Materials, safety, life science–Resources in "Science and Children"

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2015-03-31

Children I work with on a weekly basis have been exploring different types of materials as they work with them. Painting with thick or thin consistency paint (see the March 2015 Early Years column), running their hands through a pile of small stones before sending them through a tube, working with ceramic clay formulated for children’s use, and trying new kinds of play dough have provided them with experiences that involve testing the properties of materials. The children have also been making choices about which tool to use to achieve their purpose, measuring using informal units and making models to represent objects.

Children I work with on a weekly basis have been exploring different types of materials as they work with them. Painting with thick or thin consistency paint (see the March 2015 Early Years column), running their hands through a pile of small stones before sending them through a tube, working with ceramic clay formulated for children’s use, and trying new kinds of play dough have provided them with experiences that involve testing the properties of materials. The children have also been making choices about which tool to use to achieve their purpose, measuring using informal units and making models to represent objects.

I used the “Safety First: Safer Science Explorations for Young Children” by Ken Roy in the March 2015 issue of Science and Children to check my materials for safe use by children ages 2-5 years. Of course, the small stones were put away when the children who still “mouth” objects were in the room. Following the column advice, I kept damp paper towels in the area where clay was used to wipe up clay dust before it went airborne.

Alongside this exploration of physical properties and possibilities, we have been growing some squash plants from seeds the children excavated from inside the butternut, kabucha and pumpkin squash fruits. It’s a little early for our location to sprout seeds to put in the garden later unless you have an ultraviolet light to supplement the sunshine on the windowsill. We don’t and we may not have a garden space this year. But we can still explore life science concepts. The Early Childhood Resources Review in the print and digital February 2015 issue of Science and Children describes “Tools of Science Inquiry That Support Life Science Investigations.”

Alongside this exploration of physical properties and possibilities, we have been growing some squash plants from seeds the children excavated from inside the butternut, kabucha and pumpkin squash fruits. It’s a little early for our location to sprout seeds to put in the garden later unless you have an ultraviolet light to supplement the sunshine on the windowsill. We don’t and we may not have a garden space this year. But we can still explore life science concepts. The Early Childhood Resources Review in the print and digital February 2015 issue of Science and Children describes “Tools of Science Inquiry That Support Life Science Investigations.”

I think I’ll make a basket of these items to have at hand for our nature walks and playground time.

![]() The NSTA Learning Center Early Childhood Forum is a great place to post a question asking other educators about a standard, lesson plan or concept. Create an account, and join in the conversations. As I tell the children, “Scientists don’t always agree, and that’s okay. We keep trying to learn, together.”

The NSTA Learning Center Early Childhood Forum is a great place to post a question asking other educators about a standard, lesson plan or concept. Create an account, and join in the conversations. As I tell the children, “Scientists don’t always agree, and that’s okay. We keep trying to learn, together.”

Children I work with on a weekly basis have been exploring different types of materials as they work with them.

Children I work with on a weekly basis have been exploring different types of materials as they work with them.

Climate Change and the Anthropocene

By Becky Stewart

Posted on 2015-03-31

This past winter was extraordinary for many parts of the United States. New England saw unprecedented amounts of snow, while the Sierra Nevada mountains in California, famed for skiing, saw barely any. Lower-than-average snowfalls in the Sierra Nevada over the past several years have created California’s serious drought situation. In Delaware, where I live, we mostly escaped large snow events but temperatures have been below normal and there have been snow flurries in much of the state at the end of March, which are both unwelcome and unusual.

Paleoclimatology Data

Severe droughts, floods, frequent tornadoes, polar vortices, strong monsoons, and record snowfalls are all hallmarks of extreme weather. Scientists think that extreme weather is linked to climate change. There’s also strong evidence that human activities are contributing to extreme weather and probably to climate change. It is true that extreme weather events have been a fact of life on Earth for millions of years. But it is also true that extreme weather events appear to be increasing in both severity and frequency. We know this because of the range of paleoclimatology data available to us.

Paleoclimatology is a field that has ancient roots, beginning with Egyptian recorded observations of drought and flood cycles along the Nile River. The Egyptians marked these events because the Nile floods deposited fertile soil on the fields along the river where much of their food was grown. Evidence is now mounting that a severe drought may have been responsible for the collapse of the Old Kingdom, 4000 years ago. Evidence of similar conditions has been found for Mesopotamia, another ancient civilization, where cities were abandoned at approximately the same time and soil deposits indicate a drought that may have lasted 300 years. A thoughtful review of several recent books by historians on climate change, economics, politics, and human geography can be found here. The books describe the rise and fall of numerous civilizations as a result of changing climate.

How does paleoclimatology inform our current understandings of climate events? Current computer models that are used to predict weather and longer-term climate are populated with the results of paleoclimatological studies. Much of the data gathered in such studies comes from the use of climate proxies to infer what conditions were like thousands or even millions of years ago. Some of these proxies include calcareous organisms such as diatoms, foraminifera, and coral; ice cores, tree rings, and sediment cores.

Sediment cores contain pollen and other evidence of climate and weather events over time. Palynology is the study of pollen in the fossil record. Pollen can tell us what kinds of plants lived in the study area at a particular time. Because certain kinds of plants are adapted for certain kinds of climate, scientists can track climate change over long periods of time by inference using plant pollen.

Another important source of paleoclimatology data comes from polar ice cores that preserve atmospheric oxygen isotope ratios. When sea water evaporates as a result of rising air temperatures, it tends to leave a higher percentage of heavier oxygen isotopes in the ocean. When this water freezers, a record of the higher temperatures is left behind in the ice. Ice cores preserve a wealth of other information such as atmospheric dust, pollen, volcanic ash, and pollution. The current ice core record dates back 800,000 years in Antarctica. But scientists think that there might be ice as much as 1.5 million years old on that continent. Some evidence from ice cores is pointing to a global cooling trend that occurred in the late Holocene (up to about 1800 years ago), ending with the Little Ice Age. Temperatures today are still in fact below long-term global averages.

Some scientists are advocating for the designation of a new geologic era, the Anthropocene, to indicate the effect that human activities have had on Earth’s environment. A working group of stratigraphers is currently developing a scientific basis for this new geologic era. There is active debate about the necessity of a new geologic era as well as what event should be chosen as the start of the Anthropocene. Some scientists feel that the first atomic blast is an appropriate starting point, while others suggest the beginning of agriculture or the start of the Industrial Revolution.

Developing a STEM Unit

To develop a STEM unit around paleoclimatology and its possible relation to current extreme weather events, you might like to include a number of elements. Biology teachers or a local botanical garden can help you determine which terrestrial biome applies to your area and help identify which kinds of pollen might show up in the fossil record for your area. You might be able to compare your local pollen with pollen assemblages from other climate zones. Work with a geography teacher to understand what effect historical weather events such as droughts and floods have had in your area.

A physics teacher could help you understand heat transfer and its effect on ocean circulation. Ocean circulation is the engine of climate, so this concept is at the heart of our current understandings. This is part of the reason why changes in polar ice cover are so concerning for many scientists. The uncertainties around the possible outcomes of melting polar ice highlight the importance of further research and illustrate some of the ethical dilemmas wrapped up in this topic. Your chemistry teacher could contribute background on why isotope ratios can be used to infer changes in Earth’s air temperature over time.

If your district has a computer science program, those teachers can provide examples of some of the sophisticated models used to predict weather and associated climate trends. If you don’t have access to a computer science teacher, a calculus teacher should be able to describe how the models are built. If you’ve got access to a technology lab, you could work on designing and building weather instruments. If you have students who are interested in engineering careers, you could have them investigate the emerging fields of climate engineering and terraforming, which may be used on Mars to make that planet more habitable for people in the future.

There are a number of ethical issues involved in geoengineering and terraforming, and involving English teachers or social studies teachers with an interest in ethics would enrich STEM lessons on climate change. Hard choices may need to be made in the future to ensure our sustainability as a species. Addressing the ethical issues up front will help everyone involved make the best possible decisions. The effects that human activities have had or will have on global climate change are open to debate.

Produced by the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA), science writer Becky Stewart contributes monthly to the Science and STEM Classroom e-newsletter, a forum for ideas and resources that middle and high school teachers need to support science, technology, engineering, and math curricula. If you enjoy these blog posts, follow Becky Stewart on Twitter (@ramenbecky). Fans of the old version of The STEM Classroom e-newsletter can find the archives here.

Follow NSTA

Legislative Update

Negotiations Continue on ESEA Rewrite

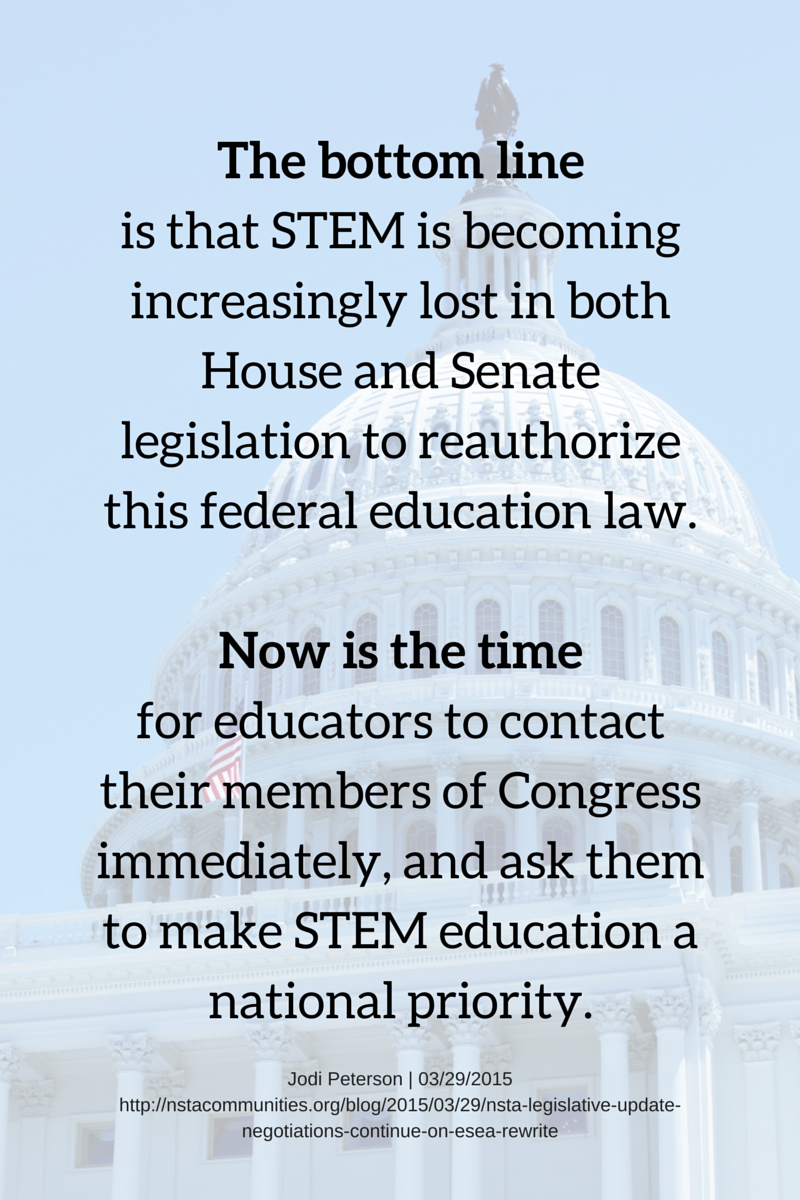

By Jodi Peterson

Posted on 2015-03-29

Bipartisan negotiations continue between the two education leaders in the Senate. Senators Lamar Alexander (R-TN) and Patty Murray (D-WA) have issued a statement that they indeed intend to release their bill to rewrite the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (No Child Left Behind) the week of April 13 (Congress is now off for their two week Easter break). Both are committed to a bipartisan process for the bill, but Senator Alexander has indicated that addressing early childhood programs in the ESEA—a huge priority for the Administration and Senator Murray—will be difficult. At the center of negotiations are the issues of accountability and testing. STEM advocates are continuing to work with offices on both sides to get STEM-specific funding and programs included in this Senate bill.

Bipartisan negotiations continue between the two education leaders in the Senate. Senators Lamar Alexander (R-TN) and Patty Murray (D-WA) have issued a statement that they indeed intend to release their bill to rewrite the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (No Child Left Behind) the week of April 13 (Congress is now off for their two week Easter break). Both are committed to a bipartisan process for the bill, but Senator Alexander has indicated that addressing early childhood programs in the ESEA—a huge priority for the Administration and Senator Murray—will be difficult. At the center of negotiations are the issues of accountability and testing. STEM advocates are continuing to work with offices on both sides to get STEM-specific funding and programs included in this Senate bill.

In the House, Chairman John Kline is working to whip up more Republican support for his ESEA bill, the Student Success Act, after the bill was pulled from the floor following the loss of support from key conservative groups who thought it did not go far enough to erase the federal footprint from K-12 education. On March 24, the Washington Post reported that Kline was still a few votes short to pass the bill.

The bottom line is that STEM is becoming increasingly lost in both House and Senate legislation to reauthorize this federal education law.

Now is the time for educators to contact their members of Congress immediately, and ask them to make STEM education a national priority. At the Legislative Action Center of the STEM Education Coalition website, you can send a letter to your elected representatives, asking them to

- Maintain a strong focus on science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) education.

- Continue the focus on math and science as required elements of any state’s accountability system.

- Provide states with dedicated funding to support STEM-related activities and teacher training.

We need your help getting this message heard and to get as much support as possible for science and STEM education. Please take a moment to write to your elected officials, and send this message to your networks.

And finally, the White House Science Fair was last week. In case you missed it, here is a link to get you caught up. During the event, the President announced new corporate pledges made under the Educate to Innovate initiative. Congratulations again to the teams from ExploraVision and eCYBERMISSION who participated in this year’s White House Science Fair!

Stay tuned and look for upcoming issues of NSTA Express for the latest information on developments in Washington, DC.

Jodi Peterson is Assistant Executive Director of Legislative Affairs for the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) and Chair of the STEM Education Coalition. e-mail Jodi at jpeterson@nsta.org; follow her on Twitter at @stemedadvocate.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

Presentation options

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2015-03-27

One of my goals is for students to communicate what they’re learning in science through presentations. For many of my students, traditional oral reports are overwhelming. I’m looking for authentic, less stressful alternatives. —T., Oregon

One of my goals is for students to communicate what they’re learning in science through presentations. For many of my students, traditional oral reports are overwhelming. I’m looking for authentic, less stressful alternatives. —T., Oregon

One year, I assigned every student a 5-8 minute oral report on a science topic that interested them. I thought I was doing a good job by sharing a template and rubric for the presentation and providing class time for students to prepare. It took several class periods for all of the presentations, and even then some students were not ready. There was a comment sheet for audience members to fill out, but I wasn’t sure the students were engaged enough to justify the time and effort.

So I revisited the original purpose of the assignment to provide opportunities for students to communicate and share what they were learning. This is an authentic goal; most scientists write reports and give presentations at conferences, to potential sponsors, and to the public. It also can be an effective assessment strategy and aligns with the Next Generation Science Standards Science and Engineering practice of “Obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information.”

From my own experience as a presenter, I knew many presentations are done as a team or panel. Most include visuals and use different formats. Some are straightforward lectures; others have activities for participants or opportunities for discussion. I questioned which was most important for my middle schoolers—using an assigned format or engaging in the process of communicating their interests and enthusiasm.

I asked my students how to make this a better experience. They were brutally honest! They wanted to have a choice of formats, work with a partner, and use their creativity. I learned that for some students (for example, English language learners and those with anxiety issues) getting up in front of the class may not be a positive experience, but they still have a lot to share.

So the following year, during a unit on invertebrates, students did presentations in their choice of format, demonstrating something they learned or were excited about. I realized the variety of media and formats made it impossible to use a traditional rubric. But my students did not disappoint!

One girl created an anthology of original poems about these animals. Several students worked on a mural depicting coral reef ecology, a few did traditional term papers, several collaborated on live performances or videos, and one boy who never spoke out in class did an amazing poster on marine arthropods.

His experience made me think more about posters as an alternative to written term papers, too. Many conferences (including NSTA’s) have sharing sessions in which participants summarize their work in a poster display. As the audience circulates around the room (similar to a gallery walk), the presenters explain their work informally instead of getting up in front of everyone and doing a formal speech. Many colleges also use this type of format to showcase student research.

In today’s vocabulary, a poster could also be called an “infographic.” These are more than artistic pictures or dramatic photographs. They present and illustrate data, information, and concepts in such a way that encourages the viewer to make connections or ask questions. (The Periodic Table is an example, and many news services illustrate their articles with visually appealing infographics that include maps, graphs, and illustrations.) At a recent conference session, the presenter described how he uses infographics as bell-ringer discussions, which familiarizes students with effective ones.

Students can use a range of tools to create them, from pencils, markers, and sticky notes on chart paper or a manila folder to online graphic tools and presentation software. I’ve created the resource collection Posters and Infographics in the NSTA resource center with related articles and examples from publications, including two recent NSTA journals. Regardless of the presentation format (poster, infographic, video, or slide show), students need to cite credible sources for their information.

I like projects that reflect a double purpose—the creators engage in the design process and the audience has a product that explains and informs. For example, older students making posters, infographics, or videos for students in the younger grades is a win/win scenario.

There certainly is a place for traditional presentations and reports, but it’s also important for students to learn that there are many effective ways to communicate the results of their investigations.

Meet the People Behind the 2015 NSTA STEM Forum and Expo

By Lauren Jonas, NSTA Assistant Executive Director

Posted on 2015-03-26

The 2015 NSTA STEM Forum and Expo is happening next month in Minneapolis, May 20–23. This unique, STEM-focused event is where informal and formal educators gather to share tools and resources that contribute to successful implementation of STEM education into schools and communities. What makes this so different from any other event of its kind? The people! So here’s a peek behind the scenes at just a few of the people who are collaborating to organize this year’s forum.

Doug Paulson (the home town hero in this bunch!) is a STEM Specialist, Division of Academic Standards and Instructional Effectiveness, in the Minnesota Department of Education.

Doug Paulson (the home town hero in this bunch!) is a STEM Specialist, Division of Academic Standards and Instructional Effectiveness, in the Minnesota Department of Education.

“I am thrilled to welcome NSTA and the STEM Forum to Minnesota, home of innovations such as pacemakers, post-it notes, and most recently, the first personal jet. In addition to the awesome sessions, come and hear from the next generation of Minnesota innovators on the Saturday student panel!

Dedric McGhee is the STEM Manager (Science.Mathematics.Health, Physical Education, and Lifetime Wellness. Shelby County Schools. Memphis, TN)

Dedric McGhee is the STEM Manager (Science.Mathematics.Health, Physical Education, and Lifetime Wellness. Shelby County Schools. Memphis, TN)

“Participating with NSTA and the STEM Forum and Expo has provided me an opportunity to continue to learn and cheer on our community’s work around STEM education. Networking with educational and industry trained STEM professionals provides all of our children a window to future careers and innovations.”

Jennifer C. Williams is the Department Chair Lower School Science at Isidore Newman School in New Orleans, LA.

Jennifer C. Williams is the Department Chair Lower School Science at Isidore Newman School in New Orleans, LA.

“I’m looking forward to the excellent slate of presenters dedicated to helping primary educators develop STEM programs for their schools and their classrooms.”

Kavita Gupta is a High School Strand Leader in the Fremont Union High School District in Sunnyvale, CA.

Kavita Gupta is a High School Strand Leader in the Fremont Union High School District in Sunnyvale, CA.

“As a 16- year veteran of teaching profession , I think STEM is the future of education. NMSI (National Math + Science Initiative) underscores the need of STEM education, ‘The U.S. needs 1 million more STEM professionals over the next decade than it is projected to produce at the current rate.’ We need to align with the STEM education to fulfill this need. I am really excited for the high school strand of STEM forum this year because we have a wide-variety of rich STEM-based lessons for high school teachers, administrators and science liaisons– handpicked from over 100 outstanding proposals.”

Adrienne Gifford is the Innovation & Technology Lab Director at Open Window School in Bellevue, WA (in addition to being a robotics coach and crafter); and she is the Steering Committee Chair for the 2015 STEM Forum & Expo.

Adrienne Gifford is the Innovation & Technology Lab Director at Open Window School in Bellevue, WA (in addition to being a robotics coach and crafter); and she is the Steering Committee Chair for the 2015 STEM Forum & Expo.

“As a former aerospace engineering major, I am SO pumped to see the keynote by Captain Barrington Irving—the youngest person to ever fly solo around the globe! It is so inspiring to have the chance to see someone my own age pursuing their dreams and having such a positive influence on STEM education at the same time!”

Delores Howard is the Assistant Executive Director of Conferences and Meetings at the National Science Teachers Association.

Delores Howard is the Assistant Executive Director of Conferences and Meetings at the National Science Teachers Association.

“When I see teachers coming together and sharing their best ideas and supporting everyone from the newbies to the people making decisions at the highest level, it reminds me how lucky I am to be tied into this fantastic network! “

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2015 STEM Forum & Expo

2015 Area Conferences

One Last Look at #NSTA15 Chicago

To see more from the 2015 National Conference on Science Education in Chicago, March 12-15, please view the #NSTA15 Facebook Album—and if you see yourself, please tag yourself!

Follow NSTA

The 2015 NSTA STEM Forum and Expo is happening next month in Minneapolis, May 20–23. This unique, STEM-focused event is where informal and formal educators gather to share tools and resources that contribute to successful implementation of STEM education into schools and communities. What makes this so different from any other event of its kind? The people! So here’s a peek behind the scenes at just a few of the people who are collaborating to organize this year’s forum.

How Do You Captivate with Current Events?

By Christine Royce

Posted on 2015-03-22

Today is March 22nd which can mean a variety of things to a variety of people. It’s close to the beginning of spring this year; it’s in the middle of March madness, and it is also World Water Day. According to the World Water Day website, this day is “It’s a day to celebrate water. It’s a day to make a difference for the members of the global population who suffer from water related issues. It’s a day to prepare for how we manage water in the future.” While the website has a variety of resources and materials other resources that can be utilized include the following which also appear in this month’s Leaders Letter.

Today is March 22nd which can mean a variety of things to a variety of people. It’s close to the beginning of spring this year; it’s in the middle of March madness, and it is also World Water Day. According to the World Water Day website, this day is “It’s a day to celebrate water. It’s a day to make a difference for the members of the global population who suffer from water related issues. It’s a day to prepare for how we manage water in the future.” While the website has a variety of resources and materials other resources that can be utilized include the following which also appear in this month’s Leaders Letter.

- NPR Article on Taking a Shorter Shower

- Time article on ways to celebrate World Water Day

- Facts and figures are shared by the International Business Times

- Information on sustainable water usage.

While this day is important, it is not the topic of this month’s blog – rather the topic is “which current events do you integrate into your curriculum and how do you do so?” is the topic.

In recent months, the Leaders Letter has featured the following topics in the “Building Content” area:

December 2014 – The Launch of Orion

December 2014 – The Launch of Orion- November 2014 – Brief Encounter with a Comet – The Rosetta Mission

- August 2014 – Ebola – Science in the News

- June 2014 – Science and Soccer – the World Cup

- May 2014 – So what is MERS?

- April 2014 – Mudslides – and the Western US

- February 2014 – Sochi Science – the Olympics

Each of these topics focused on a current event in the news and the application of science to helping solve a problem, investigate a phenomena, or understand what is happening in the world.

Current events often bring the science students are studying to real life and create an interest to explore in more depth and understand more about what is happening, as well as, the science behind it. Current events can be obtained from print, social or digital news sources (and a recommendation is to always verify through multiple sources especially if something is obtained online) thus allowing news to be almost at your fingertips. Discovery News actually has a listing of science topics tagged “current events” which may be of help in finding reading materials for students about a variety of current topics.

Where and how you find the current events topics is part of this question but also what do you do with the topic once found is the second part? Do you utilize a current event topic at the beginning or end of class? Keep a certain day of the week for these topics? Hold the topic until it appropriately fits into your curriculum? Share your ideas with others as you continue this month’s conversation.

A View of #NSTA15 from Down Under

By Guest Blogger

Posted on 2015-03-20

As soon as I saw the space that was allocated for the NSTA conference I knew I was in for something special. To have such a large convention centre dedicated to various forms of professional development over four days is a credit to the American science teachers and the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA), who took the time to put the workshops on.

As soon as I saw the space that was allocated for the NSTA conference I knew I was in for something special. To have such a large convention centre dedicated to various forms of professional development over four days is a credit to the American science teachers and the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA), who took the time to put the workshops on.

The vast choice of workshops available meant there was always a new learning opportunity either on something specifically relevant to my teaching, or something that I was interested in learning more about. The presenters were confident and inspiring, encouraging high standards in the classroom. It is apparent that with the implementation of the NGSS, teachers in America are becoming more willing to think beyond the textbook and incorporate skills that are able to be applied to all facets of life beyond the classroom.

Moving from Textbook to Reality

As STEM becomes more prominent in Australian schools, I feel confident that I can up-skill my colleagues’ approach to their teaching and assist them in constructing lessons and units that engage students with real-world experiences, developing their global competitiveness for the jobs of the future. To have such an amazing educational event keynoted by someone as inspiring as Bill Nye seemed to bring the entire audience together, and perhaps reignited a passion for some teachers encouraging them to be the best they can.

Further to this, the resources available both in the NSTA store and the trade displays are going to greatly assist my lesson development as I have been exposed to data I didn’t know existed. I spent way too much money on books at the NSTA store and if it wasn’t for the weight limit on my flight home I would have bought a lot more. The digital resources that I have discovered thanks to both workshops and trade displays are amazing, and they are going to assist me in bringing global data to the classroom. I have already started to share these with my colleagues back home and I am excited to incorporate them into my teaching programs.

I am very thankful for this experience, and appreciate how welcoming all the NSTA staff were, and all the effort they went to to make the experience worthwhile. I look forward to the strong partnerships that have been forged with the Australian Science Teachers Association and though I may never be fortunate enough to attend another NSTA I will always remember the passion I saw in my international colleagues and I will use that as inspiration create relevant, supportive environments for science education.

Today’s Guest Blogger is Ashley Mulcahy, Glenwood High School, Science Staff, Foreman Avenue & Glenwood Park Drive, Glenwood New South Wales 2768

Editor’s Note: NSTA is grateful for this international view of our conference and learns so much from those beyond our borders. Thank you, Ashley! Should you ever require a member of the NSTA social media staff to attend an Australian conference, don’t hesitate to ask…

To see more from the 2015 National Conference on Science Education in Chicago, March 12-15, please view the #NSTA15 Facebook Album—and if you see yourself, please tag yourself!

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2015 STEM Forum & Expo

2015 Area Conferences

Follow NSTA

Crosscutting concepts

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2015-03-20

Themes, big ideas, unifying concepts—as the editor of Science Scope writes, the idea of crosscutting concepts in science is not a new one. (See the guest editorial Interdisciplinary Science: A Fresh Approach From the Past in Science Scope) But what is new in the NGSS is how the concepts integrate with science/engineering practices and disciplinary core ideas and also transcend grade levels and traditional subject areas. Many of us teachers are (or have been) challenged to connect these three dimensions in a planned and purposeful way. Fortunately for us, the NSTA journals each month provide examples and suggestions.

Science Scope—Embedding Crosscutting Concepts

Science Scope—Embedding Crosscutting Concepts

“Engineering inspired by nature is just one approach you can use to incorporate the NGSS crosscutting concept of Structure and Function into your science curriculum.”

Here are some SciLinks with content information and suggestions for additional activities and investigations related to this month’s featured articles:

- Bringing Historical Scientific Arguments Back to Life: The Case of Continental Drift [SciLinks: Continental Drift, Plate Tectonics]

- Why Theories Do Not Turn Into Laws [SciLinks: Inference]

- For the Love of Infographics [SciLinks: Natural Selection, Adaptations of Animals, Adaptations of Plants]

- Understanding the Art in Science and the Science in Art Through Crosscutting Concepts [SciLinks:

- The Surprising Patterns of Health and Disease [SciLinks: Blood Type, Health Hazards]

- Everyday Engineering: Budding Sound Engineers: Listening to Speakers and Earbuds [SciLinks: Sound]

Science & Children—Structure and Function

Science & Children—Structure and Function

As the editor suggests, this crosscutting concept is at the heart of engineering projects, including those that elementary students enjoy doing–building things and taking things apart. But structure and function are also important when studying other topics such as plants, animals, and the structure of the earth.

Here are some SciLinks with content information and suggestions for additional activities and investigations related to this month’s featured articles:

- Inviting Engineering Into the Science Lab [SciLinks: States of Matter, Sound]

- Our Garden Plot Thickens [SciLinks: Soil Types]

- Blade Structure and Wind Turbine Function and Engineering Encounters: Am I Really Teaching Engineering to Elementary Students? [SciLinks: Wind Currents, Wind Energy]

- Bringing Your Classroom to Life [SciLinks: Characteristics of Living Things]

- Inventing Mystery Machines [SciLinks: Motion-Speed Relationship, Simple Machines]

- Teaching Through Trade Books: Every Part Has a Purpose [SciLinks: Design, Inventors]

- The Early Years: Getting Messy With Matter [SciLinks: Matter]

- Formative Assessment Probes: Soil and Dirt: The Same or Different? [SciLinks: Exploring Soil, What is soil?]

- Methods and Strategies: Bringing the Outside In [SciLinks: Plants]

The Science Teacher—Energy

The Science Teacher—Energy

Energy is not just a content topic in physics. It truly is a crosscutting concept across all disciplines—life sciences (photosynthesis, respiration, ecosystems), chemistry, and Earth science (plate tectonics, earthquakes, ocean currents, weather).

Here are some SciLinks with content information and suggestions for additional activities and investigations related to this month’s featured articles:

- Finding the CO2 Culprit [SciLinks: Climate Change, Volcanic Eruptions, Natural Hazards and Disasters]

- Policy, Literacy, and Energy [SciLinks: Energy Transformations, Energy Conservation, Renewable and Nonrenewable Energy, Sources of Energy]

- Sampling in the Snow [SciLinks: Snowflakes, Albedo, Insulation]

- Our Town [SciLinks: Alternative Energy Sources, Alternative Fuels]

- Fields of Fuel [SciLinks: Sustainable Agriculture]

Themes, big ideas, unifying concepts—as the editor of Science Scope writes, the idea of crosscutting concepts in science is not a new one. (See the guest editorial Interdisciplinary Science: A Fresh Approach From the Past in Science Scope) But what is new in the NGSS is how the concepts integrate with science/engineering practices and disciplinary core ideas and also transcend grade levels and traditional subject areas.

Building NGSS Capacity at #NSTA15

By Guest Blogger

Posted on 2015-03-19

The 2015 NSTA National Conference on Science Education (held in Chicago, March 12-15) was a great opportunity for educators to build their capacity for understanding and implementing the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). In Thursday’s featured presentation (The Key to Implementing the NGSS? Teachers!), Dr. Stephen Pruitt described this capacity-building journey as a path toward expertise: gaining knowledge but also pairing that knowledge with the information on how to use it. In Chicago, NSTA offered NGSS sessions for everyone, covering the spectrum of experience with the Next Generation Science Standards.

The 2015 NSTA National Conference on Science Education (held in Chicago, March 12-15) was a great opportunity for educators to build their capacity for understanding and implementing the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). In Thursday’s featured presentation (The Key to Implementing the NGSS? Teachers!), Dr. Stephen Pruitt described this capacity-building journey as a path toward expertise: gaining knowledge but also pairing that knowledge with the information on how to use it. In Chicago, NSTA offered NGSS sessions for everyone, covering the spectrum of experience with the Next Generation Science Standards.

2015 National Conference Learning

In Thursday’s Featured Presentation, Dr. Pruitt described three key innovations of the Next Generation Science Standards–3-Dimensional learning, the shift toward students being engaged in explaining phenomena and designing solutions, and the integration of engineering with the nature of science. The conference offered over 350 sessions to learn about these key innovations and move the standards into practice. Conference attendees had opportunities to learn from the NGSS and Framework writers, science specialists, post-secondary researchers, and classroom educators.

On Friday NSTA hosted a series of presentations called the 2015 NGSS@NSTA Forum. Dr. Joe Krajcik facilitated one of my favorite forum sessions (Developing and Evaluating Three-Dimensional Curriculum Materials). During our time with Dr. Krajcik, we were immersed in NGSS experiences involving models, reflection, table talk, metacognition, and practicing all the elements of expertise. An important take-away for the group was that this “figuring out” using all 3 dimensions by explaining or creating a model continues to build throughout the lessons facilitating the deep understanding of science.

Many of the NGSS “rock stars” describe the result of NGSS learning as creating a complete picture for the student as opposed to presenting the student with discrete pieces of information. There were so many wonderful NGSS-focused sessions presented by teachers sharing how they are translating NGSS into classroom teaching and learning. For example, Jaclyn Austin and Emily Perry shared their Stormwater Literacy Project as part of the Natural Resources, Natural Partnerships strand incorporating the NGSS and helping students use the science they learn to impact change. The NGSS share-a-thon session on Saturday morning brought together a room full of NGSS resources and opportunities to impact classrooms.

Post-Conference Learning

A critical element to any great professional learning experience is the opportunity to put new learning into practice and reflect on product and results, as well as find on-going support. For those new to the NGSS, Achieve announced the release of a series of videos around the NGSS developed in partnership with the Teaching Channel. Educators can use these videos to continue learning about the three dimensions of the NGSS and how they work together. For those ready to design NGSS lessons and units or to evaluate existing materials to see if they are NGSS aligned, the EQuIP rubric developed in a partnership between NSTA and Achieve is a tool to encourage reflection and conversation among educators working together to develop and evaluate instructional products. The NGSS@NSTA Hub is a one-digital destination to support teaching and learning of the Next Generation Science Standards. NSTA offers more than 80 resources (not counting their journal articles) to support teachers in understanding the NGSS and implementing the standards.

In addition to resources and tools, educators need opportunities to have conversations and share ideas, stories, and curriculum. As the NGSS featured presentation title indicates, the key to implementing NGSS is teachers. Every teacher has a story to share and should be a part of the national conversation and work building curriculum around the NGSS. There are rich communities like the #NGSSchat PLN (Professional Learning Network) and the #NGSSblogs Project that offer ongoing support, conversation, and opportunity to share and receive feedback about the frontline implementation of NGSS: the science classroom and the programs and PD that support it. There are multiple ways to access and join #NGSSchat and the #NGSSblogs project. Learn more at http://www.ngsspln.com/.

In addition to resources and tools, educators need opportunities to have conversations and share ideas, stories, and curriculum. As the NGSS featured presentation title indicates, the key to implementing NGSS is teachers. Every teacher has a story to share and should be a part of the national conversation and work building curriculum around the NGSS. There are rich communities like the #NGSSchat PLN (Professional Learning Network) and the #NGSSblogs Project that offer ongoing support, conversation, and opportunity to share and receive feedback about the frontline implementation of NGSS: the science classroom and the programs and PD that support it. There are multiple ways to access and join #NGSSchat and the #NGSSblogs project. Learn more at http://www.ngsspln.com/.

Tricia Shelton is a High Science Teacher and Teacher Leader with a BS in Biology and MA in Teaching, who has worked for 19 years in Kentucky driven by a passion to help students develop critical and creative thinking skills. Tricia is a 2014 NSTA Distinguished Teaching Award winner for her contributions to and demonstrated excellence in Science Teaching. As a Professional Learning Facilitator and NGSS Implementation Team Leader, Tricia has worked with educators across the United States to develop Best Practices in the Science and Engineering classroom through conference presentations, webinars, coordinating and co- moderating #NGSSchat on Twitter, and virtual and face to face PLC work. Tricia’s current Professional Learning Facilitation includes work around the Next Generation Science Standards and helping STEM students develop the 21st Century Skills of critical and creative thinking, collaboration and communication (including Social media and Video) and Project-Based Learning. Since 2011, she has conducted action research in her classroom to develop effective and accessible instructional and assessment strategies incorporating Best Practice in the STEM classroom, including work for the Marzano Research Laboratory. Through a partnership with BenchFly, the premier science video production platform, she works with CEO, Dr. Alan Marnett, to reinvent scientific education and communication with video. Find Shelton on Twitter @TdiShelton.

Tricia Shelton is a High Science Teacher and Teacher Leader with a BS in Biology and MA in Teaching, who has worked for 19 years in Kentucky driven by a passion to help students develop critical and creative thinking skills. Tricia is a 2014 NSTA Distinguished Teaching Award winner for her contributions to and demonstrated excellence in Science Teaching. As a Professional Learning Facilitator and NGSS Implementation Team Leader, Tricia has worked with educators across the United States to develop Best Practices in the Science and Engineering classroom through conference presentations, webinars, coordinating and co- moderating #NGSSchat on Twitter, and virtual and face to face PLC work. Tricia’s current Professional Learning Facilitation includes work around the Next Generation Science Standards and helping STEM students develop the 21st Century Skills of critical and creative thinking, collaboration and communication (including Social media and Video) and Project-Based Learning. Since 2011, she has conducted action research in her classroom to develop effective and accessible instructional and assessment strategies incorporating Best Practice in the STEM classroom, including work for the Marzano Research Laboratory. Through a partnership with BenchFly, the premier science video production platform, she works with CEO, Dr. Alan Marnett, to reinvent scientific education and communication with video. Find Shelton on Twitter @TdiShelton.

Read Shelton’s previous blog: The Next Generation Science Standards: a transformational opportunity

To see more from the 2015 National Conference on Science Education in Chicago, March 12-15, please view the #NSTA15 Facebook Album—and if you see yourself, please tag yourself!

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2015 STEM Forum & Expo

2015 Area Conferences

Follow NSTA

The 2015 NSTA National Conference on Science Education (held in Chicago, March 12-15) was a great opportunity for educators to build their capacity for understanding and implementing the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS).

The 2015 NSTA National Conference on Science Education (held in Chicago, March 12-15) was a great opportunity for educators to build their capacity for understanding and implementing the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS).

Moticam X

By Edwin P. Christmann

Posted on 2015-03-19

Moticam X

We live in an age where iPads and cell phones are part of the everyday fabric of high school life. With this being the case, Swift Optical’s Moticam X has a great deal of promise as a scientific instrument that can connect a classroom microscope to a variety of portable technologies. As an added bonus, the Moticam X allows you to stretch your science budget by putting students’ personal devices to use instead of investing in a classroom set of new technology. The kit includes:

- A focusable lens

- Variable size eyepiece couples

- Removable mini-USB cable

- USB charger

- C-ring

- Macro-tube

- Motic calibration slide with 4 circles and cross hair

- Motic software and free apps for tablets

The Moticam X is a digital camera that can be used on its own for macro images or attached to the eyepiece of a microscope. Once in place, the digital camera streams high-resolution images to wifi-enabled devices such as smart phones, tablets, and laptops. The Moticam X device can stream images to up to six different devices at the same time, which is excellent for a typical lab station sizes. The streaming image is 1.3 megapixels, which is appropriate for viewing on screen.

The procedure to set up the Moticam X is very straightforward. First, prior to attaching the Moticam X, I focused a microscope on a prepared slide. Next, I attached the Moticam X to the eyepiece of my microscope using a coupler that comes with the device. (If you prefer, you can attach the Moticam X to a goose-neck clamp and use it without the benefit of the microscope’s magnification.) Once the Moticam X was in place, I connected my iPad to the Moticam X by searching for it under the list of available wi-fi connections under the Settings tab. Once I established this connection I launched the app associated with the device and was able to view the slide on which the microscope was focused The device comes with software to help you connect to other wireless devices your students might be using. A router is not required.

Users can view live images, but can also save images to their portfolios. They can then use the apps image editing tools to modify, annotate, and share images. The app also comes with camera settings that allow users to make adjustments for lighting conditions (fluorescent, daylight, LED, etc.) and change the brightness, hue, color saturation, and other basic settings. You can also flip and mirror the image using the camera controls

Overall, I think this is a first-rate device that enhances the capabilities of a microscope and facilitates lab work. In addition, students can save images on portable devices and refer to them when completing homework and other assignments outside the classroom. The Moticam X is a reasonably priced and well-built device that enhances the applications of microscope viewing by integrating Wi-Fi applications to connect microscopes with modern technologies. Undoubtedly, this is the kind of the application that will help students use technology for learning and give them an opportunity to collaborate outside the classroom.

Specifications

Manufacturer: Swift Optical

Price: $449.00

Website: http://swiftoptical.com/products/d-moticam-x

Demonstration: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J38hlQAuW98

Edwin P. Christmann is a professor and chairman of the secondary education department and graduate coordinator of the mathematics and science teaching program at Slippery Rock University in Slippery Rock, Pennsylvania.