People have been making since the first human used a tool, and have continued to create things for both fun and function. From building model trains to quilting, from woodworking to baking, people have for centuries been enriching their own lives by following their passions and enriching others’ lives by sharing their knowledge and the products of their labor. The recent “Maker Movement” celebrates the value of these hands-on activities, and the education community has recognized that making is a meaningful way for young people to engage in the same process that science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) professionals use to design solutions to real-world problems (Blikstein and Krannich 2013; Vossoughi and Bevan 2014). Maker programs often use a Project-Based Learning (PBL) approach focused on process rather than product, supporting problem-solving and critical thinking. The Maker programs, however, are distinct from PBL in their particular emphasis on having participants use tools (sometimes digital), build objects, and engage in the engineering design process (EDP) (Chan and Blikstein 2018). Over the last 10 years, makerspaces have been opening up in science centers, museums, libraries, and schools, attracting people from all age groups and offering opportunities to brainstorm, plan, prototype, test, revise, and finalize creations that reflect makers’ personal interests (Honey and Kanter 2013).

The interest-driven nature of maker programming inspired the IDEAS project. People on the autism spectrum are as heterogeneous as any group of people, but one trait that many have in common is that they develop deep, focused interests in particular topics. In formal educational settings, these interests are sometimes pathologized and treated as something they need to overcome so that they can focus on their school work or learn how to socialize around mainstream topics. However, research has shown that interventions that draw on these focused interests actually help students with autism improve their social, academic, and executive function skills (Gunn and Delafield-Butt 2015; Kaboski et al. 2014; Koegel et al. 2012; Kryzak and Jones 2015). People in the general population socialize around their interests and are more compelled to complete tasks that interest them than tasks that do not, so these findings make sense (Ito et al. 2013). Providing youth on the spectrum with opportunities to pursue their interests alongside peers can help them realize that the things they care about can connect them to others and the wider world, rather than separate them. This is true of students with a range of challenges and abilities. Making is particularly relevant for youth who are interested in STEM, as well as art and design, because it requires them to go through the creative and iterative processes that are naturally part of those fields (Bevan, Ryoo, and Shea 2017). With continued poor postsecondary and career outcomes for youth with autism and other disabilities, it is essential to develop programs that will enable this segment of the population to gain the social and executive function skills needed to engage in meaningful work, and to ensure that society can discover the unique perspectives these individuals can offer (Anderson et al. 2014; Shattuck et al. 2012; Wei et al. 2013; Wei et al. 2018).

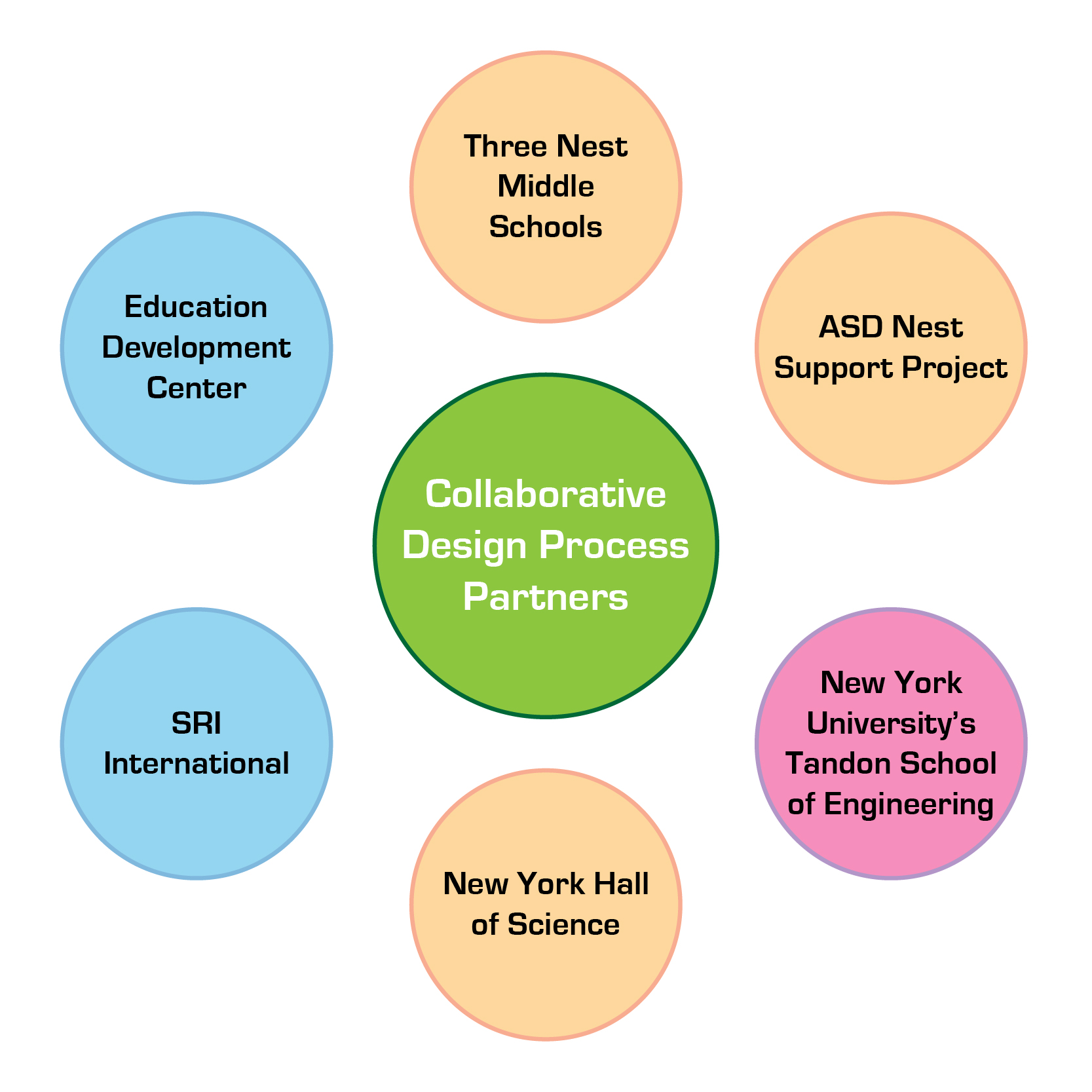

Collaborative design process

The team used a collaborative design process to adapt a museum-based 3-D Design and Fabrication Maker Program for autism inclusion middle schools. This process required the involvement of various stakeholder groups, but especially those who would be using the program, since the program must meet their needs and fit within their normal practice to be implemented sustainably.

One stakeholder group consists of experts from the Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) Nest Support Project at New York University (NYU)’s Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development. This group provides training and support for educators working with students with ASD, including those in the New York City Department of Education’s ASD Nest Program (Nest). Currently, Nest is in 48 elementary, middle, and high schools across New York City. The program includes more than 1,400 students on the autism spectrum, all of whom are verbal and academically at grade level, learning alongside 4,500 general education peers in classrooms that are cotaught by one general education teacher and one special education teacher. The Nest model uses a strength-based approach to support students on the spectrum. This approach focuses on identifying students’ strengths and interests and building on these to promote social and functional skills, rather than remediating students’ weaknesses. For example, if a student is deeply interested in dinosaurs and talks about them often, a remedial ASD intervention might offer the student a reward for talking about something other than dinosaurs. By contrast, a strengths-based approach would have teachers use dinosaurs as a conversation topic to get the student to engage with peers or as an essay topic to inspire the student to plan, research, and complete a piece of writing. ASD Nest Support Project staff believed that a maker program would closely align with the strengths-based approach that they already used, because making encourages students to pursue their interests.

Another important partner in this effort was the New York Hall of Science (NYSCI). NYSCI is a leader in maker programming, hosting a Maker Faire each year that is attended by tens of thousands of visitors and maintaining a makerspace where they offer summer and afterschool programs, as well as drop-in workshops and field trip experiences. NYSCI also provides teacher professional development (PD) in maker education. NYSCI’s 3-D Design and Fabrication Summer Camp Program was the springboard for the IDEAS project.

Three Nest middle schools were key partners, serving as pilot sites for the program. Two to four teachers (special education and science) per school were vital members of the design team. They took part in the initial discussions in which NYSCI’s 3-D Design and Fabrication Summer Camp model was adapted for use within middle schools. They also pilot tested the activities and provided feedback on the curriculum drafts throughout the three-year process.

NYU’s Tandon School of Engineering was another partner. Two graduate engineering students were part of the design team for the first two years of the program, helping to facilitate the maker activities in the schools and design the curriculum materials.

Education Development Center (EDC) was the research partner, organizing and documenting the design and implementation process and working closely with SRI International to collect and analyze additional quantitative data.

The first step in the collaborative design process was to have the director of the ASD Nest Support Project and an EDC researcher meet with the principals at each of the three participating Nest middle schools. We gave the principals an overview of the project goals and research plan, but we spent most of the time listening to what the principals wanted, how they imagined making could benefit their students, and how it could fit within their school’s culture and normal practices. For example, one school had existing lunchtime clubs, so we decided to conduct the program as a lunch club twice a week. The other two schools already had afterschool programs, so it made sense to offer the Maker Club after school once a week.

Year 1

In the first year of the project, before beginning the design process, team members participated in cross-trainings to ensure that all understood making and autism support techniques. Subsequently, design team members met biweekly to go through each of the activities in the NYSCI 3-D Design and Fabrication Maker Program. During these meetings, team members brainstormed ways to break up the activities into smaller and more manageable chunks, provided additional information for educators new to making, and identified autism supports that might be useful, such as checklists and visual templates.

In the spring of the first year, we pilot tested the draft program. A maker educator from NYSCI facilitated the activities, with help from the teachers on the design team and graduate students. EDC researchers observed all of the sessions and later interviewed teachers and students about their experiences. Over the summer, we further adapted the curriculum to enable teachers with no maker program experience to facilitate the activities as well.

Year 2

In the second year, the teachers on the design team piloted the lessons with help from the graduate students. At the middle and end of the year, we debriefed the teachers on their experiences and gathered feedback to inform the next iteration of the curriculum.

Year 3

In the third year of the program, the teachers on the design team implemented the revised program on their own. Midway through the year, we conducted a final debriefing session to gather feedback for the final revision of the curriculum. We also discussed possible ideas for sustaining the program after the grant ended, integrating making into science instruction more broadly, and further adapting the program for elementary, high school, or self-contained special education populations.

The IDEAS Maker Program

The IDEAS Maker Program curriculum is housed on the ASD Nest Support Project website. The curriculum has been designed as a set of 12 activities that build on one another:

1. One Sheet of Paper: Students make a 3-D object out of a sheet of paper and discuss the properties of 3-D objects.

2. Journal Making: Students create a design journal using various materials (e.g., cardstock, string, decorations) and tools (e.g., hammer, nails, sewing needles). This activity introduces students to the need to document their ideas and plans.

3. Intro to 3-D Printing: Students use different materials, such as their bodies, Play-Doh, glue guns, and foam core, to understand how a 3-D printer works and its limitations. This activity also introduces students to the EDP.

4. Wooden Blocks: Students create a 3-D version of their initials or names using wooden blocks and learn how to position them for optimal 3-D printing.

5. TinkerCAD: Students learn the basics of CAD design software and digital 3-D design by transferring the design of the wooden block initials to TinkerCAD.

6. Paper Circuits: Students create a paper circuit to light up an LED and learn about the flow of electricity and how LEDs work.

7. LED Greeting Cards: Students design a card for a special occasion that uses LEDs.

8. Motors: Students design a vibrating robot or other moving object using motors and other craft materials.

9. Final Project Sketching: Students brainstorm and sketch ideas for a final 3-D design project that uses the skills they have developed.

10. Prototype Take One: Students create initial prototypes to test ideas for their final project.

11. Prototype Take Two: Students expand on their first prototype to improve it and develop a final project.

12. Final Project Board: Students create a poster that presents the maker’s journey from the initial sheet of paper to the final 3-D printed object.

We conclude the program with a showcase, in which students present posters and the various projects they made in the club. These showcases take place at their individual schools, with peers, teachers, administrators, and parents attending, and also at NYSCI, where they show their work to the makers and teachers from other schools as well as the general public. At the end each student is presented with a certificate of completion.

The curriculum comes with detailed instructions for teachers on facilitating the activities (Figure 11), as well as the following:

- A materials list for the specific activity

- Information about how to prepare for each lesson, including suggested language to use

- Guides and links to videos showing how to facilitate the final project brainstorming discussions

- Checklists for supporting executive function

- A master materials list to use when ordering materials before the program starts

There are also additional visuals to support all students, but particularly students on the autism spectrum. For example, although anyone who participates in maker programming will likely engage repeatedly in the EDP, the curriculum includes a visual model of the EDP for teachers to put up as a poster and for students to include in their design notebooks. The latter enables students to refer to the EDP throughout the program, to help them see where they are in the process, and to make it clear that obstacles such as prototype failures are not a problem but an integral part of the design process (Figure 12).

While the program has a detailed curriculum, teachers were able to use its materials flexibly, taking components they needed, improvising, and even creating additional materials such as PowerPoint slides listing each activity’s objectives. This flexibility meant that some students chose to participate in the club more than once over the years. Even though the sequence of activities was the same, students could make unique objects each time, so they remained engaged with the process.

Table 1

Different implementation formats for the IDEAS Maker Program

Table 2

IDEAS Maker Program participation over three years

In this final year, the IDEAS Maker Program was implemented at the three participating schools in three different ways (see Table 1). Teachers had no difficulty recruiting for the clubs. About 25% to 50% of the students in each club were on the autism spectrum (see Table 2). All of the teachers from the design team were able to run the program without any assistance from researchers, museum staff, or graduate students. In addition, they were able to order most of the materials through their district purchasing system.

Data collection and initial findings

Throughout the project, the research team has collected the following data about the program, on which we will report in this article[1]:

- Observations of the program sessions

- Interviews with teachers, principals, students, and parents

- Audio and video recordings of five students’ (four on the spectrum) social interactions over two weeks for a pilot study

Our findings from the observations and interviews indicate that interest-driven maker programming is well-suited to supporting the way youth on the autism spectrum think, work, and interact. All of the students on the spectrum successfully completed program activities and final projects and presented their projects at the maker showcases. Teachers running the program reported that they needed fewer ASD supports in their Maker Clubs than they typically needed during the school day, and that students were able to work through frustration, initiate and complete projects based on their interests, and socialize with peers far more than they did during the school day. Of particular note are some individual cases:

- Robert[2] was very interested in science and spent science class constantly asking questions related to his own interests rather than the topic being taught. Teachers reported that once he joined the Maker Club, he was able to “save up” his off-topic questions, discuss them with the science teacher who co-led the club, and delve deeply into his interest in electronics. Robert created his own laptop computer as his final project.

- Eduardo was socially disengaged and would pace and talk to himself about his personal interest in geopolitics during class and lunchtime. In the Maker Club, he designed a project based on this interest—a board game on the colonization of Africa. He also discovered that another student in the Maker Club shared his interest, and they developed a friendship that extended outside of the club. His pacing and self-talk during the school day decreased.

- Cooper was socially disengaged from his peers and would spend a lot of time scripting, or repeating things to himself, instead of engaging in conversation with others. In class, he would only do the bare minimum of work to get by. In the Maker Club, however, he was extremely productive, quickly coming up with project ideas that reflected his interests in food and internet memes and designing objects such as a cupcake maker and a meme bingo game. He would talk to his peers about the things he made with a sense of humor that his teachers and peers had not seen before.

We also conducted a pilot social engagement study that analyzed video of five students over two weeks of the program. We analyzed the video using existing ASD research protocols (Bauminger 2002; Usher et al. 2015). The analysis of the pilot data showed that three out of the five observed Nest students engaged in social interactions for over 50% of the observed time, a higher rate than the general education students. This interaction was characterized by increased frequency of spontaneous social initiation, attentive responses to others, and reciprocal conversations with peers (Koenig, Martin, Vidiksis, and Chen 2018). Teachers elaborated on these findings in interviews. For example, one teacher expressed the following about a boy in the club:

"He started off as someone who was completely isolated, struggling. When we first met him he would cry often. He would be in the hallway at least three times a day. School was overwhelming; it triggered so many things. And then he joined the club and he found friendship… He found other people that have the same targeted interests as him.”

When a teacher from another school was asked if she had observed any program-related benefits carrying over into the regular school day, she said:

"I think the social component of it. I supervise lunch duty and I see them sitting together and I see [non-Nest] students now interacting with the [Nest] students, who they wouldn’t interact with [before]…Part of the reason why they’re interacting with each other is because they have something in common to talk about.”

A teacher described a particular interaction a student made during the Maker Club:

"He initiated a meaningful interaction with two girls who he doesn’t talk to on a regular basis. That was one example where I saw that he was able to move past himself, be able to read the room, find something that he liked, and then initiate an interaction. I thought that was something that I really was able to see that was different from before.”

Lessons learned

The process of codesigning and iteratively testing a maker program in autism-inclusion middle schools has helped us learn a number of important lessons about program development that can be applied to similar efforts:

- Build a shared understanding across partners. The project team started with a general goal of bringing maker programming to autism inclusion schools in New York City. However, because the partners came from different disciplines (autism support, education, informal STEM programming, research, and engineering), we had to make a concerted effort to understand what that meant from each other’s perspectives. Having all of the project team members trained in autism support techniques and maker education helped us build knowledge and empathy. In addition, having multiple stakeholders participate in the design meetings was essential for ensuring that the program design choices made sense to all of the participants.

- The program should address the needs and contexts of schools. It would be futile to develop a program that would not work within the norms and constraints of the schools for which it was created. Rather than diving into the program design and then later trying to convince schools to use it, we started with the notion that administrators and teachers at the participating schools had to set the parameters within which the design team had to work. We conducted the iterative testing in the settings in which the program would take place so we could immediately understand the challenges and opportunities within those environments.

- Knowledgeable, school-based facilitators should run the program. One key element of this program is that it was intended to be run by teachers, particularly special education teachers, from the schools in which it takes place, and not by outside informal educators. This is crucial for a number of reasons. First, all of the teachers in these inclusion schools have training in autism support techniques and are experienced working with this population. Second, many of the teachers knew the specific students in the program and therefore understood what particular techniques worked for them. Third, because of the need to organize and store materials and student work, having teachers who were familiar with the building and who had easy access to classrooms and storage spaces was valuable.

- Making can help educators know their students better. Because making allows participants to pursue interests in the depth and the ways that they want, students on the autism spectrum needed fewer supports in the program than they normally needed in class. Facilitating the maker program gave teachers an opportunity to see what their students on and off the spectrum were capable of accomplishing without the pressure of covering subject area content. Some students were able to engage productively and interact with peers in ways that the teachers had never seen before. That changed the teachers’ expectations of their students.

- Making lends itself to universal design for learning (UDL). Many of the characteristics of maker programming—it is hands-on, visual, kinesthetic, and allows participants to work at their own pace and express themselves in various ways—make it consistent with UDL principles. The instructional supports we developed, such as checklists and visuals, could benefit everyone.

We hope to see the IDEAS Maker Program sustained in the three participating schools, to scale the program to other middle schools, and to create versions for older and younger students, self-contained classrooms, and other districts. We are even considering initiating a new design process in a teacher education program. To learn more about IDEAS, please see our National Science Foundation STEM for All showcase video or listen to podcasts about the program available on the No Such Thing podcast.

Acknowledgment

The program and research described in this article were funded by the National Science Foundation (grant #1614436).

[1] In this final year of the program we are also collecting data that we will report on in a future article:

- Surveys of students’ STEM self-efficacy and career interest based on validated surveys (Bathgate, Shunn, and Correnti 2014; Chen and Usher 2013; Kier et al. 2014) and their understanding of the engineering design process (EDP).

- Assessments of students’ understanding of the EDP based on a validated assessment (Hsu, Cardella, and Purzer 2012)

- Audio and video recordings of 12 students’ social interactions over eight weeks

[2] Names have been changed to protect student privacy.

Wendy Martin (wmartin@edc.org) is research scientist at Education Development Center in New York, New York. Regan Vidiksis (RVidiksis@edc.org) is research associate at Education Development Center in New York, New York. Kristie Patten Koenig (kristie.koenig@nyu.edu) is principal investigator of the ASD Nest Support Project and chair of the Department of Occupational Therapy at the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development at New York University in New York, New York. Yu-Lun Chen (ylc317@nyu.edu) is a PhD student in the Department of Occupational Therapy at the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development at New York University in New York, New York.

citation: Martin, W., R. Vidiksis, K. Patten Koenig, and Y-L Chen. 2021. Making on and off the spectrum. Connected Science Learning 1 (10). https://www.nsta.org/connected-science-learning/connected-science-learning-april-june-2019/making-and-spectrum

I am working on a lesson plan for the life cycle of a plant for kindergarten. Do you have any activity ideas?

I am working on a lesson plan for the life cycle of a plant for kindergarten. Do you have any activity ideas?

Diane Johnson is a Master Teacher for the MSUTeach program at Morehead State University and a Regional Teacher Partner for PIMSER (Partnership Institute for Math and Science Education Reform) at Eastern Kentucky University. Johnson taught high school science for 25 years and served as an instructional supervisor for five years in Lewis County, Kentucky. Additionally, she is a member of Achieve, Inc’s Peer Review Panel and one of NSTA’s Professional Learning Facilitators. Johnson holds a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in biology, and a second master’s in supervision, and is ABD in science education. Follow me at @MDHJohnson and

Diane Johnson is a Master Teacher for the MSUTeach program at Morehead State University and a Regional Teacher Partner for PIMSER (Partnership Institute for Math and Science Education Reform) at Eastern Kentucky University. Johnson taught high school science for 25 years and served as an instructional supervisor for five years in Lewis County, Kentucky. Additionally, she is a member of Achieve, Inc’s Peer Review Panel and one of NSTA’s Professional Learning Facilitators. Johnson holds a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in biology, and a second master’s in supervision, and is ABD in science education. Follow me at @MDHJohnson and  My kindergarten students believe that small objects are always light and big objects are always heavier. How can I address this misconception?

My kindergarten students believe that small objects are always light and big objects are always heavier. How can I address this misconception?