Resource: Helping children rebound after a natural disaster

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2012-10-31

The ChildCareExchange’s daily newsletter, the ExchangeEveryDay, sent out a message about the free Teaching Strategies booklets on Helping Young Children Rebound After a Natural Disaster, one for teachers of infants and toddlers, and one for teachers of preschool age children. Thank you to Teaching Strategies author Cate Heroman and mental health expert Jenna Bilmes for these resources.

![]()

![]()

Teaching with current events

By Christine Royce

Posted on 2012-10-28

In this month’s Leaders Letter, the topic for the building content area focused on the recent record setting sky (or should we say space) jump conducted by Felix Baumgartner. The undertaking was sponsored by Red Bull Stratos which has a history of sponsoring extreme sports. For more information on their Mission to the Edge of Space visit their webpage which provides information associated with the science, technology, team and other mission aspects.

I’m not sure about you, but on that particular Sunday afternoon, I sat in my living room totally mesmerized by the live coverage of this event (Okay I confess—I would LOVE to do something like that someday—whether my mother calls me crazy or not!!!!) and totally plugged in to the social media outlet as myself and other friends from across the country interacted asynchronously through outlets such as Twitter and Facebook. This was not the first time that social media provided updates and information from colleagues across the country on a current event.

Most recently it was the final trip of the Space Shuttle from Florida to California. Flybys over the flight path were expected and it was like watching the entire event through the eyes of my friends as they posted pictures from Florida, Texas, Arizona and California. I could not have had a better seat for viewing either of the current and momentous events unless I was there in person.

Current events such as the brewing of Hurricane Sandy at the moment and the impending “Frankenstorm” as it has been labeled are ways to engage students in science topics. We as science educators have a great opportunity to engage and interest students in their real world thanks largely to the real world!! Recent years current events that I can think of include the freak snowstorm last October (with many NSTA members stuck in Hartford for a few extra days); the Earthquake that rocked the east coast in August 2011; the Tsunami that hit the west coast during the San Francisco conference in March 2011 and was a result of the great Japan earthquake that caused massive amounts of damage and in particular concern over the nuclear plants. Furthermore, the use of social media to share information allows us to have massive amounts of information (some accurate and some inaccurate) available about a particular topic almost immediately.

The opportunity to engage students with current events and keep them connected through social media is ever ready and available. To continue this conversation, it would be great to hear what others have chosen as current events to teach science and what the focus of the lesson was as well as how social media played a role in sharing this information.

In this month’s Leaders Letter, the topic for the building content area focused on the recent record setting sky (or should we say space) jump conducted by Felix Baumgartner. The undertaking was sponsored by Red Bull Stratos which has a history of sponsoring extreme sports. For more information on their Mission to the Edge of Space visit their webpage which provides information associated with the science, technology, team and other mission a

Online events and resources via Twitter

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2012-10-26

Even if you don’t tweet to any followers, it’s a great idea to use Twitter for updates, news, and suggestions. #scichat and #nsta are two hashtags that are a must for science teachers. Just this morning, I saw quite a few online events and resources that were worth learning more about:

Cell Day —  The National Institute of General Medical Science (NIGMS) will host an interactive Web chatroom about the cell for middle and high school students. You can join in on Friday, November 2, 2012, anytime between 10:00 a.m. – 3:00 p.m. EDT. Even if you can’t participate in the event, their Cell Day online resources on look good

The National Institute of General Medical Science (NIGMS) will host an interactive Web chatroom about the cell for middle and high school students. You can join in on Friday, November 2, 2012, anytime between 10:00 a.m. – 3:00 p.m. EDT. Even if you can’t participate in the event, their Cell Day online resources on look good

T undra Connections — This project features live, free broadcasts from the tundra during the annual polar bear migration in Churchill. There is a section for educators that includes archived broadcasts, and unit and lesson plans.

undra Connections — This project features live, free broadcasts from the tundra during the annual polar bear migration in Churchill. There is a section for educators that includes archived broadcasts, and unit and lesson plans.

Several colleagues mentioned the interactive Rock Cycle, which guides students through a discussion and examples of rock types. I noticed that this is on the ICT Magic website, which is a treasure of interactive animations on many topics (see the index in the left margin). Within a few minutes, I was exploring a virtual volcano and the factors that affect a volcanic eruption. ICT Magic is a wiki that synthesizes resources from other sources such as pHET, Discovery, and the Annenberg Foundation. I could see showing students the site and asking them to explore their interests!

I’m also using Twitter to keep abreast of Hurricane Sandy and its impact on the Northeast. @usNWSgov and @usNWSgov

Even if you don’t tweet to any followers, it’s a great idea to use Twitter for updates, news, and suggestions. #scichat and #nsta are two hashtags that are a must for science teachers. Just this morning, I saw quite a few online events and resources that were worth learning more about:

Hard-to-teach concepts

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2012-10-25

As the S&C editor notes, most of us have had struggled with hard-to-teach concepts. But as one article states, Hard to Teach Does Not Mean Impossible if the classroom is an environment in which students feel comfortable questioning and sharing their thinking, if preconceptions or misconceptions that might affect learning are identified, and if connections are made with other subject areas. (Talking About Shadows describes this “friendly talk.”)

As the S&C editor notes, most of us have had struggled with hard-to-teach concepts. But as one article states, Hard to Teach Does Not Mean Impossible if the classroom is an environment in which students feel comfortable questioning and sharing their thinking, if preconceptions or misconceptions that might affect learning are identified, and if connections are made with other subject areas. (Talking About Shadows describes this “friendly talk.”)

The featured articles in this issue have suggestions for addressing hard-to-teach concepts with planned and purposeful learning activities, including identifying misconceptions, rubrics, lesson plans, and examples of student work. (It may be a coincidence, but it seems that most focus on physical science concepts. Hmm.) NSTA’s SciLinks has collections of vetted websites with background information on the concepts and additional teacher resources:

- Changes Matter! [SciLinks: Physical/Chemical Changes, Law of Conservation of Matter]

- Experiencing Friction in First Grade [SciLinks: Friction]

- Talking About Shadows, Modeling Light and Shadows [SciLinks: The Sun]

- How Does Force Affect Motion? [SciLinks: Forces and Motion (K-4), Forces and Motion (5-8), Friction, Force of Gravity, Gravity]

- May the Magnetic Force Be With You [SciLinks: Magnets, Magnetism, Magnetic Fields]

- Shining Light on Misconceptions [SciLinks: Light, Light and Color]

- Energy Makes Things Happen [SciLinks: Energy, Sources of Energy, Energy Transformations, Winds]

- Does Technology Evolve? [SciLinks: Technology and Society, Inventions/Inventors]

- More Is Less [SciLinks: Parts of a Plant, Plant Growth]

- The Spider Files [SciLinks: Arthropods]

- Big Ideas for Little People [SciLinks: Biological Evolution, Vertebrate Evolution]

Many of these articles have extensive resources to share, so check out the Connections for this issue (October 2012). Even if the article does not quite fit with your lesson agenda, there are ideas for handouts, background information sheets, data sheets, rubrics, and other resources.

iPad Science Exploration: Visualizing Brainwave Entrainment

By Martin Horejsi

Posted on 2012-10-24

Brainwave entrainment or “brainwave synchronization,” is any practice that aims to cause brainwave frequencies to fall into step with a periodic stimulus having a frequency corresponding to the intended brain-state (at least according to Wikipedia).

I have a fascinating App on my iPad called simply Headache. It’s introduction in the App Store reports, “Advanced Brainwave Entrainment is used to synchronize your brainwaves to deeply relaxing low-frequency alpha, theta and delta waves to help provide headache relief through deep relaxation. “

For $0.99, I downloaded the App to play with it.

Right away I could tell it was tapping into something inside my head. It was hard to explain, but perhaps a picture would help. Visualization is an important variation of communication, and as they (whoever they is?) say, a picture is worth a thousand words.

The Wikipedia entry provides two graphics of interest in my exploration; Monaural beats and Binaural beats.

Monaural beats, again according to Wikipedia, are derived from the convergence of two frequencies within a single speaker to create a perceivable pulse or beat.

On the other hand, Binaural beats are “perceived by presenting two different tones at slightly different pitches (or frequencies) separately into each ear. This effect is produced in the brain, not in the ears as with monaural beats.”

So if I understand this correctly, monaural beats are heard with the ears, while binaural beats are heard with the brain. WOW! I guess that explains why I could feel the sound in my head, not just heard it with my ears.

In order to “picture” the sound (I bet there’s no noun I can’t verb), I needed to be able to capture an image of the sound both as a traditional recording of compression and rarefaction of air, as well as the sharper vibrations moving through solid materials.

The movement of air was easy. I just propped up a mic next to the Bluetooth speaker I had paired to my iPad and used GarageBand to record the audible sound. Garage Band gave me both a picture and a sound file that you can listen to here: brainwave entrainment.

A visualization from GarageBand of the sound file available above.

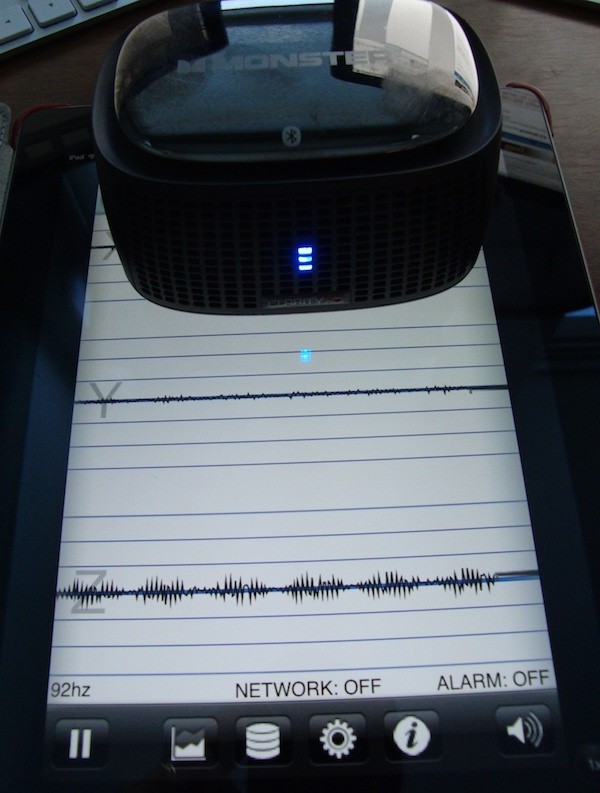

But I wanted something more dynamic. Something that gave me more of a real-time image of what was happening at the exact moment I was hearing/feeling it. Not that there is a delay with GarageBand, but I wanted something more like how a seismograph presents a graphic showing the subtleties of vibrations as I was hearing them (or not hearing them since subsonic frequencies are part of the Headache App’s equation. As “they” say, there’s an App for that, and it’s called iSeismometer. And it’s free.

The iPad screen shows the visualization that the App iSeismometer shows for the signal. The bluetooth speaker is sitting directly on the iPad screen thus vibrating the iPad and its built-in accelerometers. Note that only the z-axis contains the beats.

With Headache running through the speaker, and the speaker sitting on the iPad screen, iSeismometer displayed the sound, which, interestingly, was almost all in the Z-axis of motion (but I suspect that is just a function of the interaction of the speaker and its placement on the iPad’s glass screen).

The speaker on the left emits the audio signal from the Headache Relief App (icon visible in the lower right) while a microphone records the sound from the speaker for import into GarageBand.

As usually happens, more questions were generated then answered. Right now, I’m wondering if I could match light output and frequency cycling with the sound to create a stronger inner-brain visual effect. But what if the light and sound were slightly out of phase? Could a seizure be induced? I once had a dog that would have a seizure about six hours after being exposed to flashing police or fire engine lights. And we all remember the famous scene in the movie The Andromeda Strain. But I digress.

A big unknown here is the stereo vs. mono issue. Headphones are distinctively stereo. Although a single speaker may project in stereo, the App iSeismometer might only be able to detect a single channel sound thus combining both of the signals that make stereo into a single mono visualization. Unless, the z-axis phenomenon is involved. Hmmm. More questions.

In the end, however, I think the main takeaway from this 30 minute desktop science exploration is that devices like the iPad have tremendous potential in the science classroom. Far beyond the keyboards and covers that often dominate tablet discussions in education.

Brainwave entrainment or “brainwave synchronization,” is any practice that aims to cause brainwave frequencies to fall into step with a periodic stimulus having a frequency corresponding to the intended brain-state (at least according to Wikipedia).

Writing in science class

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2012-10-24

We’re having a discussion in our secondary school science department. Some of us think our lessons should incorporate more opportunities for students to learn how to write, while others maintain there’s little time for writing and that’s the job of the English teachers. Who is correct?

We’re having a discussion in our secondary school science department. Some of us think our lessons should incorporate more opportunities for students to learn how to write, while others maintain there’s little time for writing and that’s the job of the English teachers. Who is correct?

—Mitch from Ohio

Yours is a timely question. I’m currently reading The Framework for K-12 Science Education The Framework describes eight “practices” scientists and engineers use, including Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information.* As described in the Framework, “…learning how to produce scientific texts is as essential to developing an understanding of science as learning how to draw is to appreciating the skill of the visual artist.” (p. 75) Even if our students do not become professional scientists or engineers, writing is part of many jobs and careers in business, medicine, the arts, and the social sciences.

At an inservice event I attended, a museum herpetologist described his work to a group of teachers. His research focused on a longitudinal study of frog populations in the Northeast United States, but he said that a good portion of his day was spent writing—notes, memos, observations, summaries, reports, journal articles, blog entries, and letters.

This type of writing is different from the narrative and creative writing that students do in Language Arts (LA) classes. While our LA colleagues teach sentence structure and correct usage that applies to all writing, it’s unrealistic to assume they will also teach students the nuances of writing for science purposes. So it is indeed the job of the science teacher to help students learn to communicate what they know and understand through informational writing.

In terms of writing, according to the Framework, by grade 12 students should be able to

- Use words, tables, diagrams, and graphs to communicate their understanding.

- Recognize the major features of science and engineering writing and produce written and illustrated text that communicates their ideas and accomplishments.

Writing in science is not necessarily limited to traditional term papers or reports. If you have students write lab reports, make journal entries, summarize their learning, contribute to a class blog, take their own notes, or respond to open-ended items on an assessment, you’re already helping students develop their writing skills.

It’s interesting that the Framework seems to go beyond traditional writing to include organizing information and communicating through diagrams, graphs, mathematical expressions, tables, and other illustrations. I attended a professional development workshop during which a college physics professor eloquently described graphs and tables as ways of telling stories. He displayed a graph and asked the teachers to create a narrative of what the graph said. Seeing their questioning looks, he modeled how to do this. When the light bulbs went off, he displayed another graph and the teachers responded enthusiastically.

You can’t assume students will come to your secondary classes with all the writing skills they need. You can teach students about writing, but the best way to develop skills is to have them write—often and a lot—through planned and purposeful activities. Just as the physics professor did, modeling is essential. Show students what effective science writing looks like (using both words and illustrations). Show them examples of ineffective writing and ask them to clarify it. Write along with the students yourself and display your work. Show them how to format text structures such as bulleted or numbered lists, headings, or tables.

You can’t assume students will come to your secondary classes with all the writing skills they need. You can teach students about writing, but the best way to develop skills is to have them write—often and a lot—through planned and purposeful activities. Just as the physics professor did, modeling is essential. Show students what effective science writing looks like (using both words and illustrations). Show them examples of ineffective writing and ask them to clarify it. Write along with the students yourself and display your work. Show them how to format text structures such as bulleted or numbered lists, headings, or tables.

When evaluating student writing, it’s easy to fall into the trap of trying to edit their work. Commenting on every misspelled word and every grammatical error is time consuming, and seeing a page full of corrections can be discouraging for any writer. I took the advice of the LA staff and focused less on conventions and usage and more on the content and clarity of the writing (I did require students use complete sentences, spell the words on the word wall correctly, and label all numbers). I framed this in the context of communicating clearly—”You have important things to say. When you write clearly, we can all understand what you mean.” Your rubrics may need to be adjusted for the grade level of the students, their prior experiences in science writing, and their facility with the English language.

Like many of your students, I was a reluctant writer. But thanks to the persistence and feedback from one of my high school teachers (thank you, Sister Elizabeth), I realized I could write informational text. I hope you will take the time to help your students develop their own skills and confidence in science writing.

*Resources

The Framework for K-12 Science Education – Free PDF version from National Academies Press

The NSTA Reader’s Guide to A Framework for K–12 Science Education – Free e-book with overviews and synopses of key ideas, an analysis of what is similar to and what is different from the NSES, and suggested action to help readers understand and start preparing for the Next Generation Science Standards.

NSTA will be hosting a web seminar on Preparing for the Next Generation Science Standards—Obtaining, Evaluating, and Communicating Information. In addition to the live session, it will be archived for future viewing.

From NSTA Press:

How to… Write to Learn Science

Science the “Write” Way

Images: http://farm4.static.flickr.com/3072/3110638201_0b7e66a19a.jpg and http://farm1.staticflickr.com/66/198046070_730a2474d2_q.jpg

We’re having a discussion in our secondary school science department. Some of us think our lessons should incorporate more opportunities for students to learn how to write, while others maintain there’s little time for writing and that’s the job of the English teachers. Who is correct?

We’re having a discussion in our secondary school science department. Some of us think our lessons should incorporate more opportunities for students to learn how to write, while others maintain there’s little time for writing and that’s the job of the English teachers. Who is correct?

—Mitch from Ohio

Heredity and genetics

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2012-10-20

Middle school students are curious about genetics, and most have an awareness of the use of genetic testing and DNA samples from popular television programs. The featured articles this month show how teachers can capitalize on this interest with interesting and relevant learning experiences.

Middle school students are curious about genetics, and most have an awareness of the use of genetic testing and DNA samples from popular television programs. The featured articles this month show how teachers can capitalize on this interest with interesting and relevant learning experiences.

Genes Are Us describes two activities that can help students understand the uniqueness of an organisms DNA and the concept of DNA fingerprinting. Who done it? The case of the suicidal murder victim shows a real-life application of the processes of microscopy, chromatography, blood typing, and gel electrophoresis as students attempt to collect and analyze evidence. Both of these classroom-tested activities capitalize on the interests and experiences of middle schoolers. [SciLinks: Blood Type, DNA Fingerprinting, Electrophoresis, Forensic Science, Microscopes, Paper Chromatography]

According to the author, the activities in Natural Selection and Evolution: Using Multimedia Slide Shows to Emphasize the Role of Genetic Variation evolved from a student misconception that adaptations are a result of environmental challenges rather than from genetic variations. She uses resources from Learn.Genetics, a comprehensive collection of information and activities on genetics, bioscience and health topics (there’s enough on this site for an entire course).

Creative Natural Selection takes traditional activities and kicks them up a notch to involve student creativity and creativity. The article contains resources, rubrics, and descriptions of “Predict a Pollinator” and “Predicting Natural Selection with Camouflage” [SciLinks: Pollination, Animal Camouflage]

In a Phenylketonuria Genetic Screening Simulation, students assume the role of lab technician as they engage in a simulation of this common test for newborns. The author provides samples documents for student notes and data entry, the procedure for the simulation, and background resources. [SciLinks: Genetic Diseases, Screening, Counseling]

The authors of Learning About Genetic Inheritance Through Technology-Enhanced Instruction used the WISE 4 resource to develop a module in which students use technology to “see” the possible phenotypes and genotypes of offspring. The module has embedded assessments and the article has a daily overview and screen shots of the unit. [SciLinks: Heredity, Genotype / Phenotype, Punnett Squares]

Invertebrate diversity tally

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2012-10-16

Students at Bailey’s Elementary School for the Arts and Sciences are finding out how many different kinds of invertebrates live in their schoolyard. Using a poster showing the invertebrates that are common in a Northern Virginia pollinator garden to familiarize themselves with these small animals, second-graders went out into the garden to see what they could find. They also used the poster to collect data. Every time they saw an animal such as a roly-poly or Monarch butterfly caterpillar, they put a tally mark on the laminated poster using a dry erase marker. The purpose of this activity was to notice how many kinds of invertebrates there are in a small garden, a diversity of life.

Most of the classes found about 25 different species during their 15 minute search. Students may come up with questions while searching. Teachers can record the students’ questions and later talk about how the class might find answers to the questions. Are any of the questions investigable, that is, can the students investigate to find answers or is that beyond their capabilities or the scope of a school year? Some questions can be researched in books, online, or by asking experts. Others can be answered with student data collection, analysis and discussion. One such question might be, “Will we always find roly-polies under the log?” How many days would your students have to collect data to feel that they had answered this question?

Most of the classes found about 25 different species during their 15 minute search. Students may come up with questions while searching. Teachers can record the students’ questions and later talk about how the class might find answers to the questions. Are any of the questions investigable, that is, can the students investigate to find answers or is that beyond their capabilities or the scope of a school year? Some questions can be researched in books, online, or by asking experts. Others can be answered with student data collection, analysis and discussion. One such question might be, “Will we always find roly-polies under the log?” How many days would your students have to collect data to feel that they had answered this question?

Editor Linda Froschauer wrote in her column in the December 2010 Science & Children, “Students have many questions, but in an inquiry setting they need to be taught how to formulate questions that will provide them with opportunities to investigate and ultimately develop understanding.” She says that students need ample time to explore a phenomenon before they can design questions that they can investigate.

To ask questions and share your experience with science inquiry, join the conversation in The NSTA Learning Center’s Elementary Science Forum, “Helping Elementary Teachers Embrace Inquiry.” Register at no cost to read and participate.

Students at Bailey’s Elementary School for the Arts and Sciences are finding out how many different kinds of invertebrates live in their schoolyard.