Connected Learning at #NSTA15: Emerging Contexts for Deeper Engagement

By Guest Blogger

Posted on 2015-04-10

Featured speaker Sam Dyson invited attendees to join his personal hive in Chicago last month at NSTA’s National Conference on Science Education. Sponsored by the Shell Corporation, Dyson focused on connected learning and emerging contexts for deeper engagement. Set against the backdrop of a three-act play, Dyson modeled the importance of “connectedness” with a community of learners. Dyson’s first teaching experiences transpired in Johannesburg, Africa, where he admitted he did not know much about teaching, but picked up a few things while teaching in Chicago. Working now for the Mozilla Foundation in youth programming, Dyson brought a well-rounded perspective to his session; I was immediately engaged.

From “Oh No” to “Aha”

In Act I, Dyson revealed his first “Aha” moment in teaching, which interestingly came through his first “important failure.” He was facilitating a classroom demonstration about momentum, mass, and inelastic collisions. In the demonstration, the carts “stick together” when they collide as the approaching car overtakes the slower lead cart. Dyson thought his students had an adequate background to predict the outcome (that the carts moving along the same path would collide and stick together as they continued down the track). To Sam’s surprise, as the demonstration unfolded, one of his students refused to believe what he physically observed. Why? Because the student had no background knowledge, reference point, or tangible observations of this phenomenon occurring in his everyday life. Sam eloquently described this as a failed demonstration, but also as the one that created his “aha” moment. For the first time, he saw and understood deeply that the internal thinking and experiences that students bring to the learning environment undergirds future understanding. This discrepant event did not match the student’s sense making of his world. Dyson realized that teaching was not about what we know, but what we believe.

I wonder how many of us also think about our first “aha” moments early in our careers. Sam’s insight early into his career resonated with me, and I suspect many of you, too! We know that a student is not a tabula rasa, or blank slate, onto which we dump knowledge. As demonstrated by research in cognitive learning sciences about how people learn, we live in a dynamic world with rich interactions of science phenomena and engineering design solutions. We seek to make sense of these observations and form personal working theories and reasons for how these things occur in nature or are made by humankind. We form many of these known preconceptions internally, as part of our own “sense-making,” and as research shows, these preconceptions are deeply seated, resistant to change, and hard to overturn. But fear not, there are also research-based strategies to help learners challenge their own internal logic, face it head on, test it, wrestle with it, and see if it holds up! NSTA has several publications that may assist you across the K–12 spectrum. For example, author Page Keeley’s Uncovering Student’s Ideas in Science series draws upon this research and provides formative assessment questions (or probes) to make this internal student thinking visible. Working with teachers and classrooms, she has developed probes for elementary science, as well as physical, life, and Earth/space science. Page also partnered with Richard Konicek-Moran in an upcoming book titled Teaching for Conceptual Understanding in Science (coming off the NSTA Press any day now) that brings field-tested strategies teachers can use immediately in the classroom to empower students’ learning.

Dyson learned early on that Aha moments are not necessarily when we figure out a solution, but when we gain insight into the problems with which students are wrestling. In his presentation, he stressed that such insight is necessary to provide the kind of learning experiences that really allow students to “connect” new information to what they already believe, and that it is important to understand the difference between knowing and understanding. So, while we continually acquire new information from the world around us (knowing), it is critical for students to be able to apply this knowledge in situ, acquiring a deeper understanding (for instance through challenging “discrepant events”). Students progress until they cannot continue with their internal “sense-making” theories and are forced to reshape and change their understanding, thus allowing them to grow again, pushing through these conceptual “sense-making” barriers. Dyson’s ideas for the arc of student understanding reveal an initial upward arc, but then a “trough” as deeper learning becomes more challenging, a larger investment of time, and a commitment is needed to reach the higher deeper learning arc. Dyson contrasted this against the notion of “superficial learning,” which some might equate to mere recall and recognition of facts versus deeper more flexible learning where understanding is applied across multiple areas, such as the cross-cutting concepts espoused in three-dimensional teaching and learning in K–12 Framework for Science Education and the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), concepts such as patterns, cause and effect, systems and systems models, and stability and change to name a few. Indeed what Dyson shared reflects the work of the National Academies and the NGSS, which stresses that deeper learning of the disciplinary core ideas in science occurs as students engage in authentic science and engineering practices, while recognizing cross-cutting concepts like those above. As I was focused on what Sam was sharing, I scanned the room, seeing a sea of heads nod in affirmation. Check out the NSTA NGSS Hub for tools, resources and learning opportunities around the NGSS.

Connected Learning Equals Flexible Learning!

For Act 2, Dyson asked small groups to discuss what they thought the term Connected Learning meant. Interestingly, I informally asked session attendees this question before Sam started his talk, given it was in the title. I asked why attendees selected this session; what did they want to get from the session? The answers might surprise you! Some acknowledged that Shell-sponsored presentations were always informative and came knowing that, by reputation, the talk would be engaging and worthwhile. Others cited the importance of multicultural diversity in our featured sessions and appreciated the diversity of opinion and expertise represented by the selected speaker. Interestingly, several conflated the notion of “connected learning” with the US Department of Education project called “Connected Educators” and had come wanting to learn how to build successful online communities. Many, though, understood the emphasis of the talk on discussing a pedagogical point of view stressing the importance on connecting students’ local environment and the world in which they live to the science concepts we are presenting to help them better understanding the world in which they live. To make connections and be critical thinkers, challenging their internal views and the importance of teachers on structuring these types of experiences.

Dyson shared what many agree with, the importance of a constructivist learning cycle for teaching, and referenced the 5E model developed by BSCS, where students cycle through (not necessarily linearly or within a single period) engagement, exploration, explanation, elaboration, and evaluation as a methodology for deeper learning. Sam stressed again the need for locally relevant and tangible activities. This reminded me of the tenants of situated cognition, where similarly, learning occurs not in isolation but within the local context and environment of our learners. NSTA has a wealth of resources on inquiry-based learning if desired.

Dyson touted the ultimate potential and power of technology, proclaiming that it may enable the kinds of experiences that are powerful enough to engage what students are really thinking, and maybe even powerful enough to change what they believe. Linking this with the notion of connected learning, we need to make sure the experiences we structure make young people want to come back and keep learning. Stronger and more powerful words could not be proffered here. We’ve all heard the term that students need to power-down when coming to school, and all too often our classrooms still resemble the industrial models of the last century where the teacher is at a chalk board performing a lecture demo, and students sit quietly as they complete fill-in-the-blank worksheets. This is not the vision for three-dimensional teaching and learning espoused in the new standards, and with a focus on these strategies being shared at NSTA Conferences, and with speakers like Sam Dyson, they will not be the norm in the years to come. Sam cited one example of Alex S., a student he met through a summer program called “STEAM Studio” in downtown Chicago. Steam Studio is a portable maker studio, with a wall of glass on one side, where outsiders feel “invited” to see and make sense of the experiences as those inside fueled by their intrinsic motivation, create, produce, and inspire. The maker movement indeed exemplifies STEM experiences that ignite student learning. Alex was given the experience of personalized learning that was important to him—fashioning a piece of clothing into something other than its intended purpose.

NSTA has position statements on the Next Generation Science Standards, scientific inquiry, and the role of e-learning in science education; each statement provides easy-to-read, powerful statements about the importance of these topics in teaching and learning.

Connected learning has six learning and design principles, all of which address the need to move to deeper understanding through connections: 1) Interest powered-locally and personally relevant; 2) Peer-supported—not done in isolation; 3) Academically oriented—providing career and civil payoffs, such as badge efforts to recognize achievement; 4) Production-centered—it’s about doing and learning by doing, showcasing, and voting on each others’ accomplishments; 5) Openly networked—many contributors building a gestalt experience including libraries, art institutes, universities, and corporations, all working in concert; and 6) shared purpose.

Dyson shared several examples, and one salient one is the HIVE in Chicago—whose mission is to transform the learning landscape by empowering youth and educators to enact connected learning through a diverse network of civic and cultural institutions. The Hive offers a growing portfolio of programs within a network of more than 65 organizations currently involved (cultural museums, non-profits, and schools). The Hive offers two grant cycles per year to help schools figure out how to create new learning experiences for young folks using technology and media. Be sure to check it out! It’s about “geeking out” and messing around with technology in fun and innovative ways for just-in-time learning on-demand. That said, he also shared the notion of “Techquity,” where just having access to open resources or technology doesn’t mean all have equitable skills to use it effectively.

Convergence Academies are another model Dyson spoke to that engage participatory learning in digitally enriched classrooms. Chicago Public Schools is experimenting with convergence academies at both an elementary and high school, where fewer than 500 kids connect, consume, and create in a cavernous shell of a building exploiting technology and projects that transcend traditional models for student and teacher learning. Teachers design learning experiences with the goal to converge personal relevance, social interaction, personal interest, meaning and engagement, while simultaneously building academic knowledge.

This reminds me of another “mover” in this arena, Chris Edmin, who moves beyond what many do (just tell us what’s wrong with urban education), and instead shares examples such as creating a graffiti tag on a bridge hundreds of feet in the air and getting kids to think about the inverse square law in physics for spraying the paint. He coined the term and has a brief video on “reality pedagogy,” and it rings true here too I think. Basically, reality pedagogy is teaching and learning that is based on the reality of a young person’s experience. Edmin promotes five steps to help urban education: 1) the cipher (co-generative) dialog drawn from hip-hop discourse, 2) co-teaching by students, 3) cosmopolitanism—making those who are disenfranchised feel they play a critical team role in their learning, 4) context-locally relevant, and 5) content.

Finally, in Adler-hack days, Dyson shared how young people and technologists come together and look at things like food deserts in Chicago—where hotspots that is under-resourced partner with coders to create an app to help address problems, where you combine technical skills, civic issues, and youth concerns into meaning projects.

Act 3 and Epilogue: Bringing It Home

Dyson closed by challenging us to think how we might we minimize the transfer of information to shift our focus from consumption to that of creation and how we might seek innovative ways to make learning socially relevant. We struggle against the volume of knowledge we are charged to cover, and in fact, production-centered learning is hampered knowledge-centered learning. Emphasizing a shift from closed to open-ended thinking, how to make student thinking visible is also important. Dyson shared an example that I too observed at conference hosted by Chris Dede from Harvard on mobile-based learning. Audience impressions and shared-knowledge about presentation topic was visible to all in real-time via Twitter falls on screens that ran adjacent to the main screen that showcased the presenters’ content. As a group all were able to see audience reactions, suggested websites from the crowd in real-time, etc. These types of social media-based techniques, when coupled with the targeted probes for particular science concepts, and the real-time feedback from class polls and sharing digital samples of student work, seem worthy of investigation. Dyson gave another idea for consideration: Rather than turning in class papers for grades, could they be posted on a blog, so not only comments from teachers, but also from other students, generated and revealed for all to see?

Dyson closed by suggesting that absolutely, teaching is hard, and technology is not a panacea. We should desire to give kids an irrepressible desire to learn and grow. Let’s recognize this and design connected learning experiences that give hope, not as a means to an end, but a lifestyle. Learning is hard for teachers, too, Dyson expressed. It’s hard to be vulnerable and in that deep valley when struggling to learn new ways of teaching when teachers and students in urban areas also live in vulnerability of violent neighborhoods and poverty. Creating context conducive to learning must include supports and mentors. Creating spaces where it is safe to feel vulnerable for the first time ever. As quoted by John Dewey, from Democracy and Education in 1916: Education is not preparation for life, it is life!

Al Byers, Ph.D., is the Associate Executive Director, Services for the National Science Teachers Association

Al Byers, Ph.D., is the Associate Executive Director, Services for the National Science Teachers Association

To see more from the 2015 National Conference on Science Education in Chicago, March 12–15, please view the #NSTA15 Facebook Album—and if you see yourself, please tag yourself!

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2015 STEM Forum & Expo

2015 Area Conferences

Follow NSTA

Senate Releases Bipartisan Bill to "Fix" No Child Left Behind

By Jodi Peterson

Posted on 2015-04-10

Senate education leaders released their bipartisan draft of the bill to reauthorize the Elementary and Secondary Education Act [No Child Left Behind (NCLB)] on Tuesday, April 7.

The bill, titled Every Child Achieves Act, cuts back on the federal footprint in education by providing more authority to the states and reducing the powers of the Secretary of Education. It retains the current federal testing requirement—students would continue to be tested in English and math in third through eighth grades as well as once in high school, and science tests would also be administered three times between third and 12th grade—but the language does away with the current NCLB accountability provisions and allows states to develop their own accountability systems. The bill also continues to provide federal funding to the states to support teacher and principal professional development and school wrap around services, but allows the state to decide how these funds would be spent.

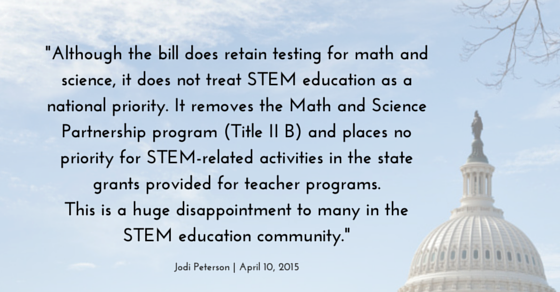

Although the bill does retain testing for math and science, it does not treat STEM education as a national priority. It removes the Math and Science Partnership program (Title II B) and places no priority for STEM-related activities in the state grants provided for teacher programs. This is a huge disappointment to many in the STEM education community.

Mark up for the bill in the Senate HELP Committee is scheduled to begin Tuesday, April 14. At that time, we expect that many amendments—including an amendment on STEM education—will be introduced and considered by the HELP Committee. Stay tuned and watch for upcoming emails from NSTA for the latest news and information, and how you can be involved in the process to rewrite the nation’s federal education law.

- Read the press release from the Senate HELP Committee.

- Read a summary of the bill.

- Read the bill.

- Read and contact Jodi Peterson (jpeterson@nsta.org) to sign your organization on to the STEM Education Coalition advocacy letter.

Here are some of the highlights in the bill.

Standards: Continues the current requirement that States must adopt reading, math, and science standards aligned to college and career readiness. States can decide what academic standards they will adopt without interference from Washington. The federal government may not mandate or incentivize states to adopt or maintain any particular set of standards, including Common Core.

Testing: Annual testing is maintained. Students would be tested in English and math in grades 3-8 and once in high school; science tests would be required to be administered three times between grades 3 and 12. A pilot program would allow states to experiment with “innovative assessment systems” within the state.

Accountability: The bill maintains annual reporting of disaggregated data of groups of children, but ends No Child Left Behind’s accountability system. States would be responsible for determining how to use federally required tests for accountability purposes but will be able to determine the weight of those tests in their systems. States will also be required to include graduation rates, one measure of post-secondary education or workforce readiness, and English proficiency for English learners. States must meet some federal parameters, including ensuring all students and subgroups of students are included in the accountability system, disaggregating student achievement data, and establishing challenging academic standards for all students.

Teacher Evaluations: Would end federal mandates on evaluations and the federal definition of a “highly qualified teacher” and allow states to develop their own teacher evaluation systems if they choose to do so.

Math and Science Education: Eliminates the existing Title II.B Math and Science Partnership Program from Title II. Provides all Teacher Quality Funding to states through formula grants.

Title II Teacher Professional Development: Continues funds to states and districts for teacher and leaders support, including high quality induction programs for new teachers, ongoing professional development opportunities for teachers, and programs to recruit new educators to the profession.

Title I Dollars: Does not allow federal funds that support low-income students to follow students between schools (known as Title I portability).

Title IV: Provides wrap around services to improve students’ safety, health, well-being and academic achievement during and after the school day.

Early Childhood: Includes a provision clarifying states, districts and schools can use Title I, Title II, and Title III ESEA funds to improve early childhood education programs.

Core Academic Subjects: Adds writing, music, computer science, technology, and physical education to the list of disciplines it defines as “core academic subjects.”

Low-Performing Schools: School districts will be responsible for designing evidence-based interventions for low performing schools. The federal government is prohibited from mandating, prescribing, or defining the specific steps school districts and states must take to improve those schools. States monitor interventions implemented by school districts and take steps to further assist school districts if interventions are not effective.

Charter Schools: Updates and strengthens charter school programs by combining two existing programs into one Charter Schools Program.

Rural Schools: Maintains the authorization of the Small, Rural School Achievement Program (SRSA) and the Rural and Low-Income School (RLIS) program.

Reaction to the bill was mostly positive, but mixed. The White House, in a statement, called the agreement an “important step in their bipartisan effort.”

Senator Murray said there’s more work to be done, but the agreement is a “strong step in the right direction,” while Senator Alexander said the bill “continues important measurements of the academic progress of students but restores to states, local school districts, teachers, and parents the responsibility for deciding what to do about improving student achievement. This should produce fewer and more appropriate tests. It is the most effective way to advance higher standards and better teaching in our 100,000 public schools.”

Read the Washington Post article on more reaction to the Senate ESEA draft.

Stay tuned and look for upcoming issues of NSTA Express for the latest information on developments in Washington, DC.

Jodi Peterson is Assistant Executive Director of Legislative Affairs for the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) and Chair of the STEM Education Coalition. e-mail Jodi at jpeterson@nsta.org; follow her on Twitter at @stemedadvocate.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

RSpec-Explorer

By Edwin P. Christmann

Posted on 2015-04-09

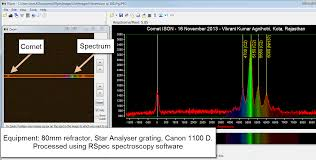

The RSpec-Explorer is a small, portable spectroscopy camera that connects to a computer. It can be used for measuring spectra from light sources (including flames, screens, etc.) and for evaluating the emission signature from gas tubes.

The software package can be downloaded from www.fieldtestedsystems.com/getrex, which offers a free 30-day trial before a license purchase is required. Once downloaded, the camera is connected to a computer via a USB cable. After the USB cable is connected, videos and images can be recorded/captured and saved. Subsequently, both the image from the camera and the corresponding spectra can be viewed simultaneously; from either the saved image/video file or from a live feed. In addition, images can be imported for spectral analysis and the files can be read in both .bmp and .jpeg formats.

Another nice feature is the ability of the RSpec-Explorer to handle FITS data files, which are common in the field of astronomy. Therefore, images captured by NASA’s Hubble telescope and other astronomy sources can be imported and analyzed by allowing you to import and export data points into the program for analysis.

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eLzZwrOBaaU[/youtube]

The spectrograph is also highly customizable with a variety of features that allow the user to select a part of an image or camera view for analysis. Spectral data can be saved on the graph and overlaid with other emission spectra to cfor the sake of comparison. Another nice feature is the zoom features that allow you to get a closer look at different parts of the spectrograph. Once captured, the spectrograph can be saved or copied, and inserted into almost any document type. The camera automatically adjusts for different light inputs and reduces external light noise with several manual adjustments. The device can be calibrated for more precise readings as well.

Overall, the RSpec-Explorer is very easy to use—only minimal setup is required to begin displaying and analyzing spectra. In addition, the wide variety of options for calibration and customization of views gives this device the ability to do precision work. The device is sturdy and functioned well in a classroom setting. The estimated cost for the camera, tripod and software is $395, which make it an affordable choice for teacher demonstrations.

Our thanks to Arbor Scientific for making the Rspec-Explorer available for review.

Edwin P. Christmann is a professor and chairman of the secondary education department and graduate coordinator of the mathematics and science teaching program at Slippery Rock University in Slippery Rock, Pennsylvania, Corissa Fretz is a graduate student and a research assistant in the mathematics and science teaching program at Slippery Rock University in Slippery Rock, Pennsylvania, and Katherine Wingard is a graduate student and a research assistant in the mathematics and science teaching program at Slippery Rock University in Slippery Rock, Pennsylvania

The RSpec-Explorer is a small, portable spectroscopy camera that connects to a computer. It can be used for measuring spectra from light sources (including flames, screens, etc.) and for evaluating the emission signature from gas tubes.

Planning Your Science Curriculum Using NSTA's Quick-Reference Guides to the NGSS

By MsMentorAdmin

Posted on 2015-04-08

Science teachers frequently ask for help using the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) in their work planning curriculum and instruction. As the curator of materials for the NSTA Press book series Quick-Reference Guides to the NGSS, I thought about how NSTA could best help with this broad task. The good news is, we have targeted this series to educators at specific grade levels (K–4, 5–8, 9–12, and K–12), so teachers can find the information packaged in ways that best fits their immediate needs.

The NGSS is made up of four basic parts:

- Practices are the activities in which scientists engage in to understand the world (such as planning an investigation or constructing an explanation).

- Core ideas are useful in understanding the world (such as the laws of motion, phases of the moon, and inheritance of traits).

- Crosscutting concepts, such as patterns and systems, are not specific to any one discipline but cut across them all.

- Performance expectations describe what students should be able to do at the end of instruction. They are specific combinations of the three dimensions upon which the NGSS are built—practices, core ideas, and crosscutting concepts.

When planning instruction, it is important to integrate the three dimensions because the research that prompted the writing of the NGSS (as described in an earlier document called the Framework for K–12 Science Education) indicates that the most effective lessons are those that combine the three dimensions. Because the performance expectations combine the three dimensions, some educators have mistakenly assumed that the performance expectations describe exactly what teachers are expected to do in the classroom. This is not the case! Students need to engage in multiple practices to master the goals of the NGSS, so teachers should develop their own combinations of core ideas and crosscutting concepts for each lesson they teach; they are not limited to the particular combinations of practices, core ideas, and crosscutting concepts described in the performance expectations. The NGSS gives teachers the flexibility to plan learning experiences that best meet their style of teaching and their students’ needs.

Practical Planning

To streamline your planning and guide you in selecting practical combinations, each book in the Quick-Reference Guide series has tables customized for a particular grade or level. A kindergarten teacher, for example, can find all of the performance expectations for Kindergarten on pages 92 and 93 of the for elementary school guide (and these are also included in the K–12 guide). The relevant elements of the disciplinary core ideas are listed alongside each performance expectation. All of the practices on which a kindergarten teacher would need to focus are listed on pages 88 and 89 of the guide, and all of the crosscutting concepts he or she would need are on page 90. Thus, everything a kindergarten teacher would need to have at hand in planning lessons is in a set of tables on six pages.

To streamline your planning and guide you in selecting practical combinations, each book in the Quick-Reference Guide series has tables customized for a particular grade or level. A kindergarten teacher, for example, can find all of the performance expectations for Kindergarten on pages 92 and 93 of the for elementary school guide (and these are also included in the K–12 guide). The relevant elements of the disciplinary core ideas are listed alongside each performance expectation. All of the practices on which a kindergarten teacher would need to focus are listed on pages 88 and 89 of the guide, and all of the crosscutting concepts he or she would need are on page 90. Thus, everything a kindergarten teacher would need to have at hand in planning lessons is in a set of tables on six pages.

For example, imagine Kathy, a kindergarten teacher who is focused on performance expectation K-LS1-1: “Use observations to describe patterns of what plants and animals (including humans) need to survive.” In planning a lesson, Kathy wants to be sure that her students can use their understanding of the needs of organisms to make explanations about events they experience in the world around them (what scientists call phenomena).

On page 91 of the guide, Kathy would find the performance expectation and the corresponding disciplinary core idea: “All animals need food in order to live and grow. They obtain their food from plants or from other animals. Plants need water and light to live and grow.” She starts by planning a lesson focused on the needs of plants. She happens to have a plant that has wilted after being left in dark room during vacation. She decides to have students try to figure out what happens to plants if they don’t have the water or light they need. She therefore examines the practices on pages 89–90 and selects one involving explanation: “Use information from observations (firsthand and from media) to construct an evidence-based account for natural phenomena.”

Finally, because Kathy wants students to understand that this as a cause-and-effect relationship, she flips to page 90 and chooses the crosscutting concept “Events have causes that generate observable patterns.”

Finally, because Kathy wants students to understand that this as a cause-and-effect relationship, she flips to page 90 and chooses the crosscutting concept “Events have causes that generate observable patterns.”

Pulling these three dimensions together, she writes a learning performance that describes her goal for students in the lesson: Construct an explanation based on observations from experiments and an understanding of what plants need to survive, that explains what happens to a plant if it is kept in a dark closet for several weeks. Within the lesson, she shows students the plant that was kept in a dark room for several weeks and asks them to come up with ideas as to why the plant died.

In later lessons, Kathy would encourage students to use other plants to test their ideas for what happened to the plant they initially observed. In planning each lesson, she consults the Quick-Reference Guide for the practices, core ideas, and crosscutting concepts to help her construct a learning performance for the lesson. The overall set of these lessons is designed to prepare students to successfully achieve an assessment targeting the performance expectation.

Everything about NGSS a kindergarten teacher needs in just six pages. A similar collection of tables exists for every grade (or grade span) and every discipline in NGSS.

As you develop your curriculum, we encourage you to share your ideas, send us your questions, and stay up to date on new NGSS developments by visiting the NGSS@NSTA hub. We have a devoted team of teacher-curators who are in the trenches with you, and we welcome your feedback!

Ted Willard is the Director of NGSS@NSTA at the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA). Reach Ted at twillard@nsta.org or via Twitter at @Ted_NSTA.

Ted Willard is the Director of NGSS@NSTA at the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA). Reach Ted at twillard@nsta.org or via Twitter at @Ted_NSTA.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

Professional development strategies

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2015-04-06

I’ve been asked to conduct a science workshop for elementary teachers. Can you suggest fun activities for us? —D., Illinois

I’ve been asked to conduct a science workshop for elementary teachers. Can you suggest fun activities for us? —D., Illinois

I’m concerned about science professional development (PD) that consists of gee-whiz, dazzling “experiments” done by a presenter in front of an audience of teachers. I witnessed such a presentation once. The K-3 teachers all replicated the activity in their classrooms (whether or not it aligned with their grade-level curriculum or was appropriate for the age of the students). I wondered, ““And then what?”“

I hope you’ll do something different to support the teachers. Your workshop should enhance teachers’ knowledge and contribute to their ability to provide interesting and relevant science experiences in a planned and purposeful manner.

It would be helpful to ask about the status of elementary science in the school or district. Is science a “special” subject that meets briefly and infrequently? Is science an integral part of the curriculum? Do teachers have access to basic materials? Does the school library have a collection of science-related books? Is there a way for teachers to collaborate about science, either in person or online? Can you build on the teachers’ previous PD experiences.

Here are a few recent observations and suggestions from a similar question on an NSTA e-mail list:

- Base the activities on one of the NGSS (Next Generation Science Standards) performance expectations. If you’re an NSTA member, you have access to journal articles and other resources that can provide learning experiences and teacher supports.

- It’s been my experience that some teachers are generally and genuinely terrified of approaching science education. I would come up with a list of resources and show them how to access and utilize sources that they may already be comfortable with, such as social media.

- I think teaching teachers to let their students derive their own answers will also take the stress off the teacher[s] and allow them to foster a science community. Show them how to pose a question to their classes and let students go back and forth with their answers and reasoning. They need to know how to be OK with a “wrong” answer, or even no answer.

- You want to make sure you are portraying the type of learning the NGSS encourages in elementary school science. The goal of elementary school science is not to teach a bunch of unrelated activities when there’s time left over from math and reading.

- Keep things simple and relaxed. Use your sense of humor.

- I would suggest focusing on only one activity per grade level. I also like the idea of combining the activity or the discussion with the use of a book.

Based on the last suggestion, you could take advantage of resources in NSTA’s Science and Children journal. The monthly column Teaching with Trade Books suggests two books on a theme (you could substitute similar titles from the school library). For example, the February 2015 column, “Understanding Matter and Energy,” includes a brief discussion of the topic, followed by two lessons (for grades K–2 and 3–5). These 1-2 page lessons are written using the 5E (Engage, Explore, Explain, Elaborate, Evaluate) instructional model. They use simple, readily available materials. There is also a description of how the lessons align with the NGSS and Common Core State Standards.

You could assemble a collection of these columns for the participants, either as printouts or an online list (NSTA members can access the articles online and several years worth are archived). Active participation is essential. Take one or two of them and guide teachers through how you would implement them by having them pretend to be the students. Ask them to share their experiences with similar activities. If you have enough time, teams of teachers could review the activities on their own and present them to the rest of the group. If you have opportunities for follow-up, teachers could share how they implemented them.

A few other suggestions: Ask the school administrator to attend the workshop so that he or she can support and encourage the teachers. Use the appropriate terminology for your activity—not every activity in science is a true “experiment.” And include information on any safety issues related to the activities (the column Safety First appears in every S&C issue, too).

The Power of Questioning: Guiding Student Investigations

By Carole Hayward

Posted on 2015-04-02

“Children are full of questions every day: “Why? How does that work? Why? How do you know?” The science classroom is the perfect place to take advantage of this natural curiosity. Questioning cultivates student engagement and drives instruction throughout the learning process.”

This introduction to NSTA Press authors’, Julie McGough and Lisa Nyberg, new book The Power of Questioning: Guiding Student Investigations sets the stage for their model, Powerful Practices. The model takes questioning in the K–6 classroom to a new level while emphasizing the interconnected nature of instruction. Instead of having your students look for the answer, you allow them to raise other questions as they investigate the topic further.

This introduction to NSTA Press authors’, Julie McGough and Lisa Nyberg, new book The Power of Questioning: Guiding Student Investigations sets the stage for their model, Powerful Practices. The model takes questioning in the K–6 classroom to a new level while emphasizing the interconnected nature of instruction. Instead of having your students look for the answer, you allow them to raise other questions as they investigate the topic further.

This pedagogical picture book is color-coded to indicate the three components of the instructional model:

Questioning is printed in red.

Investigations are printed in blue.

Assessments are printed in purple.

These three aspects are linked, and it is important not to approach the model in a linear fashion. As the authors explain, “when thoughtful questioning is combined with engaging investigations, amazing assessments are produced—just as when red and blue are combined, purple is produced.”

Involving students in the Powerful Practices model requires that you know your students as individuals—each student’s way of understanding the world and way of participating in discussion—and as a group. This will help you create engaging questions and a collaborative environment that supports dynamic discussions, leading to purposeful learning that is applicable to the child’s world.

In the book, the authors ask and answer many questions themselves as they present the model:

Connecting Questions and Learning

- Why is questioning a powerful learning tool?

- Why is questioning important when linking literacy to learning investigations and authentic performance assessments?

- Why does skill in questioning engage students in purposeful standards-based learning?

Developing Questioning Strategies

- What types of questions do I need to ask, and when should I ask them?

- What is wait time?

- What is Depth of Knowledge?

Engaging Students and Teachers

- How do I prepare for the Power of Questioning?

- Who are my students, and how do they think?

- How do I provide opportunities for all students to participate?

Building a Questioning Environment

- How do I build a collaborative learning community to support questioning?

- How do I organize resources to engage all learners?

Engaging in Purposeful Discussion

- How do I implement the Power of Questioning?

- How do I use questioning to engage students in purposeful discussions?

- How do I connect discussions within a unit of study?

- How does questioning create opportunities that lead to deeper investigations and authentic assessments?

The authors provide links and QR codes to videos and audio recordings related to content throughout the book. The first book in a new series, Powerful Practices, this book is also available as an e-book.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

“Children are full of questions every day: “Why? How does that work? Why? How do you know?” The science classroom is the perfect place to take advantage of this natural curiosity. Questioning cultivates student engagement and drives instruction throughout the learning process.”

Materials, safety, life science–Resources in "Science and Children"

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2015-03-31

Children I work with on a weekly basis have been exploring different types of materials as they work with them. Painting with thick or thin consistency paint (see the March 2015 Early Years column), running their hands through a pile of small stones before sending them through a tube, working with ceramic clay formulated for children’s use, and trying new kinds of play dough have provided them with experiences that involve testing the properties of materials. The children have also been making choices about which tool to use to achieve their purpose, measuring using informal units and making models to represent objects.

Children I work with on a weekly basis have been exploring different types of materials as they work with them. Painting with thick or thin consistency paint (see the March 2015 Early Years column), running their hands through a pile of small stones before sending them through a tube, working with ceramic clay formulated for children’s use, and trying new kinds of play dough have provided them with experiences that involve testing the properties of materials. The children have also been making choices about which tool to use to achieve their purpose, measuring using informal units and making models to represent objects.

I used the “Safety First: Safer Science Explorations for Young Children” by Ken Roy in the March 2015 issue of Science and Children to check my materials for safe use by children ages 2-5 years. Of course, the small stones were put away when the children who still “mouth” objects were in the room. Following the column advice, I kept damp paper towels in the area where clay was used to wipe up clay dust before it went airborne.

Alongside this exploration of physical properties and possibilities, we have been growing some squash plants from seeds the children excavated from inside the butternut, kabucha and pumpkin squash fruits. It’s a little early for our location to sprout seeds to put in the garden later unless you have an ultraviolet light to supplement the sunshine on the windowsill. We don’t and we may not have a garden space this year. But we can still explore life science concepts. The Early Childhood Resources Review in the print and digital February 2015 issue of Science and Children describes “Tools of Science Inquiry That Support Life Science Investigations.”

Alongside this exploration of physical properties and possibilities, we have been growing some squash plants from seeds the children excavated from inside the butternut, kabucha and pumpkin squash fruits. It’s a little early for our location to sprout seeds to put in the garden later unless you have an ultraviolet light to supplement the sunshine on the windowsill. We don’t and we may not have a garden space this year. But we can still explore life science concepts. The Early Childhood Resources Review in the print and digital February 2015 issue of Science and Children describes “Tools of Science Inquiry That Support Life Science Investigations.”

I think I’ll make a basket of these items to have at hand for our nature walks and playground time.

![]() The NSTA Learning Center Early Childhood Forum is a great place to post a question asking other educators about a standard, lesson plan or concept. Create an account, and join in the conversations. As I tell the children, “Scientists don’t always agree, and that’s okay. We keep trying to learn, together.”

The NSTA Learning Center Early Childhood Forum is a great place to post a question asking other educators about a standard, lesson plan or concept. Create an account, and join in the conversations. As I tell the children, “Scientists don’t always agree, and that’s okay. We keep trying to learn, together.”

Children I work with on a weekly basis have been exploring different types of materials as they work with them.

Children I work with on a weekly basis have been exploring different types of materials as they work with them.

Climate Change and the Anthropocene

By Becky Stewart

Posted on 2015-03-31

This past winter was extraordinary for many parts of the United States. New England saw unprecedented amounts of snow, while the Sierra Nevada mountains in California, famed for skiing, saw barely any. Lower-than-average snowfalls in the Sierra Nevada over the past several years have created California’s serious drought situation. In Delaware, where I live, we mostly escaped large snow events but temperatures have been below normal and there have been snow flurries in much of the state at the end of March, which are both unwelcome and unusual.

Paleoclimatology Data

Severe droughts, floods, frequent tornadoes, polar vortices, strong monsoons, and record snowfalls are all hallmarks of extreme weather. Scientists think that extreme weather is linked to climate change. There’s also strong evidence that human activities are contributing to extreme weather and probably to climate change. It is true that extreme weather events have been a fact of life on Earth for millions of years. But it is also true that extreme weather events appear to be increasing in both severity and frequency. We know this because of the range of paleoclimatology data available to us.

Paleoclimatology is a field that has ancient roots, beginning with Egyptian recorded observations of drought and flood cycles along the Nile River. The Egyptians marked these events because the Nile floods deposited fertile soil on the fields along the river where much of their food was grown. Evidence is now mounting that a severe drought may have been responsible for the collapse of the Old Kingdom, 4000 years ago. Evidence of similar conditions has been found for Mesopotamia, another ancient civilization, where cities were abandoned at approximately the same time and soil deposits indicate a drought that may have lasted 300 years. A thoughtful review of several recent books by historians on climate change, economics, politics, and human geography can be found here. The books describe the rise and fall of numerous civilizations as a result of changing climate.

How does paleoclimatology inform our current understandings of climate events? Current computer models that are used to predict weather and longer-term climate are populated with the results of paleoclimatological studies. Much of the data gathered in such studies comes from the use of climate proxies to infer what conditions were like thousands or even millions of years ago. Some of these proxies include calcareous organisms such as diatoms, foraminifera, and coral; ice cores, tree rings, and sediment cores.

Sediment cores contain pollen and other evidence of climate and weather events over time. Palynology is the study of pollen in the fossil record. Pollen can tell us what kinds of plants lived in the study area at a particular time. Because certain kinds of plants are adapted for certain kinds of climate, scientists can track climate change over long periods of time by inference using plant pollen.

Another important source of paleoclimatology data comes from polar ice cores that preserve atmospheric oxygen isotope ratios. When sea water evaporates as a result of rising air temperatures, it tends to leave a higher percentage of heavier oxygen isotopes in the ocean. When this water freezers, a record of the higher temperatures is left behind in the ice. Ice cores preserve a wealth of other information such as atmospheric dust, pollen, volcanic ash, and pollution. The current ice core record dates back 800,000 years in Antarctica. But scientists think that there might be ice as much as 1.5 million years old on that continent. Some evidence from ice cores is pointing to a global cooling trend that occurred in the late Holocene (up to about 1800 years ago), ending with the Little Ice Age. Temperatures today are still in fact below long-term global averages.

Some scientists are advocating for the designation of a new geologic era, the Anthropocene, to indicate the effect that human activities have had on Earth’s environment. A working group of stratigraphers is currently developing a scientific basis for this new geologic era. There is active debate about the necessity of a new geologic era as well as what event should be chosen as the start of the Anthropocene. Some scientists feel that the first atomic blast is an appropriate starting point, while others suggest the beginning of agriculture or the start of the Industrial Revolution.

Developing a STEM Unit

To develop a STEM unit around paleoclimatology and its possible relation to current extreme weather events, you might like to include a number of elements. Biology teachers or a local botanical garden can help you determine which terrestrial biome applies to your area and help identify which kinds of pollen might show up in the fossil record for your area. You might be able to compare your local pollen with pollen assemblages from other climate zones. Work with a geography teacher to understand what effect historical weather events such as droughts and floods have had in your area.

A physics teacher could help you understand heat transfer and its effect on ocean circulation. Ocean circulation is the engine of climate, so this concept is at the heart of our current understandings. This is part of the reason why changes in polar ice cover are so concerning for many scientists. The uncertainties around the possible outcomes of melting polar ice highlight the importance of further research and illustrate some of the ethical dilemmas wrapped up in this topic. Your chemistry teacher could contribute background on why isotope ratios can be used to infer changes in Earth’s air temperature over time.

If your district has a computer science program, those teachers can provide examples of some of the sophisticated models used to predict weather and associated climate trends. If you don’t have access to a computer science teacher, a calculus teacher should be able to describe how the models are built. If you’ve got access to a technology lab, you could work on designing and building weather instruments. If you have students who are interested in engineering careers, you could have them investigate the emerging fields of climate engineering and terraforming, which may be used on Mars to make that planet more habitable for people in the future.

There are a number of ethical issues involved in geoengineering and terraforming, and involving English teachers or social studies teachers with an interest in ethics would enrich STEM lessons on climate change. Hard choices may need to be made in the future to ensure our sustainability as a species. Addressing the ethical issues up front will help everyone involved make the best possible decisions. The effects that human activities have had or will have on global climate change are open to debate.

Produced by the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA), science writer Becky Stewart contributes monthly to the Science and STEM Classroom e-newsletter, a forum for ideas and resources that middle and high school teachers need to support science, technology, engineering, and math curricula. If you enjoy these blog posts, follow Becky Stewart on Twitter (@ramenbecky). Fans of the old version of The STEM Classroom e-newsletter can find the archives here.

Follow NSTA