New year, new format for The STEM Classroom

By Becky Stewart

Posted on 2015-01-20

Welcome to my new blog! The old STEM Classroom e-newsletter has gotten a makeover and become part of the new monthly Science and the STEM Classroom. As part of the redesign, I’m getting a chance to hone my skill at blogging in WordPress. A blog offers some different functionality and increased opportunities for sharing and connecting. I’m looking forward to the opportunity to learn more about formatting and how to embed images in WordPress.

Welcome to my new blog! The old STEM Classroom e-newsletter has gotten a makeover and become part of the new monthly Science and the STEM Classroom. As part of the redesign, I’m getting a chance to hone my skill at blogging in WordPress. A blog offers some different functionality and increased opportunities for sharing and connecting. I’m looking forward to the opportunity to learn more about formatting and how to embed images in WordPress.

I am, of course, a bit late to the party. Blogging as an educational tool has been a thing for a good 10 years now. Many of today’s classroom courses have a blog component, thanks to the ubiquity of Blackboard in higher education and other learning management systems like the open-source option, Moodle, and Edmodo, which is aimed at primary and secondary school audiences. The best part about this blogging opportunity, though, is that I’ll learn to do more advanced coding in HTML. This month, I’ll give you some ideas for incorporating coding or its fruits in your classroom.

Science Connection: Effective Science Communication

I’ve written before about the importance of communicating science for lay audiences. One of the challenges in attracting new students to scientific fields is that so much of what is written about new and exciting science is obscured by jargon. This is beginning to change, and a number of science communicators have dedicated themselves to ensuring that news about good science gets the wider attention it deserves. Some of those communicators, like Joe Hanson, are using the Internet to host several different channels of communication. Hanson has a Facebook page, Twitter feed, YouTube channel, and a blog. If you don’t already keep a list of science communication resources in your classroom, you can start with these.

Blogs

Any of the blogs from Discover magazine or the blogs at SciLogs (and there are lots of them).

On Twitter

A search for science communicator will bring up lots of results. The writers of the Discover or SciLogs blogs are good places to start.

YouTube Channels

This list is by no means comprehensive, and I encourage you to explore via the links posted at the mentioned sites as well as in the subject areas that most fit your own interests.

Technology Connection: Coding

You’ve probably heard some of the debate about coding and whether computer programming classes should have a place in every school. The proponents of adding this subject in school argue that learning a programming language will teach students problem solving skills. It also helps them move from simply consuming content to being able to create it, which is an essential human trait that we risk limiting access to as the world becomes more digital and less analog. Of course, learning a programming language can be challenging, and may not be necessary for everyone.

The debate about the place of coding in schools will continue. But if you’re looking for a new skill to add to your repertoire in the new year, there are a number of ways you can learn some basic coding.

If you want some background about why knowing a little bit about coding is useful, read this article about how the web works. The Internet is often the first source of information for today’s students, if not necessarily their teachers. It’s always easier to use something if you know more about how it works. It’s a good bet that your students’ workplaces will have a significant web presence. Some of those workplaces, like Etsy, even encourage employees to learn more about how their websites work. In addition, coding is taking a growing role in data visualization in the sciences. For some background on the R data visualization and statistical analysis package, read this article.

Engineering Connection: How Engineers Work

As proof that the Internet is changing the way everyone works, a compelling argument for why engineers should learn to code is presented in this blog post. Knowledge of some basic coding can help engineers work more efficiently with their data.

If you’d like more resources for inspiring your students to study engineering, a number of entertaining engineering blogs are highlighted in this article. A list of 10 YouTube channels every engineer must see can be found here.

Math Connection: New Ways of Doing Math

The recent controversy surrounding the release of Sony Pictures’ The Interview led to a good example of algebra in action. The studio reported $15 million in revenue from the first four days of online sales and rentals, from a total of 2 million transactions. The initial New York Times article about the release stated that the studio did not report how many of the transactions were $6 rentals versus $15 sales, but then the Internet took over.

The percentage of students who require remedial math courses in college before they can take the math sequences required for graduation is an issue of concern. A number of community colleges are piloting the Pathways math sequences from the Carnegie Foundation. These courses teach essential math concepts for students who do not plan to major in STEM fields in college, without getting too heavily involved in algebra, which particularly in community colleges has a very high failure rate.

Math Blogs (again, not a comprehensive list)

Don’t Miss Out

The ITEEA Annual Conference, March 26–28, 2015, Milwaukee, WI Philadelphia Science Festival, April 24–May 2, 2015, Philadelphia, PA

If your organization is planning a STEM event and you’d like a notice to appear in this blog, please email the editor, Becky Stewart, at STEMClass@nsta.org. I’d love to hear from you.

Produced by the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA), The STEM Classroom is written by science writer Becky Stewart as a forum for ideas and resources that middle and high school teachers need to support science, technology, engineering, and math curricula. Fans of the old version of The STEM Classroom e-newsletter can find the archives here.

Follow NSTA

| |

|

|

|

Welcome to my new blog! The old STEM Classroom e-newsletter has gotten a makeover and become part of the new monthly Science and the STEM Classroom.

Welcome to my new blog! The old STEM Classroom e-newsletter has gotten a makeover and become part of the new monthly Science and the STEM Classroom.

Senate releases draft of No Child Left Behind legislation

By Guest Blogger

Posted on 2015-01-19

Last week Sen. Lamar Alexander, chairman of the Senate Health Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee released a 400-page discussion draft proposal which would rewrite the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, or No Child Left Behind.

Last week Sen. Lamar Alexander, chairman of the Senate Health Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee released a 400-page discussion draft proposal which would rewrite the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, or No Child Left Behind.

The draft language would provide states with flexibility to decide accountability (testing) issues, and it consolidates most of the Department of Education’s K–12 programs for Teacher Quality, including the Math and Science Partnership, into a single formula grant program.

Earlier this month Senator Alexander said he wanted to get a bill to mark up by the end of February. The ensuring work between the Republican and Democratic education leaders in the Senate has led many in Washington, DC to believe this is a strong and viable attempt to come to consensus and rewrite the federal education law.

But many differences still remain. Senator Patti Murray, ranking Democrat on the HELP Committee, has signaled her priorities for the bill are to reduce testing and expand preschool. In a speech last week on ESEA education, Secretary Arne Duncan said he also wants increased funding for preschool, continued teacher evaluations, and targeted resources to the lowest-performing schools.

The STEM Education Coalition (which NSTA chairs) is calling on Congress to include a requirement that states continue to assess student performance in mathematics and science and that STEM education–related activities be given high priority in major education programs at the U.S. Department of Education (DoEd), especially those focused on teacher quality and professional development.

Stay tuned, much more ahead in coming weeks.

Jodi Peterson is Assistant Executive Director of Legislative Affairs for the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) and Chair of the STEM Education Coalition. e-mail Jodi at jpeterson@nsta.org; follower her on Twitter at @stemedadvocate.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

| |

|

|

|

NSTA and ASE: creating pathways to better international cooperation in science education

By Juliana Texley

Posted on 2015-01-19

They say the world is flat … and so it often seems. Cross the ocean by plane, or travel far from home by train or car…sit down for coffee with other teachers…and the issues are almost always the same. We find much in common wherever we go. And I found this to be true recently when I attended the annual meeting of the Association for Science Education (ASE) at the University of Reading, in England (NSTA’s counterpart in the UK).

They say the world is flat … and so it often seems. Cross the ocean by plane, or travel far from home by train or car…sit down for coffee with other teachers…and the issues are almost always the same. We find much in common wherever we go. And I found this to be true recently when I attended the annual meeting of the Association for Science Education (ASE) at the University of Reading, in England (NSTA’s counterpart in the UK).

NSTA’s collaboration with the Association for Science Education has a long history. The Patron of the Association is HRH Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, and it traces its origins back to 1900. The first Annual Meeting was held in January 1901, which then led to the formation of the Association of Public School Science Masters. Incorporated by Royal Charter in October 2004, the ASE operates as a Registered Charity. (By comparison, NSTA dates back to 1944.) ASE’s governance structure is a bit different. Each year a high-profile scientist or educator is appointed President and serves as spokesman for the organization. This year it’s Professor Sir David Bell, chancellor of University of Reading in the UK. On his first day “on the job” he made a major address to the ASE conference and did a radio interview about the importance of science education. The operational governance of ASE is managed by Chair Chris Harrison and Executive Director Shaun Reason. (Chris is a science education researcher and professor.)

So much for the differences; the rest is much the same. On the first day of my visit, I sat with a teacher from Finland who was looking for ways to help his bilingual immigrant students (mostly Somalian) integrate quickly. Next morning I did a workshop on “square pegs,” diverse learners who don’t seem to fit into regular classroom routines and how to structure lessons to make them successful. The attendees each had their own “square pegs” and shared many innovative solutions. NSTA’s retiring president Bill Badders was there, too, and did a workshop on how to integrate literacy seamlessly into an inquiry lesson on earthworms. Again, everyone found it relevant and the discussions were very energetic. I attended sessions on integrating science and social studies (geography) and assessment, ideas that would translate to any country’s teachers in any language. Even the exhibit hall had lots of material that merited importing, like science in Europe in the Middle Ages (much from the Islamic areas of Spain), and the greatest 3D exploration of cell biology yet.

So much for the differences; the rest is much the same. On the first day of my visit, I sat with a teacher from Finland who was looking for ways to help his bilingual immigrant students (mostly Somalian) integrate quickly. Next morning I did a workshop on “square pegs,” diverse learners who don’t seem to fit into regular classroom routines and how to structure lessons to make them successful. The attendees each had their own “square pegs” and shared many innovative solutions. NSTA’s retiring president Bill Badders was there, too, and did a workshop on how to integrate literacy seamlessly into an inquiry lesson on earthworms. Again, everyone found it relevant and the discussions were very energetic. I attended sessions on integrating science and social studies (geography) and assessment, ideas that would translate to any country’s teachers in any language. Even the exhibit hall had lots of material that merited importing, like science in Europe in the Middle Ages (much from the Islamic areas of Spain), and the greatest 3D exploration of cell biology yet.

There were some differences in emphasis, of course. Assessment is a high-priority issue there as here, and there were many sessions on the topic. But because of the smaller scale (and perhaps less litigious environment), there were more initiatives in performance and multi-factorial assessment programs discussed. And because the current assessments are very familiar to educators, it was common to learn about how a certain experience could increase success on a certain component of a test.

The growing emphasis on early childhood education here has already been embedded into science education in the UK, with many creative ideas. And of course, our national goals are changing at a much more rapid pace with the inspiration of the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS)—a topic that almost every participant wanted to learn more about. Change is occurring in England, Scotland,and Wales as well, but perhaps at a slightly slower pace that might seem more manageable to the average attendee.

The meeting also provided opportunities for me to talk to the ASE staff about organizational issues. They share the challenge of getting pre-service teachers to stay involved once they are hit with the heavy load of their first few years of teaching. The meeting featured a great forum where beginning teachers could make 10-minute presentations of their favorite lessons rather than commit to a full=hour session; this was one of the most popular areas of the exhibit hall and it seemed “a good time was had by all.”

In the past many NSTA members have associated international efforts with tours. Visiting schools and teachers is always informative and enriches our perspective on what we do at home. But we can go much further. Our International Committee does far more than that, beginning with a full day of discussions at each national conference. At ASE we discussed possible projects through which we might combine web resources in a convenient and easy-to-access portal, create international discussion forums on very specific topics like climate change education, and perhaps exchange publications. Citizen Science initiatives might also enable us to facilitate for young investigators the comparison of methods and ways of thinking, and these insights could help us adapt our own classroom curricula to an increasingly diverse student body. (Do you have ideas? Send them to Juliana_texley@nsta.org and they will be included in a Board discussion in the near future.)

In common conversation, the term “flat” is often equated with something that is boring or lacks effervescence. But not in this case! A “flat” world is one with endless opportunities. To create valuable pathways to better international cooperation in science education, we don’t have to cross high hurdles. Our common teaching instincts provide the sign posts to guide us toward productive collaborations.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

| |

|

|

|

January journals and SciLinks

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2015-01-17

One of the perks of being an NSTA member is having access to all of the journals online. Regardless of the grade level you teach, the journals have ideas for authentic activities and investigations that can be used, adapted, or extended for different levels of student interest and experience. Most are aligned with the NGSS.

This month, the article EQuIP-ped for Success appears in all three journals, describing a rubric with criteria on which to evaluate lessons and units and their alignment with the NGSS.

Science & Children: Systems and System Models

Science & Children: Systems and System Models

Most of our students are familiar with the solar and metric “systems,” but any interaction of two or more things can be considered a system, and the resulting system can help us understand phenomena. This issue explores systems and the models used to understand them. Bill Robertson’s Science 101 column–How Should We Use the Concept of Systems?—is a good summary of the topic. And here are some SciLinks that provide content information and suggestions for additional activities and investigations related to this month’s featured articles:

- The Early Years: Exploring Systems [Systems]

- Formative Assessment Probes: Ice Cubes in a Bag [States of Matter]

- Teaching Through Trade Books: What’s the Big Idea About Bees? [Honey Bees, Pollination]

- Design in the Watershed [Watersheds, Water Quality]

- Printing the Playground [Engineering Structures]

- Virtual Modeling [Models]

- In the Watery World [Rivers and Streams, Water Quality, Invertebrates]

- Modeling Change With Clay [Landforms, Changes in the Earth’s Surface]

- Engineering Encounters: A System of Systems [Systems]

- Methods and Strategies: The Future of Farming [Plants as Food, Plant Growth]

Science Scope: Human Impacts on Earth Systems

Science Scope: Human Impacts on Earth Systems

The featured articles explore the ever-threatening human impact on Earth systems. Get some ideas for student projects and investigations on the topic. Here are some SciLinks that provide content information and suggestions for additional activities and investigations related to this month’s featured articles:

- Aliens Invade and Drop Off Litter [Invasive Species]

- The Human Impact on Earthquakes: Natural Fracturing Versus Fracking [Earthquakes, Tectonic Plates, Predicting Earthquakes, Earthquake Measurement]

- Life With Limited Resources [Duckweed, Sustainable Development, Deforestation, Food Webs]

- No Space? Little Money? No Garden? Not So Fast! [Composting, Sustainable Agriculture]

- Plotting Plants [Invasive Species, Taxonomy]

- Tried and True: A Water Cycle of Many Paths [Water Cycle]

The Science Teacher: Project-Based Science

The Science Teacher: Project-Based Science

Projects have come a long way from the days of gumdrop replicas of the atom! Working on projects provides students with ways of connecting and applying the content, practices, and concepts they are learning. The article Project-Based Science leads off this discussion. Here are some SciLinks that provide content information and suggestions for additional activities and investigations related to this month’s featured articles:

- The Green Room: Symbiotic Relationships [Symbiosis, Parasitism and Mutualism]

- Health Wise: Pardon me? Helping Students Avoid Noise-Induced Hearing Loss [Noise Pollution, Hearing]

- Near-Space Science: A Ballooning project to engage students with space beyond the big screen [Gas Laws, Kinetic Theory, Air Pollution]

- Global Warning [Climate Change, Global Warming]

- Treating Pompe Disease [Dominant and Recessive Traits, Enzymes]

- The Community Connection [Water Quality, Watersheds, Eutrophication]

One of the perks of being an NSTA member is having access to all of the journals online. Regardless of the grade level you teach, the journals have ideas for authentic activities and investigations that can be used, adapted, or extended for different levels of student interest and experience. Most are aligned with the NGSS.

The Next Generation Science Standards: a transformational opportunity

By Guest Blogger

Posted on 2015-01-15

The Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) and A Framework for K–12 Science Education articulate a beautiful vision for students. The overarching goal of the standards is a coherent and rigorous science education for all students, enabling them to be critical consumers of science and attain the scientific literacy necessary to be informed citizens able to engage in public discourse and decision making on issues of science, engineering, and technology. For those who are so inspired, attaining proficiency in the standards provides students with the foundation needed to pursue STEM careers (a much-needed cohort in our society). Whereas the vision is clear, there is no single path teachers can follow to implement the Next Generation Science Standards. K–12 teachers who want to play a central role in transforming science teaching and learning need guidance in creating paths along which they can translate the NGSS into strong curricula and inspired instruction.

The Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) and A Framework for K–12 Science Education articulate a beautiful vision for students. The overarching goal of the standards is a coherent and rigorous science education for all students, enabling them to be critical consumers of science and attain the scientific literacy necessary to be informed citizens able to engage in public discourse and decision making on issues of science, engineering, and technology. For those who are so inspired, attaining proficiency in the standards provides students with the foundation needed to pursue STEM careers (a much-needed cohort in our society). Whereas the vision is clear, there is no single path teachers can follow to implement the Next Generation Science Standards. K–12 teachers who want to play a central role in transforming science teaching and learning need guidance in creating paths along which they can translate the NGSS into strong curricula and inspired instruction.

So, how can teachers build aligned NGSS curricula and instruction? Through individual reflection and productive struggle; conversation and collaboration with science educators nationwide; and partnerships with national, state, and local supporters, teachers can develop and implement a shared vision for classroom teaching and learning in science.

Reflection

Groups of teachers all over the United States are finding the path to NGSS less daunting when they actively engage in adult learning through reflection on how their new approaches to science teaching are working and are mindful when reviewing resources for implementation. There is always that temptation to look for the easy answers about “How to do the NGSS.” But following someone else’s plans without thoughtful reflection, analysis, and debate will not enable us to reach our own understanding. Without our own deep understanding, we cannot truly shift our classrooms in a sustained way to the deep thinking and critical perspectives required in NGSS. As authors Eric Brunsell, Deb M. Kneser, and Kevin J. Niemi so effectively state in one of my favorite new resources, Introducing Teachers and Administrators to the NGSS, “the NGSS represents an evolution of our understanding of the standards, not a complete break with the past.”

Groups of teachers all over the United States are finding the path to NGSS less daunting when they actively engage in adult learning through reflection on how their new approaches to science teaching are working and are mindful when reviewing resources for implementation. There is always that temptation to look for the easy answers about “How to do the NGSS.” But following someone else’s plans without thoughtful reflection, analysis, and debate will not enable us to reach our own understanding. Without our own deep understanding, we cannot truly shift our classrooms in a sustained way to the deep thinking and critical perspectives required in NGSS. As authors Eric Brunsell, Deb M. Kneser, and Kevin J. Niemi so effectively state in one of my favorite new resources, Introducing Teachers and Administrators to the NGSS, “the NGSS represents an evolution of our understanding of the standards, not a complete break with the past.”

If we develop a deep understanding of the NGSS and build our capacity as teachers to coach students toward independent thinking and lifelong learning, we will be able to use many of our own resources by making revisions and shifts in design, and we will be able to develop our own skills as critical consumers of new resources. The productive struggle of “figuring it out” for ourselves with support from others is what leads to deep understanding. We already know this to be true for our students, so shouldn’t we apply the same principles to our own learning? What could we build together if we applied this thinking to ourselves when it comes to NGSS?

Conversation and Collaboration

The NGSS is an opportunity for us to collaborate and have conversations around a national common language. One place I like to find support for my own reflection is the NGSSblogs Project. We started this to elevate the collective conversation, so teachers can build paths to NGSS implementation resulting in empowerment for both teachers and students. Just as we witness in our own classrooms, discourse moves understanding forward. I urge you to share your NGSS experiences, have conversations with the teacher down the hall, in the next district, on the other side of the state. Collaborate with those teachers by sharing your best lesson and work together to braid it into the NGSS. Learn from each other and together. The reflection required for sharing powers your own growth while making your reflections public moves the thinking and learning of others. Imagine the resources we could compile if teachers shared what was working (and not working) with NGSS implementation in their own classrooms? By building together, we can assemble an ever-evolving resource bank of NGSS support. Here are some opportunities for conversation, collaboration, and sharing:

The NGSS is an opportunity for us to collaborate and have conversations around a national common language. One place I like to find support for my own reflection is the NGSSblogs Project. We started this to elevate the collective conversation, so teachers can build paths to NGSS implementation resulting in empowerment for both teachers and students. Just as we witness in our own classrooms, discourse moves understanding forward. I urge you to share your NGSS experiences, have conversations with the teacher down the hall, in the next district, on the other side of the state. Collaborate with those teachers by sharing your best lesson and work together to braid it into the NGSS. Learn from each other and together. The reflection required for sharing powers your own growth while making your reflections public moves the thinking and learning of others. Imagine the resources we could compile if teachers shared what was working (and not working) with NGSS implementation in their own classrooms? By building together, we can assemble an ever-evolving resource bank of NGSS support. Here are some opportunities for conversation, collaboration, and sharing:

- NGSS Multi Tools Online Community of Teachers

- NGSSPeer Learning Network on Google Plus

- #NGSSchat on Twitter

Partnerships with Classroom Supporters

If the reflection and collaboration supports our deep understanding of the NGSS and opportunities to learn and share together, how can we collectively determine a sense of what is “good enough”? How can we ensure we have quality resources, models, and unit progressions for NGSS teaching and learning? Through partnerships and community support, we can work together to create models of great classroom teaching and learning. The National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) has been a leader in supporting teachers first in understanding the Next Generation Science Standards themselves and then in understanding how to use the NGSS to transform their science classrooms.

To help science teachers, NSTA has created the NGSS@NSTA Hub—a one-stop shop for a multitude of resources for teachers to design NGSS instruction for classroom learning. Resources include articles, webinars, videos, models—and coming soon, an interactive database to support teacher collaboration. Tools and resources like these provide support for teachers to collaborate and build instruction and curriculum.

To help science teachers, NSTA has created the NGSS@NSTA Hub—a one-stop shop for a multitude of resources for teachers to design NGSS instruction for classroom learning. Resources include articles, webinars, videos, models—and coming soon, an interactive database to support teacher collaboration. Tools and resources like these provide support for teachers to collaborate and build instruction and curriculum.

Another national supporter, Achieve, Inc., has facilitated work among the 26 lead states in developing the Next Generation Science Standards from the beginning. They continue to support teachers by providing resources and guidance during NGSS implementation. The EQuIP rubric developed by Achieve in a partnership with NSTA, for example, is a tool for determining how closely instructional materials align with the NGSS. An excellent overview on how to use the EQuIP rubric was recently written and gives great advice on How to Select and Design Materials that Align to the Next Generation Science Standards.

Another set of useful tools from Achieve are Evidence Statements. They are a sort of a way to do backwards math—they allow you to visualize the incremental captures of student learning on the path to demonstrating proficiency in performance expectations (PEs). They identify what your lesson is building toward and what still needs to be covered. They provide examples of 3D learning with details on what students should know and be able to do to meet performance expectations. The high school evidence statements have just been released, and middle school and elementary evidence statements are coming soon.

Equipped with all this information and resources, I urge science teachers to remember that they themselves are the most important part of the picture. To reimagine science education, we need more than a set of standards that capture a vision. Teachers are the catalysts for transforming science education; teachers have the practical experience and the day-to-day connections with students to make this happen. National partners like NSTA and Achieve are ready to support us. It is the work of classroom teachers and those who support classroom learning that makes the vision come to fruition. Please become part of the work of building the kind of classroom experience that originally inspired us to become teachers—make your classroom a place of discovery and wonder that leads to investigating the world and building students understanding of the world. The NGSS gives us an opportunity to share our voice, passion, and gifts on a state and national level to help transform science education. What can you contribute to transform science classrooms to support science literacy so we can ensure those we teach today are ready for tomorrow?

Visit www.NGSSPLN.com for more information about a virtual community that is powered by teachers for teachers and allows you to share your talents by becoming part of the conversation.

Tricia Shelton is a High Science Teacher and Teacher Leader with a BS in Biology and MA in Teaching, who has worked for 19 years in Kentucky driven by a passion to help students develop critical and creative thinking skills. Tricia is a 2014 NSTA Distinguished Teaching Award winner for her contributions to and demonstrated excellence in Science Teaching. As a Professional Learning Facilitator and NGSS Implementation Team Leader, Tricia has worked with educators across the United States to develop Best Practices in the Science and Engineering classroom through conference presentations, webinars, coordinating and co- moderating #NGSSchat on Twitter, and virtual and face to face PLC work. Tricia’s current Professional Learning Facilitation includes work around the Next Generation Science Standards and helping STEM students develop the 21st Century Skills of critical and creative thinking, collaboration and communication (including Social media and Video) and Project-Based Learning. Since 2011, she has conducted action research in her classroom to develop effective and accessible instructional and assessment strategies incorporating Best Practice in the STEM classroom, including work for the Marzano Research Laboratory. Through a partnership with BenchFly, the premier science video production platform, she works with CEO, Dr. Alan Marnett, to reinvent scientific education and communication with video. Find Shelton on Twitter @TdiShelton.

Tricia Shelton is a High Science Teacher and Teacher Leader with a BS in Biology and MA in Teaching, who has worked for 19 years in Kentucky driven by a passion to help students develop critical and creative thinking skills. Tricia is a 2014 NSTA Distinguished Teaching Award winner for her contributions to and demonstrated excellence in Science Teaching. As a Professional Learning Facilitator and NGSS Implementation Team Leader, Tricia has worked with educators across the United States to develop Best Practices in the Science and Engineering classroom through conference presentations, webinars, coordinating and co- moderating #NGSSchat on Twitter, and virtual and face to face PLC work. Tricia’s current Professional Learning Facilitation includes work around the Next Generation Science Standards and helping STEM students develop the 21st Century Skills of critical and creative thinking, collaboration and communication (including Social media and Video) and Project-Based Learning. Since 2011, she has conducted action research in her classroom to develop effective and accessible instructional and assessment strategies incorporating Best Practice in the STEM classroom, including work for the Marzano Research Laboratory. Through a partnership with BenchFly, the premier science video production platform, she works with CEO, Dr. Alan Marnett, to reinvent scientific education and communication with video. Find Shelton on Twitter @TdiShelton.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

| |

|

|

|

The Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) and A Framework for K–12 Science Education articulate a beautiful vision for students.

The Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) and A Framework for K–12 Science Education articulate a beautiful vision for students.

Supplementing a budget decrease

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2015-01-14

Our principal just informed us that the science department budget will be decreased for next year. It’s already bare bones, so my colleagues and I are interested in finding other funding sources such as grants. What do we need to know to get started? — G., Oregon

Our principal just informed us that the science department budget will be decreased for next year. It’s already bare bones, so my colleagues and I are interested in finding other funding sources such as grants. What do we need to know to get started? — G., Oregon

In a perfect world, schools and teachers would all be funded adequately to provide the highest quality education for our students. As we wait for this to happen, you won’t be the only one looking for external funds to supplement a shrinking budget, and many agencies and organizations are themselves facing reduced resources.

You and your colleagues should discuss your needs and make some decisions as you begin the process. Your needs may include “everything,” so you should prioritize them into categories such as equipment, safety, instructional materials, professional development (including conferences), field trips, technology, and more. Discuss your needs assessment and how meeting those needs will improve student learning. Very few organizations or agencies will write blank checks, so this will help you match your needs with the missions of potential funders.

Differentiate between donations and grants. Donations are straightforward gifts, often very modest, with few strings attached, and often from more local organizations. Grants from large foundations or government agencies usually focus on projects for a particular purpose or audience and have requirements spelled out in a formal contract that must be signed by a school official. These requirements may include periodic progress reports, a formal evaluation component, student learning data, and an itemized budget. They are usually competitive. As a grantwriter, I found that the larger the grant, the more strings are attached.

Finding potential sources is another challenge.

If your school or district has a grantwriter or special projects coordinator, he or she may be able to assist. Check the high school yearbook or sports program to see what local businesses, individuals, or agencies are willing to support the schools through donations. Some parents may have ideas, too.

Colleagues on the NSTA e-mail lists have used Donors Choose to post online requests for project funds. You may want to look at the Science category to see how others are framing their requests.

Pore over a copy of the Science Teachers’ Grab Bag from NSTA Reports at your department meetings. This pull-out section includes Freebies for Science Teachers, What’s New from U.S. government sources (such as National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Geological Survey, and the National Science Foundation), and the In Your Pocket section (with information on grants, awards, fellowships, and competitions). You can refer to the Science Education Events and Programs calendar on the NSTA Website . NSTA conferences usually include sessions on grants, too.

If you decide to seek grant funding, you may have to define and refine your goals and needs to meet the grant description. Few grants will fund “brick and mortar” projects (construction or remodeling), basic items that schools/districts should provide such as classroom furniture or consumables (unless they are part of a more comprehensive project), or items that are not related to student learning.

Depending on the funding source, you may need to describe your needs more comprehensively. For example, “We want to include more hands-on learning in science to help students attain the Next Generation Science Standards” rather than simply stating “We need microscopes.” The broader statement puts the microscopes into a larger context and can be used in other proposals in a coordinated effort. Too often I’ve seen schools take a patchwork approach to grants, with no focus or master plan. Their projects may even be at cross-purposes and create extra work for teachers. If you align your proposed activities with the school/district/department strategic plan, you’ll have a coordinated rationale for further proposals.

Give yourself enough time to gather data, create a budget, assemble supporting documents (if required), and get the correct signatures on the forms (in some districts, requests must be sent or approved by the central office). Ask someone to proofread the proposal or request and follow any guidelines on length, formatting, the submission date, and the inclusion of extra materials.

If you receive a donation, be sure to write a thank-you letter (or better yet have the students write letters) and include photos of how the funds are affecting your classes.

Above all, don’t be discouraged if some of your proposals are “rejected.” (I have a whole collection of unfunded proposals.) You’ll have a lot of competition, but when your request is funded and your work pays off in good things for students, it’s a great feeling!

Photo: https://flic.kr/p/aFAEHR

System exploration in early childhood

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2015-01-14

When winter sets in, teachers set aside time in the schedule for children to remove and store their winter outwear. Such a variety of clothing systems appear! Coats and jackets with zippers, hoods, snaps and Velcro, mittens and gloves, hats that pull on or strap on, snow pants and overalls, scarves and boots! These items are the parts of the system that keeps children warm outside.

When winter sets in, teachers set aside time in the schedule for children to remove and store their winter outwear. Such a variety of clothing systems appear! Coats and jackets with zippers, hoods, snaps and Velcro, mittens and gloves, hats that pull on or strap on, snow pants and overalls, scarves and boots! These items are the parts of the system that keeps children warm outside.

Children master the skill of putting on and fastening these items over time as their fine motor skills develop and they have repeated opportunities to practice. Some children get undressed or dressed faster than their classmates. Instead of waiting, they can collect data. On a tally chart with pictures of each kind of clothing, they can make a tally mark for each item they observe. Some questions to investigate include, “Does the number of _____ change with changing weather?” “What kind of hat do children find easiest to put on? What kind of jacket do children find easiest to fasten? Which kinds of fastening do children prefer?

In the January 2015 issue of Science and Children, I wrote about children investigating coats as systems, examining the parts of various coats and measuring and recording data. What systems are the children in your program investigating?

In the January 2015 issue of Science and Children, I wrote about children investigating coats as systems, examining the parts of various coats and measuring and recording data. What systems are the children in your program investigating?

Although children experience a world where complex systems, such as atomic structure, operate, they may have not reached a developmental age where they understand these systems, forces and particles. We know this because researchers who investigate how children learn have discovered the age ranges when children can use their information to demonstrate or model these concepts (Michaels and others). Ready Set SCIENCE! (Michaels), particularly Chapter 3, discusses conceptual change in children’s thinking “as a result of instruction, experience, and maturation.” The authors state, “A key challenge for teachers is to build on students’ embodied knowledge and understanding of the world and to help them confront their misconceptions productively in order to develop new understanding” (pg 38).

Beginning with systems common in the lives of young children, early childhood educators can lay the foundation for later learning.

Michaels Sarah, and Andrew W. Shouse, Heidi A. Schweingruber. 2007. Ready, Set, Science!: Putting Research to Work in K-8 Science Classrooms. National Research Council

When winter sets in, teachers set aside time in the schedule for children to remove and store their winter outwear. Such a variety of clothing systems appear! Coats and jackets with zippers, hoods, snaps and Velcro, mittens and gloves, hats that pull on or strap on, snow pants and overalls, scarves and boots!

When winter sets in, teachers set aside time in the schedule for children to remove and store their winter outwear. Such a variety of clothing systems appear! Coats and jackets with zippers, hoods, snaps and Velcro, mittens and gloves, hats that pull on or strap on, snow pants and overalls, scarves and boots!

NSTA encourages West Virginia Board of Education to maintain fidelity to the Next Generation Science Standards

By Lauren Jonas, NSTA Assistant Executive Director

Posted on 2015-01-13

In a letter to the West Virginia Board of Education, the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) encourages the members of the Board to eliminate changes that were made to the Next Generation Content Standards and Objectives for Science in West Virginia Schools and revert back to the original published text. The West Virginia standards are based on the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), but changes were made to two performance expectations prior to adoption that do not reflect the intent of the original published NGSS document. The letter is below, and readers can download a copy as a pdf here.

January 13, 2015

West Virginia State Board of Education

1900 Kanawha Boulevard East

Charleston, WV 25305

Dear Members of the Board,

On behalf of the Board, Council, and 55,000 members of the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA), we strongly encourage you to eliminate changes that were made to the Next Generation Content Standards and Objectives for Science in West Virginia Schools prior to adoption in December and revert back to the original published text.

While West Virginia standards are based on the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), changes made to two performance expectations do not reflect the intent of the original published NGSS document or the Framework for K-12 Science Education.

The first change focuses on S.6.ESS.6. The original NGSS text states, “Ask questions to clarify evidence of the factors that have caused the rise in global temperatures over the past century,” but it was changed to read, “Ask questions to clarify evidence of the factors that have caused the rise and fall in global temperatures over the past century.” Adding the words “and fall” to S.6.ESS.6 risks confusion among students between the concepts of weather and climate.

The second change focuses on S.9.ESS.14. The original NGSS text states, “Analyze geoscience data and the results from global climate models to make an evidence-based forecast of the current rate of global or regional climate change and associated future impacts to Earth systems.” This text was replaced with, “Analyze geoscience data and the predictions made by computer climate models to assess their creditability for predicting future impacts on the Earth System.” The original wording asks students to use data and models to forecast the rate of climate change and future impacts on the Earth System. The revised wording asks students to assess the credibility of computer climate models to predict future impacts on the Earth System. This substantially changes the intent of this learning goal.

We are pleased that West Virginia state leaders have been at the forefront of developing the NGSS, and we will continue to support West Virginia science teachers as they bring high-quality science to all students. NSTA supports the NGSS the way the writers wrote it because it reflects the best research in science and on how students learn science. It is our hope that you will reverse the changes indicated above so as not to compromise the work of so many science and education experts, including many science teachers in West Virginia.

Sincerely,

Dr. David L. Evans

Executive Director

National Science Teachers Association

1840 Wilson Boulevard

Arlington, VA 22201

In a letter to the West Virginia Board of Education, the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) encourages the members of the Board to eliminate changes that were made to the Next Generation Content Standards and Objectives for Science in West Virginia Schools and revert back to the original published text.

The Pasco Wireless Dissolved Oxygen Probe VS. Winter Water

By Martin Horejsi

Posted on 2015-01-12

The power of a Bluetooth-connected Dissolved Oxygen probe is not only from the DO data, but the places the data can be collected, and the ways the data is presented. Over the holidays I took the Pasco wireless DO probe up in the mountains to generate some data and answer some questions. Since my winter/spring lesson plans will address the use of the probe outdoors, I needed to be more than a little familiar with it, and ensure that any limits or barriers of the technology were of my choosing or creation.

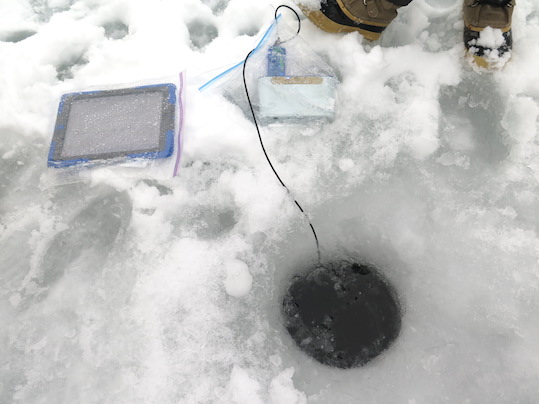

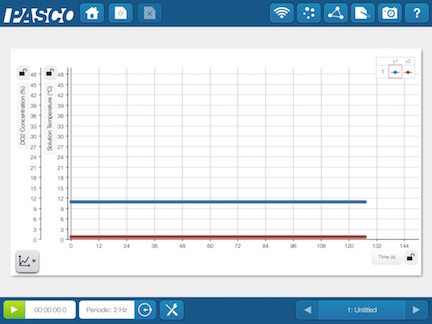

Three sites were chosen in which to measure the DO; a ice-covered pond, a small creek, and a rushing mountain stream. The DO probe connected to a Bluetooth transmitter called a SPARKlink Air to my iPad Air protected by both a UZBL Shockwave case and a Ziploc® bag.

Needless to say, the DO Probe, the Bluetooth basestation, and the iPad worked flawlessly. The biggest hurdle was simply trying to view the iPad screen though a soggy plastic bag and against the glare of a snow-covered landscape.

The durability of the Pasco DO probe was obvious, and while I don’t recommend any abuse, I do encourage data collectors to push the envelope.

As you can see in the pictures, the weather was a bit of a challenge, but nothing that a pair of Ziploc® bags couldn’t fix. I’ve used the iPad in temperatures so low that only a few minutes of touch-display would work before the iPad had to be warmed up again before responding to a fingertip. Battery life was not a problem, but it was definitely less than under optimum conditions according to the battery-life indicators.

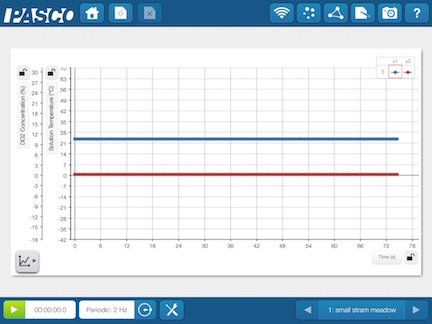

The data from the pond shows changes in both DO and Temp during the probes decent. The probe was paused for about five seconds every half-meter. The inverse relationship between DO and Temp is clearly presented in the graph, and occurred at approximately the middle depth of the pond which from summer measurements is slightly less than 3m deep. A joy in data such as this is found in the inspection of either DO or Temp across depth in isolation, and in relation to each other across depth.

A bridge above a small stream provided an excellent basecamp to collect DO measurements in the center of the flow. The 3m cable length was just enough to reach the water. The beefy UZBL case provided plenty of grip even while wearing gloves to make working ten feet above the water of less concern then slipping around in my own boots.

The power of a Bluetooth-connected Dissolved Oxygen probe is not only from the DO data, but the places the data can be collected, and the ways the data is presented. Over the holidays I took the Pasco wireless DO probe up in the mountains to generate some data and answer some questions.

Science "home"work for interested students

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2015-01-07

I have several students this year who are really into science. I’d like to provide or suggest some elementary-level projects or activities that parents can do with them at home to encourage this interest. Do you have any ideas beyond book lists and activity sheets? —M. from Maryland

I have several students this year who are really into science. I’d like to provide or suggest some elementary-level projects or activities that parents can do with them at home to encourage this interest. Do you have any ideas beyond book lists and activity sheets? —M. from Maryland

Your desire to foster student interest in science through science activities with their families is commendable. Creating formal projects for this group of students would require time on your part to organize and could be a burden for families in terms of time and resources. But there are many ways to involve students and parents with informal and enjoyable science-related activities.

In your school or class newsletter, website, or blog, include information about free events at local parks, nature centers, libraries, or museums. Encourage students who attend these events to share their experiences and photographs. NSTA’s SciLinks can help you create a list of appropriate websites related to your unit topics that you could share with parents.

Annotate the school or class calendar with prompts for family conversations (What is your first memory of being outdoors? How have inventions and technology changed over the years? Play I Spy at home and find objects made of metal, plastic, glass, wood. Talk about where food comes from.) If you involve other subject areas, every day on the calendar can have a conversation-starter. Encourage children and their parents/caregivers to build with blocks, walk and play outside if possible, grow a garden or even a few house plants, observe a pet’s behavior, or cook together (reinforcing measurement, nutrition). If your students and their parents speak another language at home, it would be helpful to have several versions of your suggestions.

I worked with an elementary school that had take-home “kits” in plastic bags, created by volunteers from a high school service group (backpacks or pizza boxes could also be used to organize the kits). The student- and parent-friendly materials were donated or bought at a dollar store or flea market. For science, these kits included CDs or DVDs with podcasts of science programs, trade books to read at home with suggested discussion questions, small collections (such as leaves, seashells, rocks, or pictures) with directions on sorting or identifying, a plastic ruler and a magnifying glass with some simple directions for observing and collecting data, maps of the night sky for star gazing, an inexpensive pair of binoculars and a field guide on birds, and sets of building blocks. Students signed out a kit to take home, and they were not “graded” on the use of the kits. Of course, some kits never made it back to the classroom, but that didn’t discourage the teachers from continuing the project. A project such as this would require your time or a group of volunteers to create, sign out, inventory, and replenish the kits.

Students could make small journals to take home with suggestions on each page for something to observe, illustrate, and write about (e.g., the weather, phases of the moon, insects, clouds). If you have a class website, students and parents could send photographs or writing to include (you would want to monitor and moderate this process, however, and provide guidelines and examples).

You could suggest citizen-science or collaborative research in which students, parents, and teachers participate in existing projects with science institutions and organizations. SciStarter is a searchable collection of these projects–regional, national, and international. There are projects appropriate for all grade levels and on a variety of topics. It’s a win-win scenario for all involved—the sponsor gets additional observers and data-collectors, parents and their children can work together on them, and the students get experiences that can extend into careers or lifelong learning. Follow SciStarter on Faceboook or Twitter for the latest projects.

Some parents may feel that they don’t have enough background in science, but how you introduce and promote the activities can encourage them to learn with their children. You’re giving “home” work a whole new life!

Additional resources and suggestions from NSTA:

- This Earth Day, Engage Kids in Citizen Science!

- Citizen science: Collaborative projects for teachers and their class

- Community-based science

- Citizen Science: Engaging Students Through Public Collaboration in Scientific Research

- Citizen Science (December 2012, The Science Teacher)

- Community-Based Science (March 2010, Science Scope)

- Getting Families Involved (February 2012, Science & Children)

- Informal science is one of NSTA’s online discussion forums

- Peggy Ashbrook, author of the monthly Early Years Column in Science and Children and the Early Years blog has been an advocate of citizen science for our youngest scientists.

Photo: http://www.flickr.com/photos/glaciernps/4427417055/in/photostream/