The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2019-10-15

In the October 2019 Early Years column in Science and Children, Anne Lowry, a preK teacher at Aleph Academy in Reno, Nevada, and I wrote about problem-solving experiences that took place in our classrooms. Engineering design opportunities in early childhood may come about by following children’s interests and also when adults provide both materials and challenges. “Engineering is a systematic and often iterative approach to designing objects, processes, and systems to meet human needs and wants” (NRC pg 202). The processes of engineering include testing and revisions, and using engineering habits of mind (Counsell 2015).

Fireworks!?

In Anne’s a mixed-age classroom of 3-to-5 year olds, not all children are able to draw possible solutions to engineering problems because they may be still developing the necessary fine motor skills. However, by creating verbal designs, children can describe their design quite successfully. In the process of creating verbal designs, the children build on what they already know, individually and sometimes collectively, if in groups. The result can be a clear design with concrete testing questions.

Educators who can be open to children’s loftiest ideas—even those that seem impossible at first—honor children’s capabilities and thinking. Consider how you might be able to say, “Yes, and…” and help children begin problem solving by asking open-ended questions. Make firecrackers at school!? The children wanted to wanted to build their own fireworks and although the teachers ruled out the use of explosives, several children did not give up on the idea of fireworks.

They worked together and identified questions about the design: 1.) What materials to use, 2.) How to make the fire cracker “explode,” and 3.) What to use to make it light up. Images of firecrackers suggested using material with a cylindrical shape—paper towel tubes. Anne asked prompting questions, including “What do you do to make objects move?” The children discussed and tested several methods before including a balloon into their design.

Two materials were proposed for the “light.” Isla and Eve proposed using tiny rounds collected when using hole punches (“confetti”), and Cohen wanted to try miniature pom poms. The children decided this was a testable question and gathered both materials.

Throughout their process the children used engineering habits of mind: systems thinking, creativity, optimism collaboration, communication, and attention to ethical considerations (the impact of engineering on people and the environment) (Counsell 2015). The success of their fireworks was confirmation that fostering children’s capacity to design and construct their designs helps them develop critical thinking skills and engineering habits of mind.

o—————————————o

Engineering Design with Cardboard

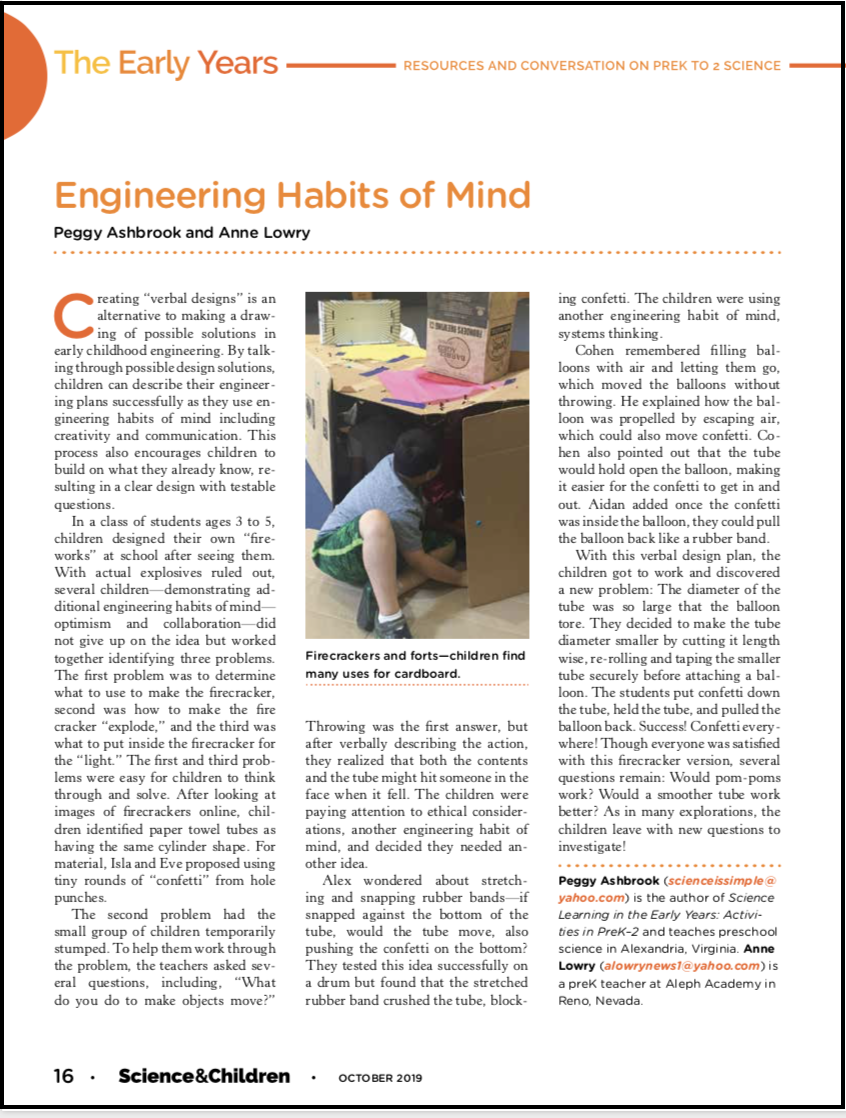

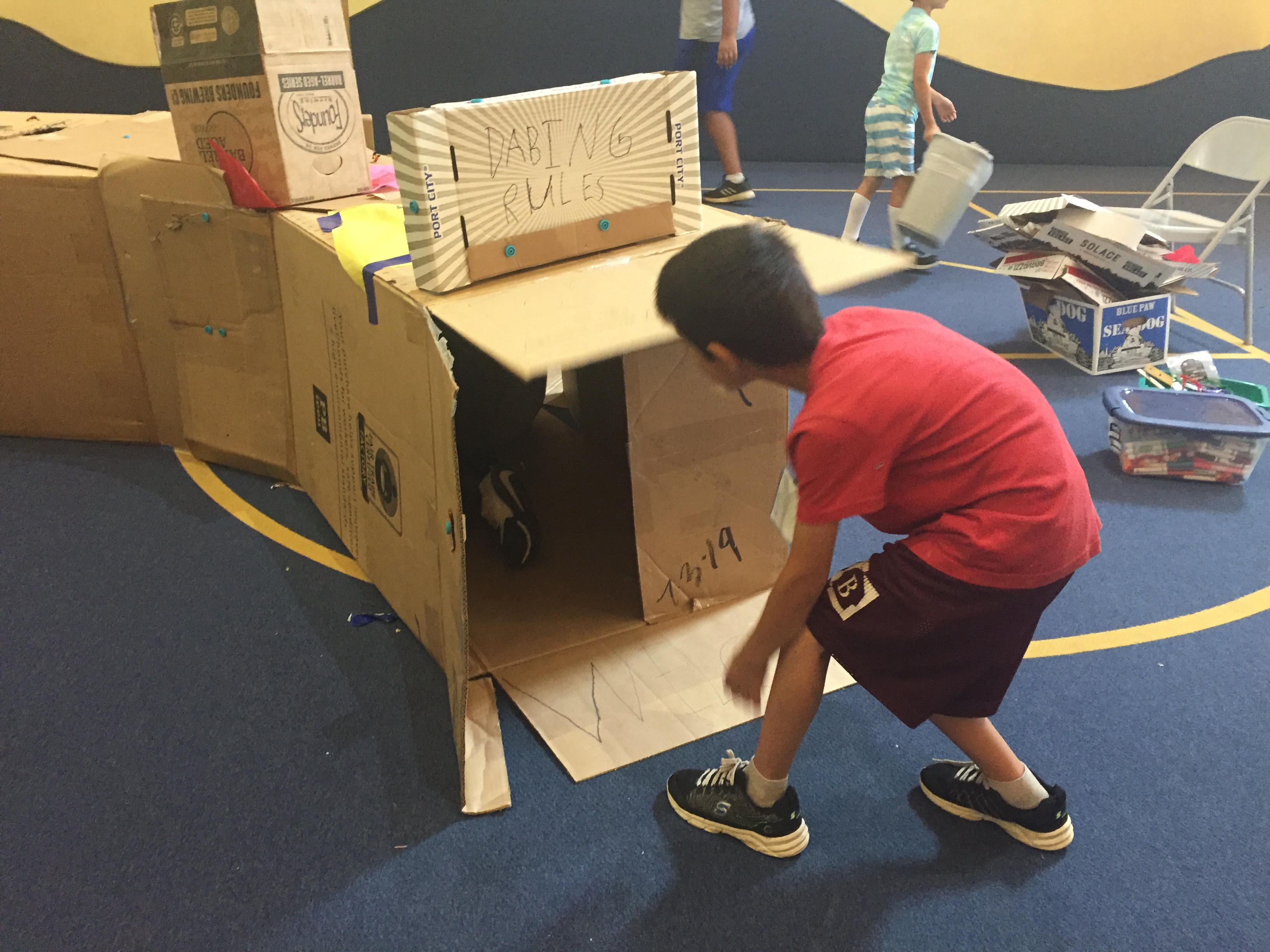

Teaching a summer camp class at the Pinecrest Pavilion Summer Camp on using cardboard in construction of designed structures provided an opportunity for me to see how the developmental age and prior experience of students directs the choice of projects and tools. Kindergarten to grade 2 children were enrolled in the morning session and the afternoon session was 3rd-5th.

Designing and building a marble run was our first project— re-using materials such as cardboard tubes and boxes, construction paper, and egg cartons, with tape. I provided some precut pieces of tape for the younger group and set up “tape stations” with scissors. The older group tended to take the rolls of tape to their table where it disappeared under their materials! The younger children built shorter structures. Seeking to make long ramps, the older children hastily rolled construction paper into long, structurally weak tubes.

There was just as much difference in skill sets within the age groups as there was between them. Some children needed to hear others’ ideas before they could settle on a plan and get to work. Some were focused on completion and didn’t spend much time making a stable structure or creating a clear pathway for the marbles. Others worked so long on perfecting one aspect of their marble run that they ran out of time that day to make the rest of what they envisioned.

To become proficient at making well-formed objects of any kind (that meet their own expectations), children need more time than five half-days to mess about with materials, design, build, test, and re-design no matter what material is involved, but especially if they haven’t previously used the material. That very important open-exploration period strengthens children’s experience with the properties of materials and ability to imagine and design. Developing this knowledge also involves developing fine motor skills, patience, and spatial awareness, and is a lot of fun!

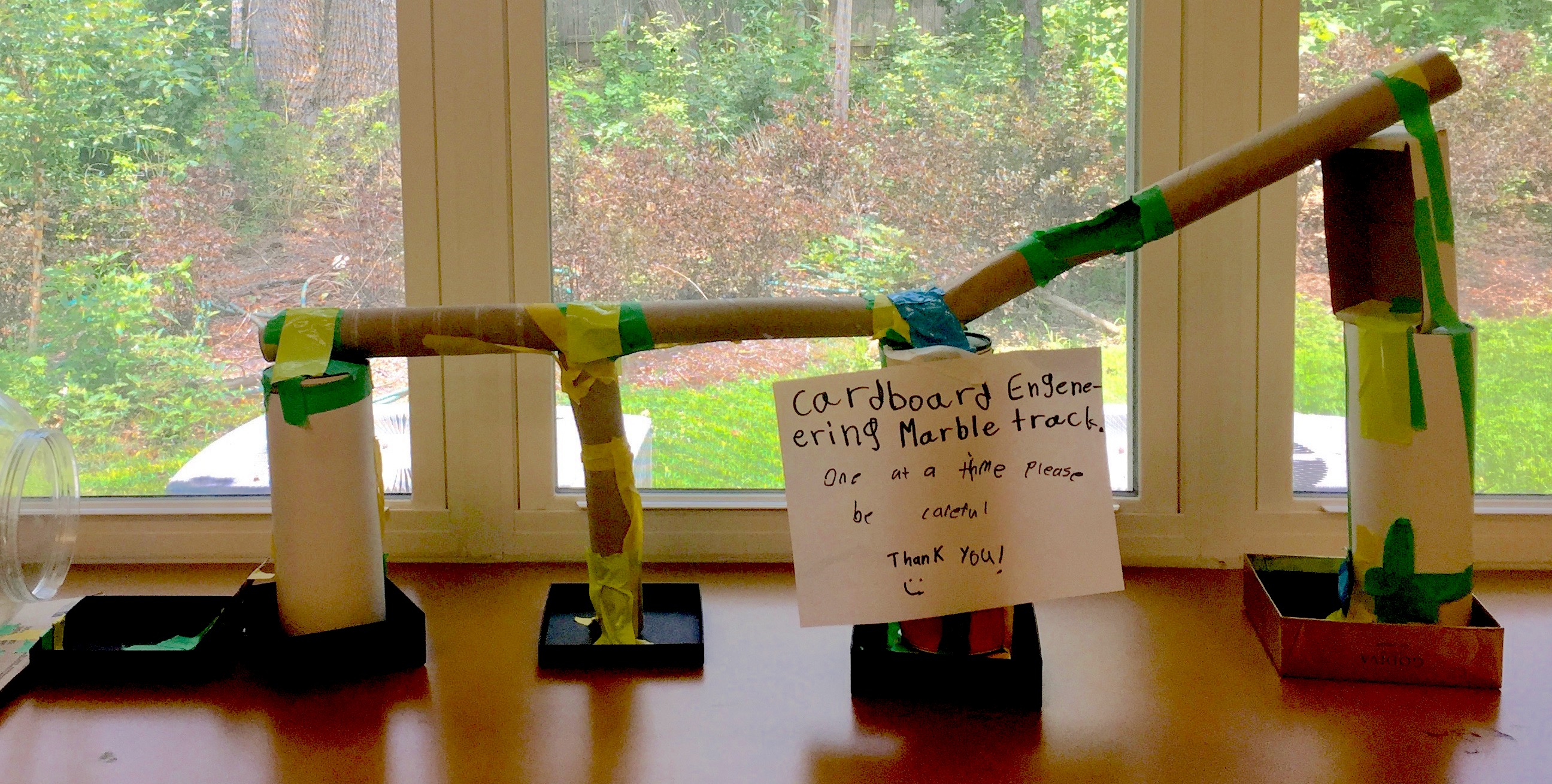

With just five half days to work together I decided that the Kindergarten-2nd graders would only use scissors to cut cardboard but would offer the 3rd-5th graders Klever Kutters, a safer alternative to a typical box cutter. I gave them a safety lesson on holding the cardboard with one hand while pulling the cutter through the it with the other—away from the holding hand.

The children mostly used scissors instead of the cutters. They preferred the less-sharp familiar tool. Initially I thought younger children would only use cereal box type cardboard, keeping the corrugated cardboard for older children. All ages impressed me with their willingness to work hard to shape corrugated cardboard.

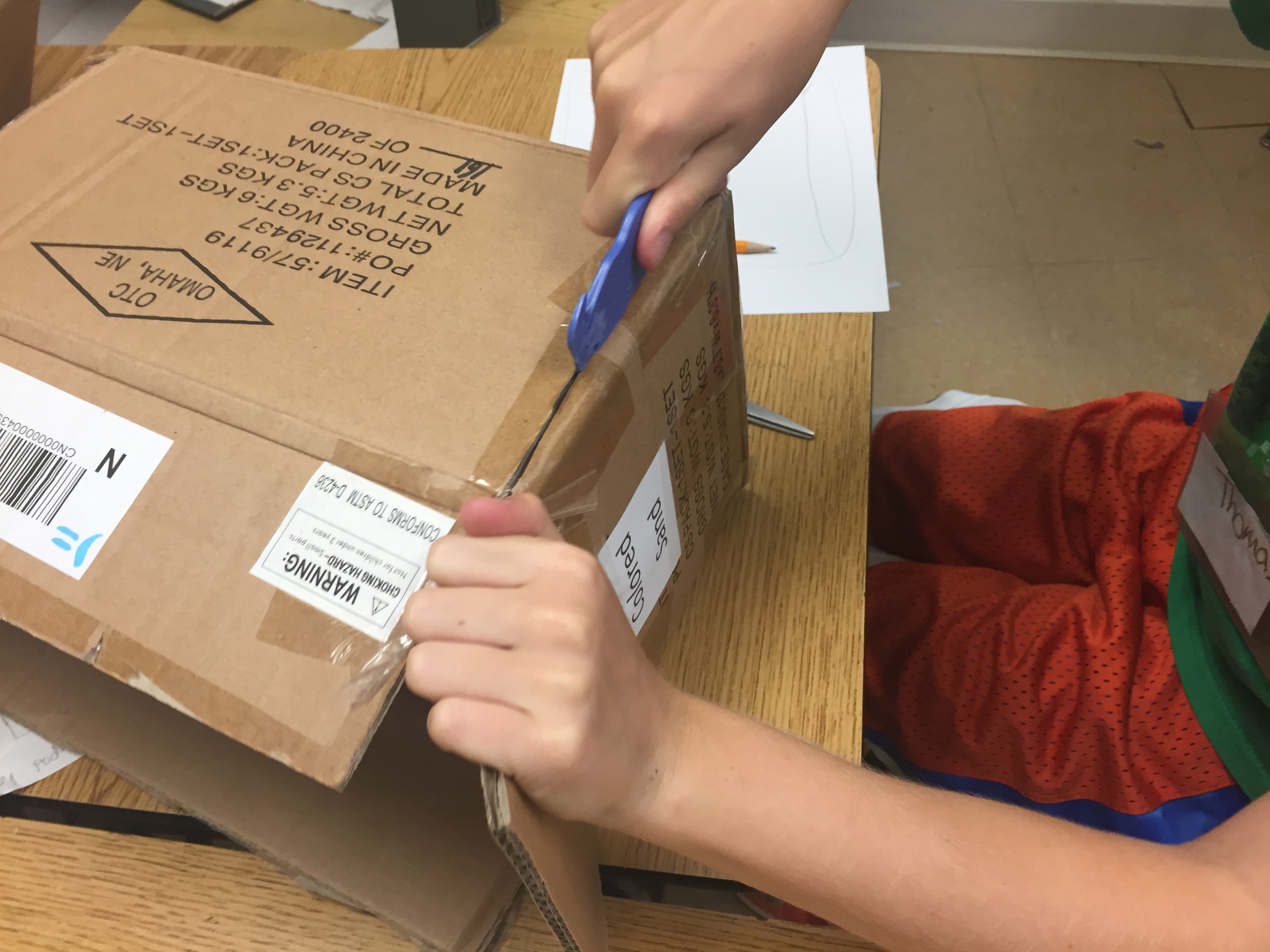

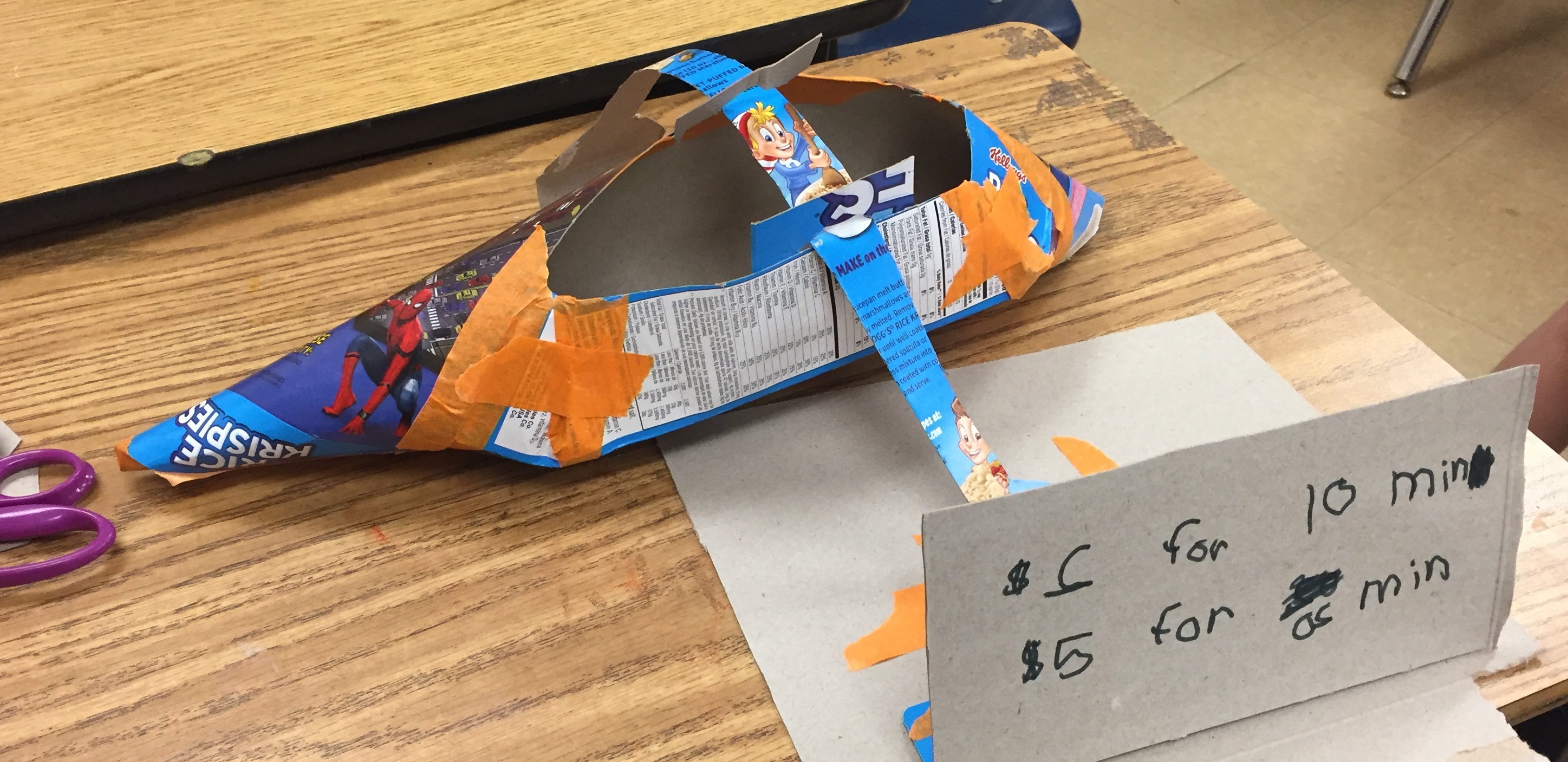

The project of making “something” using cardboard gave children an open-ended challenge. Miniature stage scenes, cozy kitty boxes, arcade games, a model kayak, figure with movable limbs, and a fort were structures designed and built, but not perfected over the week.

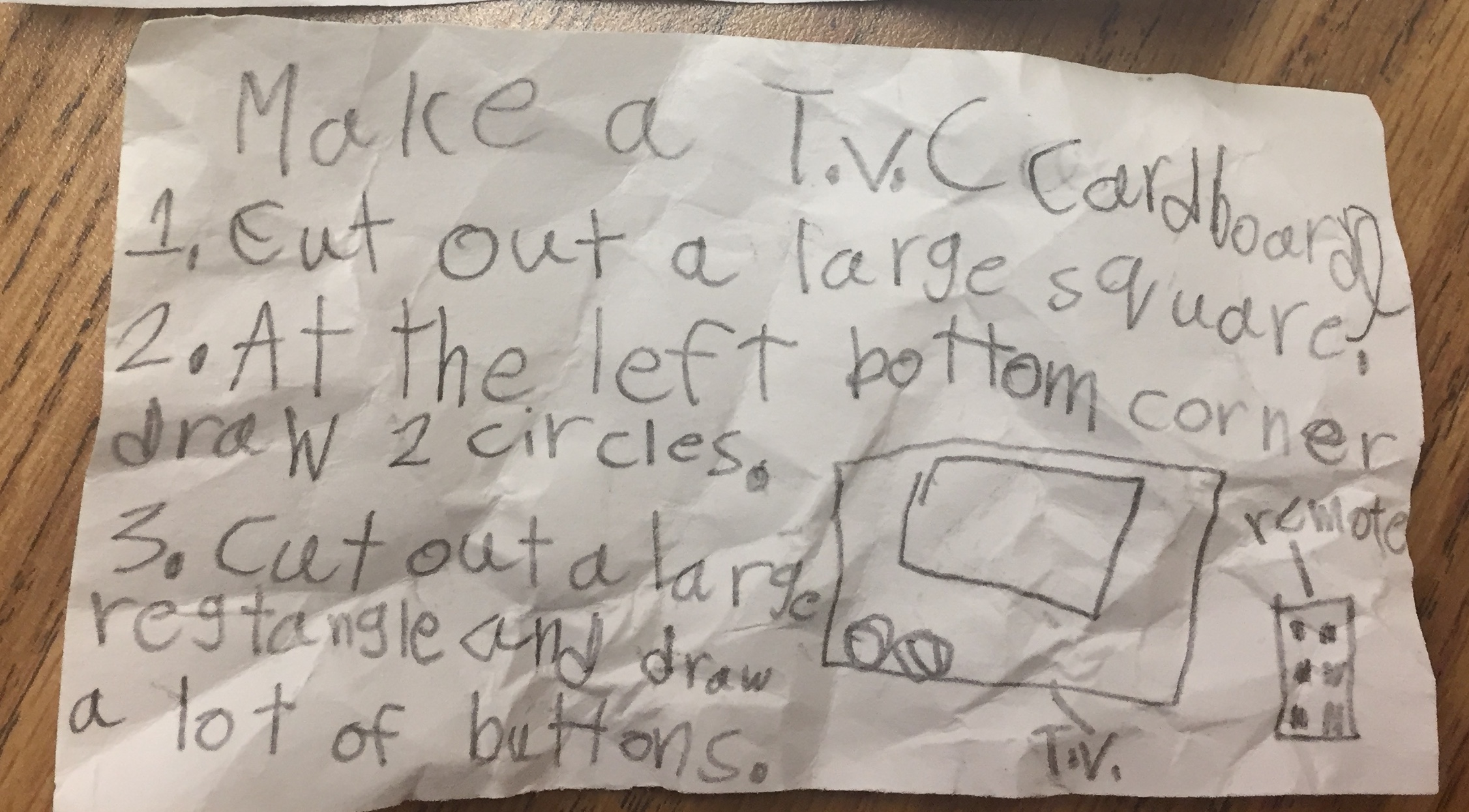

On the fourth day I challenged the older children to design and build for another person. Each child wrote a note describing and/or drew a picture of an object or structure they would like someone else to build for them. The papers went into a bowl and then each child drew one out to work on. This is when children’s communication and attention to ethical considerations were evident. They had to interpret the notes to meet the needs of their “clients.”

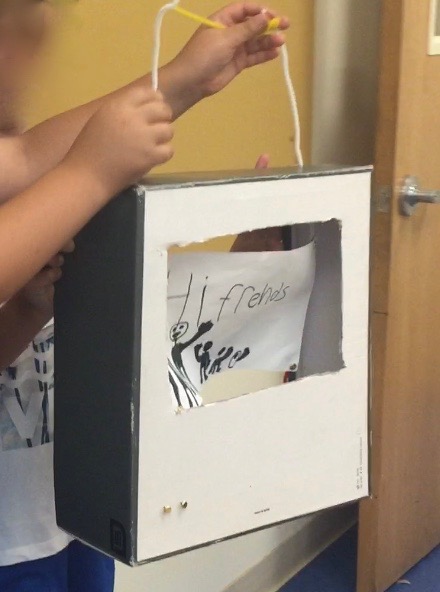

One child’s request detailed a television with remote. The engineer interpreted the design to include a moveable image to appear when the TV was “turned on.” In presenting the requested designed object to the clients the engineers demonstrated the features and discussed how the notes guided their design decisions. The children accepting the designed objects impressed me with their gracious appreciation for the work of their peers.

A classroom center for design using cardboard would provide opportunities for children to continue working on their ideas and solving problems through re-design during the school year. What do your children create with cardboard?

Engineering Habits of Mind. From STEM Learning with Young Children: Inquiry Teaching with Ramps and Pathways by S. Counsell, L. Escalada, R. Geiken, M. Sander, J.Uhlenberg, B. Van Meeteren, S.Yoshizawa, B. Zan. 2015. New York: Teachers College Press.

National Research Council (NRC). 2012. A Framework for K-12 Science Education: Practices, Crosscutting Concepts, and Core Ideas. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13165

In the October 201

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2019-10-13

A shared reading experience is one of the most powerful strategies for building children’s literacy skills according to the International Library Association (ILA pg 3) and in my experience as a reader, educator, and parent. Once a week I am a guest reader in a preschool classroom for four-year-olds. We stop and discuss the action as I read a library book (my favorite form of media!) and the children access, analyze, and interpret the images in the book. They are developing their ability to understand the book’s symbols and messages, building their literacy skills with support from their teachers and guest readers. I’ve been surprised that many times children identify a dog in a story as a wolf, even though I’m sure they have had many more first-hand experiences with dogs than with wolves.

Literacy is “the ability to identify, understand, interpret, create, compute, and communicate using visual, audible, and digital materials across disciplines and in any context” (ILA Literacy Glossary). The word can refer to basic knowledge in a specific activity, as in “media literacy,” rather than only to reading and writing. Media literacy is “the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, create, and act using all forms of communication,” and “media” is “all electronic or digital means and print or artistic visuals used to transmit messages” (NAMLE). National Media Literacy Week is October 21-25, 2019, a good time to share resources with families.

The word “create” represents a big part of literacy learning in early childhood. Children are more than consumers of media—they are creators of messages using drawn and written symbols, and those made with manipulatives, and on digital media. The imaginative play and dance, and the songs they choose to sing, are all messages about their interests, experiences, and understanding about the world.

The National Association for Media Literacy Education (NAMLE) offers resources for understanding how the media we use and create can be analyzed. In discussions with children about books, science experiences, and the community, we can ask, “What do you think happened and what do you think about it? NAMLE recommends asking:

These questions help young children reflect on media they create, and consider the perspectives of other people.

There is overlap between science literacy and media literacy—they both require us to provide evidence for our claims. Asking for and presenting evidence for how we know something is another way to help children understand the importance of media literacy and is central to the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) Practices of Science and Engineering and the Crosscutting Concepts. Young children’s evidence comes from their first hand observation and documentation of their experiences, or information from their family or learned from media. When I question why the children identified the animal as a wolf, they tell me their evidence, “It has teeth,” and “It looks like a wolf.” Of course they are right! I need to introduce the idea of animal behavior and many more images to help them distinguish between these animals when they occur in a book.

When children confidently make a declaration such as, “That’s a snake!” when you know it is an earthworm, you can ask for evidence. “What makes you think it’s a snake?” “I’m wondering how you know it is a snake?” “What about the way it looks or moves tells you it is a snake?” “Are there any ways it is different from a snake? How?” “Let’s look at some pictures of this animal and some snakes so we can compare them,” and “Where should we look?”

Encourage children to document their observations with drawings, photography, audio recording, and other media. Ask them, “What do you want people to learn about this animal from your drawing (size, body structure, habitat…)?” “How will you show it so they understand that?” Over time children will begin to consider these questions themselves and revise their drawings.

Resources

Ashbrook, Peggy. 2018. The Early Years, Analyzing Media Representations of Animals. Science and Children. 56(4): 16-17. https://www.nsta.org/publications/browse_journals.aspx?action=issue&thetype=all&id=116132

International Literacy Association (ILA). (2018). What effective pre-k literacy instruction looks like [Literacy leadership brief]. Newark, DE: Author. https://literacyworldwide.org/docs/default-source/where-we-stand/ila-what-effective-pre-k-literacy-instruction-looks-like.pdf?sfvrsn=817ba48e_8

International Literacy Association (ILA), Literacy Glossary. Retrieved October 2019 from https://literacyworldwide.org/get-resources/literacy-glossary

National Association for Media Literacy Education. (2007, November). Core principles of media literacy education in the United States. Retrieved October 2019 from http://namle.net/publications/core-principles

National Association for Media Literacy Education and Trend Micro, Inc. Building Healthy Relationships w/ Media: A Parent’s Guide to Media Literacy. Retrieved October 2019 from https://namle.net/a-parents-guide/

NGSS Lead States. 2013. Next Generation Science Standards: For states, by states. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. www.nextgenscience.org/next-generation-science-standards

A shared reading experience is one of the most powerful strategies for building children’s literacy skills according to the International Library Association (ILA pg 3) and in my experience as a reader, educator, and parent. Once a week I am a guest reader in a preschool classroom for four-year-olds. We stop and discuss the action as I read a library book (my favorite form of media!) and the children access, analyze, and interpret the images in the book.

By Sharon Delesbore

Posted on 2019-10-11

I am a first-year teacher at a high school listed as a priority to the district (i.e. school improvement needed). I like the school and the students but it seems like the administration is in my classroom all the time. I’m concerned that they do not trust my capabilities to teach my students. Am I being paranoid?

—C., Texas

Yes, you are being “watched” for lack of a better term. In any organization, administrators monitor the activity taking place. For schools, this monitoring happens during classroom walkthroughs. These walkthroughs help administrators connect to our students’ learning. As a first year teacher, it is even more important that your administration sees what is taking place in your classroom—not in an “I caught you” way, but to better assist you as you develop your instructional identity. A 2013 article in Educational Leadership, “How Do Principals Really Improve Schools?,” asserts that classroom walkthroughs allow for “a new pair of eyes in the classroom, where we are able to help a teacher become aware of unintended instructional or classroom management patterns. We could express appreciation for the wonderful work a teacher was doing because we had witnessed it firsthand. We observed powerful instructional strategies that we were able to share with other teachers.”

Administrators’ walkthroughs are opportunities for them to provide instructional leadership and coaching with specific feedback. Don’t be discouraged by the visits! Embrace the attention, demonstrate your abilities, and be open to the feedback as you strengthen your instructional identity.

I am a first-year teacher at a high school listed as a priority to the district (i.e. school improvement needed). I like the school and the students but it seems like the administration is in my classroom all the time. I’m concerned that they do not trust my capabilities to teach my students. Am I being paranoid?

—C., Texas

By Claire Reinburg

Posted on 2019-10-10

NSTA Press book authors will lead workshops at NSTA fall conferences around the U.S. Join us for these professional learning opportunities in Salt Lake City, Cincinnati, or Seattle.

Salt Palace Convention Center – Room 155B

Thursday, October 24, 2019

8:00–9:00 am Argument-Driven Inquiry in the Life, Physical, and Earth/Space Sciences: Lab Investigations for Grades 6–8 – Jonathan Grooms

12:30–1:30 pm One Teacher’s Influence on a Natural Phenomenon – Steve Rich

2:00–3:00 pm Argument-Driven Inquiry in Grades 3–5: Three-Dimensional Investigations That Integrate Literacy and Mathematics – Jonathan Grooms

3:30–4:30 pm Solar Science Provides Three-Dimensional Learning Experiences About the Sun, Earth, and Moon – Dennis Schatz

Friday, October 25, 2019

8:00–9:00 am Eureka! K–2 and 3–5 Science Activities and Stories – Donna Farland-Smith

9:30–10:30 am Argument-Driven Inquiry in Biology, Chemistry, and Physics: Lab Investigations for Grades 9–12 – Jonathan Grooms

12:30–1:30 pm Second Edition Curriculum Topic Study (CTS), a Systematic Process for Informing Curricular and Instructional Decisions – Joyce Tugel and Page Keeley

Saturday, October 26, 2019

8:00–9:00 am Uncovering K–12 Ideas About Matter and Energy Using Everyday Phenomena – Page Keeley

9:30–10:30 am Need Money? Write a Grant! – Patty McGinnis

11:00 am – 12:00 pm Developing and Using 3-D Formative Assessment Probes – Page Keeley

Duke Energy Convention Center, Junior Ballroom A (unless otherwise noted)

Thursday, November 14, 2019

8:00–9:00 am Argument-Driven Inquiry in Biology, Chemistry, and Physics: Lab Investigations for Grades 9-12 – Leeanne Gleim

12:30–1:30 pm Uncovering Student Ideas in Science and K–12 Language Literacy – Page Keeley and Joyce Tugel

2:00–3:00 pm Solar Science Provides Three-Dimensional Learning Experiences About the Sun, Earth, and Moon – Dennis Schatz

3:30–4:30 pm Eureka! K–2 and Grades 3–5 Science Activities and Stories – Donna Farland-Smith

5:00–6:00 pm Never Stop Wondering – Emily Morgan

Friday, November 15, 2019

8:00–9:00 am Developing and Using 3-D Formative Assessment Probes – Page Keeley

8:00–9:00 am Reading, Writing, and Reasoning in the School Yard – Steve Rich (Hyatt Regency, Buckeye B)

9:30–10:30 am Picture-Perfect Science Lessons: Using Children’s Books to Guide Inquiry, K–5 – Emily Morgan and Karen Ansberry

11:00 am – 12:00 pm It’s Still Debatable…and Elementary! Using Socioscientific Issues to Develop Scientific Literacy, K–5 – Sami Kahn

11:00 am – 12:00 pm Second Edition Curriculum Topic Study (CTS), a Systematic Process for Informing Curricular and Instructional Decisions – Joyce Tugel and Page Keeley (Hyatt Regency, Bluegrass A)

2:00–3:00 pm Argument-Driven Inquiry in the Life, Physical, and Earth-Space Sciences: Lab Investigations for Grades 6–8 – Leeanne Gleim

2:00–3:00 pm Next Time You See a Bee – Emily Morgan (Conv. Ctr. 203/204)

Saturday, November 16, 2019

8:00–9:00 am Picture-Perfect STEM Lessons: Using Children’s Books to Inspire STEM Learning,K-5 – Emily Morgan and Karen Ansberry

9:30–10:30 am NSTA Best Sellers Notable Notebooks and Exemplary Evidence with Eureka! – Donna Farland-Smith and Jessica Fries-Gaither

11:00 am – 12:00 pm Argument-Driven Inquiry in Grades 3–5: Three-Dimensional Investigations That Integrate Literacy and Mathematics – Leeanne Gleim

Washington State Convention Center, Room 615-617 (unless otherwise noted)

Thursday, December 12, 2019

8:00–9:00 am Reading, Writing, and Reasoning in the School Yard – Steve Rich

12:30–1:30 pm Argument-Driven Inquiry in Grades 3–5: Three-Dimensional Investigations That Integrate Literacy and Mathematics – Victor Sampson

12:30–1:30 pm Uncovering Students’ (and Teachers’) Ideas About Engineering and Technology – Page Keeley, Mihir Ravel, and Cary Sneider (Room 620)

2:00–3:00 pm Science Curriculum Topic Study: Connecting Scientific Practices, Core Ideas, and Crosscutting Concepts – Page Keeley

3:30–4:30 pm Picture-Perfect STEM Lessons: Using Children’s Books to Inspire STEM Learning, K–5 – Emily Morgan

3:30–4:30 pm Fact or Phony? Successful Strategies to Promote Media Literacy – Laura Tucker and Lois Sherwood (Room 2B)

Friday, December 13, 2019

8:00–9:00 am Next Time You See a Bee – Emily Morgan

9:30–10:30 am Developing and Using 3-D Formative Assessment Probes – Page Keeley

11:00 am – 12:00 pm Solar Science Provides Three-Dimensional LearningExperiences About the Sun, Earth, and Moon – Dennis Schatz

2:00–3:00 pm Eureka! K–2 and Grades 3–5 Science Activities and Stories – Donna Farland-Smith

2:00–3:00 pm Argument-Driven Inquiry in the Life, Physical, and Earth-Space Sciences: Lab Investigations for Grades 6–8 – Victor Sampson (Room 3B)

Saturday, December 14, 2019

8:00–9:00 am Argument-Driven Inquiry in Biology, Chemistry, and Physics: Lab Investigations for Grades 9–12 – Victor Sampson

9:30–10:30 am Instructional Sequence Matters, Grades 3-5 – Patrick Brown

11:00 am – 12:00 pm What Is the Difference Between Weather and Climate? – Laura Tucker

11:00 am – 12:00 pm Never Stop Wondering –Emily Morgan (Room 4C-3)

NSTA Press book authors will lead workshops at NSTA fall conferences around the U.S.

By NSTA Web Director

Posted on 2019-10-04

Lori Nelson is committed to STEM education through her classroom instruction, applying for grants, pursuing professional development, creating school STEM events, and sharing ideas with other teachers. She is the sponsor of the Chaffee Greenpower Engineering Team and a lead teacher for the Project Lead the Way engineering program. In 2011 Nelson created Chaffeetopia, an annual STEM festival, which is a space-themed event featuring hands-on science and engineering activities. In 2012 she collaborated with a NASA engineer to create an annual, weeklong curriculum to teach students how to build and launch rockets. Nelson has presented several sessions at the Alabama Science Teachers Association annual conference, the National Science Teachers Association annual conference, and the Space Port Area Conference for Educators. She has received several awards for science education, including the National Science Teachers Association Maitland Simmons Award, the Air Force State Teacher of the Year, the Alabama Science Teachers Association Elementary Science Teacher of the Year, and the National Space Club Educator of the Year. Parent Meghan Nester says, “One of the things that is most impressive to me about Mrs. Nelson, actually happens outside of the classroom. She tirelessly works to expand her own knowledge base and continually have more to offer her students. From summer camps and conferences, to developing a network of local connections that can add to her students’ learning experience, Mrs. Nelson is a true example of a lifelong learner.”

Visit the NSTA website for more information on the Sylvia Shugrue Award for Elementary School Teachers.

By NSTA Web Director

Posted on 2019-10-04

As a teacher in Philadelphia, the most significant obstacle that Jayda Pugliese has encountered is the lack of resources due to budget constraints. When she arrived at her current school as a fifth-grade science and mathematics teacher, there were no science books or materials for grades K–6. She overcame this obstacle by writing for competitive grants and obtained over $20,000 for various science-based initiatives, such as a rooftop garden and materials for the school (textbooks, microscopes, glassware). She also wrote and received a grant that helped place fully stocked Chromebook carts in ten classrooms to incorporate more technology. Concetta D’Alessandro, School-Based Teacher Leader at Andrew Jackson Elementary School, says Pugliese “has broadened my perspective as an educator because of her extensive involvement with the school and her passion to make science accessible to both the students and the community.” Pugliese also raised money for a MakerBot 3D Printer, which has allowed students to build and donate a usable, prosthetic hand for a four-year-old girl within the community. Currently, her students are creating a prosthetic leg for a dog in Connecticut. These experiences have allowed Pugliese to turn her science instruction into service learning projects, which has made a significant difference in the level of motivation and tolerance among her students. They are changing the world right from the classroom.

Visit the NSTA website to learn more about the Sylvia Shugrue Award for Elementary School Teachers.

By Carole Hayward

Posted on 2019-10-02

Fans of Oprah Winfrey know the phrase, “When you know better, you do better.” And now Page Keeley and Joyce Tugel, authors of Science Curriculum Topic Study, 2nd Edition—Bridging the Gap Between Three-Dimensional Standards, Research, and Practice, are offering the perfect way for science teachers to know better and do better. In the first national workshop for Science Curriculum Topic Study, in Des Moines Iowa, on October 8, they’ll introduce participants to the new, updated Curriculum Topic Study (CTS) tools and processes for linking disciplinary content, scientific and engineering practices, and crosscutting concepts to research on learning and teacher practice.

Bring a team and learn how to use CTS as a teacher or leader.

CTS has been called the “missing link” between science standards, teacher practice, and improved student achievement. It begins with questions that help you center your teaching. For instance:

Much of the workshop will be based on the NSTA Press book Science Curriculum Topic Study, 2nd Edition—Bridging the Gap Between Three-Dimensional Standards, Research, and Practice, which is newly mapped to the Framework for K–12 Science Education and the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), and updated with new standards and research-based resources. Attendees will learn to make the shifts needed to reflect current practices in curriculum, instruction, and assessment. The methodical study process used will help educators intertwine content, practices, and crosscutting concepts.

What will the Science CTS do for your school?

Why will the Science Curriculum Topic Study Workshop be a game changer for you? In the words of Nevada science teacher Gail B: “I wish I’d had this years ago! It took all the work out of looking up standards and how to apply them to students.” Just a few of the ways schools and districts change what they’re doing right away include:

This standards- and research-based versatile process can be used by individuals or professional learning groups and supports implementation of any two- or three-dimensional standards, including the NGSS.

A follow-up web seminar, to be scheduled after the workshop, will support participants as they use CTS in their district or professional learning setting.

All participants will receive:

Meet the Presenters

Best-selling authors Page Keeley and Joyce Tugel will be there to guide learning, share insights, and answer questions. Page and Joyce have been science education colleagues and professional development partners for two decades, and they worked together on the original NSF-funded Curriculum Topic Study (CTS) project. As Page developed the first CTS process and authored the first edition, Joyce was instrumental in field testing and implementing the CTS professional development designs.

Your Path to Success Starts Here

By Debra Shapiro

Posted on 2019-10-02

“It is important for elementary students to learn about agriculture because there is a lot of illiteracy when it comes to agriculture. Social media is a main contributor to ag-illiteracy because there are a lot of negative social media campaigns out there…No one looks at the science-based facts, but instead [they believe] what they read,” contends high school student Katelyn Young, vice president of the Arcadia Valley Career Technology Center Future Farmers of America (FFA) Chapter in Ironton, Missouri. She earned certification to teach third graders the Ag-Ed on the Move curriculum (see www.agmoves.com) from Missouri Farmers Care, an organization promoting the continued growth of Missouri agriculture and rural communities.

Young says it’s crucial “to push that positive message across to students who don’t know much about agriculture. These kids are three to five generations removed from the farm. Elementary school is such an important learning time for kids, so what better time to teach them about agriculture? These kids are growing up in a world where the population will be [more than] nine billion in the year 2050. It will be these kids’ job to figure out how to feed the growing world.”

“Almost everything we do is related to food,…[and students need to know that] agriculture careers involve more than just farming,” maintains retired teacher Darleen Horton of Louisville, Kentucky, who contributed lessons to the book Ready, Set, Grow: A Kentucky Educator’s Guide to School Gardens and Hands-On STEAM Learning (available free at www.kyreadysetgrow.org). “Some agriculture jobs are lab jobs,” she points out, while some “involve food already grown,” such as restaurant jobs and careers “connected with the business end of food.” She adds, “Students need to understand the economics of farming, such as gas costs,…and natural ways to garden that help the environment.”

Horton notes that “elementary students embrace what you teach them” and what they learn “can impact their families, who can [be inspired by young students to] learn to recycle and grow plants and food.”

“There’s not a lot of food grown in North Texas, and we’re in the city,… [so] students don’t understand food production,” says Kim Aman, retired teacher and now program director of Moss Haven Farm, located at Moss Haven Elementary School in Dallas, in the Richardson Independent School District. It’s important to reach elementary students because “they will be the future policy makers, shoppers, and buyers,” she asserts.

In addition, agriculture connects with topics like healthy eating. “There are 10-year-olds who already have type 2 diabetes,” Aman points out, so teaching agriculture to young students could positively affect their health. Aman has written related preK–5 curriculum for the American Heart Association and Whole Kids Foundation.

“Some students are scared [initially about farm work]. Some are afraid to get their hands dirty, or to eat radishes, or to be near bees,” Aman relates. She helps them overcome their fears, especially of bees. “I teach them not to be scared of bees and how to act around them.” Most students, she notes, “are pretty interested [in agriculture] because it’s novel to them; they don’t get outside much.” And for students who struggle in school, “digging up worms and growing plants levels the playing field for them.”

Tara Kristoff, curriculum director for Rock Falls School District 13 in Rock Falls, Illinois, partnered with local farm bureaus for teacher professional development in agriculture and resources for students. In her prior school district, where she was a curriculum director, teachers initially weren’t receptive to teaching about agriculture.

“We had representatives from the [Cook County Farm Bureau] show our teachers…how they can link trade books with science and social studies to teach agriculture,” says Kristoff. “[Teachers] understand the science of growing corn and soybeans, but with literature [added], they really get enthusiastic” because they can teach it in their English language arts block.

“For example, our fourth-grade teachers taught a unit on pigs. The students learned that Illinois is a major producer of pork as a staple economy globally, and the importance of raising pigs for food. Then the students read Charlotte’s Web to wrestle with the ethical dilemma [of] raising pigs for food versus a pet. Lastly, the students went for a tour of a pig-raising farm at Fair Oaks Farms in Indiana, where experts explained [how] the life cycle of the pig [relates] to our economy,” Kristoff recalls.

Teaching students that animals can be food sources requires “a delicate balance,” she observes. Younger students simply learn that “we grow pigs in Illinois,” while third and fourth graders discover that “pork is a staple and pigs are part of our food system. The things students eat—pork tamales and bacon, for example—they [learn to] associate with pigs. They understand they’ve been eating it; they just hadn’t realized it,” Kristoff explains.

“In Illinois, agriculture is the most important job, our main source of income and revenue,” she contends. Noting her current school district has 80% of residents living in poverty, she asserts, “It is especially important for me as a director of curriculum to have students understand where their food truly comes from as well as consider agriculture/agribusiness as a future career.”

“I have been incorporating agriculture fairly heavily [over] the past three years,” says Nancy Smith, first-grade teacher at Bentwood Elementary in Overland Park, Kansas. Smith says she finds it easy to blend agriculture with science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM), and she starts the school year by teaching “about careers in agriculture and STEM as part of my Labor Day lessons.” Later on, “we talk about farmers’ tools, the axe, the trowel, and the shovel” as part of a STEM lesson.

For her school’s student and family night this year, she will incorporate agriculture throughout the event. “The stations will be all agriculture-related. [For example,] Kansas Corn [an organization comprised of the Kansas Corn Growers Association and the Kansas Corn Commission] will have a station. [Students from all grade levels and their families] will learn about Kansas agriculture and do hands-on activities,” she relates.

“I invited a farmer who uses drones to examine his crops. He will demonstrate his drones at the event and explain why he uses them,” she reports.

When she can’t bring students to a farm, Smith takes them on virtual field trips to farms. She also invites high school students from the local FFA chapter “to design activities and centers for my students. This has an impact on the high school students as well,” she observes.

To prepare to celebrate the state holiday Kansas Day ( January 29, the day Kansas was admitted to the United States), Smith will have her students spend a week researching a school lunch that will feature ingredients produced on Kansas farms. “I’ll have farmers and grocery store employees come in,” she relates. “The students will look at the nutritional values and costs of the food. They’ll pitch [their menu] to the food service workers at our school [and ask them] to serve it next year.”

This article originally appeared in the October 2019 issue of NSTA Reports, the member newspaper of the National Science Teachers Association. Each month, NSTA members receive NSTA Reports, featuring news on science education, the association, and more. Not a member? Learn how NSTA can help you become the best teacher of science you can be.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

By Debra Shapiro

Posted on 2019-10-02

After learning about fire dynamics— how fires start, spread, and develop— and doing hands-on activities with firefighters, eighth graders in Georgia’s Cobb County School District solve a virtual fire-related crime with help from an arson investigator as part of a partnership involving the district’s middle schools, the Cobb County Fire Department, and Underwriters Laboratories (UL). UL offers a free module that the district’s eighth-grade science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) teachers use, Fire Forensics: Claims and Evidence, on its Xplorlabs online learning platform (see the unit at http://bit.ly/2lKh81k). “I saw [UL staff] at an NSTA conference and heard about UL’s fire dynamics curriculum,” recalls Sally Creel, the district’s STEM and innovation supervisor. “Our goal is to put students in contact with [workers] in STEM fields,” so partnering with UL and the fire department has helped provide students with authentic STEM learning, she observes.

“We don’t get a lot of kids wanting to fight fires,” says Sean Gray, Cobb County Fire Department captain and a member of the UL Firefighter Safety Research Institute’s Advisory Board. By exposing students to the UL curriculum and the roles of fire service professionals, “we hope they will be interested [in a fire service career] and stay with the community if they’re not going on to college,” he explains, adding that “the middle level is an important time to reach kids.”

Students experience “the excitement of having firefighters in their classroom,” says Creel. “The firefighters come in uniform, and we make sure to have a diverse group of firefighters” so all students can relate to the material. “The program is authentic and memorable,” she maintains.

Firefighters co-teach the lessons with teachers, and they train together to use the curriculum. “We’ve now trained 80 firefighters and 50 to 60 teachers at the middle and high school levels,” Gray reports.

The UL curriculum “is set up as a scenario, as in problem-based learning. Students have to discover what happened: an accident or arson,” Creel explains. The material also supports the Next Generation Science Standards and three-dimensional learning because it “integrates science and engineering practices, doing research and digging into data to determine what happened,” she points out. “Fire and how it behaves [serves as] the phenomenon, and students draw conclusions based on data and UL research.”

Michael Stecher, science teacher, and Amber Schick, English language artsteacher at Liberty Middle School (LMS) in Fargo, North Dakota, have served as team advisors for students competing in eCYBERMISSION, a web-based STEM competition for students in grades 6–9 sponsored by the U.S. Army Educational Outreach Program and administered by NSTA (www.ecybermission.com). As part of eCYBERMISSION, students identify community problems and explore science explanations and engineering solutions. This year, one LMS team focused on kitchen fires. “They realized most kitchen fires are grease fires,” says Stecher, and after polling other students about how they would extinguish those fires, “most students said they would put water on the grease fire,” which makes the fire worse. The team decided “an awareness campaign and a device was needed,” he relates.

The teachers helped the team research what products extinguish grease fires. Their first proposed prototype was a pan equipped with a device “that had a button you could press to make sand come out and put out the fire,” Stecher recalls. After further research, the team “decided that a small blanket could be [thrown over] a pan and put out the fire because it eliminated oxygen,” he reports.

Working with the West Fargo Fire Department in a controlled environment outdoors, the students tested four prototypes on a pan of burning vegetable oil to determine whether the blanket should contain sand, baking soda, or salt or if a blanket containing nothing would do the job. The students learned that baking soda and sand worked best, and the blanket containing nothing “was the worst because it didn’t have the weight to put out the fire,” says Stecher.

Schick notes that the students wanted their blanket to be reusable, but they learned “the material wasn’t flame retardant, so [the blanket] couldn’t be reused.”

The project “gave students an understanding of how to do science and how to test [prototypes] as part of the engineering design process,” Stecher maintains. “It was meaningful to them because lives could be saved, and [it provided] a community tie-in with the West Fargo Fire Department. It brought science to life in my class.”

Doing projects like this one “gives research meaning, why it’s important to research and understand the problem,” Schick contends. The project “gave them skills and expertise and was an authentic learning piece, more than just writing a paper. The students were excited and passionate, and there was 100% integration with my subject— the best way to do research.”

Wilson High School in Los Angeles, California, offers a Firefighter Academy Magnet in collaboration with the Los Angeles City Fire Department (LAFD) for students interested in learning about a career in fire service and emergency response. As part of the magnet, chemistry teacher Deborah Wang teaches Firefighting Technology, a course covering science, technology, and research with a focus on firefighting. “It’s nice to integrate occupations like firefighters. It can bring more interest and relevance to students,” she observes.

The course is open to all Wilson students. “Some students want to learn more about [firefighting] careers; others take it as an elective requirement,” Wang explains.

Firefighting Technology also covers engineering, history, architecture, and philosophy; “it’s an interdisciplinary study through a firefighting lens,” says Wang. Her students learn about architecture by studying building codes and determining whether they comply with fire codes. “We mapped our school’s building plan [and wondered] how we could get water to the fourth or fifth floor,” Wang recalls.

Students learn “the history of how [firefighting] technology has progressed. [Firefighters] used to have only water and buckets, then fire extinguishers,” Wang relates. During World Wars I and II, firefighters “learned that carbon tetrachloride was not good to use in fire extinguishers because it damages the lungs…Now there are high-tech fire extinguishers with less harmful chemicals.”

She continues, “Because we work with the [LAFD], they give us uniforms and field trips…[For example,] I took my ninth graders to the [LAFD] Museum last year. It [gave them] background for my class [when they saw] the museum’s artifacts.” Her students also worked with the LAFD to do a fire inspection.

The firefighter magnet is valuable, according to Wang, because “the field for first responders and firefighters is really rigorous. Having more candidates who are better prepared is important for the field’s future and the safety of our communities.”

This article originally appeared in the October 2019 issue of NSTA Reports, the member newspaper of the National Science Teachers Association. Each month, NSTA members receive NSTA Reports, featuring news on science education, the association, and more. Not a member? Learn how NSTA can help you become the best teacher of science you can be.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA