Legislative Update

ESSA Webinar and Rally on Capitol Hill

By Jodi Peterson

Posted on 2016-05-20

Update on Every Student Succeeds Act

Almost 200 teachers and science leaders tuned into the NSTA Learning Center webinar last week on the new federal education law (ESSA), co-hosted by NSTA and the National Science Education Leadership Association (NSELA). You can find the powerpoint from the webinar here and learn more about the new federal education law here.

As states gear up for implementation of ESSA, more heated debate around the regulatory language for ESSA’s supplement-not-supplant provision, which says that federal Title I funds for low income students must be in addition to, and not take the place of, state and local spending on K-12. (Drafts of the regulations are in circulation, however the Department of Education (ED) is expected to officially release regulations for comment on accountability, state plans, supplement-not-supplant and assessments this summer.) Education Week reports that a recent Congressional Research Service report on ED’s proposed regulations are outside of the statutory language that ESSA allows.

Republicans (and unions) are concerned that ED officials would violate the new law by requiring districts to use a school-level test of expenditures to show compliance with supplement-not-supplant, which could ultimately mean monitoring teacher salaries when calculating how much schools receive. Many Democrats believe this provision will provide an important tool to ensure the new federal law provides equity. Senator Lamar Alexander, a chief architect of the new federal education law, recently said that the Education Department has been “deceitful” in trying to force equity through implementation of the new education law.

Ed Groups Rally for ESSA Title IV Block Grants

NSTA joined over 75 organizations last week for a press conference and rally on Capitol Hill urging Congressional appropriators to fully fund Title IV, Part A of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

Congress authorized this flexible ESSA block grant, known as Student Support and Academic Enrichment Grant, at $1.65 billion for FY 2017. Congressional appropriators are now working to provide funding amounts for this and other FY2017 federal education programs. The Title IV grants will provide funding to districts for activities in three broad areas:

1) Providing students with a well-rounded education (e.g. college and career counseling, STEM, arts, civics, IB/AP)

2) Supporting safe and healthy students (e.g. comprehensive school mental health, drug and violence prevention, training on trauma-informed practices, health and physical education) and

3) Supporting the effective use of technology (professional development, blended learning, and devices).

Specifically, in regards to the use of Title IV A funds for STEM, districts and states can use grant monies to expand high-quality STEM courses; increase access to STEM for underserved and at risk student populations; support the participation of students in STEM nonprofit competitions (such as robotics, science research, invention, mathematics, computer science, and technology competitions); provide hands-on learning opportunities in STEM; integrate other academic subjects, including the arts, into STEM subject programs; create or enhance STEM specialty schools; integrate classroom based and afterschool and informal STEM instruction; and expand environmental education.

Myra Thayer, Prek-12 Science Coordinator, Fairfax County Public Schools, was NSTA’s guest speaker at the press event. She told participants that “Providing students with hands-on learning opportunities in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM), increasing access for underserved students, and integrating afterschool STEM experiences with classroom-based learning will improve instruction and student engagement in these fields. It’s critical that Congress fully fund the ESSA Title IV-A, Student Support and Academic Enrichments Grants, so that all students have access to quality STEM programs, and to a variety of health and safety programs, diverse academic courses, and modern technology.”

At the press event/rally the group also released individual letters from state and local groups in Minnesota, Missouri, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Washington, seeking full funding for this grant.

In addition to seeking funding for Title IVA at $1.65 billion NSTA, the STEM Education Coalition and 85 other organizations, is asking Congress to

- Provide $2.250 billion for the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) Title II Supporting Effective Instruction State grants. This program provides support for teacher quality improvement initiatives, including professional development and teacher leadership.

- Support the proposal of $100 million for the new Computer Science for All Development Grants.

- Provide $10 million for a STEM Master Teacher Corps which was authorized through Section 2245 of ESSA. This program would help cultivate teacher leaders in STEM subjects and promote the sharing of best practices across the teaching professions.

These programs will be part of the FY2017 Labor, HHS, and Education appropriations bill. Advocates expect to see some Congressional action on this bill in mid-June. Stay tuned.

Jodi Peterson is Assistant Executive Director of Legislative Affairs for the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) and Chair of the STEM Education Coalition. e-mail Peterson at jpeterson@nsta.org; follow her on Twitter at @stemedadvocate.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

Creative Writing in Science

By Carole Hayward

Posted on 2016-05-19

Would you like to inspire students to be better writers while you incorporate new strategies into your teaching to assess their scientific understanding? Katie Coppens’ new NSTA Press book, Creative Writing in Science, provides engaging literary exercises that use the world around us to inspire. Designed for grades 3–12, the book offers fiction, poetry, and playwriting prompts that help students increase both their writing skills and their science knowledge.

Would you like to inspire students to be better writers while you incorporate new strategies into your teaching to assess their scientific understanding? Katie Coppens’ new NSTA Press book, Creative Writing in Science, provides engaging literary exercises that use the world around us to inspire. Designed for grades 3–12, the book offers fiction, poetry, and playwriting prompts that help students increase both their writing skills and their science knowledge.

Each writing lesson outlines foundational science knowledge and vocabulary and connects to the Next Generation Science Standards. The lessons also introduce language arts skills such as developing characters; writing conflict; and using personification, narrative voice, and other literary devices.

In the lesson “Travel Blog About the Digestive System,” students must apply their knowledge and vocabulary related to the human digestive system to compose a blog post from the perspective of a bit of food on a journey through the human body. Students will capture all of the twists and turns and use personification to convey this trip of a lifetime.

In another unique lesson, students are asked to imagine what life would be like if the KT asteroid had never hit. How would our landscape look and what organisms would be thriving today? Students must consider what role evolution would have played, and what animals might have become extinct. Would dinosaurs be here? Would humans still be roaming Earth?

Additional ideas to get students thinking creatively include writing comics, diary entries, songs, and letters from the point of view of the Moon, rocks, atoms, and more! The 15 lessons cover life science, physical science, Earth, space, and engineering.

This book is humorous and engaging, and your students will love approaching science from a new direction.

Want to get your creative juices flowing? Try the free chapter “Group Poem: Earth’s History.”

Check out Creative Writing in Science in the NSTA Press Store.

Follow NSTA

Would you like to inspire students to be better writers while you incorporate new strategies into your teaching to assess their scientific understanding? Katie Coppens’ new NSTA Press book, Creative Writing in Science, provides engaging literary exercises that use the world around us to inspire.

Would you like to inspire students to be better writers while you incorporate new strategies into your teaching to assess their scientific understanding? Katie Coppens’ new NSTA Press book, Creative Writing in Science, provides engaging literary exercises that use the world around us to inspire.

Start and end the year safely

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2016-05-18

Questions and discussions about safety are often seen in the NSTA e-mail listserves and discussion forums. Each month, columns on safety in the science classroom/lab are featured in NSTA’s Science Scope (Scope on Safety) and The Science Teacher (Safer Science), with occasional articles in Science and Children (Safety First). These columns are written by Ken Roy, Director of Environmental Health and Safety for Glastonbury Public Schools in Glastonbury, CT, and NSTA’s Science Safety Compliance Consultant.

Questions and discussions about safety are often seen in the NSTA e-mail listserves and discussion forums. Each month, columns on safety in the science classroom/lab are featured in NSTA’s Science Scope (Scope on Safety) and The Science Teacher (Safer Science), with occasional articles in Science and Children (Safety First). These columns are written by Ken Roy, Director of Environmental Health and Safety for Glastonbury Public Schools in Glastonbury, CT, and NSTA’s Science Safety Compliance Consultant.

These are must-reads for K-12 science teachers and school administrators, regardless of what grade level or science course you teach. And NSTA members have online access to them, regardless of which print journal you receive.

The 2015-16 columns speak to a variety of safety concerns:

- Safety in Science Instruction – A discussion of NSTA’s position paper on “Safety and School Science Instruction” (TST 2/16)

- Safety Acknowledgment Form for Earth and Space Science – Customize the acknowledgment form for different subjects

- Making the Grade on Safety – The value of lab safety assessments for students at the beginning of (and during) the year (SS 3/16)

- Preventing Allergic Reactions – Preventing and dealing with allergies in the classroom (S&C 12/15)

- Creating Latex-Safe Classrooms – Allergic reaction to latex materials (SS 4/16)

- Safety Picks Up “STEAM” – Considerations for engineering activities (S&C 2/16)

- Wired for Safety – Using electricity in science classrooms (SS 12/15)

- Don’t Bench Lab Safety – Suggestions for purchasing lab furniture (SS 11/15)

- Detoxing the Lab – Reduce risks of toxic substances in the classroom/lab (SS 9/15)

- Safer Science Kits – What to consider when adopting/using science kits (SS 10/15)

- Safety: Food for Thought – Food in the lab and other issues of cross-contamination (SS 7/15)

- Eyeing Safety (SS 2/16)

- Safer Science Outside the Classroom – What to consider when planning field trips or outdoor classes (SS 1/16)

- Safety in the Field – What to consider when planning field trips (TST 10/15)

- A Healthier Science Class – Preventing chemical hazards (TST 12/15)

- Handling Hazardous Waste (TST 9/15)

- Heightened Risks – Hazards when conducting activities on ladders, platforms, rooftops (TST 7/15)

- Preventing Alcohol-Based Laboratory Fires (TST 4/16)

- Safer Use of Toxic Chemicals (TST 3/16)

- Safer Reproductive Health in Science Labs – Protecting the health of students (and teachers). (TST 1/16)

Each month, Scope on Safety also includes a Q&A on a safety-related issue. If you’re looking for a science department discussion topic, choose an article relevant to your situation. For more on safety topics, go to NSTA’s SciLinks and use “safety” as the keyword.

Questions and discussions about safety are often seen in the NSTA e-mail listserves and discussion forums. Each month, columns on safety in the science classroom/lab are featured in NSTA’s Science Scope (Scope on Safety) and The Science Teacher (Safer Science), with occasional articles in Science and Children (Safety First).

Questions and discussions about safety are often seen in the NSTA e-mail listserves and discussion forums. Each month, columns on safety in the science classroom/lab are featured in NSTA’s Science Scope (Scope on Safety) and The Science Teacher (Safer Science), with occasional articles in Science and Children (Safety First).

NSTA Membership: It Opens the Door to Opportunity

By Guest Blogger

Posted on 2016-05-18

Membership in NSTA comes with a wealth of benefits. Although the most obvious benefit may be the regular appearance of Science Scope in your mailbox and NSTA Reports in your Inbox, membership encompasses far more. The ability to connect through list serves, interact with other middle school science teachers via the Learning Center forums, serve on a variety of NSTA committees and advisory boards, and apply for prestigious awards are some examples of additional NSTA member benefits. There is, however, one hidden member benefit that we consider to be priceless; it is the ability to carve deep and lasting friendships through the personal connections afforded by involvement with NSTA.

As veteran middle school science teachers, we began our individual professional relationships with NSTA many years ago while serving on the Toyota Tapestry Grant Judging Panel. Although the panel no longer exists, the friendship that evolved through our common experience has stood the test of time and serves as an example of NSTA’s unique ability to connect science educators with each other. We have overcome the physical distance that separates us and have strengthened our friendship through presentations made at NSTA conferences, by teaching short courses together, and by recently authoring a book for NSTA Press.

NSTA offers numerous venues for personal and professional growth that will afford you the ability to connect with like-minded peers. We know from experience that attending a NSTA conference will leave you recharged as a result of your contact with other science educators. You can maintain that conference energy through activity in one or more of NSTA’s social media platforms, which include Twitter, Facebook, and the middle school list serve (middleschool@list.nsta.org). If you have taught for less than five years, we recommend that you to apply for the Maitland P. Simmons Memorial Award (https://www.nsta.org/docs/awards/NewTeacher.pdf). This outstanding program provides a year of professional development that includes attendance at the NSTA national conference.

Get Involved and Grow as a Leader

Involvement in NSTA will also allow you to grow as a leader in your educational community. We encourage you to expand your relationship with NSTA by volunteering to serve on a NSTA committee or advisory board. Consider lending your expertise to the Committee on Middle Level Science Teaching or to the Science Scope Advisory Board. This is a great way to meet colleagues from across the nation while helping to drive decisions that will impact the organization.

If you are planning on attending an upcoming NSTA national or regional conference, submit a proposal for a session. Keep in mind, however, that proposals need to be submitted nearly a year in advance (http://www.nsta.org/conferences/sessions.aspx). Presenting in front of your peers will help you grow both professionally and personally. If your strengths lie in written communication, you may want to consider authoring an article for Science Scope. A great way to build your confidence and knowledge prior to submitting a manuscript is to offer to review for Science Scope. In the process, you will be providing a valuable service to NSTA while gaining an insider’s viewpoint regarding the publication process.

The path to greater involvement in NSTA is as varied as the numerous member opportunities available to you. Whether you choose to become more active at the conference level, develop your reviewing or writing skills, or to serve in a leadership capacity, your growth as a science educator will be profound and may lead to the greatest benefit of all: friendship.

Patty McGinnis teaches at Arcola Intermediate School in Eagleville, PA and is editor of Science Scope. Kitchka Petrova is currently a doctoral student at Florida State University in Tallahassee, Florida. Their book Be a Winner: A Science Teacher’s Guide to Writing Successful Grant Proposals allows readers to learn from veteran science teachers about the secrets to successful grant writing. Formatted as a handy workbook, this practical book takes you step by step through the writing process.

Join today and receive Science Scope, the peer-reviewed journal just for middle school teachers; connect on the middle level science teaching list (members can sign up on the list server); or consider joining your peers for Meet Me in the Middle Day (MMITM) at the National Conference on Science Education in Los Angeles in the spring of 2017.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

NGSS Workshops

- Discover the NGSS, San Diego, June 29–30

- NGSS Summer Institute, Reno, July 15

- NGSS Summer Institute, Detroit, Aug. 8

- Discover the NGSS, Fall 2016 & Spring 2017

2016 STEM Forum & Expo, hosted by NSTA

2016 Area Conferences

2017 National Conference

Minneapolis, the Place to Be for Science Education This Fall

By Guest Blogger

Posted on 2016-05-13

Join NSTA in Minneapolis this October 27–29, 2016, for our first area conference on science education. Our outstanding program will have something for science teachers of all subject areas and experiences. With featured speakers who will leave you inspired, to sessions that will give you more resources than you can possibly use, the upcoming NSTA Area Conference in Minneapolis is the place you need to be.

To help you make the most of the professional development opportunities available at the Minneapolis conference, the Conference Committee has planned the conference around three strands that explore topics of current significance, enabling you to focus on a specific area of interest or need.

Teaching Science in a Connected World

Students and teachers have access to many forms of technology. These technologies can be effective tools to access information, deliver instruction, communicate ideas, connect with people from around the world, and build professional learning networks. Educators attending these sessions will explore instructional materials, technologies and strategies for effective learning for students and adults, and responsible use of digital resources and processes.

STEMify Instruction Through Collaboration Across the Curriculum

STEM can be a powerful unifying theme across the curriculum and in many settings. STEM provides an opportunity for collaboration among teachers, disciplines, and schools, as well as postsecondary, informal education, and community partners. Educators attending sessions in this strand will explore models of integrated STEM education programs, learn strategies to productively STEMify lessons, and investigate how to effectively engage students.

Celebrating Elementary Science and Literacy Connections

Children are born investigators. Science is an engaging way to develop students’ skills in thinking creatively, expressing themselves, and investigating their world. Reading, writing, and speaking are inspired through science experiences. Educators attending these sessions will gain confidence in teaching science, learn strategies for literacy and science integration, and celebrate elementary science.

We hope to see you in Minneapolis in October! Save the date, line up your subs, and please check back here in early June for registration information.

Author Jean Tushie is a High School Biology Teacher and the MnSTA conference coordinator. As a former NSTA council and board member, Tushie is NSTA’s biggest cheerleader!

Author Jean Tushie is a High School Biology Teacher and the MnSTA conference coordinator. As a former NSTA council and board member, Tushie is NSTA’s biggest cheerleader!

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

5th Annual STEM Forum & Expo, hosted by NSTA

- Denver, Colorado: July 27–29

2016 Area Conferences

- Minneapolis, Minnesota: October 27–29

- Portland, Oregon: November 10–12

- Columbus, Ohio: December 1–3

National Conferences

- Los Angeles, California: March 30–April 2, 2017

- Atlanta, Georgia: March 15–18, 2018

- St. Louis, Missouri: April 11–14, 2019

- Boston, Massachusetts: March 26–29, 2020

- Chicago, Illinois: April 8–11, 2021

Follow NSTA

The last days of the school year

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2016-05-12

I’m looking for suggestions for what to do during the last week of school, after final exams are over. I teach high school chemistry. —T., Maryland

I’m looking for suggestions for what to do during the last week of school, after final exams are over. I teach high school chemistry. —T., Maryland

It’s hard to justify students (and parents) why students should come to school on the last days of the year, if all they do is watch videos, do busywork, talk to or text each other, have one study hall after another, or roam the halls. The last few days of the school year can be a gift of time for explorations and enrichment activities.

But the end of the year is a busy time for you, too. Your after-school time is probably spent on grading exams, evaluating projects, finalizing inventories, or preparing final grades. So the last thing you need is planning additional activities to keep students busy.

Here are some learning-related alternatives that won’t require a lot of preparation:

- My students enjoyed vocabulary games, such as variations on Jeopardy or A card sort or word splash is easy to put together. In science charades, each team creates a pantomime of a vocabulary term or science process for other students to figure out (it’s amazing what they can do with mitosis or Newton’s laws).

- Dig out those lab activities or online simulations you wanted to do during the year but didn’t have time.

- You could ask them to work in groups to come up with a “guide” for next year’s class –something like The Top 10 Things You Need to Know About Chemistry Class or Chemistry Class FAQs (and Answers). You could make this open-ended or you could give different topics to the groups (e.g., lab safety, study skills, lab procedures, difficult topics, or how to use a science notebook. You may need to model a few appropriate ideas before they start. The groups could share and debrief with each other, perhaps as a gallery walk. This could also be an informal evaluation survey, since you’ll get to see what they thought was essential or important enough to share. And be sure to share a composite list with your students at the beginning of next year.

- Have students try out a new technology tool or app. Assign an app to each group and ask them to demonstrate it and describe how it would (or would not) be useful for students in your class next year. You can be part of the audience.

I would be cautious about having students assist with lab cleanup or inventories. You would need to supervise both those who are helping you and those who are not. The liability may not be worth the extra help.

If grades are turned in, it may be hard to get students to participate in any activities, especially if students expected points that “counted” for every activity and they know that grades are calculated. You might also hear “But Mr. B gave us a study hall.” Be persistent. I suspect that most students would rather have a planned enjoyable activity to do (even though they might grumble about it).

A wise teacher once advised me to start planning for the last week during the first week of school. Take photos or videos of activities and equipment during each unit, and have students write captions for them at the end of the year. Prepare vocabulary lists ahead of time, or (better yet) have students make the lists in their notebooks.

Time is a precious commodity. We never have enough, so let’s not waste any of it.

I’m looking for suggestions for what to do during the last week of school, after final exams are over. I teach high school chemistry. —T., Maryland

I’m looking for suggestions for what to do during the last week of school, after final exams are over. I teach high school chemistry. —T., Maryland

Using museums, the community and playfulness to bring STEM concepts to life

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2016-05-10

Please welcome guest blogger, Brooke Shoemaker, who brings her museum education expertise to The Early Years blog. Brooke was a pre-k classroom educator at the Smithsonian Early Enrichment Center (SEEC) in Washington, D.C. for four years, before joining SEEC’s outreach arm, the Center for Innovation in Early Learning as the Pre-K Museum Education Specialist. You can read SEEC teachers’ reflections on their practice on the SEEC blog.

SEEC invites you to join them for a two-day seminar, “Play: Engaging Learners in Object Rich Environments,” on June 28th and 29th, to explore how to use play as a vehicle for engaging young children in the classroom, museum, and community.

As early childhood educators, we know play is important, but how can we utilize play to engage students in the classroom, museums, and the community? At the Smithsonian Early Enrichment Center, we playfully approach object-based learning to engage our young learners and help them make connections between concepts being taught and the world around them. Object-based learning represents a framework for teaching and learning that engages students in a process of understanding the world and its complexity through the study of objects.

This past fall, my co-teacher Tina Brimo and I decided to explore the topic of oceans with our class of three-year-olds because every time we walked through The Sant Ocean Hall at The National Museum of Natural History the children were full of questions about the animals and objects they saw. Tina and I wanted to present the science, technology, engineering and math concepts in the lessons playfully through hands-on, teacher-guided play, as well as unstructured, child-directed play opportunities, such as dramatic, and symbolic play.

This past fall, my co-teacher Tina Brimo and I decided to explore the topic of oceans with our class of three-year-olds because every time we walked through The Sant Ocean Hall at The National Museum of Natural History the children were full of questions about the animals and objects they saw. Tina and I wanted to present the science, technology, engineering and math concepts in the lessons playfully through hands-on, teacher-guided play, as well as unstructured, child-directed play opportunities, such as dramatic, and symbolic play.

To begin our exploration of oceans, we went to The Sant Ocean Hall where children’s curiosity was sparked, and created an ocean web graphic organizer to record questions that the students had, and wanted to learn about over the course of the unit. One of the questions that day was, “Why do seashells open up?”, so I knew we would have to learn about bivalves at some point during the unit! But how do you make a lesson about bivalves for preschoolers playful and engaging?

To begin our exploration of oceans, we went to The Sant Ocean Hall where children’s curiosity was sparked, and created an ocean web graphic organizer to record questions that the students had, and wanted to learn about over the course of the unit. One of the questions that day was, “Why do seashells open up?”, so I knew we would have to learn about bivalves at some point during the unit! But how do you make a lesson about bivalves for preschoolers playful and engaging?

The objectives for the bivalve lesson were to understand that bivalves are animals that have two shells that enclose them, which serve as protection, and that those two shells are symmetrical. To help make these concepts more concreate, I used a collection of seashells and two sculptures in the Hirshhorn Sculpture Garden on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

Dan Graham’s sculpture, For Gordon Bunshaft, was a perfect object to introduce the idea that bivalves are enclosed in two shells. We were able to sit inside the piece and pretend to be bivalves ourselves. We talked about how the walls of the sculpture made us feel safe and protected from the outside elements, just like the shells of a bivalve do.

Dan Graham’s sculpture, For Gordon Bunshaft, was a perfect object to introduce the idea that bivalves are enclosed in two shells. We were able to sit inside the piece and pretend to be bivalves ourselves. We talked about how the walls of the sculpture made us feel safe and protected from the outside elements, just like the shells of a bivalve do.

While sitting inside the sculpture I passed around the collection of bivalve shells, and the students made observations about the size, shape, and texture. We noticed that the shells’ hardness made them ideal for protection. Noticing and describing size, shape, and symmetry demonstrates a beginning understanding of geometry.

Then we turned our attention to Ellsworth Kelly’s sculpture, Untitled, to introduce the idea of symmetry. As the children observed the sculpture, they noticed that it looked like a circle folded in half, and that each half was exactly the same or symmetrical. The children explored the collection of shells again, this time putting two shells together. Children noticed that if two shells were mismatched, or asymmetrical, the shells left openings on the sides, however, symmetrical shells closed snugly, and therefore protected the bivalve. The class practiced their careful looking skills by playing a game to match shells to their symmetrical counterpart. To end the lesson the children used their fine motor skills to cut a shape out of a folded piece of paper, yielding a shape that was the symmetrical on both sides. They called these their bivalves, and had a blast making them open and close. The children gained early engineering understanding through examining how the symmetrical shells fit together, as well as learning about the mechanics of bivalves.

Then we turned our attention to Ellsworth Kelly’s sculpture, Untitled, to introduce the idea of symmetry. As the children observed the sculpture, they noticed that it looked like a circle folded in half, and that each half was exactly the same or symmetrical. The children explored the collection of shells again, this time putting two shells together. Children noticed that if two shells were mismatched, or asymmetrical, the shells left openings on the sides, however, symmetrical shells closed snugly, and therefore protected the bivalve. The class practiced their careful looking skills by playing a game to match shells to their symmetrical counterpart. To end the lesson the children used their fine motor skills to cut a shape out of a folded piece of paper, yielding a shape that was the symmetrical on both sides. They called these their bivalves, and had a blast making them open and close. The children gained early engineering understanding through examining how the symmetrical shells fit together, as well as learning about the mechanics of bivalves.

That afternoon in our classroom, we used technology to watch several videos to see how bivalves move. The children were curious to see how bivalves move around since they do not have legs like humans do. The videos helped the children visualize bivalve movement, which they were having a hard time imagining. After watching the videos we jumped like a cockle to get away from a sea star, we swam like a scallop by opening and closing our shell, and wiggled back and forth like a clam to bury ourselves in the sand. Reflecting on the lesson I realize the videos could have been used to begin the lesson so that the children had a better idea of how they move, before delving into the mechanics of bivalves.

That afternoon in our classroom, we used technology to watch several videos to see how bivalves move. The children were curious to see how bivalves move around since they do not have legs like humans do. The videos helped the children visualize bivalve movement, which they were having a hard time imagining. After watching the videos we jumped like a cockle to get away from a sea star, we swam like a scallop by opening and closing our shell, and wiggled back and forth like a clam to bury ourselves in the sand. Reflecting on the lesson I realize the videos could have been used to begin the lesson so that the children had a better idea of how they move, before delving into the mechanics of bivalves.

The students were exposed to concepts in multiple ways through art, hands-on objects, and kinesthetic learning, which made the concepts more concrete. They were playfully engaged with bivalves in different ways including exploring shells through touch, practicing fine motor skills, and using their bodies and imaginations. Through these playful techniques, bivalves came alive for the children.

We designed other playful experiences to teach the children about the biology of ocean animals. We explored how coral reefs are made by observing the physical attributes of live and preserved cora

l in the Sant Ocean Hall and a photograph of a coral reef in the museum’s Nature’s Best Photography Exhibit, by using our fine motor skills to build coral out of pipe cleaners, and by reading about how reefs are formed through the lifecycle of coral polyps. To end the lesson, the children used their bodies to create a coral reef. By engaging their bodies, the kids were up and moving (always a plus for young children), mimicking the various shapes of coral, and coming together to create a coral reef.

We also explored the physical characteristics of stingrays, specifically their flat bodies which mean that they cannot see what they eat. We pretended to eat like stingrays by feeling inside a mystery box and trying to detect what plastic food was inside. Through imagining what it might be like to be a stingray, the children continued to learn about the variety of body structures found in the oceans’ living organisms, and what these structures mean for the animals’ lives. After feeling a real sea star, and counting its legs, the children put cones on their feet, hands, and head to illustrate the five points.

We also explored the physical characteristics of stingrays, specifically their flat bodies which mean that they cannot see what they eat. We pretended to eat like stingrays by feeling inside a mystery box and trying to detect what plastic food was inside. Through imagining what it might be like to be a stingray, the children continued to learn about the variety of body structures found in the oceans’ living organisms, and what these structures mean for the animals’ lives. After feeling a real sea star, and counting its legs, the children put cones on their feet, hands, and head to illustrate the five points.

While the above examples were teacher-guided playful lessons, Tina and I also observed the children spontaneously exploring and communicating about the ocean life content through their child-directed play. For example, one child ran up to me on the playground and said, “Look, I made a whale, it has eyes and a tail!” I followed him to a spot on the playground where he had cleared fallen leaves to make a whale shape. After learning about octopus, one child grabbed a handful of stilts, and said, “Hey Tina, these suction cups are coming for you!” Another child found a torn ball on the playground, opened it up said, “Look, it’s a bulbous octopus head.” Even when playing with pretend food, the children found a way to use it for ocean play. The children attached pieces of yarn to the Velcro strip on plastic pears, and made them move like jellyfish. Playful lessons were essential in creating engaging experiences for the students to learn content about life in the ocean, but the children’s play also helped us to know what content they understood, and what they wanted to learn more about.

While the above examples were teacher-guided playful lessons, Tina and I also observed the children spontaneously exploring and communicating about the ocean life content through their child-directed play. For example, one child ran up to me on the playground and said, “Look, I made a whale, it has eyes and a tail!” I followed him to a spot on the playground where he had cleared fallen leaves to make a whale shape. After learning about octopus, one child grabbed a handful of stilts, and said, “Hey Tina, these suction cups are coming for you!” Another child found a torn ball on the playground, opened it up said, “Look, it’s a bulbous octopus head.” Even when playing with pretend food, the children found a way to use it for ocean play. The children attached pieces of yarn to the Velcro strip on plastic pears, and made them move like jellyfish. Playful lessons were essential in creating engaging experiences for the students to learn content about life in the ocean, but the children’s play also helped us to know what content they understood, and what they wanted to learn more about.

Through the playful and hands-on experiences in the museums and community, our class was able to learn about diverse animal life in the ocean. Handling objects helps make concepts more concrete and real, and playful approaches make content more engaging for children.

Please welcome guest blogger, Brooke Shoemaker, who brings her museum education expertise to The Early Years blog. Brooke was a pre-k classroom educator at the Smithsonian Early Enrichment Center (SEEC) in Washington, D.C. for four years, before joining SEEC’s outreach arm, the Center for Innovation in Early Learning as the Pre-K Museum Education Specialist.

Right to the Source: When Schools Fed the War Effort

By sstuckey

Posted on 2016-05-06

Exploring Science and History With the Library of Congress

After the United States entered World War I in April 1917, citizens could support the war effort by buying war bonds, conserving food on “Meatless Mondays” and “Wheatless Wednesdays,” and consuming less fuel at home and in their cars. Schools helped, too, as students planted vegetable gardens to increase the food supply.

After the United States entered World War I in April 1917, citizens could support the war effort by buying war bonds, conserving food on “Meatless Mondays” and “Wheatless Wednesdays,” and consuming less fuel at home and in their cars. Schools helped, too, as students planted vegetable gardens to increase the food supply.

School gardens, dating to the late 1800s, helped students get fresh air and exercise and learn about nature, which was especially important to city kids. Student gardeners learned about plants, soil, fertilizers, watering, and keeping records to help improve crop yield. They received valuable lessons in botany and entomology by learning the names, anatomy, and life cycles of garden plants and insects; detecting the role of earthworms in soil aeration; watching seed germination; observing pollination by bees and other insects; determining which insects ate which plants; and learning to recognize garden weeds.

During World War I, school gardens let students show their patriotism and support for troops fighting overseas. President Woodrow Wilson approved funding for the United States School Gardens program noting that school gardens were vital to the war effort. This 1919 poster (above) shows Uncle Sam leading an “army” of student gardeners.

School gardens were also important during World War II and have recently made a comeback as students learn more about the environment, where their food comes from, and the importance of wholesome food to good health.

About the Source

During World War I, posters encouraged citizens to modify their eating habits, plant victory gardens, and can fruits and vegetables so that more food could be sent for the war effort. The poster shown here is just one of many from World War I available online from the Library of Congress. To learn more about the school gardens movement, see these Library of Congress resource guides: School Gardens and School Gardening Activities, as well as a guide to related webcasts.

Related Student Explorations

- Botany

- Soil properties

- Gardening

- Nutrition

Danna C. Bell is an education resource specialist at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

Editor’s Note

This article was originally published in the April/May 2016 issue of The Science Teacher journal from the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA).

Get Involved With NSTA!

Join NSTA today and receive The Science Teacher, the peer-reviewed journal just for high school teachers; to write for the journal, see our Author Guidelines and Call for Papers; connect on the high school level science teaching list (members can sign up on the list server); or consider joining your peers at future NSTA conferences.

Join NSTA today and receive The Science Teacher, the peer-reviewed journal just for high school teachers; to write for the journal, see our Author Guidelines and Call for Papers; connect on the high school level science teaching list (members can sign up on the list server); or consider joining your peers at future NSTA conferences.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

5th Annual STEM Forum & Expo, hosted by NSTA

- Denver, Colorado: July 27–29

2017 Area Conferences

- Baltimore, Maryland: October 5–7

- Milwaukee, Wisconsin: November 9–11

- New Orleans, Louisiana: November 30–December 2

National Conferences

- Los Angeles, California: March 30–April 2, 2017

- Atlanta, Georgia: March 15–18, 2018

- St. Louis, Missouri: April 11–14, 2019

- Boston, Massachusetts: March 26–29, 2020

- Chicago, Illinois: April 8–11, 2021

Follow NSTA

The Power of Questioning: Guiding Student Investigations

By Guest Blogger

Posted on 2016-05-06

As authors of the popular NSTA Press book The Power of Questioning: Guiding Student Investigations, we get a lot of questions from readers. One of the top questions we get is, “How do we hold the learners accountable with questions?” Here is what we tell readers: The questions we choose chart the course of the discussion. Questions serve many purposes. Questions help students connect concepts, think critically, and explore logic and understanding at a deeper level. Questions can help teachers check for understanding. Questions can extend students’ thinking by requiring the students to justify their answers.

One emphasis of the Common Core English/Language Arts standards includes “asking and answering questions to demonstrate understanding” and “engaging effectively in a range of collaborative discussions.” Teachers may engage students in this type of discussion by asking justifying questions that hold the learner accountable for their learning. This type of question requires the student to provide evidence and support their ideas.

For example the teacher may ask the student, “Why do you think that?” or “What evidence supports your idea?” The way the teacher asks the question is very important. If the teacher asks questions with an inquisitive tone of wonder, the student will see that the teacher really wants to know what they are thinking and really wants to understand their logic and evidence. If the teacher asks the question with a sharp or critical tone, the question seems more like an interrogation. When teachers ask justifying questions with a constructive, inquisitive tone and intent a dynamic discussion is launched.

To learn more about ways to optimize questioning in your classroom, check out:

The Power of Questioning: Guiding Student Investigations

Julie V. McGough is a first-grade teacher/mentor at Valley Oak Elementary in Clovis, California; mrmagoojulie2@att.net.

Lisa M. Nyberg is a professor at California State University in Fresno, California; lnyberg@csufresno.edu; @docny

Click here for part one of The Power of Questioning blog series.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

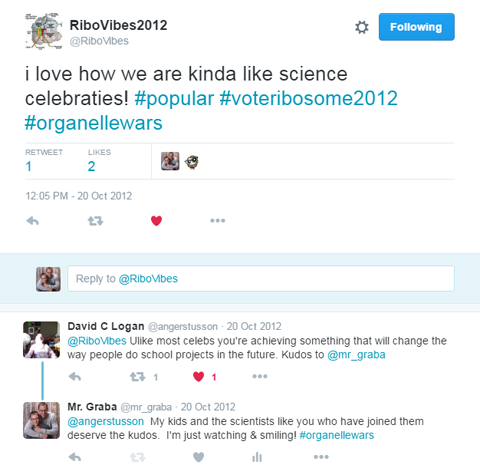

#OrganelleWars: A Model for Using Social Media in the Science Classroom

By Guest Blogger

Posted on 2016-05-05

Given the current political fervor over the candidacies of the people attempting to become our next president, now seemed like a good time to revisit one of the most successful projects I have had the good fortune of incorporating into my freshman biology classroom.

Launching a Model Organelle Campaign

In the fall of 2011, I had reached the point of the school year when it was time to start teaching my freshman biology students about the cell and its organelles. In my 14 years of teaching to that point, I had tried all types of different approaches to try and bring the cell alive for my students. I had tried direct instruction, having students build models of the cell, asking them to make analogies comparing the cell to a city, having them give presentations on individual organelles, even putting on a pretend radio show in class, and finally making fake Facebook pages on paper for each organelle. So as I prepared to begin the cell unit for the fourteenth time, I went to the Internet looking for inspiration (teachers are nothing if not good thieves, after all). One project I discovered came from Marna Chamberlain at Piedmont High School in California. The idea was to have students run an election campaign to get an organelle elected the most important organelle in the cell. The project involved promoting an organelle in class through the use of posters, brochures, and a speech. In addition to promoting their own organelle, students also had to smear at least five other organelles. This last requirement was designed, of course, to ensure that students researched the functions of other organelles in the cell as they worked on promoting their own. After a correspondence with Ms. Chamberlain, I decided to give the project a try.

Before getting started, I made one tweak to the project from its original incarnation, and that was to add a social media component to it. I had noticed, as most educators I work with had at that point, that students were often more preoccupied with their social media accounts than they were with their school work. My thought was that if I could bring school to where students were already spending a lot of their time, I might be able to capture their interest better than I had been able to in the past. The requirement for the social media component, which was optional for students to create, was that any account had to be a fake account in the name of the organelle. This was important in keeping the identities of my students anonymous and in keeping in line with the social media policy of my school district.

Moderate Success in Year One

The first year of the project went pretty well. My students made some great campaign posters and flyers, to the point that my classroom was covered in both promotional and smear posters. The social media component was fun, but the only people following any students’ accounts on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or Tumblr, were other students or myself. The proof of the effectiveness of this project, of course, would be in my students’ results on their end-of-unit assessment. I was concerned that although the project was fun, that perhaps they had not learned as much about cell organelles as in the past, since they had only been required to focus on six organelles. Students had been made aware that they were responsible for being able to identify and know the function of all of the organelles assigned in the project, but I was still nervous. In the end, however, students performed as well on the cell unit test in 2011 as they had in all my previous years, only this time they enjoyed and became engaged with the content. The project was successful enough that I decided to stick with it and try it again the following year.

Year Two: The Scientific Community Embraces the Concept

One of the keys to the project in 2012 was that it was a presidential election year, and it was the first campaign to truly use social media. My students were already naturally excited about the election process. The classroom was buzzing with activity, as students started creating campaign t-shirts, buttons, and stickers, in addition to the posters and brochures. They also created their Twitter accounts for their organelles, such as @GolgiBody2012 and @MightyMito42.

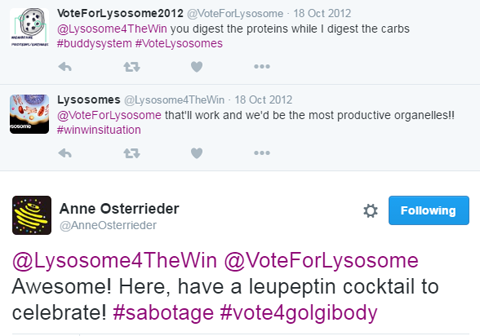

Then a funny thing happened. Someone I didn’t know started tweeting with my Golgi Body group. My first reaction was of course to determine who this person was, and I was initially quite nervous that a complete stranger had somehow found our little project on Twitter. But my apprehension turned to delight when the stranger turned out to be Dr. Anne Osterrieder (@AnneOsterrieder), a plant biologist who is an expert on the Golgi Body and a lecturer/researcher at Oxford Brookes University in England. Apparently Dr. Osterrieder had found one of my students’ Golgi Body Twitter accounts during a Twitter search for any relevant new tweets with content related to her organelle of interest.

From those initial tweets, the project exploded. A colleague of Dr. Osterrieder’s at Oxford Brookes University, Dr. John Runions (@JohnRunions), also began tweeting with my students. Dr. Runions gave our project the hashtag #organellewars on Twitter. Since then, that has become the name this project goes by in my classroom and online. Dr. Runions also has his own BBC radio show, where he goes by the alias Dr. Molecule, which he used to talk about my students and their project on one of his shows. Dr. David Logan (@angerstusson) from the Universite d’Angers in France, a plant biology researcher and self-described mitochondriac, also began tweeting with my students, helping to promote the mitochondria groups and smear the others. Soon other biologists from all over North America and Europe began tweeting with my students. The buzz the project created within the classroom and the school was incredible. My students were tweeting about organelles with scientists from Europe late at night on the weekend. In the past I had been lucky to get them to think about organelles at all other than when they were physically present in the classroom, but now they were actively engaged in learning about organelles beyond the four walls of my classroom, on a weekend, because they wanted to!

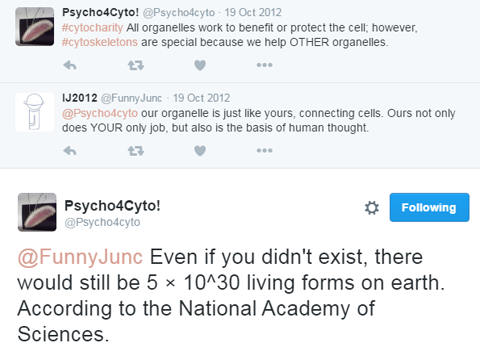

A Lesson in the Nature of Science

The results of the project the second time around went far deeper than I ever expected. Not only did my students learn about organelles, they learned far more important lessons about social media and science as well. The fact that this time around with the project there were experts on organelles interacting with my students, calling them out when they posted erroneous information, or asking them questions that inspired my students to d

ig deeper after they posted very superficial tweets regarding their organelle, gave my students an authentic audience. They were motivated to make sure that what they were posting was legitimate, appropriate, and able to be cited with reliable resources. I heard discussions among students about having been called out by a scientist online after having posted incorrect information about an organelle and needing to be careful about what they typed before hitting the “Tweet” button. Learning to have that filter before hitting “Tweet” or “Post” is an important skill for this generation to learn at a young age.

One point that I made very early on, after people from around the globe began interacting with us, was the far-reaching and very public nature of social media such as Twitter. Teenagers in general have a tough time grasping this concept. I think this is generally because the only people who interact with them online are typically their very limited social circle. That does not mean, however, that others outside of their small group of friends cannot see what their online activity looks like. It is especially important for the current generation of students to learn this lesson at an early age. College admissions counselors and future employers look at social media accounts to get a better understanding of the people they are admitting or hiring. Something that excites me is that these students now have a positive social media footprint to share with anyone who wants to start looking at their social media accounts.

Students See Scientists in a New Light

My students’ perceptions of scientists also changed from the stereotypes they brought with them into my classroom at the beginning of the year. Most students had the preconceived idea that scientists were boring old men in lab coats and goggles hidden away in a sterile lab all day long. By the end of the project, they were able to see that many scientists are actually vibrant, witty, young men and women who love science and their research, but also like doing the same kinds of things my students and everyone else enjoy.

I suspect that this coming year will be a fantastic time to attempt running this project. If this project sounds like something you might be interested in attempting some time in the future, I can be reached via email at bgraba@d211.org or @mr_graba on Twitter.

I suspect that this coming year will be a fantastic time to attempt running this project. If this project sounds like something you might be interested in attempting some time in the future, I can be reached via email at bgraba@d211.org or @mr_graba on Twitter.

Guest Blogger Brad Graba is an AP Biology Teacher at William Fremd High School in Palatine, Illinois.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

5th Annual STEM Forum & Expo, hosted by NSTA

- Denver, Colorado: July 27–29

2017 Area Conferences

- Baltimore, Maryland: October 5–7

- Milwaukee, Wisconsin: November 9–11

- New Orleans, Louisiana: November 30–December 2

National Conferences

- Los Angeles, California: March 30–April 2, 2017

- Atlanta, Georgia: March 15–18, 2018

- St. Louis, Missouri: April 11–14, 2019

- Boston, Massachusetts: March 26–29, 2020

- Chicago, Illinois: April 8–11, 2021

Follow NSTA

Given the current political fervor over the candidacies of the people attempting to become our next president, now seemed like a good time to revisit one of the most successful projects I have had the good fortune of incorporating into my freshman biology classroom.

Launching a Model Organelle Campaign