Editorial

Practical Program Evaluation

I love data—especially when used to look at learning experiences and figure out what’s working, what isn’t, and what to do next. Not surprisingly, then, I’m quite excited about this issue of Connected Science Learning, which is all about Practical Program Evaluation. The choice of the word practical in this issue’s theme is intentional. Program evaluation takes time, and time is valuable. Educators have a lot of work to do before thinking about evaluation—so, if they are going to do it, it had better make a difference for their work.

Throughout my career I’ve seen how powerful program evaluation can be when it is done well. For example, a few years back I was project director for a program called STEM Pathways—a collaborative effort between five organizations providing science programming for the same six schools. Much about our program evaluation experience sticks with me: how important it was to involve program staff efficiently and effectively in evaluation design, implementation of findings, and interpretation to decision-making—and how they were empowered by being part of the process; how program evaluation led us to discover things that were surprising and that we would not have otherwise learned; and how the data-informed program improvements we made led to better participant outcomes and program staff satisfaction.

I’ve also seen program evaluation done poorly—such as when it only tells you what you already know, when the information collected isn’t particularly useful for decisions or improvements, or when it fails to empower program staff. We’ve probably all been there at one time or another. But how do we avoid making those same mistakes again?

In my experience, program evaluation that provides utility and value to program developers and implementers by default also satisfies stakeholders. Frankly, if your program evaluation isn’t used for anything more than grant reports, you might want to rethink what you’re doing. Utilization-focused evaluation, an approach developed by evaluation expert Michael Quinn Patton, is based on the principle that evaluation should be useful for its intended users to inform decisions and guide improvement. Patton reminds us to reflect on why we are collecting data and what we intend to use them for—to make sure that conducting the evaluation is worth the time of the people who will implement it, as well as of the program participants who are being evaluated.

The good news is that there is no need to start from scratch. There are many research-based tools and practices to learn from and use, and you will learn about many of them in Connected Science Learning over the next three months. Join us in exploring case studies of program evaluation efforts as well as helpful resources, processes, and implementation tips. You’ll also find articles featuring research-based and readily available tools for measuring participant outcomes and program quality. I hope this issue of Connected Science Learning inspires your organization’s program evaluation practice!

Beth Murphy, PhD (bmurphy@nsta.org) is field editor for Connected Science Learning and an independent STEM education consultant with expertise in fostering collaboration between organizations and schools, providing professional learning experiences for educators, and implementing program evaluation that supports practitioners to do their best work.

Finding Partners for Elementary Science

By Korei Martin

Posted on 2019-07-16

Guest blog post by Wendi Laurence and Laura Cotter

One of my favorite things is discovering new people who can become partners in elementary science programming. While sometimes it is very hard to find those amazing partners; this is a short story about stumbling into one of those partnerships.

A few years ago when I was a STEAM Coordinator at a focus school, I was crawling around on the floor helping students with a Rube Goldberg project. Discovery

Gateway Children’s Museum had an educator onsite working with another age group. Luckily, Laura Cotter the Outreach Education Senior Manager, dropped in.

When she saw the machines the students were building, Laura asked to come in and learn more. It was one of those educators moments when you know you see someone who is all about students learning. She thought it was pretty cool to see the new

STEAM projects taking place and that I was crawling around working with students. I

figured she rocked because she came in and immediately talked to the students –

instead of standing to the side and talking with adults. The conversation after class was one of those where lots of ideas get written down, tons of energy flows and you connect about what might be in science education.

I discovered she was a chemistry major and had worked for years in the pharmacy field. When she decided to take a career swerve, she found the perfect fit at

Discovery Gateway Children’s Museum (DGCM). She was able to merge her love of science, teaching, and an amazing ability to create and manage programming. As we talked, I found out that the DGCM has an amazing professional development program for 5th-grade teachers to learn to teach chemistry. When they have completed the training, they are provided with a curated teaching kit to take back to their classrooms. As a small school just getting rolling with STEAM programming, this was a

great opportunity. From then on, our 5th grade team had great training, materials, and an outreach program that came to school and provided a facilitated chemistry lab experience every year.

A few more conversations into our partnership meant DGCM discovered that I had a

special interest in creating early childhood STEAM learning experiences. Our school became a pilot site, first for their new kindergarten physics curriculum and later piloting components of a professional development program for kindergarten physics.

We partnered to bring museum outreach to different grade levels and connected on field trips, curriculum, children’s literature, and even school gardening. This spring we presented together at the NSTA Elementary Extravaganza in St. Louis.

One of the highlights of our work was being accepted as a team to attend the U.S.

Department of Education’s Teach to Lead program in Nashville, Tennessee. Our team,

a kindergarten teacher, museum educator and STEAM Coordinator, focused on creating a professional learning community centered on supporting early childhood STEAM. A

group of educators is now meeting as a learning community and some members of the team presented together at the Utah Science Teachers Association this winter. The team was just accepted to present at the regional NSTA meeting in Salt Lake City this fall.

Museum/School partnerships can add depth to education programming. Some of our

tips for creating a successful partnership include:

- Value the learning that takes place in both venues and create a bridge between educators in both settings.

- Share resources: references, materials, lessons and share them in places like the NSTA Learning Center where others can access them.

- Learn together: attending conferences together and with other educators has helped increase our network of support for elementary science and museum/school partnerships.

- Get Involved Together: We both support several associations as we are all interested in growing science education opportunities for all students. Create a community: Invite others to join in the fun!

Wendi Laurence, Ed.D. is the founder of Create-osity and currently serves as NSTA

District XIV Director. She is a former STEAM Coordinator and NASA Curriculum

Specialist. Her career is dedicated to vision that: No dream be deferred and no potential unrealized. Follow her on Twitter @createosity

Laura Cotter is the Outreach Education Senior Manager at Discovery Gateway

Children’s Museum. She has a degree in chemistry from the University of Utah. She

serves on the Board of the Utah Science Teachers Association, on the NSTA committee

for Research in Science Education.

Guest blog post by Wendi Laurence and Laura Cotter

One of my favorite things is discovering new people who can become partners in elementary science programming. While sometimes it is very hard to find those amazing partners; this is a short story about stumbling into one of those partnerships.

What’s Your Story?

By Korei Martin

Posted on 2019-07-16

Guest blog post by Anne Lowery

As the traditional school year winds down, it is time to bring explorations to an end or at least to a good stopping place. One of the best ways to signal an end or a transition is through science storytelling.

This approach has many of the science and engineering practices embedded into it, including but not limited to:

Analyzing and Interpreting Data

Constructing Explanations and Designing Solutions

Engaging in Argument from Evidence

Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information

Science storytelling is also an opportunity to turn study into action and have your students work to improve their own community as they tell a story. The possibilities are endless. Your students could write a story from the perspective of the researcher (themselves), or tell the story from the perspective of the subject of the exploration. They could also use their exploration as a tool to change actions in the community. They can write a song, create a letter campaign, design a video, or talk to community leaders.

By revisiting their work in a slightly different format, they solidify their own learning and begin to see how different learnings are interconnected. By writing it in a fictional format, with characters, students can reach people’s emotions– a surefire way to improve the odds of people remembering.

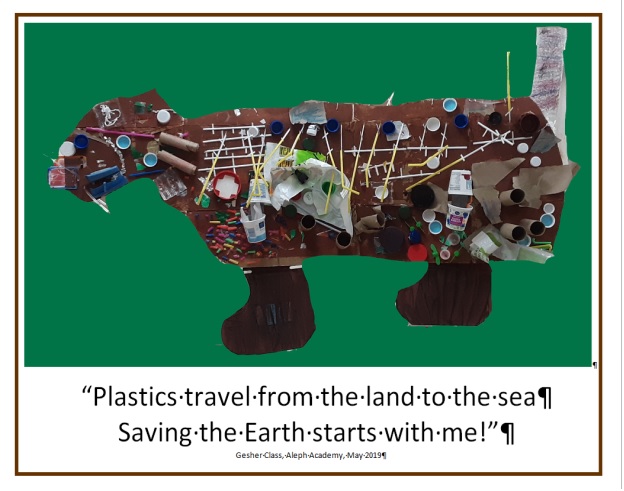

As an example, my students have been studying mountain lions and habitats this year. They noticed that land pollution is a problem with mountain lions, among other land animals. My students decided to focus on using their mountain lion knowledge to create a mountain lion out of trash. Then they wrote a simple chant to go with the mountain lion because, said one of my students, “everyone remembers things better if it’s a song.”

Another student pointed out we needed to write a story to go with our trashy mountain lion. As that student points out, when people imagine themselves in stories, they remember those stories.

Science storytelling has the potential to make your students’ research available to the public as well as having your students use their work to examine a real-world problem they have identified. Through such storytelling and action, your students leave your class not only with knowledge gained during the year but also with the mindset that they are scientists too.

What story are your students going to tell today?

This is a poster created from a 3D art installation created by PreK students. The shape of the mountain lion emphasizes the pollution threat to land animals. The plastics inserted through and covering the cardboard not only represent specific body parts of the animal but also are created from plastics commonly found on land.

Anne Lowry is a preK teacher at a Reggio inspired school in Reno, NV. Her students love to tell stories while discovering and enacting the science and engineering principles!

Guest blog post by Anne Lowery

As the traditional school year winds down, it is time to bring explorations to an end or at least to a good stopping place. One of the best ways to signal an end or a transition is through science storytelling.

This approach has many of the science and engineering practices embedded into it, including but not limited to:

Analyzing and Interpreting Data

Constructing Explanations and Designing Solutions

Engaging in Argument from Evidence

Ask a Mentor

Emoji Chemistry

By Gabe Kraljevic

Posted on 2019-07-13

Chemistry is not my strength. Any hints or resources for teaching chemical equations at a basic level?

Chemistry is not my strength. Any hints or resources for teaching chemical equations at a basic level?

— M., Maryland

I find it useful to demystify why we use chemical equations.

A chemical equation is simply a communication tool. It similar to using emojis in place of writing words. Instead of emojis, chemists use a periodic table and other standard symbols to communicate what is happening when particles of matter interact. Every scientist in the world knows this shorthand, overcoming language barriers. It is the language of chemistry.

Just like when learning a language, students need to learn basic vocabulary. Before teaching chemical equations, review some basic terminology: atoms, molecules, chemical change, and chemical formulas. Then move on to teaching the notations used in writing out a chemical equation.

A chemical equation is a “recipe” with ingredients, instructions, and expected results. Many recipes have the same ingredients, but the proportion of each determines whether you get a pancake, scone, or loaf of bread. Likewise, a balanced chemical equation gives the exact proportions of reactants to create the expected products. There are actually more details in a chemical equation than a recipe—the symbols indicate exactly how the atoms rearrange, form new bonds and create new products.

In addition to searching NSTA’s The Learning Center, resources at these sites can help teach chemical equations:

American Chemical Society

American Society of Chemistry Teachers

PhET Colorado Simulations

Hope this helps!

Image credit: Chemical & Engineering News

Chemistry is not my strength. Any hints or resources for teaching chemical equations at a basic level?

Chemistry is not my strength. Any hints or resources for teaching chemical equations at a basic level?

— M., Maryland

I find it useful to demystify why we use chemical equations.

Ed News: How to Engage All Students in STEM

By Kate Falk

Posted on 2019-07-12

This week in education news, CTE pathways prepare students for the rigors of STEM careers by giving them foundational skills and allowing for a broader interpretation of STEM; new report finds that 32% of teachers with one year or less of teaching experience have a non-school job over the summer break; study finds that the home literacy environment may influence the development of early number skills; and teachers around the world are using virtual reality to overcome barriers of physical distance and give their students a first-person view of the changes scientists are observing in remote areas.

How to Engage All Students in STEM

Early in their school careers, students see STEM pathways as desirable but then change their minds: 60 percent of high school students who start out interested in STEM careers lose interest by their senior year. And too many of those who are interested do not have the skills that are needed: A study by the Business-Higher Education Forum found that only 17 percent of high school students are both interested in STEM and proficient enough in math to succeed. Read the article featured in Education Week.

About One-In-Six U.S. Teachers Work Second Jobs – And Not Just in the Summer

Classes have ended for the summer at public schools across the United States, but a sizable share of teachers are still hard at work at second jobs outside the classroom. Among all public elementary and secondary school teachers in the U.S., 16% worked non-school summer jobs in the break before the 2015-16 school year. Notably, about the same share of teachers (18%) had second jobs during the 2015-16 school year, too, according to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). Read the article by the Pew Research Center.

Preschoolers Who Practice Phonics Show Stronger Math Skills, Study Finds

Young children who spend more time learning about the relationship between letters and sounds are better at counting, calculating, and recognizing numbers, a new study has found. Read the article featured in Education Week.

Report: More States Pursuing Innovative Assessment Models

Giving interim student assessments for accountability purposes — instead of waiting until spring when it’s too late for teachers to adjust their instruction — could “discourage weeks of pretest preparation” and provide schools with more useful feedback. But there might also be resistance to shifting curriculum and pacing during the school year, and teachers would need support in using the results. That’s one of the topics covered in a new “State of Assessment” report from Bellwether Education Partners. Read the brief featured in Education DIVE.

Elementary Education Has Gone Terribly Wrong

In the early grades, U.S. schools value reading-comprehension skills over knowledge. The results are devastating, especially for poor kids. Read the article featured in The Atlantic.

Virtual Field Trips Bring Students Face-To-Face with Earth’s Most Fragile Ecosystems

Teachers say first-person environmental experiences engage learners and foster empathy. Read the article featured in The Hechinger Report.

Requiring School to Teach Climate Change Risks Backlash in Oklahoma

Melissa Lau is preparing for the coming school year. She teaches 6th grade science in Piedmont, just northwest of Oklahoma City. Lau says she has been educating her students about the connection between fossil fuel combustion and climate change for three years, though she isn’t required to. Oklahoma’s K-12 science standards are based in part on the Next Generation Science Standards, national guidelines developed in 2013 that recommend teaching the concept in sixth grade, but Oklahoma left it out. Read the article featured on KOSU.org.

Stay tuned for next week’s top education news stories.

The Communication, Legislative & Public Affairs (CLPA) team strives to keep NSTA members, teachers, science education leaders, and the general public informed about NSTA programs, products, and services and key science education issues and legislation. In the association’s role as the national voice for science education, its CLPA team actively promotes NSTA’s positions on science education issues and communicates key NSTA messages to essential audiences.

This week in education news, CTE pathways prepare students for the rigors of STEM careers by giving them foundational skills and allowing for a broader interpretation of STEM; new report finds that 32% of teachers with one year or less of teaching experience have a non-school job over the summer break; study finds that the home literacy environment may influence the development of early number skills; and teache

Encouraging Creativity in STEM Class

By Debra Shapiro

Posted on 2019-07-10

Creativity often may be overlooked in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM), but STEM teachers are finding ways to make their lessons and courses innovative and encourage their students to be creative. For example, Emily Faulconer, assistant professor of math, physical, and life sciences at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach, Florida, says, “I challenge my students to summarize a concept in the form of a haiku…It helps them with vocabulary and thinking through the process, and gets students thinking outside the box…Haiku is a literary device, and easy to infuse.”

Faulconer cites “a recent interest in humanistic STEM at Embry-Riddle” that is supporting the infusion of the humanities into STEM courses. “It helps students view the sciences more broadly. They can look at science from other angles,” she contends.

As an online instructor, Faulconer posts haikus—her students’ and her own—in the discussion forum, and they’re not assessed because “the rubric grades on how students engage; it doesn’t have to be on the haiku. Students are assessed on one initial post and two reply posts [and giving] accurate responses,” she points out. While not all students contribute haikus, “the students think haiku is fun, and they comment on them. I enjoy reading them and so do they,” she relates.

“We’ve been doing infusions of other disciplines into science/STEM,” Faulconer continues. As the result of a research project on students’ perception of connections between the Introduction to General Chemistry 1 course and other STEM disciplines; the course and non-STEM disciplines; the course and their future careers; and the course and their academic degree, Faulconer and her science colleagues have changed the course’s module titles, “[leaning] more on other disciplines to make the modules sound more engaging,” she reports.

For instance, the course’s Introduction to Chemistry module has become Bacon and Gunpowder. “Philosopher Roger Bacon was the first European to develop a formula for gunpowder. [The new title] shows how important math is, which is taught in introductory courses,” Faulconer contends.

Solubility and Intermolecular Forces in Oxidation is now Water, Water, Everywhere because understanding “solubility and intermolecular forces in the context of water [makes sense because] so many reactions occur in aqueous environments,” she maintains.

And Solution Chemistry has become The Liquidation of Witches. “The phenomenon is from The Wizard of Oz, [when the Wicked Witch says,] ‘I’m melting!’ But she didn’t melt; she might have dissolved, but not melted. In the movie, she smokes when ‘melting.’ Smoke is suspicious; it was a chemical reaction,” Faulconer explains.

Last year, Faulconer and another Embry-Riddle professor created an interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary science course called Science of Flight. “Students are assessed on all subjects: biology, chemistry, environmental science, geology, and physics. It’s a general education course, [created] to give non-science students more interesting options. It’s a really popular class and is now running multiple sections online. Student feedback is positive,” Faulconer reports.

“I enjoy finding the interdisciplinary connections,” she relates. “The College of Arts and Sciences is so broad! It’s easy to stay siloed and not reach out to colleagues. This has encouraged me to work more closely with instructors with whom I haven’t worked before. Now they’re asking me about the science slant to, for example, Edgar Allan Poe and his possible death by carbon monoxide poisoning.”

Linking Robotics and Physics

“I am teaching Conceptual Physics and Robotics together [to first-year high school students] during the same class period. That has compelled me to be creative, searching for ways to link robotics and concepts in physics,” says Kathy Snyder, science and math teacher at Mary Help of Christians Academy in North Haledon, New Jersey. “The current project students are working on takes a jigsaw approach (experts in physics and robotics), with each team comprised of one member from each class.”

Snyder challenged student teams to “identify the key issues to enhancing ROV [remotely operated vehicle] design based on depth-pressure, kinematic, and dynamics to better gather scientific data in deep ocean trenches.” She told students, “In addition to building a model to scale, [you] will identify financial issues, research and [develop], prototype, and market for [your] device. [You] will present [your] models and needs for financing to instructors at our school in a Shark Tank–style event.”

Snyder says she developed the idea for the project when she read an article about Jason and Medea, ROVs designed and built by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s (WHOI) Deep Submergence Laboratory. She also was inspired by “research vessels that had gone to the bottom of the Mariana Trench” in the Pacific Ocean in record-breaking deep dives. Snyder cites WHOI’s Dive and Discover website (https://divediscover.whoi.edu) as a resource in creating the project.

“Each team’s underwater ROV must be better than…[Jason and Medea],” Snyder instructed students. To accomplish this, the robotics partner’s primary job is to “assess the current weaknesses of Jason and Medea,” she explains. Students’ models also “must go deeper than any previous ROV,” including the ones that traveled to the depths of the Mariana Trench, and students must “describe the way [their model] handles the pressure challenges of increasing depth,” which is the physics partner’s primary job, she relates.

“Some students are new to cooperative groups. It’s interesting to see them move from the grumbling stage to beginning to understand,” Snyder observes. “Both the [physics and robotics students] had a cursory knowledge of their own disciplines, but I encourage them to share their strengths…We do an engineering talk to share ideas.”

While not all of the students “have been challenged to integrate knowledge from multiple disciplines in elementary and middle school, the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) encourage critical thinking and problem solving. This approach is new for many students, [but this] is the way I’ve always taught,” Snyder relates. Her students “are getting comfortable with not knowing the answer” immediately, she adds. Along the way, she did “mini-lessons” on concepts students didn’t know, such as “scale models, for example: 2-D to 3-D,” she explains.

Part of her assessment of her students, she notes, includes whether “groups function effectively. Do they follow their agenda? What did they do when someone was absent, or when someone didn’t do their work?” During their presentations, students were graded on things like “eye contact, enthusiasm, and answering questions that they weren’t prepared to answer,” she relates.

“Giving them choices [about how to design their models] made [the project] more fun,” Snyder concludes. One team constructed their model from LEGO® toy building bricks, for example.

Using Play and the Arts

Gigi Carunungan, chief learning architect of Playnovate—an offline and online science, technology, engineering, art, and mathematics learning company for K–8—incorporates play and the arts in science teaching. She developed the Helical Model of Learning, which has five stages: Play, Explore, Connect, Imagine, and Remember. In a science module on germs, for example, third graders start by playing Tag with glitter of various colors attached to their hands with lotion. They spread “germs” by tagging their classmates and leaving glitter of mixed colors on their arms. (Alternatively, students could wear old clothing and aprons that could be tagged, Carunungan adds.)

“The game becomes a way to equalize the playing field because every student wants to play it, so everyone participates,” Carunungan maintains. “The rules are really about creating a socially interactive and physical dynamic,” she explains, because when students run around and tag one another, their arms now contain various colors, and the colors are blended. During the reflection time, “the teacher says, ‘That is like transmitting germs to one another,’” and offers no further explanation because the teacher is using the game as the phenomenon, she points out.

“Students remember this because it’s emotional. Emotional memory is more powerful than content memory in this case because the students have so much fun,” Carunungan contends.

In the next game, groups of students shoot water pistols at targets at various distances from them and observe the results. During reflection time, says Carunungan, students reach the understanding that the closer they were, the easier it was to hit the target. “The teacher says, ‘This is like [transmitting] germs. The closer you are, the more likely you’ll get them.’ The teacher is also showing students how to analyze data.”

In the module’s Connect phase, the teacher creates a graph of the length of students’ absences due to illness and the symptoms they experienced. Students learn how symptoms can be both the same and different for various people. After discussion, the teacher then explains what the word symptoms means. “Students understand the concept before the word. The concept is based on what they say [during the discussion],” she reports.

This activity “helps students develop a scientific mindset because they look at evidence, patterns, and variables,” Carunungan observes. The activity is done in the Connect phase because the graph “connects to real-world experiences from students’ own lives…[They are also] using data to make conclusions.”

Students then create their own graphs using data from students in other classes. Back in their classroom, they are assigned to small groups and present the data they gathered. Each group merges the data into one graph. “This is what scientists do: Collect samples from different places and compare and analyze and synthesize,” says Carunungan. The teacher can then connect this phenomenon to the work of microbiologist Louis Pasteur.

In the Imagine stage, students use modeling clay to create their own “germs” for a Germs Museum. Then students create posters on avoiding germs and staying healthy and hang them around the school.

When this module has been taught, “there is a jovial atmosphere in the classroom,” Carunungan recalls. “Creativity is cultivating an atmosphere in the classroom [in which] learning is about curiosity, connecting, and figuring out, and the students can get excited [about learning].”●

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2019 issue of NSTA Reports, the member newspaper of the National Science Teaching Association. Each month, NSTA members receive NSTA Reports, featuring news on science education, the association, and more. Not a member? Learn how NSTA can help you become the best science teacher you can be.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

Creativity often may be overlooked in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM), but STEM teachers are finding ways to make their lessons and courses innovative and encourage their students to be creative.

Ed News: What Does ‘Career Readiness’ Look Like in Middle School?

By Kate Falk

Posted on 2019-07-08

This week in education news, California schools preparing to ramp up course offerings and equip teachers to lead computer science courses; teaching students together and having them help one another learn may have more benefit to them and society than separating them by abilities; President announces the recipients of the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers; 2/3rds of American employees regret their college degrees; schools across the U.S. are grappling with how to incorporate the study of climate change into the classroom as its proximity and perils grow ever more apparent; and ‘improvement science’ helps school districts succeed at new initiatives.

As California Seeks to Add More Computer Science Courses, Teachers Are Answering the Call

As California pushes to increase access to computer science education for K-12 students, schools across the state this summer are preparing to ramp up course offerings and equip teachers to lead computer science courses. Read the article featured in EdSource.

Does Education Focus Too Much on Individual Achievement?

Educators can learn valuable lessons about the purpose and ultimate impact of education on society as a whole from the experiences of veteran African American teachers, who have historically viewed schools as a “public good to expand citizenship, equity, and collective responsibility” rather than an “engine for individual social mobility,” Kristina Rizga, author of “Mission High: One School, How Experts Tried to Fail It, and the Students and Teachers Who Made It Triumph,” contends in an article for The Atlantic. Read the brief featured in Education DIVE.

President Donald J. Trump announced the recipients of the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE). The PECASE is the highest honor bestowed by the United States Government to outstanding scientists and engineers who are beginning their independent research careers and who show exceptional promise for leadership in science and technology. Read the press release.

Two-Thirds of American Employees Regret Their College Degrees

A college education is still considered a pathway to higher lifetime earnings and gainful employment for Americans. Nevertheless, two-thirds of employees report having regrets when it comes to their advanced degrees, according to a PayScale survey of 248,000 respondents this past spring recently released. Read the article featured on CBSNews.com.

Teaching Global Warming in a Charged Political Climate

Their training doesn’t cover it, many textbooks don’t touch it, but teachers are taking on climate change anyway. Read the article featured in the Hechinger Report.

What Does ‘Career Readiness’ Look Like in Middle School?

School districts are pushing career exploration into middle and lower grades, convinced the preparation necessary for tomorrow’s jobs needs to begin earlier. Read the article featured in the Hechinger Report.

Taking Teacher Retention in the Summer Months

Administrators can take advantage of the summer months and build a good work environment by showing appreciation for teachers. Simple gestures go a long way towards keeping teachers connected and excited to return in the fall, Tracey Smith, principal of Brookwood Elementary in Georgia, writes for eSchool News. Read the brief featured in Education DIVE.

A Plan for Supporting New Initiatives

An approach to problem-solving called improvement science may give district and school initiatives a better chance at succeeding. Read the article featured in edutopia.

Stay tuned for next week’s top education news stories.

The Communication, Legislative & Public Affairs (CLPA) team strives to keep NSTA members, teachers, science education leaders, and the general public informed about NSTA programs, products, and services and key science education issues and legislation. In the association’s role as the national voice for science education, its CLPA team actively promotes NSTA’s positions on science education issues and communicates key NSTA messages to essential audiences.

This week in education news, California schools preparing to ramp up course offerings and equip teachers to lead computer science courses; teaching students together and having them help one another learn may have more benefit to them and society than separating them by abilities; President announces the recipients of the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers; 2/3rds of American employees

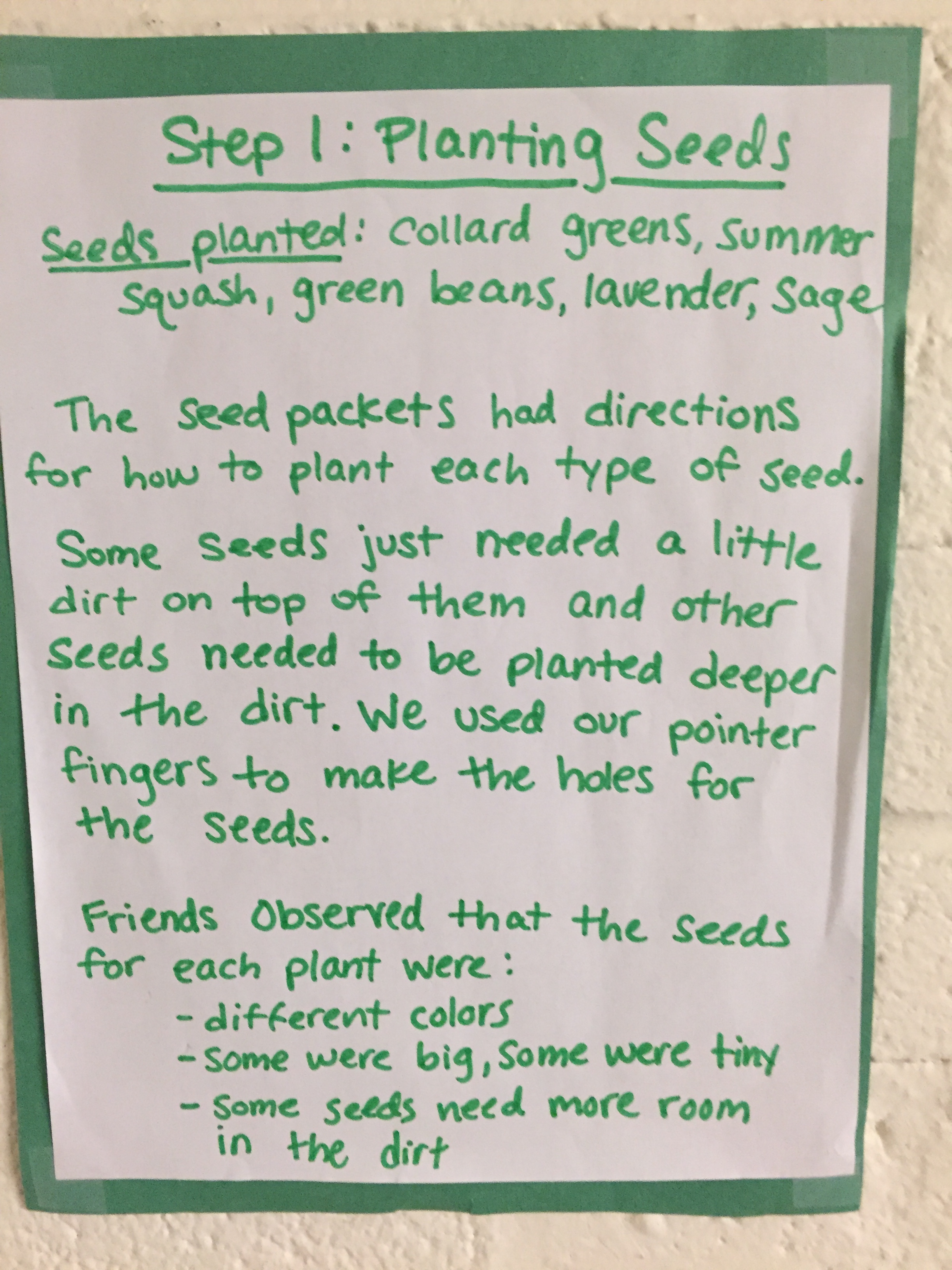

Summer seed planting

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2019-07-07

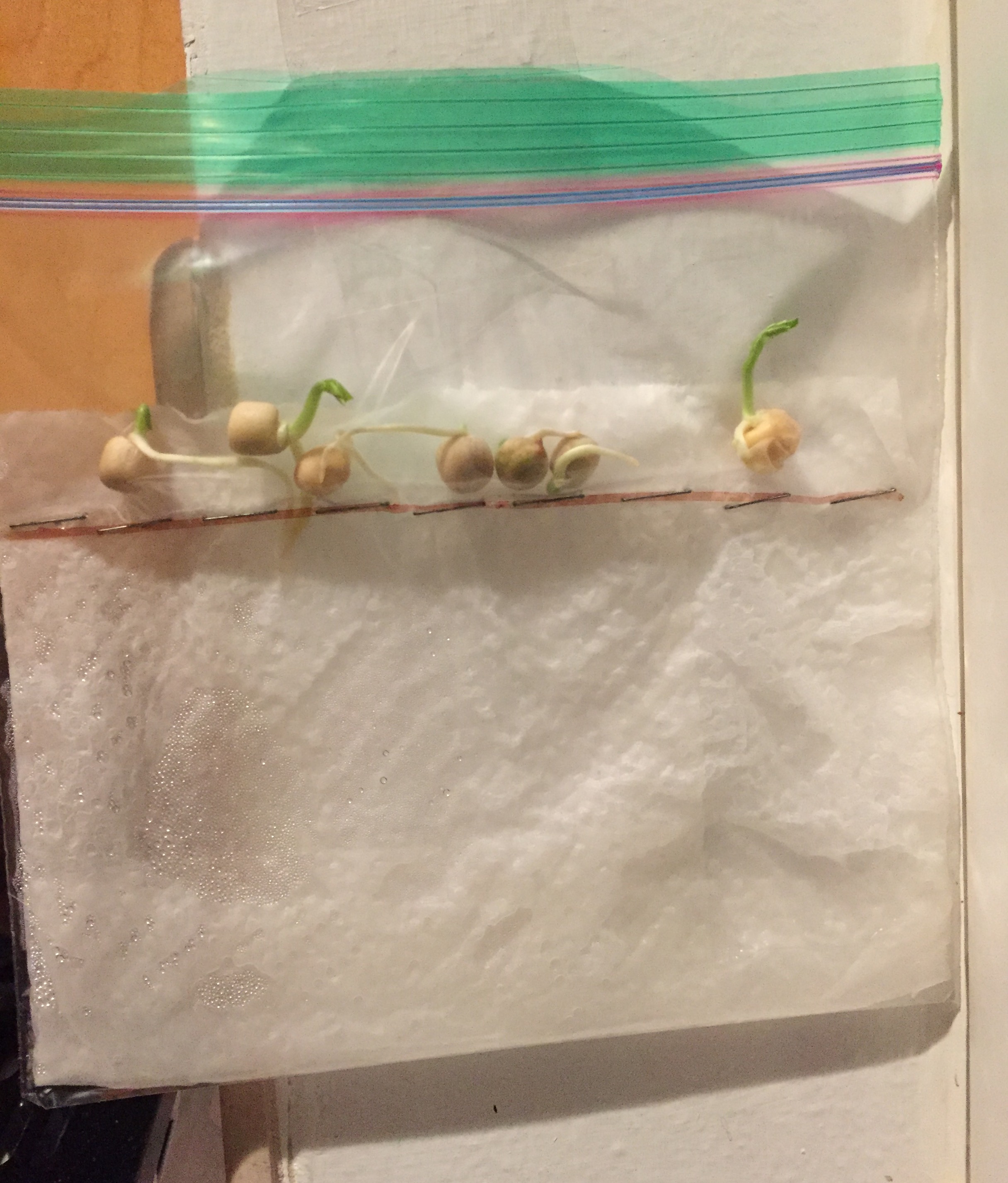

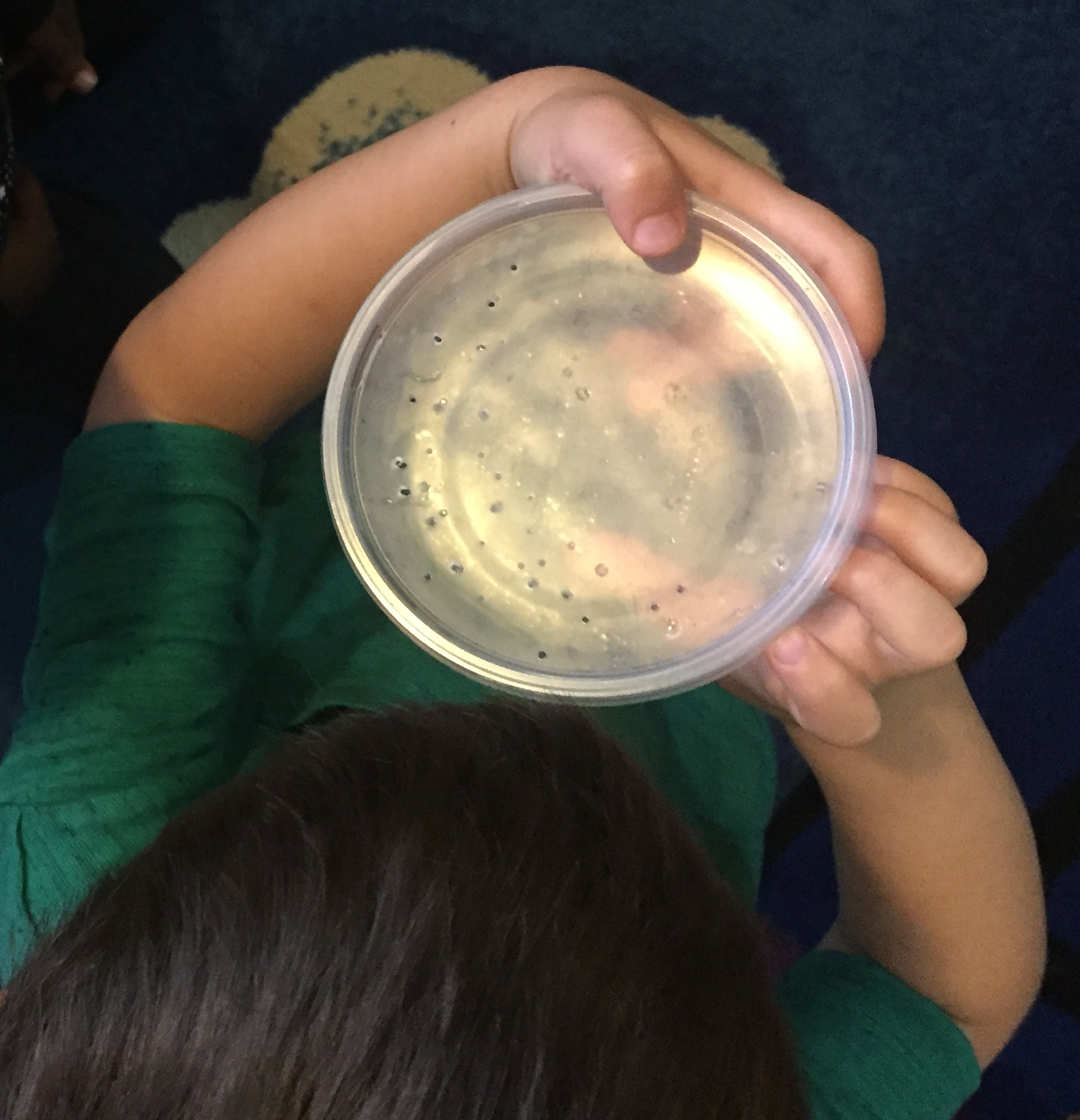

Some plants can be started from seed in the garden in midsummer’s warmest weather and still grow plants that reach maturity before the first killing frost in the fall. With multiple experiences handling and planting seeds children grow their understanding of the function of seeds. “Plants also have different parts (roots, stems, leaves, flowers, fruits) that help them survive, grow, and produce more plants” (NRC, page 144). In the July 2018 Early Years column I wrote about investigating seed sprouting with children to begin learning about plants’ needs for sustaining growth, part of the NGSS Disciplinary Core Idea, LS1.C: Organization for matter and energy flow in organisms.

To learn which seeds to plant outdoors now, ask the families of children attending your program in summer to share their gardening experiences. Other places to find experienced or expert gardeners include the local farmers’ market, the county extension service, Master Gardener program, or a high school National FFA Organization. Consult seed planting calendar guides from local extension services and seed companies and have children help determine which seeds to start in which month in your locality.

Here are a few examples of such resources:

Alabama Cooperative Extension System, Alabama Vegetable Garden Planting Chart. https://www.aces.edu/blog/topics/lawn-garden/planting-guide-for-home-gardening-in-alabama/

Farm Advisor UC Cooperative Extension, Vegetable Garden Planting, Planting Guide for San Diego County by Vincent Lazaneo. https://www.mastergardenerssandiego.org/Vegetable%20Planting%20Guide1.pdf

North Carolina State Extension Table 1. Garden planting calendar for vegetables, fruits, and herbs in Central North Carolina. https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/central-north-carolina-planting-calendar-for-annual-vegetables-fruits-and-herbs

Purdue Extension, Indiana Vegetable Planting Calendar by Michael N. Dana and B. Rosie Lerner. https://ag.purdue.edu/hla/pubs/HO/HO-186.pdf

Planting seeds in containers indoors makes it easy to view the sprouting process and tiny seedling structures. If seedlings get enough light from the sun, or from “grow lights,” they may be strong enough to transplant into the garden.

Children can help plan if they have time and experiences to understand the needs of plants.

Garden planning steps documented by teacher Sue Nellor

With the average first killing frost in mind, I’m planning to plant bush bean seeds in the soil in mid August, and put in some collard seedlings to overwinter. The beans take from 50-60 days to maturity—enough time for children in a year-round program to plant, tend, harvest, and taste their own produce. Hopefully the collards will host the eggs of Cabbage white butterflies (Pieris rapae), and when they hatch, feed the larvae, providing an observational experience for children next spring. See the April 2007 Early Years column (free for non-members!) for more on the relationship between Pieris rapae and plants of the Cruciferae (Brassicaceae) family.

Some plants can be started from seed in the garden in midsummer’s warmest weather and still grow plants that reach maturity before the first killing frost in the fall. With multiple experiences handling and planting seeds children grow their understanding of the function of seeds.

Split Decision

By Gabe Kraljevic

Posted on 2019-07-06

How does one model a 5E lesson plan for each topic covered when teaching a split grade level?

How does one model a 5E lesson plan for each topic covered when teaching a split grade level?

— C., Illinois

Split classes can be very challenging, particularly if they have drastically different curricula. However, I believe you can manage better if your lessons use a three-dimensional approach. Instead of content topics, you can structure your 5E (Engage-Explore-Explain-Elaborate-Evaluate) lessons around a cross-cutting theme, a core idea, or a scientific practice common to all science curricula. What would differ in your class is what the students “Explore” about the common theme, idea or practice. I believe the core ideas in each subject area would be the easiest to focus on but it would be powerful to wrap a lesson around a science practice like engaging in arguments based on evidence.

Have the students from both grades share what they learned and ask questions that arose from their explorations. This flows nicely to the “Explanation” and “Elaboration” stages of a 5E lesson. Consider pairing students across the grades and incorporating some peer teaching and evaluation.

You can structure formative and summative evaluations around their understanding of the themes, core ideas, and practices by how they apply the knowledge of the topics from the lesson. You might be able to create tests that ask the same questions but would have slightly different answers depending on the exploration used in each grade level.

Please visit NGSS@NSTA (https://ngss.nsta.org/) for ideas, lessons, and workshops involving 3D learning.

Hope this helps!

Image credit: Kaspar Lunt via Pixabay

How does one model a 5E lesson plan for each topic covered when teaching a split grade level?

How does one model a 5E lesson plan for each topic covered when teaching a split grade level?

— C., Illinois

Observing children observing bees

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2019-07-05

Some children feel a kinship with all kinds of living things. They may reach out to touch a bumble bee on a flower or hug a worm too tightly. Touching a bee may be fine if the temperature is so cold it has paused on the flower overnight waiting for morning’s warming sun but I do want children to be aware of the potential hazards of handling small animals.

Promoting caution but not fear while observing small animals supports all children. We can plan opportunities for observation, where children whose affinity for living organisms is still developing can see while maintaining a comfortable distance. Confining small animals in containers for brief periods of observation is one way to provide that distance. Some children eagerly look at books about animals, gaining a familiarity that can make first hand experiences more comfortable.

Observing children, and thinking about what their actions tell us they understand, is the beginning of formative assessment—assessment that informs the direction and progress of teaching. Documenting other ways of knowing children’s thinking, such as, their drawings or conversations during book read-aloud, as well as our observations, guides our next steps in planning lessons. Our collected knowledge and documentation of children’s actions, thinking, and work becomes formative assessment when we “use the information to inform instruction, plan interactions that scaffold learning, and communicate children’s progress to them, their families, and others” (Riley-Ayers in Bohart & Procopio 2018).

Formative assessment systems can be very individual and a strength-based way of documenting and identifying children’s development. Instead of saying, “This child is afraid of bees,” I might say, “This child is cautiously observing bees while maintaining a distance that feels comfortable.” Reviewing the formative assessment documentation supports children’s reflection on their ideas. Hoisington (2016) writes, “Get ALL of the children’s science ideas out on the table, Provide opportunities for children to investigate their ideas, Facilitate children’s reflection on the evidence.” Follow up activities with discussion to find out what children think they know about how animals get the food and other things they need. The NGSS Appendix E: Progressions Within the Next Generation Science Standards describes how children’s beginning understandings become more sophisticated as they grow and learn.

References

Riley-Ayers, Shannon. 2018. Introduction to Spotlight on Young Children: Observation and Assessment by H. Bohart and R. Procopio. NAEYC.

Some children feel a kinship with all kinds of living things. They may reach out to touch a bumble bee on a flower or hug a worm too tightly.