Your App Search With a Question

By sstuckey

Posted on 2015-07-08

[youtube]https://youtu.be/LL4n4nq0DDc[/youtube]

In this video, columnists Ben Smith and Jared Mader share information from their Science 2.0 column, “Start Your App Search With a Question,” that appeared in the Summer issue of The Science Teacher. Read the article here.

[youtube]https://youtu.be/LL4n4nq0DDc[/youtube]

In this video, columnists Ben Smith and Jared Mader share information from their Science 2.0 column, “Start Your App Search With a Question,” that appeared in the Summer issue of The Science Teacher. Read the article here.

NSTA at #ILA15: Hands-On Science + Literacy Solutions

By Lauren Jonas, NSTA Assistant Executive Director

Posted on 2015-07-07

The 2015 annual conference of the International Literacy Association (ILA) takes place July 18-20. Featuring general session speakers Shaquille O’Neal, Octavia Spencer, Shiza Shahid, and Stephen Peters, the conference organizers state: “Illiteracy is a solvable problem, and together, we can make a difference! Amplify your efforts by joining forces with us at ILA 2015 in St. Louis, where you’ll get information and inspiration to transform your students’ lives. “ The National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) will be there to join this meaningful movement, resolved to end illiteracy.

NSTA’s position on Elementary School Science states “we support the notion that inquiry science must be a basic in the daily curriculum of every elementary school student at every grade level.” And we believe that science is a key component of a complete and rigorous curriculum for all students. Supported by our community of expert educators with a solid science education background and a passion for literacy, we’ve assembled a powerful resource collection that helps integrate science and literacy at the elementary level. Join us in St. Louis, Missouri, July 18-20 to learn more, and stop by our booth to share your ideas with us about the direction in which you see education going.

When you do visit us, whether onsite or online, we hope you will sample some of our resources:

- Professional journals, packed with science teaching techniques, lessons, and activities

- Classroom-tested tools for integrating science and literacy in elementary classrooms

- Formative assessment strategies that thousands of educators are using now

- Quick reference guides to NGSS implementation

- NSTAKids books… fun for kids, accurate science for teachers

Visit booth #524 onsite to learn more, and don’t miss these special events:

In-Booth Events

Saturday, July 18

11 a.m.–5 p.m. Meet NSTA Retiring President Juliana Texley

11 a.m.–12 p.m. Book signing by Picture Perfect Science authors Emily Morgan and Karen Ansberry

1 p.m.–2 p.m. Book signing by Picture Perfect Science authors Emily Morgan and Karen Ansberry

2 p.m.–4 p.m. Book signing by Inquiring Scientists, Inquiring Readers author Jessica Fries-Gaither

Sunday, July 19

10 a.m.–12 p.m. Book signing by Inquiring Scientists, Inquiring Readers author Jessica Fries-Gaither

4 p.m. Book Raffle! Complete Set (6) of the “Next Time You See” NSTA Kids book

Sessions

Saturday, July 18

3 p.m.–5 p.m.

Session: Picture Perfect Science: Using Children’s Literature to Guide Inquiry

Karen Ansberry and Emily Morgan

Session #00280

Room 229

Monday, July 20

11 a.m.–12 p.m.

Session: Science as a Vehicle for Improving Literacy Skills

Jessica Fries-Gaither

Session #00281

Room 225

1 p.m.–2 p.m.

Session: Choosing and Using Great Science Trade Books

Juliana Texley and Suzanne Flynn

Session #00793

Room 242

Can’t make it to the booth? Use promo code ILA15 online at the NSTA Science Store to receive the same 20% discount on all NSTA Press publications* that our members get—plus $5 off NSTA membership for yourself or a science teacher on your team!

*Offer good only on NSTA Press publications, from July 11–August 31, 2015, and cannot be combined with any other offer or discount.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

NSTA President Carolyn Hayes Welcomes NSTA's New Committee, Advisory Board, and Panel Members

By Guest Blogger

Posted on 2015-07-06

On behalf of the leadership of the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA), NSTA staff, and NSTA members, I would like to welcome and thank the NSTA members listed below, who are newly serving on our Standing Committees, Advisory Boards, and Panels; their terms of appointment began on June 1, 2015, and they’ve already begun doing important work like planning for our upcoming area conferences, getting the word out about legislation affecting teachers across the United States, and reviewing our journals and other publications!

On behalf of the leadership of the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA), NSTA staff, and NSTA members, I would like to welcome and thank the NSTA members listed below, who are newly serving on our Standing Committees, Advisory Boards, and Panels; their terms of appointment began on June 1, 2015, and they’ve already begun doing important work like planning for our upcoming area conferences, getting the word out about legislation affecting teachers across the United States, and reviewing our journals and other publications!

With the adoption of the NSTA Strategic Goals each committee, advisory board, and panel will focus on some aspect of the implementation plan for the upcoming year. We will strive to not only strengthen our organization through better engagement of the membership but also equip science educators to be advocates, to strengthen elementary science education, to implement NGSS practices through STEM, and to utilize NSTA resources for their professional learning.

Your presidential chain (which includes me, President-Elect Mary Gromko, and Retiring President Juliana Texley), Board and Council, are very grateful for the willingness of these members to join our team. We will work together to develop creative attitudes in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics for all our students. NSTA members who are interested in volunteering for a position on one of our committees, advisory boards, or review panels can find more information online. Not a member, but interested in shaping the direction of science education in the future? See all of our member benefits here.

Carolyn Hayes is the NSTA President, 2015-2016; follow her on Twitter at caahayes.

Carolyn Hayes is the NSTA President, 2015-2016; follow her on Twitter at caahayes.

New Committee/Advisory Board/Panel Members

College

Cindy Birkner

Sarah Lang

John Wiginton

Coordination

David Johnson

Linda Schoen Giddings

Andria Stammen

High School

Lauren Case

Courtney Leifert

Steven Wood

Informal

Ed Barker

Joy Kubarek

Brad Tanner

Middle Level

Justin Brosnahan

Melanie Canaday

Tiauna Washington

Multicultural

Lisa Ernst

Sandra Osorio

Darrell Walker

Preschool-Elementary

Patricia Paulson

Stephanie Selznick

Danae Wirth

Preservice

David Crowther

Bianca Deliberto

Cynthia Gardner

Carolyn Mohr

Kira Heeschen (Preservice Teacher Rep)

Elaine Scarvey (Preservice Teacher Rep)

NSTA Teacher Accreditation

Carole Lee

Starlin Weaver

Professional Development

Cherry Brewton

Brittany Head

Catherine Shelton

Research

Victor Sampson

Kristen Sumrall

Cathy Wissehr

Audit

Rene Carson

Awards

Mary Maddox

Sheila Smith

Pam Vaughan

Budget

Jean Tushie

Nominations

Elsa Bailey

Michelle Daml

Gerald Darling

Janice Koch

Barbara Morrow

Aerospace

Kathy Biernat

Jacqueline Pfeiffer

Taylor Planz

Conference

Monica Ellis

Development

Patty McGinnis

International

Kathryn Elkins

Faiza Abdul Qayyum

Antoinette Schlobohm

Investment

Steve Rich

Journal of College Science Teaching

Issam Abi-El-Mona

Elizabeth Allan

David Wojnowski

NSTA Reports

Aaron Eling

Suzan Locke

Derenda Marshall

Retired

Lloyd Barrow

Gary Koppelman

Carrie Launius

Marilyn Richardson

Science and Children

Judy Clephane

Sherry Harrington

Laura Maricle

Science Matters

Ann Huber

Susan Tate

Jeni Williams

Science Safety

Patricia Hillyer

Rick Rutland

Rebecca Stanfield

Mary Loesing (reappointed)

Kathleen Brooks (extended)

Science Scope

Mary Pella-Donnelly

Heather Janes

Mary Elizabeth McKnight

Special Needs

Carol Cao

Meribeth Lowe

Sheryl Sotelo

Technology

Donna Cole

Kristen Kohli

Mijana Lockard

TST

Brian Bollone

Geri Granger

Traci Richardson

Urban Science

Brandon Gillette

Alton Lee

EllaJay Parfitt

CBC

Genet Mehari

Len Sharp

Trupti Vora

New Science Teachers

Alaina Anderson

Rebecca Gibson

Sumi Hagiwara

Shell

Peggy Carlisle

Carrie Lanius

Kristen Poindexter

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

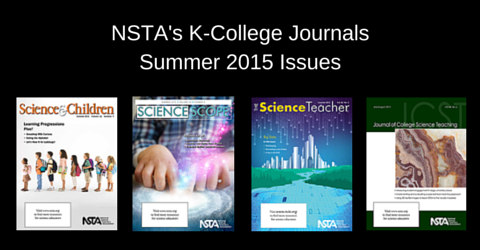

NSTA’s K-College July 2015 Science Education Journals Online

By Lauren Jonas, NSTA Assistant Executive Director

Posted on 2015-07-05

Varied ways to use instructional sequences that support valid learning, making science accessible to all students, big data, and identifying textbooks or other reading materials that are written at the appropriate reading grade levels—these are the themes of the Summer 2015 journal articles from the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA). Browse through the thought-provoking selections below and learn more about families learning together, integrated STEM units, harvesting data, peer-led team learning, and other important topics in K–College science education.

Science and Children

How much easier it would be, how much more learning would occur, and how much time we would save if all students brought the same background knowledge and skills to what they are learning? This issue of Science and Children employs the Next Generation of Science Standards (NGSS) to show the variety of ways in which you can use an instructional sequence that supports valid learning.

How much easier it would be, how much more learning would occur, and how much time we would save if all students brought the same background knowledge and skills to what they are learning? This issue of Science and Children employs the Next Generation of Science Standards (NGSS) to show the variety of ways in which you can use an instructional sequence that supports valid learning.

Featured articles (please note, only those marked “free” are available to nonmembers without a fee):

- Free – Dig Into Fossils!

- Eating the Alphabet

- Free – Editor’s Note: Identifying a Progression of Learning

- Families Learning Together

- Free – Guest Editorial: The Next Generation Science Standards: Where Are We Now and What Have We Learned?

- Let’s Hear It for Ladybugs!

- Smashing Milk Cartons

- Full Table of Contents

Science Scope

Making science accessible to all students should be the goal of every classroom science teacher. In this issue we share a variety of lessons you can use to overcome various socioeconomic, physical, and language barriers facing today’s students. We hope you can use these activities to help all of your students reach the stars.

Making science accessible to all students should be the goal of every classroom science teacher. In this issue we share a variety of lessons you can use to overcome various socioeconomic, physical, and language barriers facing today’s students. We hope you can use these activities to help all of your students reach the stars.

Featured articles (please note, only those marked “free” are available to nonmembers without a fee):

- Artificial Floating Islands: An Integrated STEM Unit

- Collaborative Concept Maps: A Voice for All Science Learners

- Free – Editor’s Roundtable: Charting a Course Toward NGSS Alignment

- Engineering Progressions in the NGSS Diversity and Equity Case Studies

- Science Meets Engineering: Applying the Design Process to Monitor Leatherback Turtle Hatchlings

- Supporting Science Access for All Students: Using Content Enhancements to Create Pathways to the Big Ideas

- The Fish Weir: A Culturally Relevant STEM Activity

- Free – The Next Generation Science Standards: Where Are We Now and What Have We Learned?

- Touching the Stars: Making Astronomy Accessible for Students With Visual Impairments

- Full Table of Contents

The Science Teacher

Ever-increasing volumes of information from sensors, satellites, cell phones, telescopes, global information systems, and social media provide unprecedented opportunities for scientists, citizens, and students to investigate complex systems. Scientific progress doesn’t result from simply accumulating data. But there’s no doubt that big data is revolutionizing fields as diverse as astronomy, marketing, genomics, climate science, oceanography, social science, and health care. Big data has the potential to transform science teaching and learning as well. Our students can engage in the higher-order thinking involved in analyzing and interpreting large science data sets and designing their own inquiries to discover patterns and meaning in mountains of accessible data, as authors in this issue of The Science Teacher illustrate.

Ever-increasing volumes of information from sensors, satellites, cell phones, telescopes, global information systems, and social media provide unprecedented opportunities for scientists, citizens, and students to investigate complex systems. Scientific progress doesn’t result from simply accumulating data. But there’s no doubt that big data is revolutionizing fields as diverse as astronomy, marketing, genomics, climate science, oceanography, social science, and health care. Big data has the potential to transform science teaching and learning as well. Our students can engage in the higher-order thinking involved in analyzing and interpreting large science data sets and designing their own inquiries to discover patterns and meaning in mountains of accessible data, as authors in this issue of The Science Teacher illustrate.

YouTube fans, watch high school science teacher and TST Field Editor, Steve Metz, introduce this month’s issue.

Featured articles (please note, only those marked “free” are available to nonmembers without a fee):

- Day in the Field

- Free – Editor’s Corner: Big Data

- Harvesting a Sea of Data

- Playing With Science

- Free – The Next Generation Science Standards: Where Are We Now and What Have We Learned?

- Free – Thinking Big

- Full Table of Contents

Journal of College Science Teaching

How do you handle the challenge of identifying textbooks or other reading materials that are written at the appropriate reading grade level yet still offer the desired content? See “Assessing the Readability of Geoscience Textbooks” to learn how one author assessed the readability of various materials to ensure that the text was not too challenging for students to comprehend. The Case Study article offers a detailed, step-by-step guide to helping students (and instructors) write case studies that are creative, well researched, and useful for teaching a topic to others. And don’t miss the Research and Teaching article that explores the effectiveness of incorporating 3D tactile images critical for learning STEM into entry-level lab courses for both sighted and vision-impaired students.

How do you handle the challenge of identifying textbooks or other reading materials that are written at the appropriate reading grade level yet still offer the desired content? See “Assessing the Readability of Geoscience Textbooks” to learn how one author assessed the readability of various materials to ensure that the text was not too challenging for students to comprehend. The Case Study article offers a detailed, step-by-step guide to helping students (and instructors) write case studies that are creative, well researched, and useful for teaching a topic to others. And don’t miss the Research and Teaching article that explores the effectiveness of incorporating 3D tactile images critical for learning STEM into entry-level lab courses for both sighted and vision-impaired students.

Featured articles (please note, only those marked “free” are available to nonmembers without a fee):

- Free – Are “New Building” Learning Gains Sustainable?

- Assessing the Readability of Geoscience Textbooks, Laboratory Manuals, and Supplemental Materials

- Collaboration-Focused Workshop for Interdisciplinary, Inter-Institutional Teams of College Science Faculty

- Implementing and Evaluating a Peer-Led Team Learning Approach in Undergraduate Anatomy and Physiology

- Research and Teaching: A New Tool for Measuring Student Behavioral Engagement in Large University Classes

- Research and Teaching: Aligning Assessment to Instruction: Collaborative Group Testing in Large-Enrollment Science Classes

- Research and Teaching: Methods for Creating and Evaluating 3D Tactile Images to Teach STEM Courses to the Visually Impaired

- Targeted Courses in Inquiry Science for Future Elementary School Teachers

- Using Popular Text to Develop Inquiry Projects: Supporting Preservice Teachers’ Knowledge of Disciplinary Literacy

- Full Table of Contents

Get these journals in your mailbox as well as your inbox—become an NSTA member!

Follow NSTA

Our Most Popular NSTA Press Book Quotes

By Carole Hayward

Posted on 2015-07-02

For nearly two years, NSTA Press has been pinning quotes from its books to Pinterest. Our followers often repin these interesting, informative, and often inspirational quotes. These are the books that have garnered the most attention. Are you following us on Pinterest?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

For nearly two years, NSTA Press has been pinning quotes from its books to Pinterest. Our followers often repin these interesting, informative, and often inspirational quotes. These are the books that have garnered the most attention. Are you following us on Pinterest?

Three major features of “doing” science

By Robert Yager

Posted on 2015-07-02

NSTA has identified three major features of students who actually “Do” science. The first of these is Human explorations of the natural world. The second includes Explanations of the objects and events encountered. And the third requires Evidence to support the explanations proposed. These features should be incorporated in science teaching for all students to ensure that students experience the actual “Doing of Science!”

We want students (and teachers) around the world to experience science in every K-16 science classroom. If we’re doing it right, students will “question”, “think creatively”, and “gather evidence” continually to support the explanations. It is especially important that the validity of the explanations proposed be established. Such experiences with “science” are not typically taught to students by science teachers. All (both students and teachers) should share explanations and interpretations about objects and events which they themselves have encountered.

The use of textbooks, laboratory manuals, teacher lectures, and other quick fixes for teacher actions are all opposite examples of “doing” science. Evaluating what students merely remember and repeat individually and/or collectively does not result in real science learning. Students must formulate their own ideas, including minds-on experiences, to really understand all aspects of “doing” science.

G. G. Simpson explained the “doing of science” looks like this:

- Asking questions about the objects and events encountered;

- Formulating possible answers/explanations;

- Collecting evidence in nature to determine the validity of the explanations offered;

- Checking on other attempts made by other experts; and

- Sharing the solution(s) with others.

“Science” is not like art and drama where teachers admire and/or criticize the performances of their best students. “Science” starts with unknowns and then seeking answers to explain them!

Robert E. Yager

Professor of Science Education

University of Iowa

NSTA has identified three major features of students who actually “Do” science. The first of these is Human explorations of the natural world. The second includes Explanations of the objects and events encountered. And the third requires Evidence to support the explanations proposed. These features should be incorporated in science teaching for all students to ensure that students experience the actual “Doing of Science!”

Exploring the properties of clay

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2015-07-01

Finding bits of clay pottery made and discarded by people hundreds of years ago reminds me of how this useful material can be a valuable addition to a preschooler’s experience. Of the earth but not commonly found on playgrounds, clay could be regularly provided in a bin for sensory experiences or building material. It can be made into almost anything! I wrote about the process we used to introduce clay work in the Summer 2015 issue of Science and Children.

Finding bits of clay pottery made and discarded by people hundreds of years ago reminds me of how this useful material can be a valuable addition to a preschooler’s experience. Of the earth but not commonly found on playgrounds, clay could be regularly provided in a bin for sensory experiences or building material. It can be made into almost anything! I wrote about the process we used to introduce clay work in the Summer 2015 issue of Science and Children.

When children first encountered the clay indoors at a table, they were immediately drawn to this new material. After working with the clay, children realized that it stuck to their hands, and some began to purposefully coat their hands in a way they could never do with playdough. This same property made other children avoid the clay. Having a system to rinse off hands in a tub of water after clay work, and before washing them, helped children feel comfortable with the “stickiness” of clay, and saved the excess clay so it didn’t get washed into the drains. Because the children were so used to the feel and texture of playdough, it took some time for them to capably shape it into balls, snakes and castles.

When children first encountered the clay indoors at a table, they were immediately drawn to this new material. After working with the clay, children realized that it stuck to their hands, and some began to purposefully coat their hands in a way they could never do with playdough. This same property made other children avoid the clay. Having a system to rinse off hands in a tub of water after clay work, and before washing them, helped children feel comfortable with the “stickiness” of clay, and saved the excess clay so it didn’t get washed into the drains. Because the children were so used to the feel and texture of playdough, it took some time for them to capably shape it into balls, snakes and castles.

We made sticks available and the children incorporated the two materials. It was interesting that the class of older twos and the class of fours both approached the materials in the same way–sticks stuck into a base of clay. In the fall I will introduce the clay on the playground and see what the children do with it as they have even more time to learn its many uses. It can be used to model 3D forms, draw on its surface, and paint with in a watered down form. Will they incorporate sticks and leaves, decorate it with pinecones or knead in sand to create a new building material?

Finding bits of clay pottery made and discarded by people hundreds of years ago reminds me of how this useful material can be a valuable addition to a preschooler’s experience. Of the earth but not commonly found on playgrounds, clay could be regularly provided in a bin for sensory experiences or building material.

Finding bits of clay pottery made and discarded by people hundreds of years ago reminds me of how this useful material can be a valuable addition to a preschooler’s experience. Of the earth but not commonly found on playgrounds, clay could be regularly provided in a bin for sensory experiences or building material.