Classification

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2009-03-09

Snack sorting! It’s an interesting way to involve students in classifying and, while sitting together to eat, there is time to talk about why certain groupings were chosen. Children might sort by shape, create an ABAB pattern, and count the number of each snack shape.

Snack sorting! It’s an interesting way to involve students in classifying and, while sitting together to eat, there is time to talk about why certain groupings were chosen. Children might sort by shape, create an ABAB pattern, and count the number of each snack shape.

Classification is the theme for the March 2009 issue of Science and Children

Classification is the theme for the March 2009 issue of Science and Children

I was especially interested in the performance standard scale for the process of classification developed by a group of first-grade teachers in the Coast Metro school districts of British Columbia, Canada (see “Classifying Classification”, pgs. 25-29). The scale details the skills and behavior that may be seen in first graders as they classify and answer these questions:

I was especially interested in the performance standard scale for the process of classification developed by a group of first-grade teachers in the Coast Metro school districts of British Columbia, Canada (see “Classifying Classification”, pgs. 25-29). The scale details the skills and behavior that may be seen in first graders as they classify and answer these questions:

How are these the same? How are they different? Is there another way you can sort theses into groups? Where would you place this new item in your system? Explain.

The teachers put classification skills on a continuum from Matching, to Sorting, to Categorizing, to Interpreting, “to help them describe how students move through different levels of classification tasks.”

I’m eager to apply this model to the next classification task I introduce in my teaching, and improve the sequence of classifying tasks we work on next year.

Peggy

Activities get students focused

By MsMentorAdmin

Posted on 2009-03-08

Nick, Paterson, New Jersey

Even good classroom management can break down at times students are transitioning: from one class to another, between activities, or at the end of a class. “Bell-ringer” activities take advantage of these times. They are not unrelated busywork. They are brief—usually written—activities that encourage students to focus their attention or reflect on the lesson.

At the beginning of the class, have the bell-ringer (or warm-up) ready when the students come in. They should get started right away, even before the bell actually rings. The students are engaged while you take attendance, distribute or return assignments, or check homework. Some examples of warm-ups include:

- Answer a question about yesterday’s work or another related topic;

- Respond to a statement or visual to uncover any misconceptions or to activate prior knowledge of the topic;

- Solve a quick brain-teaser or math problem;

- Complete a vocabulary entry with a graphic organizer such as a Frayer diagram;

- Do a “quick write” with several sentences on a theme or topic;

- Do a “quick draw” on a theme or topic;

- Put a few words on the board and ask the students to write a sentence using all of them; and

- Respond to a “this date in science history” or current event

At the end of the class, use another bell-ringer (sometimes called an exit activity or a ticket-out-the-door) as a formative assessment to check student understanding through a summary or a brief response to a question. This also gives time to scan the room to make sure materials are put away. Beyond classroom management, exit activities get students to focus and reflect, instead of dashing from the end of one class to another without “packing up” their thinking. But be sure that the exit activity doesn’t make students late for their next class. I know a teacher who has an official “time keeper” in the class to give him a five-minute warning!

Bell-ringers have many formats. Some teachers use a notebook page. Others use a single sheet of paper divided into sections for each day or small pieces of paper (recycling old handouts) that can be turned in. If students have laptops, they can add to a class blog or Wiki. Do students respond positively? They may not at first, but don’t give up! It may take time for this to become a routine.

Some teachers grade bell-ringers; others include them in a class participation rubric. Some collect them and then return them at the end of the unit to review. But be sure to skim them to identify what students do or do not understand. Refer to their work the next day: I noticed that yesterday some of you had questions about… It seems like you understand… I saw an interesting connection between… I observed a teacher who asked the students to put a “Q” in the top right corner if they wrote a question or a check mark if they wrote about what they learned. He skimmed through the papers and used the questions and understandings to guide the next lesson.

You asked, “Do they really work?” I haven’t seen any formal published research on bell-ringers per se (a possible thesis idea for graduate students?). But research (described in Robert Marzano’s Classroom Instruction That Works ) shows positive effects for strategies often used in bell-ringers (e.g., activating prior knowledge, the use of nonlinguistic representations, and summarizing). I’ve seen them used in all kinds of schools, grade levels, and subject areas. My own action research sold me on the topic, and I wouldn’t teach a class or conduct a workshop without bell-ringers.

If anyone has examples of bell-ringers activities you’d like to share, please add a comment.

Seed sprouting, activity and observation

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2009-03-07

It’s fun for children to plant seeds in a special container, but it can be hard to remember to water them, leading to disappointment if the plants don’t survive. Planting grass seed in some bare spots on any lawn is just as satisfying, perhaps more so because with time it will be hard to say which grass plant is the “one” they planted, and therefore they can claim the success of all. Seeds which are often successful in the classroom include:

- Mung bean seeds. These small green beans grow into the bean sprouts in Asian foods. They sprout quickly in water or in soil.

- Grass seeds.

- Mixed bird seed. Many brands contain peanuts—are there any children in your class with an allergy to peanuts?

Note of Caution! Avoid using kidney beans or fava beans. Kidney beans, when raw or slightly cooked, have a high concentration of the naturally occurring toxin, phytohaemagglutinin. In people who have inherited a deficiency of a certain blood enzyme, eating fava beans can cause favism, a type of severe anemia. Children with this deficiency may be especially affected. See the US Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Food Safety site and the Cornell University, Department of Animal Science for additional details.

Here are some ideas about where children can sprout seeds,

- Outside in a garden.

- Indoors inside a plastic bag.

- Indoors in a clear container of soil polymers (sometimes called “water crystals”), a polymer that absorbs water and has a clear, jelly-like consistency so root growth can be easily seen.

- Grass seeds are often grown as “hair” on a “head” made of a small cup of dirt with a face drawn on it. Other materials for the head include a nylon stocking foot with the seeds and dirt tied into a ball inside, and empty food containers with stickers forming the face.

After children have had some experience sprouting seeds, a simple experiment can be set up to see if varying the amount of water (which also controls the amount of air) affects sprout growth. Children may be able to design and set up the experiment, depending on their age and experience with seed sprouting and plant growth.

After children have had some experience sprouting seeds, a simple experiment can be set up to see if varying the amount of water (which also controls the amount of air) affects sprout growth. Children may be able to design and set up the experiment, depending on their age and experience with seed sprouting and plant growth.

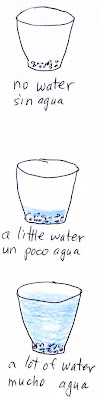

- Label three clear cups (see the photo below) to indicate the amount of water to be maintained in each cup. (Most three-year-olds recognize the blue color in the labels as water, and we discuss how the color is a symbol for water—the water we’re using is really clear.)

- Add the water and draw a line around the cup indicating the level to be maintained.

- Each scientist adds mung bean seeds to the cup that they feel is the best environment for successful sprouting. Some children put seeds into certain cups because their friend did, or because no one else did, not because they are thinking about what will happen. (It’s a fine line between talking about experimental design so much that the excitement disappears while waiting for action, and trying to make sure the children’s choices are motivated by some thinking about the needs of seeds.) Then additional seeds are added (by an uninterested party!) to make the number of seeds equal in each cup.

- Have the children draw the 3 cups and contents.

- Tell the children that the cups are the same, the number of seeds is the same, and the location of the cups is the same, and ask them what is different? Most of the children will be able to identify the different amounts of water but few (if any) will comment on the seeds’ access to air.

- The seeds will sprout within a week and by the second week it will be evident which cup provides the needed environment. Maintain the marked water levels by adding a little if necessary.

(Spoiler alert: stop reading here if you don’t want to know the results of this experiment before you try it yourself.)

No change will have occurred in the cup with no water, the cup with a lot of water will have sprouted and rotting beans, the cup with a little water will have bean sprouts with bright green leaves above the water and roots in the water. Discussion of personal experiences with “too much water” and drawing the results may make the children aware of how access to air is important for plant growth.

What development towards understanding concepts such as, what is alive, needs of seeds and plants, and what is air, have you seen in your class?

Peggy

It’s fun for children to plant seeds in a special container, but it can be hard to remember to water them, leading to disappointment if the plants don’t survive. Planting grass seed in some bare spots on any lawn is just as satisfying, perhaps more so because with time it will be hard to say which grass plant is the “one” they planted, and therefore they can claim the success of all. Seeds which are often successful in the classroom include:

An admin's eye view of teaching lab activities

By AnnC

Posted on 2009-03-06

I think administrators are evil. Or maybe it’s more accurate (but much less inflammatory) to state that they’re dangerously misinformed. One of the reasons I feel this way is because of the teaching load (and therefore value) ascribed to laboratory teaching.

At my school, those of us in the sciences are given credit for half of the time we spend in lab with our students as a part of class. In other words, for every two-hour session I get credit for one hour of teaching. I’ve talked with other instructors at other schools, and my general impression is that this is about low average. In other words, most of us are being told that our time in the lab is worth about half the time we spend in ‘lecture’. That’s the value the students get out of it, and that’s about the amount of time we need to spend thinking about it.

The rational extrapolation of this is that our research as scientists is also worth about half. It must be because it also takes place in a laboratory and (if we’re doing our jobs right), looks much like our lab assignments for our students.

Gee! Talk about needing more hours in a day? If I’m researching or teaching in a lab setting, I need 48 just to come up even with instructors across campus who do not teach with a laboratory or practicum experience. No wonder it seems I get nothing done!

So I’m truly puzzled when my days of lab leave me far more exhausted than my days of lecture sessions. How come I’m so tired if I’m only working half as hard?

And what about moving toward active learning in my classroom? Well, for reasons of both practicality and safety, any chemistry student should be in the lab if they’re doing active learning, so…oh no!!! My administrators can’t tell the difference!! Wait!! There ISN’T a difference!! A good lab IS active learning already.

The only rational conclusion is that I’m working like crazy, and so are my students, but somehow the value is only half that of those same students sitting quietly (probably texting one another) in a history lecture in another building not a tenth of a mile away. Wow. How humbling!

On my worst days, I think it might be better for my students if I just pack it up and go back to industry where—for some unknown reason—they paid me for a full day’s work.

In the lab.

I think administrators are evil. Or maybe it’s more accurate (but much less inflammatory) to state that they’re dangerously misinformed. One of the reasons I feel this way is because of the teaching load (and therefore value) ascribed to laboratory teaching.

Challenges and Solutions for ELLs

Classifying Classification

Science across disciplines

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2009-02-28

In a presentation I attended last year, Dr. Rita Colwell, the former director of the National Science Foundation, described 21st century science as “international and interdisciplinary.” Interdisciplinary is one of those words that is hard to define, but we “know it when we see it.” The article Thinking, Teaching, and Learning Science Outside the Boxes does provide a definition as well as a discussion of its importance and even a “taxonomy” of levels of disciplinarity (yes, I know that’s not a real word!), showing that it’s not an either/or dichotomy. It would be interesting to compare our unit plans with this taxonomy.

In a presentation I attended last year, Dr. Rita Colwell, the former director of the National Science Foundation, described 21st century science as “international and interdisciplinary.” Interdisciplinary is one of those words that is hard to define, but we “know it when we see it.” The article Thinking, Teaching, and Learning Science Outside the Boxes does provide a definition as well as a discussion of its importance and even a “taxonomy” of levels of disciplinarity (yes, I know that’s not a real word!), showing that it’s not an either/or dichotomy. It would be interesting to compare our unit plans with this taxonomy.

Other articles in this issue illustrate activities at these levels: studying biofuels and nanotechnology, building rubber-band cars, integrating science and the arts, and collecting and analyzing hydrology data. These are very powerful kinds of investigations, not simply contrived or superficial collections of activities. Scan your back issues of NSTA publications for more excellent examples. If you need some web resources to get similar units started, check out the Scilinks categories Alternate Energy Sources, Nanotechnology, and Leonardo da Vinci.

I’m sure that most of us have tried some level of interdisciplinary studies. But there are some real challenges (especially at the secondary level). Trying to find common planning time with other teachers is difficult. (Wouldn’t it be a great use of professional development days to actually research a topic and plan some units as an interdisciplinary team?) The students in a science class might report to 2-3 different teachers in math or other subjects. But my favorite is teachers who say “We already so this.” I know that this is certainly true in many cases, but I wonder if having students draw a picture, calculate an average, or write a report represents the highest levels of true interdisciplinary instruction (I’ll have to check the taxonomy.)

I had the opportunity last week to visit several high schools. Although it was for a different project, I kept my eyes open for ideas for interdisciplinary activities. For example, I saw an opportunity for connecting an American history unit on 19th century industrialization and inventions with science units on electricity, machines, and energy. In another class, a student asked “So how does all of this fit together?” I suspect that when we do interdisciplinary studies, we as teachers see the connections and we assume that the students will, too. But we need to show the students how things are connected and model how to make the connections.

It also occurred to me that elective courses are where many students start to see the connections and applications — robotics, graphic arts, technical writing, computer applications, marketing/advertising, culinary arts, etc. And yet often these courses do not “count” much for the GPA or honor roll and are the first to go when there are budget cuts. Hmmm.

Having read this issue, I realize now that when my colleagues and I did our “interdisciplinary” field trip every spring, what we really had was a collection of parallel activities. What we needed to do was identify a theme, a problem, or an essential question to connect the activities. We could still do the same activities, but the theme or question would would focus the students’ attention better and help them see the connections.

Please feel free to share any themes or questions that you have used to plan interdisciplinary learning.

In a presentation I attended last year, Dr.

In a presentation I attended last year, Dr.

Designing a laboratory

By MsMentorAdmin

Posted on 2009-02-25

We are opening a new academy for grades 10, 11, and 12. We’re going to have a science lab for combined use in biology, chemistry, and physics. I’ve taught in labs, but I’ve never designed one. Where do we start?

—K. D., Oklahoma

There’s nothing more exciting for a science teacher than walking into a new laboratory. The first thing we notice is the equipment. But there’s a lot more to designing a lab than selecting and installing the tables.

Whether you’re constructing a new facility or remodeling an existing one, planning the lab facilities is a complicated process. It’s better to work out all the details in advance than have to go back and correct any mistakes or omissions. I would strongly recommend that you start with the NSTA Guide to Planning School Science Facilities, available through the NSTA Science Store. This publication has a chapter on safety guidelines (including storage of materials), sample floor plans, Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) guidelines, and even suggestions for “green” labs. It has user-friendly chapters on the steps of this planning process, lots of photographs, and checklists. It also is essential you research recommendations or requirements from your state department of education and your local building codes.

I assume you are going to meet with all of the science teachers for their input. Ask a lot of questions: What kind of science instruction would take place in the lab: lecture/discussion with supporting lab activities vs. an inquiry-based curriculum with ongoing activities? How many students will be in a class? What kinds of investigative processes are suggested or required in your state’s science standards? What will be the role of technology? The NSTA Guide has many discussion-starters.

The first priority should be safety: features such as showers, eyewash stations, fume hoods, air exchangers, fire extinguishers and blankets, sanitizing equipment for goggles, master shut-off switches (for gas, water, electric), adequate and uncluttered workspace dimensions, room size, and unobstructed exits from the lab. The NSTA Guide explores what should be in place so that students and teachers can work safely. The Council of State Science Supervisors also has recommendations in their publication, Science Safety: Making the Connection.

I talked to several other science teachers who suggested:

If anyone has other suggestions for K.D., please feel free to add a comment!

We are opening a new academy for grades 10, 11, and 12. We’re going to have a science lab for combined use in biology, chemistry, and physics. I’ve taught in labs, but I’ve never designed one. Where do we start?

—K. D., Oklahoma

There’s nothing more exciting for a science teacher than walking into a new laboratory. The first thing we notice is the equipment. But there’s a lot more to designing a lab than selecting and installing the tables.

Classification

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2009-02-23

In last month’s issue of Science and Children, Bill Robertson asks the question “Why do we classify things in science?” He notes that many teachers teach classification as an end in itself or as a communications exercise. He suggests that “Classification in the classroom should lead toward the understanding of concepts, or at least should be done with an eye toward the ultimate purpose, such as the classification of rocks leading toward an understanding of the formation of geologic features” (page 70).

In last month’s issue of Science and Children, Bill Robertson asks the question “Why do we classify things in science?” He notes that many teachers teach classification as an end in itself or as a communications exercise. He suggests that “Classification in the classroom should lead toward the understanding of concepts, or at least should be done with an eye toward the ultimate purpose, such as the classification of rocks leading toward an understanding of the formation of geologic features” (page 70).

I visited an elementary class in which the teacher had a collection of small objects, which the students were to categorize. The students had lively discussions as they sorted the objects into the compartments of a cafeteria tray. But the teacher went beyond this simple activity – she had the teams exchange trays and try to figure out what characteristics the other team used to create the groups. Then she gave them some new objects and asked where (and if) the objects fit and whether the groups should be changed or expanded to accommodate the new objects. Two of the articles in this Science Scope also take classification one step further, with follow-ups to scavenger hunts using GPS units and digital cameras!

There are many terrific websites that help students understand the concepts of biological classification, such as those in the Explore Classification section of SciLinks. But let’s not forget that other sciences also use classifications such as the the Periodic Table, simple machines, galaxies, and hurricanes.

Regardless of the subject, instructing students in the process of identifying similarities and differences (through the processes of comparing and classifying) has been found to improve student achievement. In Classroom Instruction That Works. Robert Marzano and his colleagues cite this research and describe two types of classification activities: 1) giving students the categories and asking them to classify items and 2) giving students the items and asking them to sort them into categories of their own creation. The authors note that using graphic organizers can help students to determine the patterns. And science is full of graphic representations of classifications schemes (just think of what can be learned from looking at the Periodic Table). History of Life: Looking at the Pattern depicts the current thinking about how living things are classified based on patterns and observations.

How many of us learned that Pluto was classified as a planet and that there are three kingdoms of living things? It’s exciting to see how new information causes us to rethink what we thought we knew.

In last month’s issue of Science and Children, Bill Robertson asks the question “Why do we classify things in science?” He notes that many teachers teach classification as an end in itself or as a communications exercise.

In last month’s issue of Science and Children, Bill Robertson asks the question “Why do we classify things in science?” He notes that many teachers teach classification as an end in itself or as a communications exercise.