Help Your Students Achieve Earth Science Success

By Carole Hayward

Posted on 2015-04-20

NSTA Press authors Catherine Oates-Bockenstedt and Michael Oates, a daughter-father team, have collaborated on a second edition of Earth Science Success: 55 Tablet-Ready, Notebook-Based Lessons. The book provides a one-year curriculum with 55 classroom-proven lessons designed to follow the disciplinary core ideas for middle school Earth and space science from the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS).

NSTA Press authors Catherine Oates-Bockenstedt and Michael Oates, a daughter-father team, have collaborated on a second edition of Earth Science Success: 55 Tablet-Ready, Notebook-Based Lessons. The book provides a one-year curriculum with 55 classroom-proven lessons designed to follow the disciplinary core ideas for middle school Earth and space science from the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS).

Intended for teachers of grades 5-9, Earth Science Success emphasizes hands-on, sequential experiences through which students discover important science concepts lab by lab and develop critical-thinking skills. The first edition of the book focused more on the rationale for implementing the curriculum and the wisdom of using composition notebooks, this second edition focuses a special lens on the lessons themselves. The 55 lesson plans enable teachers to use electronic tablets, such as iPads, with best practice, field-tested methods.

Each of the labs is organized to follow a pattern of active involvement by students. Students are continually asked to search for evidence using a three-step discovery approach. The three steps are: anticipation, evidence collection, and analysis. Anticipation involves reflection on observations and a problem statement, recall of previous knowledge about the topic, discussion of misconceptions, and definition of concepts. Evidence collection includes hands-on laboratory investigation techniques. Analysis requires confirmation or rejection of results, reporting the findings, and drawing conclusions about the observations.

The book is organized into seven sections:

- Process of Science and Engineering Design

- Earth’s Place in the Solar System and the Universe

- Earth’s Surface Processes

- History of Planet Earth

- Earth’s Interior Systems

- Earth’s Weather

- Human Impacts on Earth Systems

The hope is that students will form good habits about testing and controlling all possible variables in their experiments whenever they are collecting evidence. They should be able to identify the manipulated, measured, and controlled variables in each experiment. Results should be reliable and valid. And students should set up controls, as a basis of comparison, so they can determine the actual charges in their data. This pattern of active involvement by students is followed throughout Earth Science Success.

The authors understand how busy a classroom science teacher is, and they know that successful strategies include those that save you time and promote skillful organization. Both composition notebooks and electronic tablets offer tremendous opportunities in this regard.

Why are notebooks, both electronic and nonelectronic, so valuable? One of the most important reasons is that students are able to organize, reflect upon, and achieve at higher levels. Students tend to have fewer missing assignments, and “no name” papers are a thing of the past. Tablets enable connections to internet research, word-processing capabilities, real-time data, and access to rich video vignettes to expand learning. The tablet and composition notebooks are also great resources to use at parent/teacher conferences.

This book is also available as an e-book.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

Providing Real-World Science Through CTE

By Debra Shapiro

Posted on 2015-04-19

As the need for skilled science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) workers grows, schools and districts nationwide are revamping or expanding their Career and Technical Education (CTE) STEM courses and curricula. “A lot of schools have been doing CTE for years, [but now] there’s a push for everyone to do it,” says Stephanie Haas, CTE teacher at CORE Butte Charter School in Chico, California. “In California, there’s a push for students to be both career-ready and college-ready…It’s more about the skills [employers need],” she contends.

While CORE Butte already offers CTE courses in STEM-related subjects like information technology and agriculture, “we are currently setting up a medical CTE pathway that will start next year…[W]e will be offering medical biology, medical anatomy [and] physiology, global health, special health projects (vaccinations), and health care career explorations. We plan on using HASPI (San Diego’s Health and Science Pipeline Initiative; www.haspi.org) medical science lab curriculum to help focus the application of our science courses on the medical/health field,” she relates.

“With the [nation’s] constantly growing and aging population, medical [staffing] needs are huge,” Haas asserts. “A lot of kids think the only medical careers are [as a] doctor or nurse, but there are other career paths they don’t know about, [such as] pharmacy technician or phlebotomist,” she points out. “We’ll [also] cover mental health, surgeries, [and other medical topics]…[Vaccination] is a hot topic now.

“Students will research the topics, then be exposed to the argumentation process,” she explains. “[Students will be asked] what discourse [they will] have. What will they say based on their research and the evidence? We’re already doing a lot of this in our classes; we’re just adding the career aspect in the pathway.”

At CORE Butte, “some CTE classes are like college classes…Some students are doing independent study,” Haas reports. “Students want to learn [the material] because it means something to them [career-wise]…It gives kids that buy-in.”

One challenge with CTE is that “career pathways don’t always fall in with No Child Left Behind and testing,” she observes. Fortunately, the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) and Common Core State Standards (CCSS) “offer more justification for career pathways,” she maintains. “CTE is a way to get to the NGSS.”

John Vreyens, science and CTE teacher at Chino Valley High School in Chino Valley, Arizona, agrees. “Our CTE standards are more like the NGSS standards than our state science standards. It’s more about performing a task than knowing a litany of facts. My CTE course (biotechnology) informs me on the way I really should be teaching my biology course.”

Giving Students More Choices

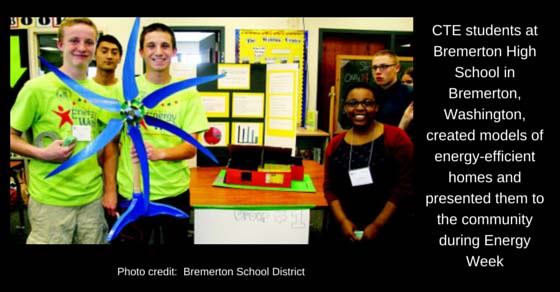

At Bremerton High School in Bremerton, Washington, “our ninth-grade science course is called STEM 9. We have it identified through our state as a CTE course, but our kids get science credit for it, rather than CTE credit. It meets all of the CTE requirements for leadership [and] employability, and [supports] NGSS and CCSS for [English language arts] and math,” says Emily Wise, one of Bremerton’s STEM 9 teachers.

“We encourage all ninth graders to take it,” and most do, notes Wise. “If students are enrolled in geometry [in ninth grade, instead of algebra], they can go directly into biology [as ninth graders], but they miss a year’s background in science.” STEM 9 also provides chemistry and physics background, which gives students an advantage. “They’ve had PBL (Project-Based Learning); [they] can delegate tasks and accomplish projects better than those who skip STEM 9…It helps a lot. I can see the difference in my chemistry students,” she relates.

“We’ve looked at the differences between CTE and traditional STEM courses a lot. We looked at 21st-century skills, rubrics, and requirements from the CTE department,” she recalls. For example, she and her colleagues considered “employability skills: How [could we] grade that? We do a lot of career exploration as well: What do people in STEM careers [actually] do?”

Wise believes “measuring students’ growth over time is easy with the [NGSS] science and engineering practices.” For example, teachers can consider “how good are [students] at tasks like writing a conclusion?”

“We also offer three other elective science/CTE courses for [grades 10–12]: Biotechnology, AP Environmental Science [APES], and Environmental Technology and Design. All of these classes can be taken as elective science or for CTE credits, depending on students’ credit needs and their post–high school pathway plans. This offers students flexibility in their science coursework, but also offers the 21st-century skills of a CTE class,” she contends.

“[The] CTE [designation] doesn’t necessarily mean the courses have no rigor. Our CTE classes are very rigorous,” asserts Briana Faxon, who teaches STEM 9 and APES at Bremerton. Her assertion is borne out in the description of the APES course: “AP Environmental Science is a rigorous and demanding course…In order to be successful, students should be highly motivated, a skilled reader, a critical thinker, and a problem solver.”

Most students who take APES “have earned their science credits already…[This year, only] five out of 25 students are taking [APES] for CTE credit,” she reports. “I get valedictorians in my class, along with [students headed for] community college and potential dropouts…It’s sometimes frustrating, and sometimes rewarding. They learn from one another, and learn we all have to work together. It feels like it levels the playing field in a good way.”

“We try to pull in so many different projects so [the courses] can appeal to [a wide range of students’] interests,” says Faxon. “We’re constantly changing our projects. We have the flexibility to do that,” she explains. When the teachers need help, “we have an advisory board for our STEM CTE courses that includes science and engineering professionals. They provide their expertise to us.”

And though students take the AP test in May, APES continues through June, so Faxon has time to assign a career research project. The project helps because in college, “if they change majors, they are familiar with other careers in science fields,” she contends.

“Our district CTE director is also our district science director, and she has been instrumental in bringing these courses to our high school, and has been very supportive of our science teachers as we work to integrate science and CTE in order to better prepare our students for college and careers. The work has been challenging, and we are far from done, but I really enjoy being able to promote both our science program and our CTE courses because I firmly believe in them,” Wise maintains.

“Emily and I [tell students], ‘Here are the college skills you need.’ [We want the] doors to be open to any career students want to pursue, and that they’ll have the skills they need,” Faxon asserts.

Integrating Science in CTE Courses

Ed Engelman teaches integrated science in seven of 12 CTE courses offered by the Delaware-Chenango-Madison-Otsego Board of Cooperative Educational Services (DCMO BOCES) in New York. He co-teaches with the CTE instructors of such courses as Auto Technology, Security and Law Enforcement, and Carpentry and Building Construction. “Eight school districts send juniors and seniors [to DCMO BOCES] for half a day…This [arrangement] is very different from the self-contained technical high school model,” he explains, and the courses are “quite different from the courses taught in [students’] home schools.”

Every five years, the courses “go through the recertification process. We map the curriculum and show that the students are receiving 108 hours of science over two years,” he reports. “Credits are awarded by the sending districts,” he adds.

The number of CTE courses has grown somewhat in recent years because “students are looking for meaningful experiences. There are many students who learn better by doing, especially kinesthetic learners. [CTE] appeals to those students,” he contends.

“Many CTE students feel [traditional] courses and testing aren’t real. Repairing a car or creating graphic arts posters is real work; it produces a real product,” he observes. In the Visual Communications and Graphic Design course, for example, students photograph macroinvertebrates and create identification cards for them that will be used by various organizations. “Even though some of the students don’t like insects, they know the cards will be used,” he maintains.

Second-year students are exposed to a real-world work setting by a short-term placement or job shadowing experience. Engelman believes many students would not graduate without CTE courses because they “act as a motivator like sports does. [The students] do well in school because they like the hands-on experience.”

In addition, CTE can be “a place for kids with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) to succeed” because in CTE courses, “they’re moving about, and more active.”

Most of the students ultimately enroll in college because a high school diploma is no longer sufficient for many careers, Engelman points out. For example, automobiles “are much more complex than they used to be. Everything is just so much more wired,” he remarks.

“The more motivated, or those who want better-paying jobs, go to two- or four-year schools afterward,” he reports. He believes the CTE students have an advantage over their more traditional peers because they “have a better idea of what they’re getting into, a better all-around feel for it” as a result of their hands-on experiences.

This article originally appeared in the April 2015 issue of NSTA Reports, the member newspaper of the National Science Teachers Association. Each month, NSTA members receive NSTA Reports featuring news on science education, the association, and more. Not a member? Learn how NSTA can help you become the best science teacher you can be.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

Senate Education Committee Passes ESEA Reauthorization Bill

By Jodi Peterson

Posted on 2015-04-17

On Thursday April 16, 2015, on a unanimous vote of 22-0, the Senate HELP Committee approved a bipartisan bill that rewrites the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (No Child Left Behind). This means the bill will go to the Senate floor for final consideration, although floor time has not yet been scheduled.

On Thursday April 16, 2015, on a unanimous vote of 22-0, the Senate HELP Committee approved a bipartisan bill that rewrites the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (No Child Left Behind). This means the bill will go to the Senate floor for final consideration, although floor time has not yet been scheduled.

During Senate markup of the bill, known as the Every Child Achieves Act, 60 amendments were debated, 21 amendments offered and withdrawn, 29 amendments were passed, and 8 amendments failed. See the list of amendments here. Most of the amendments were adopted via voice vote with little controversy or withdrawn out of respect for maintaining the bipartisan nature of the legislation.

I’m pleased to note that the Franken-Kirk-Murray STEM amendment, which restores STEM programs to the federal education bill, was adopted by a vote of 12-10 during consideration of the bill. The amendment language stipulates that each state receive formula-based funding to support partnerships between local schools, businesses, universities, and non-profit organizations to improve student learning in the critical STEM subjects. Each state would choose how to spend and prioritize these funds, which can support a wide range of STEM activities from in-depth teacher training, to engineering design competitions, to improving the diversity of the STEM workforce. This is a huge win for the STEM education community. See More Details on Franken-Kirk-Murray STEM Funding Amendment.

NSTA was very active in advocating for this amendment. We also spearheaded a letter with the STEM Coalition to Senate HELP Committee leaders urging support for STEM education as an ESEA priority. The letter was signed by a diverse array of more than 90 local, state, and national organizations that includes teacher and education groups, and professional and civic societies, and major corporations. Read the letter here.

Three amendments also to note, now part of the bill: An amendment from Sen. Richard Burr, R-N.C. would alter the Title II funding formula so that it’s based 80 percent on poverty and 20 percent on population.

An amendment by Sen. Tammy Baldwin, D-Wis., would allow states to use federal funds to audit the number and quality of tests and eliminate any they deem ineffective or of low-quality. The same provision was adopted in the House ESEA bill.

There were also a number of amendments relating to Title I portability introduced then withdrawn, that would allow funding for low-income students to follow those students to the public or private school of their choice. It is expected that these amendments, and amendments to strengthen the accountability system, will be offered during floor debate in the Senate.

My April 10 blog post outlines most of what is in the Every Child Achieves Act and you can read more about the mark up in this Education Week blog. Hill staffers are now incorporating amendment language into the bill, and we will bring you the final product when it is released and news on when/if this bill will reach the Senate floor.

Stay tuned and look for upcoming issues of NSTA Express for the latest information on developments in Washington, DC.

Jodi Peterson is Assistant Executive Director of Legislative Affairs for the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) and Chair of the STEM Education Coalition. e-mail Jodi at jpeterson@nsta.org; follow her on Twitter at @stemedadvocate.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

On Thursday April 16, 2015, on a unanimous vote of 22-0, the Senate HELP Committee approved a bipartisan bill that rewrites the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (No Child Left Behind).

On Thursday April 16, 2015, on a unanimous vote of 22-0, the Senate HELP Committee approved a bipartisan bill that rewrites the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (No Child Left Behind).

Science and the Media

By David Evans, NSTA Executive Director

Posted on 2015-04-17

Scientists Christian Tomasetti and Bert Vogelstein published an article in the journal Science, “Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions” (Science, January 2, 2015, p 78). The discussion this article engendered provides an excellent teaching tool for teachers to showcase how scientific debate takes place among members of the scientific community with the goal to elevate the quality of a body of knowledge and how it is different from the way the popular press reports on and communicates this work.

The amount and range of news coverage this research article received was remarkable. Most of the popular press, unfortunately, reported a simplified version of the story citing the statement that two-thirds of cancers are caused by chance and not by genetic or environmental factors without noting that that the authors explicitly stated that a number of the most commonly occurring cancers were not included in their study. Few of the news accounts reported that the original article addressed variation in cancer risk but not absolute cancer risk, therefore misleading readers that most cancers are due to ‘bad luck.’ The Guardian ran a story, “Bad luck, bad journalism and cancer rates,” that tried to clarify the science for the popular media and provided a simple account of the actual work while chastising colleagues in the news business.

In contrast to often poorly reasoned discussion in the popular press, members of the science community weighed in with criticism as well. Authors of six letters in the journal Science raised a number of mathematical and procedural questions about the work. Many of them were also as concerned with how people would interpret the results as they were with identifying errors. For example, the letter by Ashford, et al., begins “The report […] is dangerously misleading….” And in a subsequent blog post, one of the authors writes, “Our letter to the editor of Science not only challenges the misstatements of the reports that most cancers are due to ‘bad luck’, but points out that such misstatements dangerously undermine successful efforts to prevent cancers.”

In their response to the letters, Tomasetti and Vogelstein address each of the technical points either directly or by referring to the Supplementary Materials published online by Science. They also offer their views on the non-scientific aspects of the criticism. I encourage you to read the letters as well as the response.

The communications surrounding this very interesting and possibly important scientific paper can make for a very rich discussion about the differences between rhetorical argument that can be found in the mainstream press and blogosphere and the evidence-based argument included in the letters and response. It’s vital that we help our students understand the difference between the two.

Dr. David L. Evans is the Executive Director of the National Science Teachers Association. Reach him at devans@nsta.org or via Twitter @devans_NSTA.

Dr. David L. Evans is the Executive Director of the National Science Teachers Association. Reach him at devans@nsta.org or via Twitter @devans_NSTA.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

Learn How to Reimagine Your Science Department

By Carole Hayward

Posted on 2015-04-16

In NSTA Press’ new book, Reimagining the Science Department, authors Wayne Melville, Doug Jones, and Todd Campbell pose some atypical questions:

In NSTA Press’ new book, Reimagining the Science Department, authors Wayne Melville, Doug Jones, and Todd Campbell pose some atypical questions:

“Departments are a ubiquitous feature of secondary schools; but where did they come from, what purposes do they serve, and what is the traditional role of the chair?”

The authors explain that it is necessary to ask these questions if you want to understand the importance of both the department and the chair in the teaching and learning of science. By knowing how the features in contemporary departments have evolved, you can begin to appreciate the power of departments in perpetuating a particular view of science education. If you understand this history, then as a chair (or aspiring chair), you will have a knowledge base from which to work in reforming science instruction in your department.

Departments are not just convenient administrative structures within secondary schools, although that is often how they appear. Contemporary science departments are simultaneously learning communities, which powerfully influence what and how teachers teach and administrative organizations within secondary schools. A chair that sees the department as both organization and community is in the best position to judge the most appropriate approach to the issues being faced.

Implementing and supporting the teaching and learning rooted in engaging students in science and engineering practices to use disciplinary core ideas and crosscutting concepts to explain phenomena or solve problems outlined in the NGSS will require changes in teachers’ professional learning—changes that are intimately linked to the roles and responsibilities of the department chair.

To encourage teachers to take greater ownership of the reforms will, to a large extent, depend on your leadership capabilities. These capabilities, and increasingly those of individual teachers, will impact and ultimately shape what the department looks like in the future.

Departments do not, however, work in isolation from the rest of the school. To reimagine the department is to also be active in developing strong political and practical relationships with school administrators. Without their support, change is difficult to initiate and even more difficult to sustain. The aim of reimagining the department is to develop a long-term culture that is simultaneously owned by the teachers and supported by school administrators.

Building trust within the department is paramount. Faith in your colleagues and the assumptions that reimagining the department are based on emanates from trust. Leading a paradigm shift in thinking and practice of any magnitude is a challenge that requires leadership based on hope, trust, faith, and civility from both the chair and the department, supported by school administrators.

Reimagining the Science Department will help you understand the importance of the position and develop your ability to lead. School administrators or school board members will find it deepens the commitment to developing a department in which the practices of science are taught for the benefit of all students. The authors divide the book into five key sections:

- A History of the Science Department

- Changing Scripts

- Roles and Responsibilities

- Getting Started

- Building for the Long Term

This book is also available as an e-book.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

In NSTA Press’ new book, Reimagining the Science Department, authors Wayne Melville,

In NSTA Press’ new book, Reimagining the Science Department, authors Wayne Melville,

Fun and Science with the Weatherhawk myMET digital Windmeter

By Martin Horejsi

Posted on 2015-04-15

Checking the windspeed on the Slickrock trail in Moab, Utah. The air was moving at a steady 18 miles per hour. Just enough to make you a little nervous when bicycling along cliff edges. As you can see in the picture the neck lanyard is being pushed away by the wind. Until another indicator was added, the lanyard was used to position the meter correctly for accurate readings.

The Weatherhawk myMET Windmeter

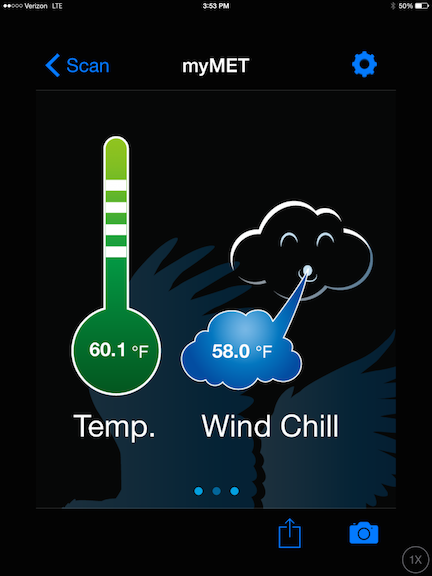

Measuring wind speed is just one of the many facets of exploring climate science. Wind, or the natural noticeable movement of air is created and changed by many well-known factors including temperature, barometric pressure, landscape, and time of day among others.

The use of a digital anemometer allows students to put a quantity on wind speed and a compass will provide direction. Add temperature and you can calculate wind chill. Note the time of day and you can create a detailed date picture of local air movement.

Popular anemometers are often cups or propellers. The myMET uses an eight-blade propeller about an inch (2.54cm) in diameter. The meter and electronics reside an retractable plastic housing that uses a thumb-slider on the right side. A tripod mount is on the base. The meter runs on two CR2032 button batteries contained in a reverse-threaded (turn right to loosen) O-ring sealed comparment.

The Weatherhawk myMET is a powerful solution to measuring windspeed and temperature as both a standalone device, and in tandem with a tablet such as the iPad. Alone the myMET wind meter provides wind speed, air temperature, and wind chill. But paired via Bluetooth to a comparable iOS or Android device, the meter’s measurements are recorded on one of three screens as well as a data overlay on a photograph taken by the tablet’s camera. myMET outputs the wind speed in miles per hour or meters per second, and temperature in Fahrenheit or Celsius. Here are some examples:

Average and Maximum wind speed along with a compass using the onboard tablet sensor so there must be alignment between the myMET meter and the tablet.

To assist in keeping the myMET perpendicular to the wind direction Weatherhawk offers a tripod-mounted weather vane attachment that holds the myMET. For my tests, I used the included lanyard to position the meter, but later added a length of yarn since the meter could be dropped if the neck strap is not used for its intended purpose.

Below are some images where the myMET wind speed meter was tested along with some lessons learned along the way.

In this image, the windspeed is gusting 33 miles an hour. In the background is a semi truck and trailer that blew over on the interstate highway when the gusts were a little higher just minutes earlier.

Here is a closeup of accident. It must have been some gust since this northbound truck was mirrored by a complementary southbound truck that also blew over just a few hundred meters away.

Here is a link to the local news outlet mentioning that there were no serious injuries of anyone involved.

Balanced Rock in Arches National Park is a shocking artifact of erosion. The massive boulder is constantly buffeted by wind on the high desert plain. Using the iPad camera and myMET meter, the image documents both the place and the windspeed.

Wind farms are cropping up where wind is both steady and directionally consistent. High speed wind or heavy gusts are not ideal. In the photo a steady 8 mph wind is spinning the massive turbines just fine. Also, you can see the yarn added to the meter to help keep the meter perpendicular to the wind direction.

With the increased emphasis on green energy especially wind power, being able to collect accurate numbers for air movement both over time and maximum speed the beginning of some great science and discussion. Hearing or reading a wind speed value is a daily occurrence, but understanding what the numbers feel like takes first-hand experience.

This chart shows the miles per hour of wind compared to physical indicators.

|

Speed (mph) |

Designation |

Description |

|

1-3 |

light air |

smoke drift indicates wind direction |

|

4-7 |

light breeze |

weather vane moves, leaves rustle |

|

8-12 |

gentle breeze |

leaves and twigs in constant motion |

|

13-18 |

moderate breeze |

dust and loose paper raised, small branches move |

|

19-24 |

fresh breeze |

small trees sway |

|

25-31 |

strong breeze |

large branches move, wind whistles wires |

|

32-38 |

moderate gale |

whole trees move, walking affected |

|

39-46 |

fresh gale |

twigs break off trees, walking difficult |

|

47-54 |

strong gale |

slight structural damage occurs, branches break |

|

55-63 |

whole gale |

trees uprooted, considerable structural damage |

|

64-74 |

storm |

widespread damage |

|

75+ |

hurricane |

severe and extensive damage |

While Weatherhawk does offer a padded case for the myMET, I opted for a ridged case that could take rough student handeling. The myMET seems quite durable on its own and the retracting case that protects the moving parts is probably plenty for most uses. Their padded case is a notch above that. And my Outdoor Products hard case (for sunglasses) is yet another notch higher.

Once back in the classroom, I wondered about using the meter to answer a question I’ve had for a while. What is the windspeed of various sizes and types of fans at different distances. The results will blow you away. Here’s a chart from the KidWind Project to get you started.

STEM Today for a Better Tomorrow: Coming to You, Virtually, April 25

By Lauren Jonas, NSTA Assistant Executive Director

Posted on 2015-04-14

The next NSTA virtual conference (STEM Today For a Better Tomorrow) is happening Saturday, April 25, 2015, 10 a.m. – 6 p.m. ET. Participants will follow one of three strands (Elementary, Secondary, or Administrator)—or mix and match sessions if they prefer—and do the following:

- Learn from STEM educators who are implementing STEM programs and activities

- Meet and network with other teachers and administrators interested in STEM

- Learn about post-conference, STEM-related opportunities available via NSTA

Leaders to Learn From

What’s the best thing about this virtual STEM conference? The people, of course! Meet a few of the presenters, and get a sense of why this unique online learning environment is the perfect way to understand the role that STEM education plays for students interested in pursuing STEM careers.

Barrington Irving became the youngest person to fly solo around the globe. On his 97-day journey, he flew 30,000 miles in a single-engine plane called Inspiration. Irving’s educational initiative, the Flying Classroom (launched in 2014 from Washington, D.C.), will embark on two more rounds of Flying Classroom expeditions in the U.S. and abroad in September 2015 and 2016.

Barrington Irving became the youngest person to fly solo around the globe. On his 97-day journey, he flew 30,000 miles in a single-engine plane called Inspiration. Irving’s educational initiative, the Flying Classroom (launched in 2014 from Washington, D.C.), will embark on two more rounds of Flying Classroom expeditions in the U.S. and abroad in September 2015 and 2016.

“Can’t wait to share my story of how STEM changed my life when I thought football was everything. From the football field, I now explore the world as a record-setting pilot and continually discover amazing careers within STEM.”

Laura Mackay is a science coach and magnet liaison at an elementary STEM magnet program at Ed White Elementary in El Lago, Texas.

Laura Mackay is a science coach and magnet liaison at an elementary STEM magnet program at Ed White Elementary in El Lago, Texas.

“Creating a new STEM program at a school is a difficult process; there is so much information, it’s hard to know where to start! I know I was overwhelmed trying to figure out how to build capacity in teachers to create a new STEM program. Even though I had helped design a gifted magnet school and a two-way immersion magnet program, STEM seemed very different. But I learned that the process of building capacity in teachers to change a school is basically the same. So, now I look forward to sharing an easy way for administrators to structure a process that allows teachers to build a program that best suits their students’ needs. The goal is to get others involved in learning and creating so that the workload is shared. This process works with building any type of new initiative in a school, not just a STEM program.”

Brenda Wojnowski is CEO and president of WAI Education Solutions, an education-focused consulting firm geared toward non-profit, school system and university clients.

Brenda Wojnowski is CEO and president of WAI Education Solutions, an education-focused consulting firm geared toward non-profit, school system and university clients.

“The webinar Celeste Pea and I are presenting highlights professional development models and approaches used by several states and districts to significantly improve teaching and learning in one or more areas of STEM education. The goal for each model or approach is to develop teachers’ and students’ knowledge and skills, and, ultimately, to improve student achievement in STEM education.We are excited to share this information and hope many educators will find it useful.”

Eric Brunsell is an assistant professor in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction and the Excel Center at the University of Wisconsin – Oshkosh.

Eric Brunsell is an assistant professor in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction and the Excel Center at the University of Wisconsin – Oshkosh.

“I am excited for the STEM Virtual Conference for many reasons. Interest in STEM education is high, but often these discussions are isolated or result in new programs or courses. If we really want to have a positive impact on students’ understanding of STEM disciplines and careers, the efforts need to be made in our core academic areas. So, what does STEM mean in a traditional middle or high school science classroom? I will share some structures and examples during my session. I also hope that there is a rich and active discussion.”

Jim O’Leary is the Maryland Science Center’s lead space science and astronomy specialist and has hosted a radio program for 12 years on the local NPR affiliate, examining the latest developments in space science and astronomy.

Jim O’Leary is the Maryland Science Center’s lead space science and astronomy specialist and has hosted a radio program for 12 years on the local NPR affiliate, examining the latest developments in space science and astronomy.

“I’m really looking forward to sharing the great images of the Hubble Space Telescope and the science behind them. Hubble is coming up on 25 years in space and has taken thousands of spectacular images and taught us new things about the universe. I know these images can inspire students to wonder about the cosmos and even pursue STEM careers. And being in Baltimore, we’re thrilled to be the home of the Space Telescope Science Institute, where all of Hubble’s science takes place.”

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2015 STEM Forum & Expo

2015 Area Conferences

One Last Look at #NSTA15 Chicago

To see more from the 2015 National Conference on Science Education in Chicago, March 12-15, please view the #NSTA15 Facebook Album—and if you see yourself, please tag yourself!

Follow NSTA

Science and Literacy: Reflections on Time

By David Evans, NSTA Executive Director

Posted on 2015-04-13

Science and literacy are inherently linked in so many ways. Just as a matter of practice, scientists must possess great proficiency in reading dense, data-filled texts. They must be expert technical writers who can describe their proposed studies for funding considerations, detail their experimental protocols for their peers to replicate, and summarize their work for general audiences. More crucial to furthering the study of science, they must be confident in their abilities to argue from evidence, both orally and on paper, or, in the parlance of the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), they must be able to “obtain, evaluate, and communicate information” and “engage in argument from evidence.”

For some time the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) has recognized similarities in the ways in which both reading and science are taught and has advocated the powerful reciprocal value of linking science and literacy in the classroom. As reported in Science for English Language Learners, “science and language become interdependent, in part because each is based on processes and skills that are mirrored in the other. These reciprocal skills give teachers and students a unique leverage: by merging science and language in the classroom, teachers can help students learn both more effectively.” This conclusion was drawn while studying the integration of learning English as a second language and the learning of science (see also Teaching Science to English Language Learners). However, the mutually beneficial outcomes have held true with native speakers as well. Using literacy teaching strategies during science instruction “not only provided teachers with tools for guiding students’ interactions with texts and with physical inquiry, but also motivated students to engage with the texts and provided a window into student thinking” (Linking Science and Literacy).

Equally compelling is the research supporting the use of science to pique the interests of reluctant readers, particularly with regard to nonfiction texts. As the authors of Inquiring Scientists, Inquiring Readers assert, “Scientific inquiry provides an authentic context for reading, writing, and dialogue. Having a compelling reason to read a book, record observations, and communicate with others increases students’ motivation to engage in nonfiction reading.”

Perhaps most noteworthy for time-strapped teachers, science is the perfect vehicle for imparting not just science knowledge but also reading and even math. The tremendous popularity of our Picture-Perfect Science program, “Teaching Through Trade Books” column, and annual list of Outstanding Science Trade Books are testament to that!

As educators, we are cognizant of the deep connections between science and literacy. However, we need to draw those connections for our students. We need to help them appreciate the ways in which language and scientific literacy open up the world to them. Literature and science—and for that matter, philosophy and the arts—offer different vantage points from which to tackle some of the same phenomena.

Take, for example, an enduring challenge for physicists, a problem known as “times’ arrow,” the fact that “all the equations that best describe our universe work perfectly if time flows forward or backward.”(Alan Alda launched a competition that encouraged middle school students to explore this very question and required them to communicate their scientific ideas in a clear and engaging manner.) A contemporary summary is in a recent Scientific American article. As I read the essay, I recalled the opening lines from T.S. Eliot’s “Burnt Norton”:

Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future

And time future contained in time past.

Eliot wrestles with time as an abstract concept, exploring our perceptions and their implications with subtlety and nuanced diction instead of as equations. Still, he uses literature as a mechanism for approaching an everyday phenomenon, time, in much the same way a scientist uses an equation or model to describe the world. Neither the poet nor the physicist can offer a definitive answer, but their perspectives are equally valuable as catalysts for deeper thought.

In other words, the connection between science and literacy can be simple, elegant, two different approaches to marveling over the same phenomenon. Reading, writing, and science (not to mention math, social studies, music, and art) play equally important roles in preparing our students to be thoughtful and responsible world citizens. Our parsing of knowledge into subjects typically demands that we teach these subjects as disparate lessons, but provides even more reason to help students make those important connections, such as that between literacy and science. After all, what is science but a tantalizing story of discovery and prediction that unfolds as generations of thinkers encounter phenomenon, seek explanations, and communicate their findings?

David Evans is Executive Director of the National Science Teachers Association

David Evans is Executive Director of the National Science Teachers Association

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

Webinar Wednesday for the Week of the Young Child, April 12-18

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2015-04-12

Are you celebrating the Week of the Young Child (WOYC)? Music Monday, Tasty Tuesday, Work Together Wednesday, Artsy Thursday and Family Friday are the daily themes set by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) to inspire us to “focus public attention on the needs of young children and their families and to recognize the early childhood programs and services that meet those needs.” NAEYC offers resources for meeting the needs of the children in our care.

Are you celebrating the Week of the Young Child (WOYC)? Music Monday, Tasty Tuesday, Work Together Wednesday, Artsy Thursday and Family Friday are the daily themes set by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) to inspire us to “focus public attention on the needs of young children and their families and to recognize the early childhood programs and services that meet those needs.” NAEYC offers resources for meeting the needs of the children in our care.

On Wednesday I will be “working together” with you and others by attending a web seminar to build my understanding of the Early Childhood Science Education position statement, written and adopted by the National Science Teachers Association and endorsed by NAEYC.

“STEM Starts Early: Guidance and support from the NSTA Early Childhood Science Education Position Statement,” will take us through the position statement, and its key research-based principles that inform and guide science teaching and learning in the early years. I’m looking forward to hearing the stories from real classrooms and viewing short classroom videos for analysis and discussion. We will have the opportunity to consider the position statement’s recommendations for:

“STEM Starts Early: Guidance and support from the NSTA Early Childhood Science Education Position Statement,” will take us through the position statement, and its key research-based principles that inform and guide science teaching and learning in the early years. I’m looking forward to hearing the stories from real classrooms and viewing short classroom videos for analysis and discussion. We will have the opportunity to consider the position statement’s recommendations for:

- Teaching—creating an environment and facilitating explorations that support children’s collaborative inquiry in physical, life, and earth science

- Professional development—providing experiences for teachers and education providers that really build their capacity to promote young children’s science learning and inquiry

- Policy—committing resources to support early childhood science education

Register on the NSTA Learning Center site: http://learningcenter.nsta.org/products/SeminarRegistration.aspx

Thank you to the GE Foundation for underwriting this resource!

Thank you to the GE Foundation for underwriting this resource!

See you online on Wednesday, April 15, 2015 at 6:30 p.m. ET / 5:30 p.m. CT / 4:30 p.m. MT / 3:30 p.m. PT

Are you celebrating the Week of the Young Child (WOYC)? Music Monday, Tasty Tuesday, Work Together Wednesday, Artsy Thursday and Family Friday are the daily themes set by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) to inspire us to “focus publi

Are you celebrating the Week of the Young Child (WOYC)? Music Monday, Tasty Tuesday, Work Together Wednesday, Artsy Thursday and Family Friday are the daily themes set by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) to inspire us to “focus publi

Connected Learning at #NSTA15: Emerging Contexts for Deeper Engagement

By Guest Blogger

Posted on 2015-04-10

Featured speaker Sam Dyson invited attendees to join his personal hive in Chicago last month at NSTA’s National Conference on Science Education. Sponsored by the Shell Corporation, Dyson focused on connected learning and emerging contexts for deeper engagement. Set against the backdrop of a three-act play, Dyson modeled the importance of “connectedness” with a community of learners. Dyson’s first teaching experiences transpired in Johannesburg, Africa, where he admitted he did not know much about teaching, but picked up a few things while teaching in Chicago. Working now for the Mozilla Foundation in youth programming, Dyson brought a well-rounded perspective to his session; I was immediately engaged.

From “Oh No” to “Aha”

In Act I, Dyson revealed his first “Aha” moment in teaching, which interestingly came through his first “important failure.” He was facilitating a classroom demonstration about momentum, mass, and inelastic collisions. In the demonstration, the carts “stick together” when they collide as the approaching car overtakes the slower lead cart. Dyson thought his students had an adequate background to predict the outcome (that the carts moving along the same path would collide and stick together as they continued down the track). To Sam’s surprise, as the demonstration unfolded, one of his students refused to believe what he physically observed. Why? Because the student had no background knowledge, reference point, or tangible observations of this phenomenon occurring in his everyday life. Sam eloquently described this as a failed demonstration, but also as the one that created his “aha” moment. For the first time, he saw and understood deeply that the internal thinking and experiences that students bring to the learning environment undergirds future understanding. This discrepant event did not match the student’s sense making of his world. Dyson realized that teaching was not about what we know, but what we believe.

I wonder how many of us also think about our first “aha” moments early in our careers. Sam’s insight early into his career resonated with me, and I suspect many of you, too! We know that a student is not a tabula rasa, or blank slate, onto which we dump knowledge. As demonstrated by research in cognitive learning sciences about how people learn, we live in a dynamic world with rich interactions of science phenomena and engineering design solutions. We seek to make sense of these observations and form personal working theories and reasons for how these things occur in nature or are made by humankind. We form many of these known preconceptions internally, as part of our own “sense-making,” and as research shows, these preconceptions are deeply seated, resistant to change, and hard to overturn. But fear not, there are also research-based strategies to help learners challenge their own internal logic, face it head on, test it, wrestle with it, and see if it holds up! NSTA has several publications that may assist you across the K–12 spectrum. For example, author Page Keeley’s Uncovering Student’s Ideas in Science series draws upon this research and provides formative assessment questions (or probes) to make this internal student thinking visible. Working with teachers and classrooms, she has developed probes for elementary science, as well as physical, life, and Earth/space science. Page also partnered with Richard Konicek-Moran in an upcoming book titled Teaching for Conceptual Understanding in Science (coming off the NSTA Press any day now) that brings field-tested strategies teachers can use immediately in the classroom to empower students’ learning.

Dyson learned early on that Aha moments are not necessarily when we figure out a solution, but when we gain insight into the problems with which students are wrestling. In his presentation, he stressed that such insight is necessary to provide the kind of learning experiences that really allow students to “connect” new information to what they already believe, and that it is important to understand the difference between knowing and understanding. So, while we continually acquire new information from the world around us (knowing), it is critical for students to be able to apply this knowledge in situ, acquiring a deeper understanding (for instance through challenging “discrepant events”). Students progress until they cannot continue with their internal “sense-making” theories and are forced to reshape and change their understanding, thus allowing them to grow again, pushing through these conceptual “sense-making” barriers. Dyson’s ideas for the arc of student understanding reveal an initial upward arc, but then a “trough” as deeper learning becomes more challenging, a larger investment of time, and a commitment is needed to reach the higher deeper learning arc. Dyson contrasted this against the notion of “superficial learning,” which some might equate to mere recall and recognition of facts versus deeper more flexible learning where understanding is applied across multiple areas, such as the cross-cutting concepts espoused in three-dimensional teaching and learning in K–12 Framework for Science Education and the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), concepts such as patterns, cause and effect, systems and systems models, and stability and change to name a few. Indeed what Dyson shared reflects the work of the National Academies and the NGSS, which stresses that deeper learning of the disciplinary core ideas in science occurs as students engage in authentic science and engineering practices, while recognizing cross-cutting concepts like those above. As I was focused on what Sam was sharing, I scanned the room, seeing a sea of heads nod in affirmation. Check out the NSTA NGSS Hub for tools, resources and learning opportunities around the NGSS.

Connected Learning Equals Flexible Learning!

For Act 2, Dyson asked small groups to discuss what they thought the term Connected Learning meant. Interestingly, I informally asked session attendees this question before Sam started his talk, given it was in the title. I asked why attendees selected this session; what did they want to get from the session? The answers might surprise you! Some acknowledged that Shell-sponsored presentations were always informative and came knowing that, by reputation, the talk would be engaging and worthwhile. Others cited the importance of multicultural diversity in our featured sessions and appreciated the diversity of opinion and expertise represented by the selected speaker. Interestingly, several conflated the notion of “connected learning” with the US Department of Education project called “Connected Educators” and had come wanting to learn how to build successful online communities. Many, though, understood the emphasis of the talk on discussing a pedagogical point of view stressing the importance on connecting students’ local environment and the world in which they live to the science concepts we are presenting to help them better understanding the world in which they live. To make connections and be critical thinkers, challenging their internal views and the importance of teachers on structuring these types of experiences.

Dyson shared what many agree with, the importance of a constructivist learning cycle for teaching, and referenced the 5E model developed by BSCS, where students cycle through (not necessarily linearly or within a single period) engagement, exploration, explanation, elaboration, and evaluation as a methodology for deeper learning. Sam stressed again the need for locally relevant and tangible activities. This reminded me of the tenants of situated cognition, where similarly, learning occurs not in isolation but within the local context and environment of our learners. NSTA has a wealth of resources on inquiry-based learning if desired.

Dyson touted the ultimate potential and power of technology, proclaiming that it may enable the kinds of experiences that are powerful enough to engage what students are really thinking, and maybe even powerful enough to change what they believe. Linking this with the notion of connected learning, we need to make sure the experiences we structure make young people want to come back and keep learning. Stronger and more powerful words could not be proffered here. We’ve all heard the term that students need to power-down when coming to school, and all too often our classrooms still resemble the industrial models of the last century where the teacher is at a chalk board performing a lecture demo, and students sit quietly as they complete fill-in-the-blank worksheets. This is not the vision for three-dimensional teaching and learning espoused in the new standards, and with a focus on these strategies being shared at NSTA Conferences, and with speakers like Sam Dyson, they will not be the norm in the years to come. Sam cited one example of Alex S., a student he met through a summer program called “STEAM Studio” in downtown Chicago. Steam Studio is a portable maker studio, with a wall of glass on one side, where outsiders feel “invited” to see and make sense of the experiences as those inside fueled by their intrinsic motivation, create, produce, and inspire. The maker movement indeed exemplifies STEM experiences that ignite student learning. Alex was given the experience of personalized learning that was important to him—fashioning a piece of clothing into something other than its intended purpose.

NSTA has position statements on the Next Generation Science Standards, scientific inquiry, and the role of e-learning in science education; each statement provides easy-to-read, powerful statements about the importance of these topics in teaching and learning.

Connected learning has six learning and design principles, all of which address the need to move to deeper understanding through connections: 1) Interest powered-locally and personally relevant; 2) Peer-supported—not done in isolation; 3) Academically oriented—providing career and civil payoffs, such as badge efforts to recognize achievement; 4) Production-centered—it’s about doing and learning by doing, showcasing, and voting on each others’ accomplishments; 5) Openly networked—many contributors building a gestalt experience including libraries, art institutes, universities, and corporations, all working in concert; and 6) shared purpose.

Dyson shared several examples, and one salient one is the HIVE in Chicago—whose mission is to transform the learning landscape by empowering youth and educators to enact connected learning through a diverse network of civic and cultural institutions. The Hive offers a growing portfolio of programs within a network of more than 65 organizations currently involved (cultural museums, non-profits, and schools). The Hive offers two grant cycles per year to help schools figure out how to create new learning experiences for young folks using technology and media. Be sure to check it out! It’s about “geeking out” and messing around with technology in fun and innovative ways for just-in-time learning on-demand. That said, he also shared the notion of “Techquity,” where just having access to open resources or technology doesn’t mean all have equitable skills to use it effectively.

Convergence Academies are another model Dyson spoke to that engage participatory learning in digitally enriched classrooms. Chicago Public Schools is experimenting with convergence academies at both an elementary and high school, where fewer than 500 kids connect, consume, and create in a cavernous shell of a building exploiting technology and projects that transcend traditional models for student and teacher learning. Teachers design learning experiences with the goal to converge personal relevance, social interaction, personal interest, meaning and engagement, while simultaneously building academic knowledge.

This reminds me of another “mover” in this arena, Chris Edmin, who moves beyond what many do (just tell us what’s wrong with urban education), and instead shares examples such as creating a graffiti tag on a bridge hundreds of feet in the air and getting kids to think about the inverse square law in physics for spraying the paint. He coined the term and has a brief video on “reality pedagogy,” and it rings true here too I think. Basically, reality pedagogy is teaching and learning that is based on the reality of a young person’s experience. Edmin promotes five steps to help urban education: 1) the cipher (co-generative) dialog drawn from hip-hop discourse, 2) co-teaching by students, 3) cosmopolitanism—making those who are disenfranchised feel they play a critical team role in their learning, 4) context-locally relevant, and 5) content.

Finally, in Adler-hack days, Dyson shared how young people and technologists come together and look at things like food deserts in Chicago—where hotspots that is under-resourced partner with coders to create an app to help address problems, where you combine technical skills, civic issues, and youth concerns into meaning projects.

Act 3 and Epilogue: Bringing It Home

Dyson closed by challenging us to think how we might we minimize the transfer of information to shift our focus from consumption to that of creation and how we might seek innovative ways to make learning socially relevant. We struggle against the volume of knowledge we are charged to cover, and in fact, production-centered learning is hampered knowledge-centered learning. Emphasizing a shift from closed to open-ended thinking, how to make student thinking visible is also important. Dyson shared an example that I too observed at conference hosted by Chris Dede from Harvard on mobile-based learning. Audience impressions and shared-knowledge about presentation topic was visible to all in real-time via Twitter falls on screens that ran adjacent to the main screen that showcased the presenters’ content. As a group all were able to see audience reactions, suggested websites from the crowd in real-time, etc. These types of social media-based techniques, when coupled with the targeted probes for particular science concepts, and the real-time feedback from class polls and sharing digital samples of student work, seem worthy of investigation. Dyson gave another idea for consideration: Rather than turning in class papers for grades, could they be posted on a blog, so not only comments from teachers, but also from other students, generated and revealed for all to see?

Dyson closed by suggesting that absolutely, teaching is hard, and technology is not a panacea. We should desire to give kids an irrepressible desire to learn and grow. Let’s recognize this and design connected learning experiences that give hope, not as a means to an end, but a lifestyle. Learning is hard for teachers, too, Dyson expressed. It’s hard to be vulnerable and in that deep valley when struggling to learn new ways of teaching when teachers and students in urban areas also live in vulnerability of violent neighborhoods and poverty. Creating context conducive to learning must include supports and mentors. Creating spaces where it is safe to feel vulnerable for the first time ever. As quoted by John Dewey, from Democracy and Education in 1916: Education is not preparation for life, it is life!

Al Byers, Ph.D., is the Associate Executive Director, Services for the National Science Teachers Association

Al Byers, Ph.D., is the Associate Executive Director, Services for the National Science Teachers Association

To see more from the 2015 National Conference on Science Education in Chicago, March 12–15, please view the #NSTA15 Facebook Album—and if you see yourself, please tag yourself!

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2015 STEM Forum & Expo

2015 Area Conferences

Follow NSTA