The Celestron Micro-Fi Wireless Digital Microscope: A Handful of Wow!

By Martin Horejsi

Posted on 2017-02-08

The term “wireless” does not so much describe what is, but instead what isn’t. And what isn’t is wires. What’s strange about many wireless technologies is there was never a wired version to begin with so describing the device by an absent feature that never was present in the first place can be confusing to those who grew up in a post-wire world. Imagine if cars were still considered horseless carriages. Another indication of progress is the lack of a capitol letter or hyphen. For example, email officially became a thing when it changed from E-mail to e-mail, and finally to email. And the internet arrived when it no longer was capitalized in common usage. At least that is one perspective on so-called disruptive technologies.

The Celestron Micro-Fi is a highly portable handheld digital microscope/video camera released in 2014 that can magnify subjects up to 80x. Powered by three AA batteries, and carrying onboard lighting in the form of six LEDs surrounding the lens, the Micro-Fi has few limits in the field.

The ergonomics of the Celestron Micro-Fi are excellent and make for a simple effective one-handed user interface. For tripod mounting a 1/4-20 threaded port is included that provides mechanical stability when needed when distance, safety or stealth is desired. The other controls include a illumination adjustment wheel, a focus wheel, a shutter release button, and an on/off switch.

Outdoors, lichen and moss present stunning subjects for the Celestron Micro-Fi. At the microscopic scale, there is no shortage of things at your fingertips to explore, including exploring your own fingertips.

Networking

The Celestron Micro-Fi uses the 802.11x standard of wireless communication to share images and video at 15 frames per second. The 802.11 standard is the one common to wireless network routers. Someday Bluetooth may be able to carry enough information to share video, but for now the wireless of choice is something else. Why this is important is three-fold. First, the 802.11 standard is powerful enough for the lightweight battery-powered unit to send video through the air up to 10 meters and up to two hours. Second, the wireless standard is not exclusive to one pairing. Instead the the Celestron Micro-Fi can have up to three individual computing devices connected at one time. And those devices can be of different operating systems and platforms such as an iPhone, an Android tablet and an iPad.

And third, because the selected network wireless on the device must be the Celestron Micro-Fi, there will be no wi-fi wireless internet connection while using the scope, cellular data connection is unaffected if one is available on the device. However when out in the field where there is no wi-fi network, the Celestron Micro-Fi works great and nothing is missing from the usual experience.

Eat Up!

Using the Celestron Micro-Fi App, (available on iOS and Google Play) the shutter button on the microscope captures an image onto all connected devices. I refer to this as “force feeding.” But also since the imagery is continuously viewable on all connected devices, the user of the tablet or phone can capture pictures at will. So a teacher or group leader using the Celestron Micro-Fi can force chosen images onto the devices ensuring all group members have the same base set of pictures. And the device users can supplement the forced set of images with their own picture choices taken by clicking a button in the App on the device.

Bird feathers at 80x are mesmerizing to explore. The patterns, textures, colors and iridescence is easily captured by the Celestron Micro-Fi. The transparent nose surrounding the lights and lens makes flush-focusing a snap. By literally setting the business-end of the Celestron Micro-Fi onto the subject and a bit of focus if needed, the wow just pours in. Even the youngest can use the Celestron Micro-Fi under basic-use conditions.

Museums and Zoos Everywhere

On one somewhat macabre field trip, I took the Celestron Micro-Fi out for a spin around my truck’s radiator grill. After a busy day driving through insect-rich highways, the grill was a veritable bug collection. Since the Celestron Micro-Fi has no onboard screen, the tablet must be nearby in order to focus the unit. Here is a collection of pictures taken with the Celestron Micro-Fi.

The term “wireless” does not so much describe what is, but instead what isn’t. And what isn’t is wires. What’s strange about many wireless technologies is there was never a wired version to begin with so describing the device by an absent feature that never was present in the first place can be confusing to those who grew up in a post-wire world. Imagine if cars were still considered horseless carriages. Another indication of progress is the lack of a capitol letter or hyphen. For example, email officially became a thing when it changed from E-mail to e-mail, and finally to email.

STEM Sims: Interactive Simulations for the STEM Classroom

By Edwin P. Christmann

Posted on 2017-02-06

Introduction

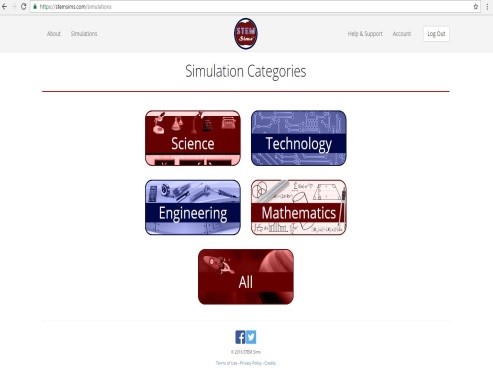

By subscribing to STEM Sims, teachers can open-up a kaleidoscope of educational and interactive classroom activities for students. These activities are relevant for teachers who are interested in a research-based approach to investigate STEM content that is aligned with the National NGSS Standards –https://stemsims.com/about/standards/national.pdf.

To begin, the first step is to visit the STEM Sims website, which can be found at the following website –https://stemsims.com. Once there, you will find that STEM Sims maintains over 100 simulations of laboratory experiments and engineering design simulations. Designed with excellent graphics, these simulations are meticulous in adhering to content and engaging students into meaningful classroom learning scenarios. Moreover, like the best video games, these simulations are challenging and are designed to harness students’ attention. The good news, however, is that the content of these activities is relevant and standards-based.

After sampling several activities, we found STEM Sims to be an incredibly user-friendly program for both teachers and students. Moreover, a single subscription gives access for 30 students to participate in the activities. In addition, for students who need remediation, STEM Sims provides students with background information and terminology for each simulation activity.

Another key feature for teachers is that each simulation includes lesson planning (often more than one), a video walkthrough, and an assessment with an answer key. Below are some examples:

Lesson Plan: https://stemsims.com/content/lessons/machines-lesson-1.pdf

Assessment (Answer Key): https://stemsims.com/content/teacher-guides/trench-dive-teacher.pdf

Conclusion

Aligned with the NGSS Standards, STEM Sims provides teachers with a motivational and an exciting approach for the teaching of hundreds of core STEM concepts. Moreover, with a wide-variety of authentic applications, STEM Sims makes it easy for the lessons to assimilate into various grade-levels and different courses, e.g., biology, chemistry, geology, etc. To substantiate its relevance, STEM Sims includes lesson plans, methods, and assessments for teachers to measure learning outcomes. If you are interested in having students experience these excellent scientific simulations, sign-up for a free trial. Undoubtedly, you will agree that STEM Sims offers students an excellent opportunity for scientific inquiry.

For a free trial, visit https://stemsims.com/account/sign-up

Recommended System Qualifications:

- Operating system: Windows XP or Mac OS X 10.7

- Browser: Chrome 40, Firefox 35, Internet Explorer 11, or Safari 7

- Java 7, Flash Player 13

Single classroom subscription: $169 for a 365-day subscription and includes access for 30 students.

Product Site: https://stemsims.com/

Edwin P. Christmann is a professor and chairman of the secondary education department and graduate coordinator of the mathematics and science teaching program at Slippery Rock University in Slippery Rock, Pennsylvania. Anthony Balos is a graduate student and a research assistant in the secondary education program at Slippery Rock University in Slippery Rock, Pennsylvania.

Introduction

Mentoring — A team effort

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2017-02-06

The most experienced science teacher is retiring this year at the middle school where I am principal. The other five teachers on the science faculty are early in their teaching careers. What are your thoughts on asking an experienced non-science teacher to mentor the new hire? —K., VA

The most experienced science teacher is retiring this year at the middle school where I am principal. The other five teachers on the science faculty are early in their teaching careers. What are your thoughts on asking an experienced non-science teacher to mentor the new hire? —K., VA

When I started as a teacher we did not have a formal mentor program, and the other two science teachers were almost as new as I was. I struggled with an especially challenging group of students until a veteran English teacher took me under her wing and helped me through the first year.

Years later, I was asked to mentor a new Spanish teacher. My knowledge of Spanish is minimal, but the principal noted many issues faced by new teachers transcend specific subjects. Classroom management, relationships with students, dealing with parents, navigating paperwork—all beginning teachers face these challenges. Even though our subjects were different, my mentee and I worked well together, developing a sense of trust and mutual respect.

In addition, perhaps the retiring teacher would be willing to be “on-call” to answer questions or provide advice. The district safety officer can also help with questions related to safe practices and inventories. Encourage your team of young science teachers to form a “support group” to share ideas and experiences.

The onsite mentor can help the new teacher with school culture and local issues and requirements, even though subject areas are different. Remind your new teacher that he/she has hundreds of potential online science mentors in the NSTA listservs and discussion forums. These experienced colleagues can provide just-in-time answers to questions specific to science instruction.

Having an onsite and online team of mentors can help to make the first year less lonely.

The most experienced science teacher is retiring this year at the middle school where I am principal. The other five teachers on the science faculty are early in their teaching careers. What are your thoughts on asking an experienced non-science teacher to mentor the new hire? —K., VA

The most experienced science teacher is retiring this year at the middle school where I am principal. The other five teachers on the science faculty are early in their teaching careers. What are your thoughts on asking an experienced non-science teacher to mentor the new hire? —K., VA

Commentary: It's About Time to Teach Evolution Forthrightly

By sstuckey

Posted on 2017-02-06

Fifty years ago, in 1967, the Tennessee legislature repealed the Butler Act, a 1925 law that made it a misdemeanor for a teacher in the state’s public schools to “teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals” (Larson 2012).

It was the Butler Act under which John Thomas Scopes was prosecuted and convicted in what remains the most iconic event in the litigious

history of evolution education in the United States (Moore and McComas 2016).

Teaching evolution is still contentious

The repeal of the Butler Act notwithstanding, the teaching of evolution is still contentious. Proposals to require the teaching of Biblical creationism, creation “science,” and intelligent design—all billed as scientifically respectable alternatives to evolution—have, in a series of federal court cases, been ruled to be unconstitutional (Branch, Scott, and Rosenau 2010). Evolution’s opponents have thus resorted to calling for teachers to be required or encouraged to misrepresent evolution as scientifically controversial. Such proposals were enacted as laws in Louisiana in 2008 and Tennessee in 2012 (Matzke 2016).

But of course evolution is anything but scientifically controversial. The nation’s premier scientific organizations, the National Academy of Sciences and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, are on record as describing evolution as the foundation of the biological sciences (NAS 2008; AAAS 2006). Moreover, the consensus is reflected among individual scientists. In a 2014 survey, 98% of scientists—and 99% of active research scientists and working PhD biomedical scientists—accepted that “[h]umans and other living things have evolved over time” (Rainie and Funk 2015).

Recognizing the responsibility of science educators to respect the scientific consensus, the nation’s leading science education organizations endorse the teaching of evolution. The National Science Teachers Association, for example, “strongly supports the position that evolution is a major unifying concept in science and should be emphasized in K–12 science education curricula” (NSTA 2013). And the authors of science standards agree: The Next Generation Science Standards, for example, treat evolution as one of four disciplinary core ideas of the life sciences (NGSS Lead States 2013).

Yet it is regrettably common for teachers to bypass, balance, or belittle evolution. A rigorous national survey of public high school biology teachers conducted in 2007 revealed that only 28% taught evolutionary biology forthrightly, while 13% presented creationism as scientifically credible in their classrooms, and a whopping 60% were “cautious”—teaching evolution, but feeling unable, unwilling, or unprepared to do so in full accordance with the recommendations of scientific and science education experts (Berkman and Plutzer 2011).

Be part of the solution

As a reader of The Science Teacher—and of the February issue focused on evolution—you probably already present evolution to your students as a central, unifying, and established principle of biology. Moreover, you may be likely to keep current on the latest developments in the evolutionary sciences and in effective science pedagogy through professional journals, reliable online resources (such as Understanding Evolution), and in service trainings. So you are not part of the problem. But you can be part of the solution.

You can improve the effectiveness of your own teaching of evolution, by, for example, taking into account the distinctive obstacles to understanding evolution (see, e.g., Kampourakis 2014); taking notice of the history, complexity, and diversity of the reactions of faith traditions in the United States to evolution (see, e.g., Giberson and Yerxa 2002); and taking advantage of the burgeoning literature emphasizing the practical applicability and the human relevance of evolution (see, e.g., Mindell 2006; Pobiner 2012). But you should also look beyond your own classroom.

If any of your colleagues present creationism as scientifically credible in their classrooms, you can gently but firmly remind them of their professional and legal responsibilities as science educators and government employees. If any are among the cautious, you can inspire them to improve their scientific knowledge and pedagogical confidence, enabling them to teach evolution honestly, accurately, and confidently.

(That is also the goal of the National Center for Science Education’s new teacher network, NCSEteach.) And those who already present evolutionary biology forthrightly can help you with those projects.

Finally, you can become a public voice to defend the integrity of science education. In recent years, proposed state science standards have been criticized for their treatment of evolution in Alabama, Kansas, Iowa, Kentucky, and South Carolina, while in 2016 alone, legislative attempts to undermine the teaching of evolution arose in Florida, Idaho, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and South Dakota. Science educators have commendably resisted these assaults, but it is clear these assaults will continue, or even intensify, in 2017—and so will the imperative to resist them.

If you recognize the need to improve your classroom presentation of evolution, or to support colleagues who may feel unable, unwilling, or unprepared to teach evolution forthrightly, or to defend the teaching of evolution in the public schools, but you simply haven’t found the time to do so yet, remember what Scopes reportedly said—with no great degree of originality but doubtless with plenty of feeling—when Tennessee repealed the Butler Act, 42 years after his conviction: “Better late than never.”

Glenn Branch (branch@ncse.com) is deputy director of the National Center for Science Education in Oakland, California.

References

American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). 2006. Statement on the teaching of evolution. http://bit.ly/AAAS-evolution

Berkman, M.B., and E. Plutzer. 2011. Defeating creationism in the courtroom, but not in the classroom. Science 331: 404–405.

Branch, G., E.C. Scott, and J. Rosenau. 2010. Dispatches from the evolution wars: Shifting tactics and expanding battlefields. Annual Reviews of Genomics and Human Genetics 11: 317–338.

Giberson, K.W., and D.A. Yerxa. 2002. Species of origins: America’s search for a creation story. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Kampourakis, K. 2014. Understanding evolution. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Larson, E.J. 2012. Creationism in the classroom: Cases, statutes, and commentary. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing.

Matzke, N.J. 2016. The evolution of antievolution policies after Kitzmiller v. Dover. Science 351: 28–30.

Mindell, D.P. 2006. The evolving world. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Moore, R., and W.F. McComas. 2016. The Scopes Monkey Trial. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing.

National Academy of Sciences (NAS). 2008. Science, evolution, and creationism. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

National Science Teachers Association (NSTA). 2013. NSTA position statement: The teaching of evolution. www.nsta.org/docs/PositionStatement_Evolution.pdf

NGSS Lead States. 2013. Next Generation Science Standards: For states, by states. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Pobiner, B.L. 2012. Use human examples to teach evolution. The American Biology Teacher 74 (2): 71–72.

Rainie, L., and C. Funk. 2015. Elaborating on the views of AAAS scientists, issue by issue. http://pewrsr.ch/2gETWcD

Editor’s Note

This article was originally published in the February 2017 issue of The  Science Teacher journal from the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA).

Science Teacher journal from the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA).

Get Involved With NSTA!

Join NSTA today and receive The Science Teacher,

the peer-reviewed journal just for high school teachers; to write for the journal, see our Author Guidelines, Call for Papers, and annotated sample manuscript; connect on the high school level science teaching list (members can sign up on the list server); or consider joining your peers at future NSTA conferences.

Fifty years ago, in 1967, the Tennessee legislature repealed the Butler Act, a 1925 law that made it a misdemeanor for a teacher in the state’s public schools to “teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals” (Larson 2012).

Students Teaching Science to Younger Students

By Debra Shapiro

Posted on 2017-02-04

A Science Ambassador from North Forsyth High School in Cumming, Georgia, uses a tube with a marble inside it as a “roller coaster” to teach an elementary school student about gravity, force, and motion.

For more than 42 years, Manhattan High School in Manhattan, Kansas, has offered the Wide Horizons Nature Program, a science course in which high school students “work with a partner to put together a [30-minute] educational program [and] teach [it] at local elementary [schools] and preschools,” says science teacher Leslie Campbell, who has taught it for five years. Wide Horizons students “report to my classroom to pick up supplies, then drive out to the schools to present. The goal is to do it all within a normal class hour,” Campbell explains.

“It has grown to be two classes per day (36 students enrolled between the two this year). They present 2–3 times per week on their subject,” she reports, adding, “I make sure their science instruction will enhance elementary school classes.”

The course has no set curriculum. In 1974, biology teacher Gary Ward designed it “as a flexible course for juniors and seniors to pursue their [individual] nature study interests,” says retired biology teacher Tish Simpson, who taught Wide Horizons from 1994 to 2011. Prerequisites include teacher recommendation, science interest, commitment to a year-long class, good character, reliability, and responsibility—“not necessarily their academic performance,” she notes. Students need to have completed required lab science credits or “be taking them simultaneously” because Wide Horizons is an elective, she adds. They also need to have “some form of transportation to the elementary schools.”

Campbell also relies on student recommendations because peers typically are knowledgeable about students’ attitudes and social skills when “dealing with younger students, teachers, and administrators,” she relates. After checking with guidance counselors and other teachers, she issues invitations to students interested in taking the course.

Students choose presentation topics based on their interests, with the caveat that the topic must be interesting to elementary students. Many use live animals as props in their presentations. “The animals are used as examples; [one] example this year is how geckos are adapted for their environment. The presentation is about conditions in different biomes; the team presents information on different geckos, and then brings out their own to demonstrate,” says Campbell.

Sometimes the animal “is a personal pet, but [students] have purchased their own or even borrowed [them] from friends. The chinchillas in the program this year were adopted by one of my students,” she notes.

“Once a team has been assigned to an animal, they are in charge of [its] care,” including taking animals home on long weekends and holidays, says Campbell. She adheres to Kansas guidelines on animals in the classroom when instructing her students.

“The first thing that each team has to do is to learn as much as they can about their animal, about how it lives in the wild and how to take care of it as a pet. The last thing students share in their presentations is all about having the animal as a pet: the cost and care involved and being a responsible pet owner,” Campbell explains.

“We go over what to do if [elementary] students are scared or hesitant about the animal. We have never had a student so scared that [he or she] cannot be in the same room, but we have had some [who] don’t want the animal near them. If that is the case, my students station themselves at the opposite side of the room with the animal and the [elementary students] come to them…The animal is in a carrier and out of sight until the end of the presentation,” says Campbell, and some animals are not removed from their carriers.

“I have only had one student [who] had to change to another class because [of the animals] in my classroom…I have had [Wide Horizons] students [who had] allergies (to the rabbit, for example), but they are fine as long as there is no contact. At the elementary schools,…[teachers] choose which presentations they want and will not book ones [involving animals students are allergic to],” she explains.

Simpson notes that Wide Horizons teachers “are insured under the school system’s policy” in case of any mishaps.

“I have had [staff] from the local zoo come to our class and share how they handle animal demonstrations. We also share stories from previous students. At the end of the school year, the teams write reflections that are useful for instructing the next year’s teams,” says Campbell. Students are graded based on elementary teachers’ rubrics and feedback, as well as on their final project for the class.

Wide Horizons began with a live animal focus, but during her tenure, Simpson needed to change the course to help elementary teachers meet “state science standards and benchmarks” and No Child Left Behind mandates, she explains. These changes included encouraging students “to research any literature involving their topic” and suggesting the younger students read it and presenting on other topics in biology and on chemistry, physics, and Earth science topics, she relates, adding, “To a little third-grade girl, seeing an older girl do chemistry and physics makes her think, ‘I can do that, too.’”

The high school students “grow so much in their presentation skills and confidence,” says Campbell, and “it’s not uncommon for them to go into teaching.”

Science Ambassadors

In Cumming, Georgia, Coal Mountain Elementary School and North Forsyth High School are partnering to stage Family Science and Engineering Nights at local elementary schools. The high school students serve as Science Ambassadors and hold family nights at 4–6 area schools annually. “We are now in [our] fourth year,” says Denise Webb, K–5 science and engineering teacher at Coal Mountain, who started the program with Donna Governor, a former North Forsyth science teacher (now assistant professor of science at University of North Georgia), and current co-facilitator and North Forsyth science teacher Charlotte Stevens.

Funding for Science Ambassadors comes from local business partners, and “we charge a small fee for supplies to the elementary schools, which [parent-teacher organizations] help pay,” she notes. “We wanted to make [the program] free to the elementary students and their families.”

Science Ambassadors’ mission “is for all [preK–5 students] and their families to engage in science and engineering activities that have real-world connections to develop [skills in]critical-thinking and problem-solving. Our goal is to inspire more students with the confidence to pursue careers in the STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) fields,” Webb explains. The elementary schools “are rural schools and need exposure to possible future careers that [students]otherwise may not be aware of…This program [also] provides high school role models of varied ethnicity and genders for the elementary students,” she points out.

“A second goal is for the [Science Ambassadors] to gain leadership skills and [develop] confidence in the science and engineering [skills] that can lead to careers in STEM,” she adds.

The Science Ambassador program is open to all North Forsyth High School students. “We have [advanced placement] students, special-needs students, and those who have no other niche and need service hours” among the Ambassadors, she reports. Candidates must have passing grades in their classes, a recommendation from a teacher, and no discipline referrals.

Those chosen for the program create science and engineering activities for stations they will run for elementary students on family nights. “I work with them on questioning skills and understanding the engineering design process,” Webb explains. “I give them science activities that match elementary standards.” Safety precautions are thoroughly covered in the practice sessions, she emphasizes.

Ambassadors must provide a list of supplies they will need for the next family night. “They have to follow through and learn to be prepared and thorough,” Webb maintains. She and Stevens take the Ambassadors to the elementary schools, but Ambassadors “are responsible for cleanup and a ride home,” she explains.

They also “design a brochure that explains all the science and engineering activities that were offered, steps to repeat them at home, and the science or engineering practices connected with the activity,” she relates. Local businesses can buy ads in the brochure.

The program reached more than 2,000 people last year because “students from other grade levels and schools” accompanied their families to the events, says Webb.

As a result of their efforts, “the Science Ambassadors have gained confidence in themselves. They have learned leadership skills, and their teachers [say] that…they are more engaged and motivated in their classes,” she reports. Representatives from the business partners have noted the Ambassadors’ prowess in “21st-century workforce skills like teamwork and communication,” she adds.

“Parents have told us that they are surprised at how well their elementary- aged child did in the science and engineering activities and plan to continue to look for ways to encourage them in STEM. They also commented on the professionalism and patience the high students showed their families. These are great qualities [Ambassadors] will [have] as they enter the workforce. [Parents] all overwhelmingly want us to come back again,” says Webb.

“We are helping other schools in our county start their own elementary/high school partnerships with similar programs because we cannot take on any more schools, and many more want to participate. We have also presented this program during [state and national education conferences] to assist others in getting this partnership started in their own districts,” she relates.

Science After School

KAST students from Annandale High School in Annandale, Virginia, teach elementary school students about aerodynamics using a paper plane demonstration.

“Youth teaching youth is [what’s special about] our organization,” says Jessica Yang, founder and chair of Kids Are Scientists Too (KAST; see http://kidsarescientiststoo.org), a nonprofit program in which high school and college students offer free hands-on science programming after school to elementary schools in Illinois, Washington, North Carolina, Maryland, Virginia, New York, New Jersey, Utah, and Ontario, Canada.Yang founded KAST because as high school students, she and CEO Jessica Sun wanted to “offer an enrichment program to make science learning experiences even better for students,” Yang explains.

Yang learned how through a year-long fellowship at LearnServe International, a Washington, D.C., nonprofit that helps high school students start social change programs. She received a $1,000 grant to start the business with support from LearnServe and Youth Venture. She also won $500 in a George Washington University business pitch competition. With these resources, Yang founded KAST Maryland in 2010. Sun established KAST Virginia soon afterward.

Yang, Sun, and other KAST volunteers created a series of one-hour lesson plans for fourth and fifth graders featuring “fun, interactive activities to get students excited about science,” says Sun. They used their “unique perspective as high school and college students,” their “studies in science in college,” and their “experiences working with kids” to create seven units with more than 60 lesson plans on various science topics, she relates.

The lessons were inspired by elementary and middle school curricula and “science experiments we’ve done in the past,” says Yang. During KAST’s pilot phase, “we received feedback from teachers [that] helped us ensure their quality.”

Since KAST volunteers usually teach students with a classroom teacher present, safety is ensured. “We have one KAST volunteer for every five elementary students, which helps us maintain a safe learning environment,” say Yang and Sun. KAST alumni—those who have graduated high school—serve as mentors to high school or college students who are new to the program.

Typically, “a high school student or teacher will reach out, and we’ll meet with [him or her] and [provide] all the materials needed to connect with schools and start a KAST program,” they explain. “We wanted the program to be free of charge to make it accessible to students from low-income families.”

In return for their service, KAST volunteers gain experience in leadership, organizing, recruiting, and public speaking, along with the satisfaction of “giving back to their community,” they conclude. “It is inspiring to see…some of the younger students [become] excited about science.”

This article originally appeared in the February 2017 issue of NSTA Reports, the member newspaper of the National Science Teachers Association. Each month, NSTA members receive NSTA Reports, featuring news on science education, the association, and more. Not a member? Learn how NSTA can help you become the best science teacher you can be.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

The Carson HookUpz 2.0: The Missing Link Between Camera and Eyepiece

By Martin Horejsi

Posted on 2017-02-03

Over the years I have held digital cameras and phones up to the eyepieces of telescopes, spotting scopes, binoculars, and most often microscopes to take pictures, capture video, and stream imagery to projectors and TVs. In all cases the idea was sound and the optics were fine, but the execution needed work even when duct tape was involved.

The HoldOnz 2.0 clamps securely to a Leica dissecting scope leaving one eyepiece open for critical focusing.

More than a few devices were employed to assist in holding the camera in the perfect position to look down the pipe of what instrument I was trying to leverage. Some adapters worked better than others, but the perfect clamp was illusive. The best solution was often dedicated electronic eyepieces that were expensive stand-along cameras of mild resolution. What was really needed was an elegant adapter that fits all phone cameras and all eyepieces. A pipe dream of sorts if you don’t mind the pun.

Enter the Carson HookUpz 2.0. The HookUpz 2.0 is a highly adaptable adapter that accommodates smartphones of many sizes on one end and eyepieces of many sizes on the other. The HookUpz 2.0 fits eyepieces diameters from 25mm to 58mm, and holds smartphones sizes from iPhone 4 through iPhone 7 Plus and other phablets.

The iPhone and HoldOnz 2.0 are not much bigger than the superb Leupold Compact Spotting Scope making this mini optics platform worth it’s minuscule weight in golden views.

On the phone-side, the Carson HookUpz 2.0 uses a pincher clamp to grab the lower edges of the phone, and there is a single top clamp that complete the “three-fingered” grip on the phone. A combination course/fine screw adjusts the sideways motion of the phone in order to center the camera over a hole that is in turn the center of the eyepiece clamps on the reverse side. Here is the instructional manual for the Carson HookUpz 2.0.

Even binoculars with fold down eyepieces present little problem for the HoldOnz 2.0. Clamped to this pair of Leupold Mojave BX-3 Pro Guide binoculars make tremendous use of the incredible HD optics available today in modern binocular designs. Additionally, by using the HoldOnz 2.0 and a smartphone with a pair of binoculars, the view can be shared with a small group, and of course captured and/or streamed live as images or video. These Leupold binoculars are a ten power meaning that a comparable lens for a full-frame digital camera would be a 500 millimeter lens!

On the eyepiece side, two pair of spingloaded clamps grab the eyepiece with enough strength to keep the phone still even when on on something in motion like on a pair of binoculars. The Carson HookUpz 2.0 works great with corner-placed cellphone cameras as well as those those centered in the middle of the back of the phone. There is also a optic clamp lock that is especially helpful with smaller eyepieces when using the minimum clamp spring tension.

Once the phone is in place, the camera’s zoom feature will fill the frame with the eyepiece’s field of view. You can continue to zoom in if you like to add some digital enlargement to the optical magnification of your optic. The camera’s focus and exposure should work fine as long as the eyepiece is also in focus.

Once the system is in place, you can take pictures and shoot video with surprising clarity through microscopes, dissecting scopes, telescopes, spotting scopes, binoculars, and any other tubed optic with a eyepiece within the HookUpz 2.0’s clamping range. In the off-chance that phone camera needs some space between it and the eyepiece, a spacer for just such a purpose is included. Additionally a very nice zippered hardcase is included.

As you notice in the name, the Carson HookUpz 2.0 is not the first attempt at this type of product from Carson. The 2.0 design is much better and stronger than its predecessor, but there are some excellent tips and tricks that apply to using a clamp device, adjusting the phone settings, taking pictures and video, and even using headphone/earbuds volume control as a shutter release that were popularized with prior clamps. Here’s a great video with just such “hacks” directly from Carson.

Once you get the hang of the Carson HookUpz 2.0, you can clamp-in your phone and mount it on an optic in maybe 15 seconds. Not that it’s a race, but other clamps I’ve used have required screws and bolts, case installing, and alignments before attempting to the whole contraption to an eyepiece. With the Carson the two pair of auto-centering eyepiece clamps make mounting it a snap.

Using the Carson HookUpz 2.0 can turn an individual viewing experience into a collaborative group activity. By projecting the instrument’s image onto a smartphone screen or larger, a whole new dimension of of teaching and learning opens up. Add the ability to digitally capture the imagery and the visual universe just gained yet another dimension. Modern cellphones are state-of-the-art digital cameras with incredible image processing chips and software. In fact most recent iPhones have camera chips and lenses that rival dedicated DSLR cameras in picture quality. So sharp images taken through scopes of various flavors can be blown up to very large proportions providing a post-viewing experience with endless uses.

There are many camera/phone functions, apps, and utilities that can be used including the regular camera choices of photos, video, slo-mo, and time-lapse. Video can also be used within FaceTime and other app-based video conferencing programs as well. Science oriented apps that use the camera can work magic, and the latest generations of Apple TVs can fire up the captured imagery onto screens from up to 10 meters away.

Apps such as Explain Everything (one of my favorites) allows for real-time annotation on camera-captured images, and video capture of that annotation over time with quick upload to Youtube if you like.

While there is still room for improvement with the Carson HookUpz 2.0, such as constructing it out of titanium, or at least aluminum instead of flexible plastic, or having fold-up clamps so the HookUpz would fold flat for pocket storage. Or even maybe a phone case/clamp combination for us power users. Either way, the Carson HookUpz 2.0 is one of those gadgets that once you use it, you will, pardon the pun again, be hooked.

Over the years I have held digital cameras and phones up to the eyepieces of telescopes, spotting scopes, binoculars, and most often microscopes to take pictures, capture video, and stream imagery to projectors and TVs. In all cases the idea was sound and the optics were fine, but the execution needed work even when duct tape was involved.

The Micro Phone Lens: A Tiny Solution to a Huge Problem

By Martin Horejsi

Posted on 2017-02-02

Other than computer code, the Micro Phone Lens just might be the lightest accessory you can add to your tablet or phone. Weighing in at a fraction of a gram, the tiny lens leverages the optical power of existing cameras on phones and tablets. And like a contact lens, its power is not measured in size but in performance.

Taking close-up photos and video, and I mean really close-up, pushes not only the limits of phone camera technology, but also the physics of visible light. In order to refract the light waves enough to focus on a subject that is a few millimeters from the lens, a significant amount of light-bending convex transparent material must be in the path of the light. Of course it would be easy to do that when the camera was made, but since most photos are not extreme close ups, the lens optics favor the more distant subjects. Close-up or macro photography captures details much smaller than what an unaided human eye can see. So macro can be the details on a penny, or a pinhead, or even a pinpoint.

One major difference between the Micro Phone Lenses and other clip-on accessory lenses is that the Micro Phone Lens is about the same size or even smaller than the camera lens on the device so it fits directly on the camera and is unaffected by anything surrounding the lens. Any lens accessory larger than the camera can be affected by a phone or tablet case. And worse, any space between the accessory lens and the camera lens wreaks havoc with the camera’s ability to focus, not to mention the tunneling or vignetting that separating causes.

A Kickstarter Campaign in 2013 launched the 15x Micro Phone Lens after the original two lenses, a 4x and 8x were the brainchild of the inventor Thomas Larson who dreamed up the idea while a mechanical engineering student at the University of Washington in 2012. And a second Kickstarter funded the R&D and production of a 150x lens in 2015.

In particular, the 15x and 150x are true micro lenses that easily see well below the naked human eye threshold. But that power in shaky hands will produce poor quality images. Optically, there are a set of undebatable rules that when violated produce blurry images, and when followed will allow stunning images to be captured all day long.

The rules include:

1) The higher the magnification, the thinner the depth of field (thickness of what’s in focus).

2) Higher magnification also magnifies camera movement.

3) The amount of light necessary increases with magnification.

4) The working distance between subject and camera is reduced as magnification increases.

5) Bright lighting solutions are necessary to illuminate highly magnified subjects.

6) Perfect timing between a focused image and the shutter capturing the picture is critical.

7) The picture or video must be taken when exposure is perfect and the subject is in focus. With auto-adjusting cameras, the image often constantly swings between good and bad. Luckily a near-unlimited supply of pictures can be taken minimizing the the chance you walk away with nothing useful.

The Macro Phone Lenses are made of a special scratch resistant soft plastic. While I prefer glass lenses when available, or even sapphire lenses like on the new iPhones, the other features of the Micro Phone Lenses provide many more advantages compared to the traditional designs. The adhesive properties of the soft plastic keep the little bubble stuck to the camera protecting the lens as you get close to subjects.

I was a little skeptical at first that the adhesivness would continue after plenty of fingerprints and dust got on the lens, but rarely did I need to wash off the lenses in warm water to regenerate their stickiness. However, I wouldn’t advise slipping the lensed camera into and out of a pocket. Most likely the lens will fall off, but if not, it will be covered with lint.

The images the Macro Phone Lens captures are excellent given the absolute simplicity of this product. Of course they are not as good as my Leica microscope, but at one one-hundredth the cost, and infinitely lighter and smaller, the MicroPhone Lenses leverage existing phones, tablets and even laptop computers in ways a microscope could only dream of.

The focal point of the 15x is well in front of the lens, but the 150x image requires a pressure focusing that in turn requires some precision and fine motor skill dexterity. Using a special soft and compressible outer ring the same diameter of the Micro Phone Lens, a traditional microscope slide can be placed upon lens and gently and slowly depressed until focus is achieved. It’s a simple solution to an expensive problem.

Someday I expect to see Thomas Larson, the creator of MicroPhone Lens on a TED stage for changing medicine in third world countries. By using existing and ubiquitous technology to view blood smears and cell structures, it’s possible for remote, poor, and even war-torn sites to inspect or email critical medical imagery. But in the meantime, there is a big wide world of very tiny things that fit nicely into the science curriculum. The macro viewing advantages and low cost of the Micro Phone Lens crosses all grade bands and science subjects. So for about the cost of a single traditional microscope, you could leverage phones and tablets and put microscopy in every student’s hands.

Other than computer code, the Micro Phone Lens just might be the lightest accessory you can add to your tablet or phone. Weighing in at a fraction of a gram, the tiny lens leverages the optical power of existing cameras on phones and tablets. And like a contact lens, its power is not measured in size but in performance.

Legislative Update

Committee Approves DeVos Nomination, Senate Vote Expected Next Week

By Jodi Peterson

Posted on 2017-02-02

On January 31, the Senate Health Education Labor and Pensions Committee voted to approve the nomination of Betsy DeVos as Secretary of Education by a party-line vote of 12 to 11.

After the committee’s vote two key Republicans–Republican Sens. Susan Collins of Maine and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska–said they would vote against DeVos’ confirmation on the Senate floor. All Democrats have unified against the DeVos nomination and the nomination vote count now stands at 50 to 50. The Republicans 52- seat majority in the Senate means a “no” vote from one more Republican senator could derail DeVos’ nomination since Vice President Pence would cast the tie-breaking vote.

The full Senate will begin debating the DeVos nomination and a final Senate floor vote is expected on Monday or Tuesday.

As reported in a previous issue of the NSTA Legislative Update there was a great deal of opposition to the DeVos nomination. Thousands are calling their Senators to oppose her nomination. The NEA reports that over one million people used an online form during the past three weeks to email their senators to urge opposition to DeVos.

Prior to the committee vote, DeVos submitted written answers follow-up questions submitted by HELP Senators. Many of these questions/answers focused on STEM, CTE, standards, and more (if you are interested in reviewing her answers about science/STEM, email me at jpeterson@nsta.org)

NSTA and Leading Scientific Groups Urge Trump to Rescind Immigration Order

NSTA joined 164 scientific, engineering and academic organizations on a letter to President Trump asking him to rescind the executive order on immigration and visas issued on January 27, declaring it “damaging to scientific progress, innovation and U.S. science and engineering capacity.” Read more here.

March for Science Set for April 22

The March for Science campaign has scheduled its demonstration in Washington for Earth Day, April 22. Read more here.

Stay tuned, and watch for more updates in future issues of NSTA Express.

Jodi Peterson is Assistant Executive Director of Communication, Legislative & Public Affairs for the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) and Chair of the STEM Education Coalition. Reach her via e-mail at jpeterson@nsta.org or via Twitter at @stemedadvocate.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

On January 31, the Senate Health Education Labor and Pensions Committee voted to approve the nomination of Betsy DeVos as Secretary of Education by a party-line vote of 12 to 11.