Making the Most of Class Time

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2016-10-31

At the beginning of class, it takes my students a long time to settle down. We are wasting time as I try to get their attention. Any suggestions? –T., Maryland

At the beginning of class, it takes my students a long time to settle down. We are wasting time as I try to get their attention. Any suggestions? –T., Maryland

To take advantage of the class time we have, it helps to have an established routine so students know what to do when they come into the classroom.

One method I found effective was posting an agenda. When the students entered the lab, they saw what the learning goals were, what activities they were going to work on in class, what needed to be turned in, and what materials they needed (pencil, science notebook, paper, and so on). As they assembled these materials and put their other things away, they still had a little time to socialize, which is important to middle schoolers. When we started the lesson or lab investigation, they had their materials in order.

Another suggestion is to have a warm-up or bellringer activity. Students should get started right away, even before the bell actually rings. The students are focused while you take attendance, distribute materials, or return assignments. Some examples include

- Answer a question about yesterday’s work or another related topic

- Respond to a statement or visual to uncover misconceptions or activate prior knowledge

- Complete a vocabulary entry with a graphic organizer

- Do a “quick write” with several sentences on a theme or topic

- Do a “quick draw” on a theme or topic

You can tell the students to quiet down over and over every day. Or you can help students take responsibility for using time purposefully through guidance and modeling (and persistence).

At the beginning of class, it takes my students a long time to settle down. We are wasting time as I try to get their attention. Any suggestions? –T., Maryland

At the beginning of class, it takes my students a long time to settle down. We are wasting time as I try to get their attention. Any suggestions? –T., Maryland

Just as its subtitle says, this important book aims to reshape your approach to teaching and your students’ way of learning.

Just as its subtitle says, this important book aims to reshape your approach to teaching and your students’ way of learning.

Time for science?

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2016-10-30

When I was student teaching, I had some really good science lessons for second-graders that lasted about an hour. But now I have only a half-hour for science each day. I need suggestions for shorter lessons. – C., Colorado

When I was student teaching, I had some really good science lessons for second-graders that lasted about an hour. But now I have only a half-hour for science each day. I need suggestions for shorter lessons. – C., Colorado

I’m glad to hear that your school schedules science daily. In many elementary schools, science and social studies have been deemphasized, in favor of reading and math.

- If your schedule is flexible enough, “borrow” time from another subject to complete the activity, making up the time later.

- Divide the activity into several parts, perhaps making observations or collecting data one day and doing the analysis or summarization later. (You may have to include time to review on the second day)

- Use time during writing instruction for students to summarize the lesson in their science notebooks.

- Use nonfiction books on the topic during reading instruction, read-alouds, or personal reading to provide background prior to or after the science lesson.

Each month, NSTA’s Science & Children publishes features to help educators craft additional age-appropriate lessons:

- Teaching with Trade Books explores a concept with recommended books and lessons. For example, the September 2016 topic is “What We Do With Ideas.”

- The Early Years features easy-to-use ideas for developing student interest and curiosity. The July 2016 topic is “Discovering Through Deconstruction.”

- Articles related to the monthly theme include lesson plans, connections to the Next Generation Science Standards, and related materials.

Even at the secondary level, the class period is often not long enough to complete an investigation or activity. And I’ve never heard science teachers say they had too much time!

Photo: https://www.flickr.com/photos/cgc/7080721/sizes/q/

Tackling Scientific Problems and Pitching Engineering Solutions at #NSTA16 Columbus

By Lauren Jonas, NSTA Assistant Executive Director

Posted on 2016-10-29

This December, the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) will feature a special strand “Tackling Scientific Problems and Pitching Engineering Solutions” at our 2016 Area Conference on Science Education, in Columbus, Ohio, December 3-5. We need this strand, because the challenges facing society are both complex and interdisciplinary. Issues like water availability/quality, climate change, renewable energies, food shortages, the need for improved transportation/city infrastructure, and issues in the biomedical realm require clearly defining problems that can be solved through design. Students address these issues by implementing the practices of scientists and engineers, including developing explanations, designing and building models, and creating solutions. Students must be able to link the domains of science and teachers must teach students in a learnable manner that reaches multiple grade levels, increasing in depth and sophistication.

The featured presentation for this strand will be “Sowing the Seeds of STEM,” on Friday, December 2, from 12:30 PM – 1:30 PM at the Greater Columbus Convention Center, B130. Presenter Kimberly Clavin (Pillar Technology: Columbus, OH) tells us that today’s world delivers advanced technologies at lightning speeds—and with that comes an exponential growth in STEM fields. How can educators prepare middle school and high school students without a background in the emerging fields? Learn various strategies to attract and grow a diverse range of students into these in-demand career fields.

The featured presentation for this strand will be “Sowing the Seeds of STEM,” on Friday, December 2, from 12:30 PM – 1:30 PM at the Greater Columbus Convention Center, B130. Presenter Kimberly Clavin (Pillar Technology: Columbus, OH) tells us that today’s world delivers advanced technologies at lightning speeds—and with that comes an exponential growth in STEM fields. How can educators prepare middle school and high school students without a background in the emerging fields? Learn various strategies to attract and grow a diverse range of students into these in-demand career fields.

Below is a small sampling of other sessions on this topic:

- Human-Centered Engineering Design: The Key to STEM

- Developing Scientific Arguments: Claims and Stories in the Graphs

- Learning Ecosystem Management with NGSS: Developing Solutions to Invasive Species Using Science and Engineering Practices

- EiE Ohio: Building 21st-Century STEAM Learners

- Impactful Learning: Engineering to Serve Special Needs Students—The Win-Win Scenario

- Teaching Engineering in Grades K–3

Want more? Browse the program preview, or check out more sessions and other events with the Columbus Session Browser/Personal Scheduler. Follow all our conference tweets using #NSTA16, and if you tweet, please feel free to tag us @NSTA so we see it!

Want more? Browse the program preview, or check out more sessions and other events with the Columbus Session Browser/Personal Scheduler. Follow all our conference tweets using #NSTA16, and if you tweet, please feel free to tag us @NSTA so we see it!

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2017 National Conference

2017 STEM Forum & Expo

Follow NSTA

Only at NSTA Minneapolis: #ToysForNerds

By Lauren Jonas, NSTA Assistant Executive Director

Posted on 2016-10-29

Uh oh, someone hold me back #toysfornerds #ONLYatNSTA pic.twitter.com/AdKmAvsfjE

— Sara Kobilka (@SaraKDM) October 28, 2016

"A zombie got my leg" #STEM challenge to create a prosthetic leg #nsta2016 #nsta16 @TeachNgineering pic.twitter.com/EP5JGQzr5r

— Matt Nupen (@mattnupen) October 29, 2016

#ONLYatNSTA I DO love being a science teacher! pic.twitter.com/YQf6Bp74eT

— Stephanie Francis (@tagteacher2002) October 27, 2016

#scienceteachers change the world one “Why?” at a time! @ainissaramirez tells us how #OnlyAtNSTA pic.twitter.com/jQteaj5OVz

— Lauren Jonas (@LaurenE_Jonas) October 27, 2016

@SPPS_Science @SPPS_News Jim Schrankler being recognized as a Presidential Award Finalist at MNSTA #OnlyAtNSTA pic.twitter.com/TKhnu8PTpY

— Sarah Bosch (@sbosch_spps) October 27, 2016

#ONLYatNSTA pic.twitter.com/HgTSQXp8w3

— NatSciTeachAssoc (@NSTA) October 29, 2016

SMHS in da house!#onlyatnsta#sciencerocks pic.twitter.com/yojxhIgA0z

— Dawn Paurus (@dawn_paurus) October 28, 2016

#nsta16 what’s more fun than teaching science??!! Learning to teach science with all your fav science teachers! #knightnation pic.twitter.com/bPNRL9FYrn

— Ms. Volkmann (@ScienceMsV) October 28, 2016

That time you happened on forensic clues on your way to an #NSTA16 session. #OnlyAtNSTA pic.twitter.com/0CWZLE66Xr

— Claire Reinburg (@C_Reinburg) October 27, 2016

Prism glasses and a light show. #onlyatnsta @KatieAEnglund @Shellygilson1 pic.twitter.com/SpXmdDAywm

— Courtney Qualley (@QualleyCourtney) October 28, 2016

#OnlyAtNSTA Can I play with clay and learn science! pic.twitter.com/3LOozv9fmL

— Barbara Wendt (@WendtScience) October 28, 2016

#onlyatnsta Prof. Tubesing lights up ASEE engineering day!! pic.twitter.com/gxGwtBgUao

— Deb Besser (@Deb_Besser) October 28, 2016

Day 2 of the science teachers conference in Minneapolis #NSTA #OnlyAtNSTA #NSTA16 pic.twitter.com/4v8SdxvoVo

— Beth Hamilton (@deafsciencebeth) October 28, 2016

Kazoo engineering expert #carolinaredcarpet #OnlyAtNSTA pic.twitter.com/F1gqWvtXMM

— Sara Kobilka (@SaraKDM) October 28, 2016

New & old STEM Forum members collaborate as we plan out 2017 STEM Forum. Good times and plans #NSTA16 #OnlyAtNSTA pic.twitter.com/nU2NdyAdfO

— Jennifer Williams (@ScienceJennifer) October 27, 2016

Red kneed tarantula #ONLYatNSTA pic.twitter.com/sK829MXmYC

— tim ronhovde (@mctreehugger) October 28, 2016

Welcome to Twitter! #OnlyAtNSTA https://t.co/0okZgDSnLD

— Sarah Bosch (@sbosch_spps) October 28, 2016

#OnlyAtNSTA @ZWSTEAMRoller @mikesavage1 pic.twitter.com/GIcXRW2OeQ

— Sara Welu (@Sdub1078) October 28, 2016

Reverse engineering a kazoo. Let’s get destructive!! How can I break this? The dark side is so tempting and encouraged! #OnlyAtNSTA pic.twitter.com/GAoxEDvxnF

— Sara Kobilka (@SaraKDM) October 28, 2016

In a highly unscientific survey it has been decided that the cutest dog in the world is #ONLYatNSTA pic.twitter.com/mXak7gZGJm

— NatSciTeachAssoc (@NSTA) October 6, 2016

Reverse engineering a kazoo. Let’s get destructive!! How can I break this? The dark side is so tempting and encouraged! #OnlyAtNSTA pic.twitter.com/GAoxEDvxnF

— Sara Kobilka (@SaraKDM) October 28, 2016

Won $50 at the door prize at the first session ! #onlyatNSTA Thanks #vernier ! #STEM #scied #NSTA pic.twitter.com/VmanbeSNIv

— Kim Nesvik (@knesvik1) October 28, 2016

Learning to use google forms for assessment from @kamelgaard at #NSTA16 #NSTA2016 #OnlyAtNSTA pic.twitter.com/cipuYLZGkw

— Matt Nupen (@mattnupen) October 28, 2016

MVPS Science teachers at NSTA in Mlps. Great day of professional learning. #mvteachers #mvpsrocks pic.twitter.com/BCoRRNabD5

— MV Curriculum (@MV_CIA) October 27, 2016

I want this!!! Saw this atomic model at the exhibit @FreyScientific #NSTA16 #NSTA #OnlyAtNSTA pic.twitter.com/BcArsvYY2Q

— Beth Hamilton (@deafsciencebeth) October 28, 2016

Happy to be with family in Minneapolis. #onlyatNSTA #NSTA16 @NSTA# @bflyguy @JeanTushie pic.twitter.com/vkknC0rAxE

— Christine Anne Royce (@caroyce) October 27, 2016

Designing on a seriously deficit budget #onlyatnsta pic.twitter.com/u0b7uRk4Ox

— Rhonda Fode (@CoachFode) October 27, 2016

…and then I won $75 to use on my class!!!#OnlyatNSTA pic.twitter.com/MnYn837y7M

— Courtney Qualley (@QualleyCourtney) October 27, 2016

Conference exp part 1: why yes TSA they are children’s books & 150 paper helicopters. I’m a science teacher #onlyatNSTA @nsta #NSTA16

— Christine Anne Royce (@caroyce) October 26, 2016

We are looking good #ONLYatNSTA pic.twitter.com/wAQK5rwomx

— Jodi Peterson (@stemedadvocate) October 28, 2016

Won a Starbucks gift card for creating the loudest kazoo! Me, loud, who’d have thunk it?!? #engineeringwinner #STEAM #OnlyAtNSTA pic.twitter.com/CEjgrxNsHz

— Sara Kobilka (@SaraKDM) October 28, 2016

Hanging out with Joe Mauer at NSTA. #ONLYatNSTA #NSTA2016 pic.twitter.com/JrnKpINiZn

— Scot Johnson (@scotjohn30) October 28, 2016

Great PD!!! #OnlyAtNSTA pic.twitter.com/Pi3mP77BiT

— Jacey Brown (@brown_ja3) October 28, 2016

#OnlyAtNSTA Can I read a science paper from 1953 on DNA, and build what they discovered with pool noodles, magnets, and 3D printers-😁 pic.twitter.com/HpJjO4vvKc

— Barbara Wendt (@WendtScience) October 28, 2016

Thank you Victor Sampson for leading a great un-conference discussions on argument-driven inquiry. #ONLYatNSTA @nsta pic.twitter.com/JZVWYbeIXS

— Kim Stilwell (@KimStilwellNSTA) October 28, 2016

Met my #sciencesuperhero and got some smart advice today. THANK YOU @ainissaramirez pic.twitter.com/mDBgIliNZu

— Lauren Jonas (@LaurenE_Jonas) October 28, 2016

Hands on digestion #onlyatnsta pic.twitter.com/8w9F0O8Dyr

— Rhonda Fode (@CoachFode) October 27, 2016

Gotta love a hands-on engineering session where cheers erupt throughout the design process. #ONLYatNSTA pic.twitter.com/5cjEoFAuPR

— Sara Kobilka (@SaraKDM) October 28, 2016

When the presenter happens to use a book you wrote in her session. #surprise! #OnlyatNSTA #NSTA16 #NGSS #ece #STEMed @charlesbridge pic.twitter.com/XITOA4gPAt

— Ruth Spiro (@RuthSpiro) October 28, 2016

A great start to the NSTA area conference #ONLYatNSTA And a big thank you to NSTA and MN’s local planning team pic.twitter.com/bZvjwnRGQt

— Steve Walvig (@SteveWalvig) October 27, 2016

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

2016 Area Conferences

2017 National Conference

2017 STEM Forum & Expo

Follow NSTA

Bring More Everyday Engineering into your classroom

By Carole Hayward

Posted on 2016-10-28

A new book by NSTA Press helps middle school teachers incorporate engineering into their science classrooms.

More Everyday Engineering: Putting the E in STEM Teaching and Learning is a follow-up volume to 2012’s Everyday Engineering. The book is based on the “Everyday Engineering” column in NSTA’s middle school journal Science Scope and captures how engineering is required to make items from ice cubes to bandages. Authors Richard H. Moyer and Susan A. Everett do an excellent job at providing lessons that illustrate how “engineering is the process we use to develop solutions to the problems humans face.”

More Everyday Engineering: Putting the E in STEM Teaching and Learning is a follow-up volume to 2012’s Everyday Engineering. The book is based on the “Everyday Engineering” column in NSTA’s middle school journal Science Scope and captures how engineering is required to make items from ice cubes to bandages. Authors Richard H. Moyer and Susan A. Everett do an excellent job at providing lessons that illustrate how “engineering is the process we use to develop solutions to the problems humans face.”

The activities are designed to give students an in-depth understanding of three different aspects of engineering—designing and building; reverse engineering to learn how something works; and constructing and testing models. Moyer and Everett use the 5E learning-cycle format in each activity and focus on items that students are familiar with such as sunglasses and speakers and earbuds.

Chapter 4, “An In-depth Look at 3-D,” is particularly relevant to middle school students who have grown up surrounded by the latest 3-D technology in video games, televisions, and movies. The activity worksheet in that chapter focuses on vision and perception as a means to investigating 3-D. Each of the chapters in the book provide helpful teacher background information, historical context, a materials list, and safety information.

The Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) stress the importance of incorporating engineering and technology into the science classroom. This book can help teachers connect science and engineering, and can serve as a useful tool for engineers leading outreach activities, leaders of after-school and summer enrichment programs, and parents. Most importantly, the book helps provide opportunities for students “to deepen their understanding of science by applying their developing scientific knowledge to the solution of practical problems” (see NGSS, Appendix A).

This book is also available as an e-book.

Fall for These Savings on NSTA Press Books!

Between now and November 1, 2016, save $15 off your order of $75 or more of NSTA Press books or e-books by entering promo code BKS16 at checkout in the online Science Store. Offer valid only on orders placed of NSTA Press books or e-books on the web and may not be combined with any other offer.

Follow NSTA

A new book by NSTA Press helps middle school teachers incorporate engineering into their science classrooms.

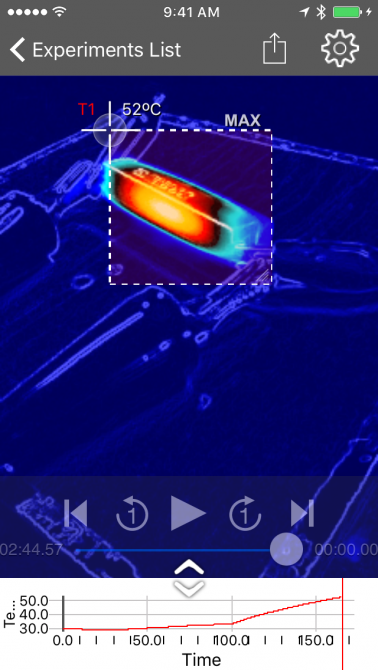

FLIR ONE Thermal Imaging Camera

By Edwin P. Christmann

Posted on 2016-10-27

Introduction

The imaginations of middle school and high school students will be fully engaged in the science classroom with the FLIR ONE Thermal Imaging Camera. This camera’s thermal capabilities allow students to explore things invisible to the human eye. For example, students can use the camera to investigate the world of thermodynamics in a manner that parallels the excitement and mystery evoked by sitting on the edge of your seat during a cutting-edge science fiction movie.

How does it work?

What we can see with naked eye is restricted to visible light. Therefore, when you consider the electromagnetic spectrum (EM), which encompasses radio waves, microwaves, infrared light, visible light, ultraviolet light, x-rays, and gamma rays, it becomes evident that what we can see with our eyes is limited. As an example, devices such as military night vision goggles make it possible to see images in the dark. In a similar way, the FLIR ONE Thermal Imaging Camera is a device for us to “see” beyond visible light.

Thermal-imaging cameras, like the FLIR ONE, can “see” heat signatures, which are converted to display variations of temperatures, e.g., How an icy soft drink contrasts with the flame on a candle. This is because all objects emit thermal energy and the hotter the object; the more energy given off by the object. The energy emitted is known as the “heat signature.” Hence, every object has a different heat signature; and it’s those signatures that are detected by thermal imagers like the FLIR ONE. Moreover, since thermal cameras are not concerned with visible light, regardless of lighting conditions, thermal cameras can detect the different heat signatures in a variety of situations. Therefore, images of temperature variations can be observed with this type of device.

FLIR ONE Thermal Imaging Camera Compatibility

The Thermal Camera is made for the iPhone and the iPad. It is very easy to use and, because no interface is needed, it is a snap to use in the classroom. Subsequently, teachers will have no problem having students connect the device for experiments. The first step, however, is load the free Vernier Thermal Analysis for FLIR ONE application, which is available for download on the iTunes App Store [https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/vernier-thermal-analysis-for/id1083139486?mt=8]. It requires iOS 9.0 or better and should be installed before connecting the camera to your device. The Vernier Thermal Analysis for FLIR ONE application is simple to access and takes only a few minutes to upload.

As explained in the iTunes store:

“Vernier Thermal Analysis for FLIR ONE allows you to mark up to four locations or regions on a thermal image. In a selected region, you can determine minimum, maximum, or average temperature. Graph temperature data live during an experiment, then export to our Graphical Analysis app for further analysis. Thermal image videos can also be exported to the Photos app.”

The Thermal Camera, in conjunction with the Thermal Analysis app, can do much more than simply detect heat. Students will also be able to record and graph live temperature data from up to four locations on an image. This will allow them to compare the temperature data between different locations during an experiment. Furthermore, each picture taken with this device will also simultaneously take a standard picture, providing greater detail of the image.

The FLIR ONE can be used across the science content areas (i.e., physics, chemistry, earth science, biology, etc.) and will definitely enhance the study of thermodynamics for students– especially for visual learners! Below are samples of links to ideas for classroom experiments:

Rubbing erasers, hands and ice: http://80.77.70.144/DocDownload/Assets/edu/T810113-en-US.pdf

Knife and wooden spoon: http://80.77.70.144/DocDownload/Assets/edu/T810111-en-US.pdf

Cups and clothes: http://80.77.70.144/DocDownload/Assets/edu/T810109-en-US.pdf

Conclusion

The FLIR ONE Thermal Camera is a new technology application that engages students into meaningful and exciting inquiry-based learning! Undoubtedly, this user-friendly device has a kaleidoscope of meaningful uses for 21st Century science classrooms! There is little doubt that its use will spawn creativity and heighten the interest of thermodynamics content for students!

Equipment and Cost:

Cost: $249

http://www.flir.com/flirone/ios/

http://www.vernier.com/products/sensors/temperature-sensors/flirone-ios/

Edwin P. Christmann is a professor and chairman of the secondary education department and graduate coordinator of the mathematics and science teaching program at Slippery Rock University in Slippery Rock, Pennsylvania. Anthony Balos is a graduate student and a research assistant in the secondary education program at Slippery Rock University in Slippery Rock, Pennsylvania.

Introduction

The imaginations of middle school and high school students will be fully engaged in the science classroom with the FLIR ONE Thermal Imaging Camera. This camera’s thermal capabilities allow students to explore things invisible to the human eye. For example, students can use the camera to investigate the world of thermodynamics in a manner that parallels the excitement and mystery evoked by sitting on the edge of your seat during a cutting-edge science fiction movie.

Working cooperatively

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2016-10-26

I’m frustrated by my sixth graders. When they’re supposed to be working cooperatively, they are unfocused—it seems more like a social event. By middle school, shouldn’t students know how to work cooperatively? Or are they too immature? – G., Virgina

I’m frustrated by my sixth graders. When they’re supposed to be working cooperatively, they are unfocused—it seems more like a social event. By middle school, shouldn’t students know how to work cooperatively? Or are they too immature? – G., Virgina

Immaturity is not an excuse. I’ve seen wonderful cooperative learning taking place in kindergarten classes, with teacher guidance, modeling, and monitoring.

One might assume students have specific skill sets and experiences, but I’ve learned never to take anything for granted. If the students attended different elementary schools, their science backgrounds and the emphasis schools placed on science investigations will vary. You may have to teach (or remind) students what cooperative learning in science looks like.

Defining roles is a key component. Common roles in middle level science labs include group leader, presenter, data recorder, measurer, equipment manager, liaison/questioner, artist/illustrator, online researcher, timekeeper, and notetaker. Depending on the size of the groups, some roles can be combined.

It may help to have students define the roles, giving them ownership in the process. Ask, “What would a data recorder do?” (Students must answer without using the words data or recorder.) You can add suggestions, especially on safety. Job descriptions could be shared as posters, student-created videos, or put into students’ notebooks. Rotate roles periodically so all students have a chance to experience each one.

If some students lack polished interpersonal skills, start with brief, structured activities. Model cooperative behaviors and share examples of appropriate (and inappropriate) language.

To keep the groups focused and on-task, be sure students understand the purpose and the learning goals for the project or investigation and monitor them as they work.

Middle schoolers are capable of working cooperatively, and their enthusiasm is a bonus!

Photo: https://www.flickr.com/photos/xevivarela/4610711363/sizes/o/in/photostream/

I’m frustrated by my sixth graders. When they’re supposed to be working cooperatively, they are unfocused—it seems more like a social event. By middle school, shouldn’t students know how to work cooperatively? Or are they too immature? – G., Virgina

I’m frustrated by my sixth graders. When they’re supposed to be working cooperatively, they are unfocused—it seems more like a social event. By middle school, shouldn’t students know how to work cooperatively? Or are they too immature? – G., Virgina

Immaturity is not an excuse. I’ve seen wonderful cooperative learning taking place in kindergarten classes, with teacher guidance, modeling, and monitoring.

Join the National Day of Action for Full Funding of ESSA Student Success

By Jodi Peterson

Posted on 2016-10-24

Science educators, teacher leaders, and others in the STEM education community are encouraged to join thousands of K-12 educators, counselors, technology specialists, and librarians on October 26 for the national “Day of Action” to urge Congress to fully fund the flexible block grant (Student Support and Academic Enrichment Title IV, Part A) recently authorized in the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

The Student Support and Academic Enrichment (SSAE) block grant is designed to ensure that high needs districts have access to programs that foster safe and healthy students, provide students with a well-rounded education, and increase the effective use of technology in our nation’s schools.

Districts can choose to spend their Title IV/A dollars to improve instruction and student engagement in STEM by:

- Expanding high-quality STEM courses;

- Increasing access to STEM for underserved and at risk student populations;

- Supporting the participation of students in STEM nonprofit competitions (such as robotics, science research, invention, mathematics, computer science, and technology competitions);

- Providing hands-on learning opportunities in STEM;

- Integrating other academic subjects, including the arts, into STEM subject programs;

- Creating or enhancing STEM specialty schools;

- Integrating classroom based and afterschool and informal STEM instruction; and

- Expanding environmental education.

Advocates are trying to drive the highest possible funding level for the program, and are asking their members to call on lawmakers to fully fund this program.

Send a pre-written letter to your Member of Congress via the STEM Education Coalition Congressional Action Center

Call or email the Member’s office and ask to speak to the legislative assistant who handles appropriations issues. Call the Capitol Hill switchboard at (202) 224-3121 and ask to be connected to your member of Congress. If the legislative assistant is not in, you can leave a voicemail with your request. A sample script can be found here.

Send a tweet to your members of Congress.

Read the press release on the Title IV/A National Day of Action here.

It is important we get as many teachers as possible to contact their member of Congress. This is the first year for this grant program so it is critical that Congress appropriates a robust level of funding. Questions? Email me at jpeterson@nsta.org.

ED Releases Guidance on Title IVA Programs

The U.S. Department of Education has released its guidance document on Title IV,A Student Support and Academic Enrichment Grant (mentioned above). The guidance provides key information on the provisions of the new SSAE program including a discussion of the allowable uses of funds, role of the SEA, fiscal responsibilities, and the local application requirements. Read more here.

Sign the STEM Education Coalition letter to State Stakeholders on ESSA Implementation

The STEM Education Coalition is circulating a letter among the STEM education community asking stakeholders and interested organizations to join onto a sign-on letter that calls for state and local policymakers to prioritize STEM as they put together plans to implement the Every Student Succeeds Act. View the letter here; if your organization would like to sign on, please contact Lindsey Gardner of the Coalition at lgardner@stemedcoalition.org with your organization’s name and contact info. The deadline to sign on is Friday, November 4.

Jodi Peterson is Assistant Executive Director of Legislative Affairs for the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) and Chair of the STEM Education Coalition. e-mail Peterson at jpeterson@nsta.org; follow her on Twitter at @stemedadvocate.

Follow NSTA

Best STEM Books for K-12: List Coming Soon from NSTA

By Guest Blogger

Posted on 2016-10-22

Over the last few years, members of the teaching community have asked for a list of books containing the best STEM content for K–12. So we’re thrilled to be working on that now and to be able to invite readers to join us in late November, when we announce the list. Please bookmark this site (Best STEM Books for K–12), and follow NSTA on Twitter or Facebook to see if your favorite books make the list.

From METS to STEM

When an acronym becomes so common that users forget its origins, it can take on a life of its own. That’s what’s happened to STEM. The integration of mathematics, engineering, technology, and science began as a model (“METS”) in grant funding. From a basket category for college and career, STEM has now become a model for education from early childhood onward.

But the journey from a paradigm to implementation has proved challenging in school settings. In many schools “silos” still exist; Teachers of each discipline form a community of learning and cooperate in their ideas, but often the ways of knowing in each discipline remain.

STEM is more than a concept diagram with connections among four (or more) subject areas. It’s a unique way of knowing and exploring the world. The STEM approach involves the essence of the practices of science and engineering. Tools like mathematics, technology, and communication skills are interwoven in STEM explorations. That seamlessness is what challenges educators around the world.

Nowhere is that more obvious than when teachers look to find literature to integrate into a STEM curriculum. NSTA has worked with the Children’s Book Council for 45 years to identify Outstanding Science Trade Books. Often in their annotations the reviewers have indicated the winners were great for STEM curricula.

But are they really STEM? Experts, including the NSTA Board, were interested in the question. The first draft of a new set of criteria came from J. Carrie Launius at the University of Missouri. In her research, Launius proposed that redefining the STEM literature genre would not only improve teachers’ understanding of the approach but would raise the level of understanding among students.

To represent the philosophy of STEM, NSTA invited a unique collaboration with three other groups, the American Association of Engineering Educators, the International Technology and Engineering Educators Association, and the mathematics reps from Society of Elementary Presidential Awardees. Through almost a year of study, the group came up with these criteria for the best STEM literature for young readers:

STEM Superlatives

The best books would invite STEM‐like thinking by

- Modeling real‐world innovation

- Embracing real‐world design, invention and innovation

- Connecting with authentic experiences

- Showing assimilation of new ideas

- Illustrating teamwork, diverse skills, creativity, and cooperation

- Inviting divergent thinking and doing

- Integrating interdisciplinary and creative approaches

- Exploring multiple solutions to problems

- Addressing connections between STEM disciplines

- Exploring Engineering Habits of Mind

- Systems thinking

- Creativity

- Optimization

- Collaboration

STEM in Practice

The best STEM books might represent the practices of science and engineering by:

- Asking questions, solving problems, designing and redesigning

- Integrating STEM disciplines

- Showing the progressive changes that characterize invention and/or engineering by

- Demonstrating designing or redesigning, improving, building, or repairing a product or idea

- Showing the process of working through trial and error

- Progressively developing better engineering solutions

- Analyzing efforts and makes necessary modifications along the way

- Illustrates at points, failure might happen and that is acceptable providing reflection and learning occurs.

- Communication

- Ethical considerations

Challenging criteria, to be sure. What might be most startling is what they don’t include: specific requirements for extensive content in any of the individual subject areas. This was a subject of extensive discussion by the group. In the end, they decided that while a great integrated STEM book might have a lot of content, a book might represent the best STEM attitudes and practices an be just plain “inviting.”

Next, the Children’s Book Council took over, contacting dozens of publishers to let them know the effort was underway. And the results: Astounding! While in most years about 150 books are submitted for Outstanding Science Trade Books, the first solicitation for Best STEM Books drew more than double that many.

But of course, it was a new process and a new vision. Among the entries were many really great books about science, some new approaches to mathematics and some fascinating engineering stories. But were they STEM? Did they tell? Or invite?

Months of reading and rich discussions ensued. Books were read, rated and re-examined. Judges struggled to separate the content of the books from the ways that creative STEM teachers could use them.

What Will Make the List?

But in the end, the process worked. The collaboration among teachers from different backgrounds proved that STEM works—in all sorts of problem-solving situations.

The result is a list of BEST STEM books that the associations hope will help influence not just publishing but education at all levels. The field is blooming!

So the Associations and their representatives invite you to enjoy the first list of the best STEM literature—coming in November. We can’t wait to share!

2016 Selection Committee

Juliana Texley, NSTA Past President; Carrie Launius, NSTA District XI Director, Retired K-12 Classroom Teacher, St. Louis, MO; Christine Royce, Professor, Department of Teacher Education, Shippensburg University; Pamela S. Lottero-Perdue, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Science Education, Director, Integrated STEM Instructional Leadership (PreK-6) Post-Baccalaureate Program, Department of Physics, Astronomy & Geosciences, Towson University, Chair, Pre-College Engineering Education Division, American Society for Engineering Education; Peggy Carlisle, Gifted Education Teacher, Pecan Park Elementary School, Jackson, MS; Sharon Brusic, Professor & Coordinator for Technology & Engineering Education, Dept. of Applied Engineering, Safety & Technology, Millersville University of Pennsylvania, Millersville, PA; Suzanne Flynn, Professor, Lesley University/Cambridge College, Fort Myers, FL; Thomas Roberts, VP of Programming for ITEEA Children’s Council, Doctoral Candidate in STEM Education at the University of Kentucky; Kathy Renfrew, Proficiency Based Learning Team, Science Specialist, Agency of Education , Barre, VT; Diana Ibarra, Shuyuan Science and Sustainability Programs Manager, The Independent Schools Foundation Academy, Hong Kong.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

2016 Area Conferences

National Conferences

- Los Angeles, California: March 30–April 2, 2017

- Atlanta, Georgia: March 15–18, 2018

- St. Louis, Missouri: April 11–14, 2019

- Boston, Massachusetts: March 26–29, 2020

- Chicago, Illinois: April 8–11, 2021

Follow NSTA