Bridging to the Next Generation Science Standards—What's in It for Me?: Featured Strand at NSTA Conference in Portland, OR, October 24-26, 2013

By Lauren Jonas, NSTA Assistant Executive Director

Posted on 2013-09-13

This October, the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) will feature a special strand “Bridging to the Next Generation Science Standards—What’s in It for Me?” at our Conference on Science Education in Portland, OR, October 24-26, 2013. NSTA recognizes that we are at a pivotal point in science education with the release of the NRC Framework and the Next Generation Science Standards. This strand is intended to move educators along the continuum from awareness to an understanding of the NRC Framework and NGSS to implement instructional strategies that help students acquire the skills and knowledge to thrive in a global economy.

- Meeting the Next Generation Science Standards Through Engineering Contexts

- MY NASA DATA: Incorporating SciencePractices in the Classroom

- The NGSS—Make Your Lessons 3-D!

- Engineering Practices: Constructing Ideas for Elementary Teachers

- Using a Patterns Approach to Meet the NGSS in Physics

- Using Picture Books for Professional Development on the Next Generation Science Standards

- Elementary Science Teaching: A Path Toward Content Mastery, Confidence, and Competence

Want more? Check out more than 400 sessions and other events with the Portland Session Browser/Personal Scheduler at http://www.nsta.org/conferences/2013por/.

This October, the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) will feature a special strand “Bridging to the Next Generation Science Standards—What’s in It for Me?” at our Conference on Science Education in Portland, OR, October 24-26, 2013. NSTA recognizes that we are at a pivotal point in science education with the release of the NRC Framework and the Next Generation Science Standards.

Bridging Elementary and Secondary Science and the Common Core: Featured Strand at NSTA Conference in Portland, OR, October 24-26, 2013

By Lauren Jonas, NSTA Assistant Executive Director

Posted on 2013-09-12

This October, the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) will feature a special strand “Bridging Elementary and Secondary Science and the Common Core” at our Conference on Science Education in Portland, OR, October 24-26, 2013. Adopted by most states, the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) must be supported by all content areas, and NSTA recognizes how important this is. Science is a valuable tool for moving forward with Common Core instruction. Science requires the use of strong communication and mathematical skills and will help students improve within these areas. This strand will increase participants’ understanding and ability to link science with the CCSS.

- Tsunami in a Box

- College Ready with Mathematics and Physics

- The Pictures Aren’t There Just to Take Up Space—Getting Kids Good at Reading in Science

- What! We Have to Teach English, Too?

- Bridging Elementary Science for English Learners

- Energy Debates Can Fuel the Common Core!

- What Does Science Have to Do with Math? Interdisciplinary Team Teaching FUN!

- Authentic Writing with Children’s Books: Learning Science from Mr. Fluffy Mittens!

Want more? Check out more than 400 sessions and other events with the Portland Session Browser/Personal Scheduler at http://www.nsta.org/conferences/2013por/.

This October, the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) will feature a special strand “Bridging Elementary and Secondary Science and the Common Core” at our Conference on Science Education in Portland, OR, October 24-26, 2013. Adopted by most states, the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) must be supported by all content areas, and NSTA recognizes how important this is. Science is a valuable tool for moving forward with Common Core instruction.

Science of Golf: friction and spin

By admin

Posted on 2013-09-11

It’s the Sunday round on TV and the leader lands short of the green. He (or she) pulls out a wedge and gives the ball a mighty whack. The ball lands well past the pin, then suddenly starts spinning backwards! Before you know it, the ball has snugged up to the hole. How do they do that???

It’s the Sunday round on TV and the leader lands short of the green. He (or she) pulls out a wedge and gives the ball a mighty whack. The ball lands well past the pin, then suddenly starts spinning backwards! Before you know it, the ball has snugged up to the hole. How do they do that???

In a word—grooves. Find out more about the role of grooves in the Science of Golf: Friction and Spin. This NBC Learn video series, produced in partnership with the United States Golf Association (USGA) and Chevron, will fill you in on the science behind both amazing (and errant) golf shots. The series will also give you a leg up on the technology, engineering, and math associated with the sport for real-world, engaging STEM activities.

Like other NBC Learn video series, the Science of Golf is available cost-free on www.NBCLearn.com. The companion NSTA-developed lesson plans give you a lot of ideas for how to use the videos as a centerpiece, or simply incorporate them into what you already do. This particular one includes guidance for both a hands-on inquiry and investigation using media resources.

We really look forward to hearing about how they worked for you in real-world classrooms. Just leave a comment.

–Judy Elgin Jensen

Image of grooves on a Cleveland wedge courtesy of dennisborn.

Video

SOG: Friction and Spin discusses the importance of being able to impart spin to a golf ball and how friction with the club head is the force that makes this possible.

STEM Lesson Plan—Adaptable for Grades 7–12

The lesson plan provides ideas for STEM exploration plus strategies to support students in their own quest for answers and as well as a more focused approach that helps all students participate in hands-on inquiry.

The SOG: Friction and Spin lesson plan describes how students might investigate a question about how one might design a way to impart backspin and use this backspin to control the motion of the ball after it lands on a surface. A media research option guides students in exploring how groove technology became a point of controversy after a USGA ruling.

You can use the following form to e-mail us edited versions of the lesson plans: [contact-form 2 “ChemNow]

It’s the Sunday round on TV and the leader lands short of the green. He (or she) pulls out a wedge and gives the ball a mighty whack. The ball lands well past the pin, then suddenly starts spinning backwards! Before you know it, the ball has snugged up to the hole. How do they do that???

It’s the Sunday round on TV and the leader lands short of the green. He (or she) pulls out a wedge and gives the ball a mighty whack. The ball lands well past the pin, then suddenly starts spinning backwards! Before you know it, the ball has snugged up to the hole. How do they do that???

Merging Literacy into Science Instruction: Featured Strand at NSTA Conference in Charlotte, NC, November 7-9

By Lauren Jonas, NSTA Assistant Executive Director

Posted on 2013-09-11

This November, the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) will feature a special strand “Merging Literacy into Science Instruction” at our Conference on Science Education in Charlotte, NC, November 7-9. NSTA recognizes that the growing demands on the school day mean that educators sometimes cannot afford to teach science as a separate subject. This strand focuses on authentic ways to integrate the Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects with science instruction. Through sessions given at this conference, attendees will learn to help their students become adept at using such Common Core skills as gathering information, evaluating sources, citing materials accurately, and reporting findings from their research and analysis of sources in a clear and cogent manner.

Sessions organized around this strand include a featured presentation on Friday, November 8, 9:30–10:30 a.m. (“Speaking, Listening, and Learning in Science—Supporting Conceptual Change Through Science Talk”) by Page Keeley, Educator, Writer, and Public Speaker, and 2008–2009 NSTA President. More sessions on merging literacy into science instruction include the following:

- Solar Energy—Let the SUNSHINE In!

- Disciplinary Literacy in Middle School Science: Reading, Writing, and Talking as Active Learning Processes

- Introducing the ChemMatters Compilation Project

- Rev It Up! Energize Science and Literacy Connections

- Science and Literacy: A Natural Fit

- Literacy and iPads—Where Technology Meets the Science Textbook

- Science Vocab Out of the Box: Unique Ways to Help Students Master Vocab

- Nanotechnology in Elementary and Middle School, Oh My

Want more? Check out more than 400 sessions and other events with the Charlotte Session Browser/Personal Scheduler at http://www.nsta.org/conferences/2013cha/.

This November, the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) will feature a special strand “Merging Literacy into Science Instruction” at our Conference on Science Education in Charlotte, NC, November 7-9. NSTA recognizes that the growing demands on the school day mean that educators sometimes cannot afford to teach science as a separate subject.

California's Decisions Show that NGSS is State Driven

By MsMentorAdmin

Posted on 2013-09-09

The California State Board of Education unanimously adopted the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) this week, making it the sixth state to do so. The decision not only represents a move forward for evidence-based science instruction but also highlights the control and flexibility individual states have in terms of the NGSS.

The NGSS was developed by states and was designed for states. Despite erroneous claims that NGSS (and the Common Core) are unfair mandates from the federal government. California was one of twenty-six states that oversaw the development of NGSS and they made decisions about its structure.

These lead states collectively made decisions about the overall scope and structure of the standards. For example, they agreed that while the standards should specify what students must learn each year in the elementary grades, states should have flexibility in what topics are studied each year in middle school and high school.

Some educators believe that students are best served when they study some life science, some Earth science, and some physical science each year. Such an approach allows simpler ideas in each discipline to be studied in earlier grades and more complex ideas in each discipline to be studied in later grades. Topics can be sequenced to build upon and one another over several grades. In addition, this approach presents students with the full variety of science every year.

Others believe that students are best served when they focus on a particular topic every year. as this allows students to see the coherence of ideas within that discipline. In addition, since teachers often have expertise in one discipline but not others, this approach makes it more likely that students are taught by someone with a deep conceptual understanding of the topic.

My point here isn’t about which of these approaches is best; both have their merits. Instead, I want to point out that the developers of NGSS recognized that these decisions are better left to the states. Appendix K of the standards provides model course maps for either of these configurations. More important, the appendix walks through the process of how the NGSS writers developed the model course maps so that states would have guidance about how to do the process themselves.

What does this have to do with California? The board deferred until November on deciding the sequencing of science topics in middle school. Currently in California, the sixth grade curriculum focuses on Earth science, the seventh grade curriculum focuses on life science, and eighth grade curriculum focuses on physical science. A panel of experts in the state recommended an integrated approach where students in each grade would study some of each discipline.

To reiterate the point: When a state chooses to adopt NGSS, THE STATE IS MAKING A CHOICE. NO ONE IS MAKING THE STATE DO ANYTHING.

Furthermore, when the state chooses to adopt NGSS, there are many other choices that must be made. One of these is to choose how courses will be structured in middle school. But there are other choices as well about assessments, professional development, and curriculum materials.

Choosing NGSS is just the first step in a process that can lead better instruction for all students.

So I congratulate California for choosing to adopt NGSS, and I am happy for the students in California because regardless of whether they are taught only one science discipline each year of middle school or a blend of several disciplines each year, they will now have the opportunity to study science more deeply with these standards.

I encourage other states to make the same choice for the benefit of their children.

The California State Board of Education unanimously adopted the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) this week, making it the sixth state to do so. The decision not only represents a move forward for evidence-based science instruction but also highlights the control and flexibility individual states have in terms of the NGSS.

Science of Golf: scoring

By admin

Posted on 2013-09-09

Is a series of single digit numbers really that hard to mentally add up? Seems that many high school golfers think so. Even as a senior excelling in calculus, my golfer daughter and her competitors would whip out their cell phone calculators after a round to add up their scores… for 9 holes!

Is a series of single digit numbers really that hard to mentally add up? Seems that many high school golfers think so. Even as a senior excelling in calculus, my golfer daughter and her competitors would whip out their cell phone calculators after a round to add up their scores… for 9 holes!

It’s really not that hard, however, as evidenced by the NBC Learn video Science of Golf: Math of Golf Scoring, produced in partnership with the United States Golf Association (USGA) and Chevron. Use the video to explore the mental math, number lines, and positive/negative numbers with your students.

Take a look at all of the videos in the Science of Golf series and see which ones will boost your STEM efforts. The videos are available cost-free on www.NBCLearn.com. Don’t have time to play all of them and the synopsis in this blog series just isn’t quite enough information? Open the video and, on the viewer window or Cue Card, you’ll see a Transcript tab. Click that and you’ll find the verbatim transcript of the video. Scan the transcript for a quick overview of what’s in store. You can also “select all” and copy/paste into a document for later reference.

We hope you will try them out. When you do, please leave comments below each posting about how well the information worked in real-world classrooms. And if you had to make significant changes to a lesson, we’d love to see what you did differently, as well as why you made the changes. Leave a comment, and we’ll get in touch with you with submission information.

–Judy Elgin Jensen

Image of his first time to break 80, courtesy of Joe Cascio.

Video

SOG: Math of Golf Scoring how golf scores are tabulated and totaled, and introduces the concept of par. It also shows alternate methods of calculating scores, including that of adding up the differences relative to par, whether positive (over par) or negative (under par).

STEM Lesson Plan—Adaptable for Grades 7–12

The lesson plan provides ideas for STEM exploration plus strategies to support students in their own quest for answers and as well as a more focused approach that helps all students participate in hands-on inquiry.

The SOG: Math of Golf Scoring lesson plan describes how one might compare different mathematical methods of scoring or averaging data.

You can use the following form to e-mail us edited versions of the lesson plans: [contact-form 2 “ChemNow]

Is a series of single digit numbers really that hard to mentally add up? Seems that many high school golfers think so. Even as a senior excelling in calculus, my golfer daughter and her competitors would whip out their cell phone calculators after a round to add up their scores… for 9 holes!

Is a series of single digit numbers really that hard to mentally add up? Seems that many high school golfers think so. Even as a senior excelling in calculus, my golfer daughter and her competitors would whip out their cell phone calculators after a round to add up their scores… for 9 holes!

Apply for a Leadership Position on NSTA's Board and Council

By Lauren Jonas, NSTA Assistant Executive Director

Posted on 2013-09-06

Are you looking for a way to hone your leadership skills and give back to the science education community? Consider sharing your time and talents with the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) by applying for a nomination to the NSTA Board of Directors and Council. To learn more about what these prestigious Board and Council positions involve, please join our web seminar on September 17th; it will provide details about the open positions, offer strategies for submitting an effective application, and answer all your questions about the process. The free, interactive program begins at 6:30 p.m. eastern time. Get details on this web seminar and register.

Applications for the NSTA Board and Council are open through October 9th.

Board of Director offices to be filled in the 2014 election are:

- President – Term of office: 3-year commitment beginning June 2014 through May 2017(Year 1 as President-elect; Year 2 as President; Year 3 as Retiring President)

- Division Directors – Term of office: 3-year commitment beginning June 2014 through May 2017

- Multicultural/Equity in Science Education

- Preservice Teacher Preparation

- Research in Science Education

Council offices to be filled in the 2014 election are:

- District Directors – Term of office: 3-year commitment beginning June 2014 through May 2017

- District I – CT, MA, RI

- District VI – NC, SC, TN

- District VII – AR, LA, MS

- District XII – IL, IA, WI

- District XIII – NM, OK, TX

- District XVIII – Canada

Applications can be downloaded at http://www.nsta.org/nominations.

Are you looking for a way to hone your leadership skills and give back to the science education community? Consider sharing your time and talents with the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) by applying for a nomination to the NSTA Board of Directors and Council. To learn more about what these prestigious Board and Council positions involve, please join our web seminar on September 17th; it will provide details about the open positions, offer strategies for submitting an effective application, and answer all your questions about the process.

Engaging students in a variety of instructional strategies

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2013-09-05

What would implementing the NGSS “look like” in a classroom? Each of the featured articles in this issue highlights several classroom strategies that you can use to start making connections to the disciplinary core ideas, practices, and crosscutting concepts of the NGSS.

What would implementing the NGSS “look like” in a classroom? Each of the featured articles in this issue highlights several classroom strategies that you can use to start making connections to the disciplinary core ideas, practices, and crosscutting concepts of the NGSS.

If you teach K-5, be sure to read this month’s guest editorial The Next Generation Science Standards and the Common Core State Standards: Proposing a Happy Marriage. The author suggests ways in which these two documents complement each other and the provides several examples of the connections between science and literacy.

The moon is certainly the source of much folklore, legends…and misconceptions. The Moon Challenge* shows how the authors challenged misconceptions with patterns (moon phases), a research project, and trade books. When is the Next Full Moon? (Formative Assessment Probes)* uses the idea of a “concept cartoon” to probe student’s understanding. [SciLinks: Moon Phases]

Small Wonders-Close Encounters* shows strategies to introduce students to the world of digital microscopy. The authors share what to look for in a digital microscope and offer suggestions for differentiating the lesson for younger students, English language learners, and special education students. [See how to use a tablet as a digital microscope] The Science 101 column asks (and answers) How Does an Electron Microscope Work?* [SciLinks: Microscopes, Electron Microscope]

I heard a teacher lament that with the new standards, all of the fun activities will have to go. I hope she reads Desert Survivors* in which a puppet play based on the “Survivor” TV program teaches students about argumentation and desert habitats. Students had to research the desert environment to equip their contestants. [SciLinks: Desert] Young students are interested in animals and their homes. Habitable Homes (Teaching Through Trade Books)* has two 5e lesson plans (K-2 and 3-5) on habitats and biomes. [SciLinks: What is a Habitat? Adaptations of Animals, Habitats, Biomes, Habitats and Niches]

I was never very good at teacher-created bulletin boards. But word walls were different! Interactive Word Walls shows how to kick up the traditional word wall a few notches (in five steps) to make it truly a student project. The examples are wonderful! This might be more of a challenge for middle or high school levels, where the teacher meets 5-6 classes each day, but I’d be interested in how this could be implemented in these upper grades. Science vocabulary is also the theme of Science as a Second Language. The authors share several strategies for helping English language learners with science vocabulary, including foldables, DOTS charts, and U-C-ME graphic organizers, examples of which can be found in this issues Connections*.

The authors of What Does Culture Have to Do With Teaching Science?* share strategies for capitalizing on the cultural backgrounds students bring to the classroom. Using Hindu beliefs as an example, they show how students can make connections between cultural beliefs and scientific concepts. [SciLinks: How Do Plants Grow?] Food for Thought (The Early Years)* has lesson ideas for helping our youngest scientists find evidence of how animals use plants for food and shelter. [SciLinks: How Do Animals Help Plants, Plants as Food, What Are the Parts of a Plant?]

* Many of these articles have extensive resources to share, so check out the Connections for this issue. Even if the article does not quite fit with your lesson agenda, there are ideas for handouts, background information sheets, data sheets, rubrics, and other resources.

What would implementing the NGSS “look like” in a classroom? Each of the featured articles in this issue highlights several classroom strategies that you can use to start making connections to the disciplinary core ideas, practices, and crosscutting concepts of the NGSS.

What would implementing the NGSS “look like” in a classroom? Each of the featured articles in this issue highlights several classroom strategies that you can use to start making connections to the disciplinary core ideas, practices, and crosscutting concepts of the NGSS.

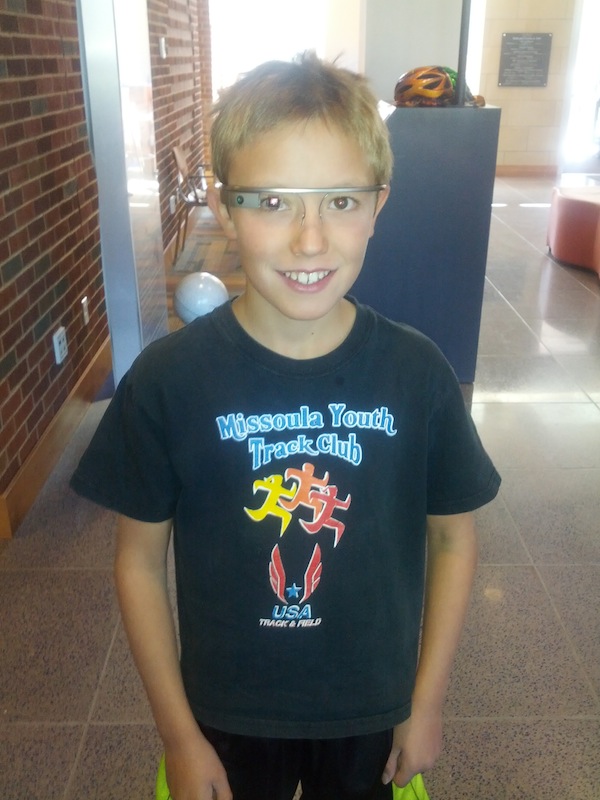

Google Glass: A Lab on the End of your Nose

By Martin Horejsi

Posted on 2013-09-05

Over the summer I had the privilege of watching a 5th grader take Google Glass for a spin. The student was far faster at mastering the interface than I was, and also much more creative in his application of Google Glass.

Google Glass is, well, I better let Wikipedia explain it:

Google Glass (styled “GLΛSS”) is a wearable computer with an optical head-mounted display (OHMD) that is being developed by Google in the Project Glass research and development project, with a mission of producing a mass-market ubiquitous computer. Google Glass displays information in a smartphone-like hands-free format that can communicate with the Internet via natural language voice commands

Or perhaps a video would help.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v1uyQZNg2vE[/youtube]

After a few minutes with Google Glass it became apparent that when Glass enters the education arena, especially the sciences, everything will be different. To have instant access to information via voice command, visual content and capture, mapping, and pretty much all the power of Google behind it, Glass will not only give us that third hand we could sure use in the lab and when doing field work, but also provide a level of communication and data capture in a natural way that easily exceeds our current standard practices.

As I watched the young student navigate the common uses for Glass, it was truly one of those rare magical moments when we don’t just glimpse the future, we are immersed in it! Glass is not just another accessory or device or even interface, although it certainly is all those, but it is also a true extension capabilities limited only by its wearer’s imagination.

Obvious uses for Glass will mimic those traditional tasks we currently use laptops, tablets, phones, cameras, and other stand-alone devices for. Using Glass for those tasks is just comfort food while our minds wrap around an entirely new dimension. Glass in education will not be more of the same. Glass will be more of everything at first, then quickly following will be a literal explosion in possibilities where we can recapture time by speeding tasks, amplifying capabilities by layering content in real time, and massively changing the precision of our information flow both in download and upload.

At first I wanted to see the young Glass user run it through its paces, but soon it was the long pauses where the student was deeply immersed in a virtual world glowing just a few centimeters in front of his eye that told the tale. Google Glass can take traditional instruction and personalize it, differentiate it, constructivise it, magnify it, amplify it, and leverage its virtual aspect to make the learning activities more real.

As much I wanted Glass right now, I had to temper my enthusiasm knowing that like most emergent technologies, the things we do today will seem mundane compared to what we will do a year from now. As an educator, I know tablets are a revolution. But Google Glass will be a paradigm shift. In other words, Glass changes everything.

Over the summer I had the privilege of watching a 5th grader take Google Glass for a spin. The student was far faster at mastering the interface than I was, and also much more creative in his application of Google Glass.

Uncovering Student Ideas in Science Workshops at NSTA’s Area Conferences This Fall

By Wendy Rubin, Managing Editor, NSTA Press

Posted on 2013-09-03

“Uncovering Student Ideas is highly recommended for teachers at every level; it contains a set of essential tools that cross discipline, grade, and ability levels. There’s no better way to guide your planning and decision-making process.”

“Uncovering Student Ideas is highly recommended for teachers at every level; it contains a set of essential tools that cross discipline, grade, and ability levels. There’s no better way to guide your planning and decision-making process.”

—from Juliana Texley’s review of Uncovering Student Ideas in Science, Vol. 4

Are you looking for ways to transform your instruction this school year? Learn how to do so while also supporting learning with preconference workshops at the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) fall conferences in Charlotte and Denver. Page Keeley, the author of the bestselling Uncovering Student Ideas in Science series, and coauthor Joyce Tugel will

- introduce participants to the use of formative assessment in science,

- help them understand the types of preconceptions students have and ways to surface and address them,

- practice strategies for questioning and monitoring student learning during different stages in a cycle of instruction,

- show participants how to develop assessments that probe students’ thinking, and

- demonstrate how to combine formative assessment classroom techniques (FACTs) with the eight scientific practices in the Next Generation Science Standards.

Both classroom and teacher learning applications will be addressed, so classroom teachers, science specialists, preservice instructors, and more will benefit from this daylong workshop. All participants will receive a copy of Uncovering Student Ideas in Science, Vol. 4: 25 New Formative Assessment Probes.

More information and registration details can be found here:

- Charlotte: www.nsta.org/charlotteassessment

- Denver (with coauthor Joyce Tugel): www.nsta.org/denverassessment