NSTA’s K-College March 2016 Science Education Journals Online

By Korei Martin

Posted on 2016-03-01

Looking to show your students the connections between plants, animals, and the environment? Want in-depth activities to explain physical science concepts to your middle school students? Are your students interested in how solar energy works? Are you curious about connecting intermolecular forces to real world phenomena using a concept-building activity? The March K–College journals from the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) have the answers you need. Written by science teachers for science teachers, these peer-reviewed journals are targeted to your teaching level and are packed with lesson plans, expert advice, and ideas for using whatever time/space you have available. Browse the March issues; they are online (see below), in members’ mailboxes, and ready to inspire teachers!

It may be hard to see on first glance, but examples of human impacts on Earth are all around us. Through the activities in this issue, students will learn about ecology while gaining a deeper connection to plants, animals, and the environment.

Featured articles (please note, only those marked “free” are available to nonmembers without a fee):

- Aquaponics: What a Way to Grow!

- Capturing Insects and Student Interest

- Crabby Interactions

- Understanding Human Impact

- Free – Outstanding Science Trade Books for Students K–12

- Free – The Lorax Readers’ Theater

- Table of Contents

Seeing is believing—and it can also lead to understanding, as is the case when you use a thermal imaging camera to explore the concept of the conservation of energy. This is just one of the hands-on activities you’ll find in this issue that will help you explain physical science concepts to your middle level students.

Featured articles (please note, only those marked “free” are available to nonmembers without a fee):

- Build Your Own Sunglasses

- Chemical Connections: A Problem-Based Learning, STEM Experience

- Free – Editor’s Roundtable: Spreading the News—With Care!

- Exposing Hidden Energy Transfer With Inexpensive Thermal Imaging Cameras

- Outstanding Science Trade Books for Students K–12

- Free – What We Call Misconceptions May Be Necessary Stepping-Stones Toward Making Sense of the World

- Table of Contents

Solar energy is clean, free, and abundant worldwide. The challenge, however, is to convert it to useful forms that can reduce our reliance on fossil fuels. In this issue, the feature article “Powered by the Sun” presents an activity in which students learn firsthand how solar energy can be used to produce electricity specifically for transportation. The activity introduces students to solar-powered mass transit and challenges them to design their own solar vehicle. “Building a Greener Future,” another article using the engineering-design process, describes how students designed and built compost bins for a community garden. This issue also addresses partition coefficients in chemistry, using the starlet sea anemone in biological research, and the challenges posed by the language of science texts—and how to overcome them.

Featured articles (please note, only those marked “free” are available to nonmembers without a fee):

- Building a Greener Future

- Does It Mix?

- Free – Editor’s Corner: Write for the Science Teacher (part 2)

- Outstanding Science Trade Books for Students K–12

- Free– Powered by the Sun

- Science’s Super Star

- Table of Contents

Journal Of College Science Teaching

Read about a study that focused on connecting the abstract science concept of intermolecular forces to real-world phenomena using a concept-building activity. See the Research and Teaching article that examined the effect of a 6-week summer bridge program on STEM retention of targeted demographic groups. And be sure to read the Two-Year Community column article about an online Introduction Biology course desig

ned to follow the recommendations from the Vision and Change in Undergraduate Biology Education: A Call to Action report.

Featured articles (please note, only those marked “free” are available to nonmembers without a fee):

- Free – A Hands-On Activity to Build Mastery of Intermolecular Forces and Its Impacts on Student Learning

- An Interdisciplinary Approach to Success for Underrepresented Students in STEM

- Deliberative Pedagogy in a Nonmajors Biology Course: Active Learning That Promotes Student Engagement With Science Policy and Research

- Developing Student Presentation Skills in an Introductory-Level Chemistry Course With Audio Technology

- Research and Teaching: Association of Summer Bridge Program Outcomes With STEM Retention of Targeted Demographic Groups

- Research and Teaching: Undergraduate Science Students’ Attitudes Toward and Approaches to Scientific Reading and Writing

- Table of Contents

Get these journals in your mailbox as well as your inbox—become an NSTA member!

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

Feature

Bridging Neuroscience and Education Through Museum-School Partnerships

Connected Science Learning March 2016 (Volume 1, Issue 1)

By Dale McCreedy, Jayatri Das, and Julia Skolnik

The Franklin Institute provides programs that help educators of all disciplines understand the key ideas and recommendations for enhanced teaching practices based on new research from the field of neuroscience.

The connections among neuroscience, educational research, and teaching practice have historically been tenuous (Cameron and Chudler 2003; Devonshire and Dommett 2010). This is particularly true in public schools, where so many issues are competing for attention—state testing, school politics, financial constraints, lack of time, and demands from parents and the surrounding community. Teachers and administrators often struggle to make use of advances in educational research to impact teaching and learning (Hardiman and Denckla 2009; Devonshire and Dommett 2010). At the Franklin Institute, we have developed a model that integrates expertise in understanding and communicating research with teaching practice, supported by relevant science content and museum exhibits, to provide rich professional development (PD) opportunities for K–12 educators across disciplines. These programs help educators of all disciplines understand the key ideas and recommendations for enhanced teaching practices based on new research from the field of neuroscience. Evaluation results show that educators find high value in evidence-based information, strategies, and informal hands-on experiences that can be broadly applied to teaching across multiple subject areas and ages.

What We Know About the Brain

"This workshop has caused me to think more strongly about the relevancy of the things I teach and how I can keep my students engaged.” —K–6 music teacher

Although the past few decades have seen major advances in the neuroscience of learning, this emerging field continues to be underused in teacher preparation and continuing education (Pickering and Howard-Jones 2007; Devonshire and Dommett 2010). Although a sophisticated and updated understanding of how the brain works and changes over time is critical for educators as experts in teaching and learning, some common myths about the brain are unsettlingly pervasive. For example, the misconceptions that we use only a small percentage of our brain, or that one hemisphere of the brain is exclusively responsible for certain strengths such as creativity or problem solving (i.e., right-brained or left-brained), are widely believed to be true, even among educators (Howard-Jones 2014).

Established cognitive science research shows that active learning and building upon prior knowledge and experiences are essential for constructing advanced understanding (NRC 2000). Accessing prior knowledge also motivates youth to feel that their experiences are relevant. From a neuroscience perspective, making connections to long-term memory in the hippocampus enhances neural networks, which allows for better recall of old information and retention of new information (Eichenbaum 2000). In addition, emotional cues that trigger brain activity in the amygdala strengthen associated long-term memory storage in connected brain regions (Phelps 2006).

One of the most important advances in neuroscience with relevance to education is our greater understanding of brain development throughout the lifespan (Giedd et al. 1999; Huttenlocher and Dabholkar 1997). In childhood and adolescence, the brain progresses through critical periods of rapid growth of neurons and neuronal connections (synapses). This is followed by experience-dependent elimination of unnecessary synapses, known as synaptic pruning. In addition, we now know that the brain is always changing via synaptic plasticity, as synapses are continually modified throughout our lifetime (Wilson and Conyers 2013; May 2011). Connections that are used and revisited become stronger and faster, whereas those that remain unused weaken, leading to forgetting.

Program Design and Structure

Based on these critical concepts that bridge neuroscience and education, we created a set of museum- and school-based workshops (see sidebar) to support school districts that are interested in thinking about how brain-based learning can inform educational practice. The introductory workshop has been offered to K–12 teachers across all disciplines, including those from nonscience specialties (e.g., language arts, physical education, art, music, special education), administrators, and out-of-school and community-based educators in informal settings. It is sometimes a stand-alone workshop, but in many cases, it has been a first step to a continued districtwide relationship, as this model is designed to be flexible and can be customized according to the needs, strengths, and opportunities of each district.

Understanding the Brain, Part 1: Becoming a Learning Scientist

In this introductory workshop, we first debunk some of the commonly held misconceptions about the brain and focus on improving teachers’ understanding of the basics of brain function and development. This foundational science helps educators grasp that children’s brains are malleable and especially susceptible to long-lasting change during the toddler and teen years, when synaptic pruning is at its highest (Jensen and Nutt 2015).

I learned that we use 100% of our brain. The brain is very malleable, and we learn based off of our experiences. Intelligence is not a set number. —Eighth-grade teacher

Next, educators experience a unique element available at the Franklin Institute—the opportunity to explore Your Brain, an interactive exhibit that engages visitors in experiencing the many ways in which the brain functions (www.fi.edu/exhibit/your-brain). Visitors can see an actual preserved human brain, climb through simulated neural pathways, view scientific visualizations of human and animal brains, and experience how their brains process everyday life. This informal learning experience allows educators to explore their questions about the brain, ties in to the themes of the research-to-practice discussion, and inspires new ideas and questions to explore as a professional or with students.

I absolutely loved being able to explore the exhibit. Seeing how my brain reacted to different scenarios (as an adult) gave me perspective on how my students might react. —Sixth-grade teacher

Next, we apply these key ideas to three practical strategies for teaching and learning in the classroom. Tapping into existing experiences to build more sophisticated neural networks, providing active learning experiences that allow youth to use multiple regions of the brain, and creating opportunities to revisit and reinforce what students have learned are all effective methods of maximizing learning based on what we know about the brain.

My understanding of the brain improved, helping me to create more meaningful learning opportunities. —Fourth-grade teacher

[Learning about the brain] will allow me more freedom to incorporate more student centered learning. I can ‘bring back the fun’ to the classroom. —Fourth-grade teacher

Finally, we encourage educators to consider ways to shift to a culture of brain-based learning, influenced by the concept of growth mindset (Dweck 2007). In contrast to a fixed mindset—the idea that intelligence is genetically predetermined, stable from birth, and does not change over time—a growth mindset considers that intelligence can change based on life experiences and hard work. This concept complements the scientific evidence for synaptic plasticity. The growth-mindset approach is also particularly compelling for teachers because of its potential to promote persistence in helping students develop skills, both cognitive and noncognitive (such as grit and resilience) that are important for academic success. This is empowering for students as well, allowing them to focus on improving through rigorous practice and creative exploration rather than believing intelligence and the capacity to learn are inherent and unchangeable.

[The workshop] has taught me how important it is to have a growth mindset as well as teaching my students to do/have the same. —Fourth-grade special education teacher

Some of my strugglers started off the year shutting down, putting heads down and saying ‘I can’t do this…’ [In a recent conference] I was able to tell one parent how he had completely changed his mindset. He doesn’t say ‘I can’t do this’ anymore. He says, ‘This is kind of tricky, but I know I am going to work really hard on it.’ —Third-grade teacher

Parts 2 and 3: Applying and Extending Brain-Based Learning in the Classroom

Many administrators who were introduced to Understanding the Brain, Part 1: Becoming a Learning Scientist have elected to offer the workshop to their teachers, and some have made a districtwide commitment, choosing to delve deeper into brain-based learning by integrating it into their yearlong professional development plan for teachers’ grade bands.

Evolving with each new partnership, Part 2: Applying Neuroscience to My Classroom and Part 3: Extending Brain-Based Learning in My Practice are extensions of the first workshop offered at the Franklin Institute, developed under a model of collaboration between teachers and museum educators. Following teacher participation in Understanding the Brain, Part 1, the Franklin Institute’s staff, key administrators (e.g., superintendent, principal, curriculum director, science specialist), and selected teachers representing the targeted grade bands meet together for half a day to plan Parts 2 and 3. As part of this brainstorming, these teachers take a leadership role in shaping and leading parts of the upcoming workshops, and connecting neuroscience to real-world classroom contexts with their peer educators. Critical to sustained application of brain-based, research-to-practice training is a connection to each school’s curriculum and district priorities. This is accomplished by collaborating with the representative teachers from each grade level to identify additional topics of interest that resonate with them and their district peers. Sample topics have included the effect of curiosity on the brain, multisensory learning, the impact of taking breaks on learning, social and emotional dynamics, and metacognition.

Enabling select teachers to take a leadership role in guiding their peers cultivates teacher capacity and empowers them to sustain these efforts, with the ultimate goal of engendering significant changes in teacher culture and practices across a district. Specifically, teacher leaders identified some of the ways in which the research-based strategies presented in the first workshop have begun to be implemented in classrooms. They reported that:

-

"Incorporation of brain-based activities has impacted my students heavily in the way of engagement and meaningful learning.” —Sixth-grade teacher

-

"I’ve paid much more attention to how students need to be moving every so often to accomplish the best learning.” —Sixth-grade teacher

-

"I’ve learned how to phrase comments/feedback so that they are growth mindset–based.” —Third-grade teacher

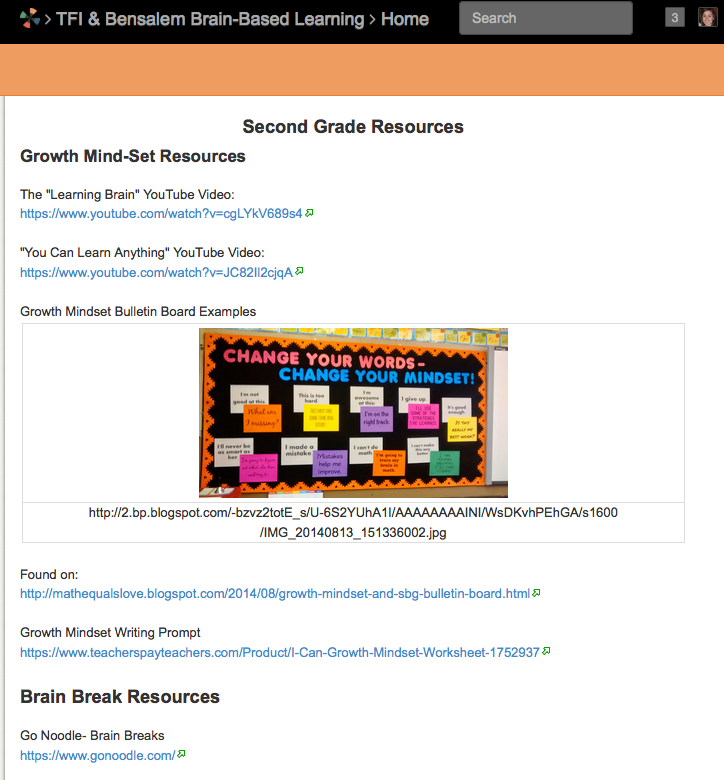

As the teachers lead breakout groups with their grade-level partners across the district, they discuss teaching practices, strategies, and activities that embody the themes learned earlier. For example, teachers have shared technology-based, free resources such as www.gonoodle.com, which provides brief active breaks from learning that can help shift children’s attention and allow them to expend some physical energy.

Sustaining Brain-Based Learning in Practice

The Franklin Institute is committed to helping educators further explore and sustain practical application of brain-based strategies and has developed a number of resources that support the Your Brain exhibit. These include the Your Brain Exhibit Educator Guide and Your Brain Exhibit Research Sheet (available at www.fi.edu/exhibit/your-brain). A one-page framework was also developed for educators to use during and after the workshop. It highlights the key ideas and recommendations from neuroscience research, which teachers can use as a lesson-planning supplement to make sure they continue to acknowledge best practices. For example, because cognitive science research shows that accessing prior knowledge and experience is a key strategy that allows students to make connections to new information, the framework asks teachers to consider, when developing a specific lesson, “How will students share their related knowledge and experience?” This encourages teachers to address important brain-based strategies as they plan learning experiences for students. The Franklin Institute has also worked with districts to establish a Wikispaces Classroom site (see Figure 1) where the Franklin Institute’s staff and district teachers can share brain-based resources and articles within a private community. Helping teacher-leaders share concrete examples of classroom activities and demonstrations with their peers provides opportunities for collaborative, integrated curriculum development and allows teachers to demonstrate ownership over how they apply brain-based strategies.

Evaluation of School Impact

Evaluation Methods

A postworkshop survey was administered to all participants (approximately 1,000 to date). Participants were asked to rate on a five-point scale the content and quality of each component of the workshop and their level of agreement with several statements about learning outcomes and future plans (e.g., “After participating in today’s program, I understand more about learning and memory in the brain” and “I plan to apply what I learned today to my practice”). These were followed by several open-ended questions to probe deeper (e.g., “What skills and/or knowledge did you learn in this program that you will take into your work?” and “What steps will you take to apply what you learned today to positively impact learning for students, teachers, and/or administrators?”).

In addition, a subset of participants (N = 63) in the Part 1 workshop was evaluated externally via a survey by the Goodman Research Group. Closed-ended questions asked participants to

- rate their level of agreement with statements about the quality and value of the workshop (e.g., “The PD was clear and understandable” and “The PD was well matched to my PD needs”);

- compare their knowledge, retrospectively, about neuroscience and the brain both before and after the workshop; and

- rate the extent to which the workshop prepared them to incorporate brain-based teaching strategies and help their students get the most out of a potential field trip to the exhibit.

Among the open-ended questions, participants were asked to report what they learned that was new to them, recall the three main brain-based teaching strategies presented, and identify the most useful part of the workshop.

Evaluation Results

Holding districtwide PD workshops at a museum has been a novel experience for both museum and school district partners. When surveying teachers and administrators who attended the brain-based PD (N = 400), 94% responded that they understood more about how learning and memory work in the brain and that they planned to apply what they learned in the PD to their practice as a teacher or administrator. At the museum, teachers are able to step out of their day-to-day routine and mindset; in the Part 1 external evaluation, 37% answered that the exhibit experience was the most useful part of the workshop. Many teachers visited the museum during their own childhood, so after returning as adults, they recalled long-term memories associated with positive emotions and active learning, immediately producing heightened enthusiasm and curiosity—which, in fact, reinforces several core concepts about brain-based learning. Administrators report that teachers tend to be more open to ideas presented in this off-site, informal format, are less distracted, and are more engaged.

Unique to this PD program is its applicability and appeal to a broad range of educational contexts. Teachers, out-of-school facilitators, and youth group leaders have all expressed in evaluations that they benefited from this rich and diverse opportunity to integrate a designed museum experience, science content, and pedagogical strategies in ways that allow application in both formal and informal settings. For example, participants mentioned that the exhibit showed them how “intense” concepts could be made fun and understandable for students. Others cited that learning how memory works and how it can be improved will make it easier to find techniques that will help students.

The value of this neuroscience, research-to-practice PD approach appears to be in providing teachers with evidence-based information, strategies, and informal hands-on experiences that can be applied in numerous ways to teaching multiple subjects and ages. Teachers have the opportunity to advance their knowledge in an area that is crucial to educating children; 18% of participants reported that before the workshop they knew “quite a bit” or “a great deal” about neuroscience and the brain, while 69% rated their knowledge at this same level afterward. Teachers feel encouraged and have expressed feeling validated by the discovery that strategies they believed to be successful in their classroom are supported by neuroscience research, providing a new lens through which to focus on their work.

For Parts 2 and 3 of the workshops, evaluation data show that the combination of some learning guided by the Franklin Institute and some by peer teachers created varied learning settings allowing for different, but equally relevant, types of discussion. The Franklin Institute provided education on the areas in which we were uniquely positioned to do so, and the teachers likewise facilitated professional learning in the areas in which they were experts. This model is now being replicated as we scale up to long-term partnerships with multiple school districts.

This model is an outgrowth of the Franklin Institute’s National Institutes of Health–funded educational outreach programs to support the Your Brain exhibit, including professional development efforts to support teachers in using the exhibits with their classes. The interest of a local superintendent in building a comprehensive, districtwide commitment to brain-based learning and embracing growth mindset helped to further the Franklin Institute’s development of this more extensive, multiyear professional development effort. The result is a list of offerings, now shared with administrators from multiple districts, that include a variety of workshop packages, each with a related fee structure. School districts partner with the Franklin Institute in planning single or sequential professional development days, as allowed by their annual professional development budgets.

Conclusion

Science centers have the unique role of being able to translate complex science to the public using hands-on exhibits and programs that engage an audience through experiential learning. Schools have the formidable challenge of teaching and supporting children’s learning in comprehensive, multidisciplinary ways that are distinct from what informal institutions provide. However, the science of brain development, learning, emotion, and memory is an important area of overlap between these complementary domains.

Together, museums and school districts have a unique opportunity to partner with one another to provide professional development experiences that translate relevant research to practice that draws upon the resources and culture of schools in meaningful, relevant ways. In the current school climate, where teachers are constrained in so many ways, attending professional learning that integrates advances in education and neuroscience research can greatly impact teaching and learning. Allowing teachers to visit museums as part of their professional growth can reinvigorate their appreciation of museums as centers of learning and develop community partnerships that support advancement in their practice.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research under grant 1R25DA033023-01. We also thank Dr. David Baugh and the Bensalem Township School District for their partnership in piloting these programs and Alexis Kiesel for her review of the document.

Dale McCreedy (mccreedy@fi.edu) is vice president of audience and community engagement at the Discovery Center at Murfree Spring in Murfreesboro, Tennesee. Jayatri Das (jdas@fi.edu) is Chief Bioscientist at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Julia Skolnik (jskolnik@fi.edu) is Manager and Curriculum Specialist at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Feature

Working at the Intersections of Formal and Informal Science and Literacy Education

Connected Science Learning March 2016 (Volume 1, Issue 1)

By Becky Carroll and Tanya Baker

The National Writing Project provides professional development, develops resources, generates research, and works to improve the teaching of writing and learning in schools and communities.

In this article, we invite you to expand your vision of what it means to work at the intersections of formal and informal science and literacy education by describing how educators have collaborated to create programs that blend science and literacy in schools, in museums, and across these two spaces. In 2012, K–12 teachers from the National Writing Project (NWP) began working with the Association of Science-Technology Centers (ASTC) and science museum educators in the National Science Foundation–funded Intersections project, which is being evaluated by Inverness Research. NWP is a network of sites, anchored at colleges and universities, that serves teachers across disciplines and at all levels, from early childhood through university. NWP provides professional development, develops resources, generates research, and works to improve the teaching of writing and learning in schools and communities.

Intersections is currently in its fourth year and is made up of 10 partnerships between NWP sites and ASTC museums, which design and implement projects at the crossroads of formal and informal education and of science and literacy learning. These partnerships also share their work across the Intersections network (which includes all 10 partnerships, ASTC, NWP, and Inverness Research), as well as beyond the NWP and ASTC communities. Intersections takes the word literacy at its broadest meaning, including writing, writing strategies, writing education, professional development strategies, and digital storytelling. The project also investigates the terms science and literacy quite broadly. The project asks, “What does combining these two domains look like in professional development for formal and informal educators and in experiences for students, youth, and visitors to museums.

The project focuses on creating a network of local partnership sites, with an emphasis on partnerships first, projects second. Intersections did not set out to create a “one-size-fits-all” model for local science and literacy programming. Instead, it provides guidelines and ongoing feedback for the design and implementation of programming that fosters the partnership sites’ locally appropriate and innovative projects. The resulting 10 projects vary in their emphasis and focus: Some focus solely on professional development for formal and informal educators, whereas others include students, youth, and museum visitors as primary audiences. The range of programming is a significant result of Intersections and includes projects that focus on a variety of topics (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Focuses of the Intersections Project

| Project Focus | Partnerships Exploring This Focus |

| Making and Tinkering | Charlotte, North Carolina Raleigh, North Carolina |

| Youth Programs Youth Development |

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Phoenix, Arizona Fort Collins, Colorado Boise, Idaho Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania |

| Educator Professional Development K–12 and K–16 Professional Learning Communities |

Missoula, Montana San Diego, California Charlotte, North Carolina Raleigh, North Carolina Boise, Idaho |

| Production-Centered Design (e.g., games, apps, videos) | Orono, Maine Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania |

| Place-Based Work | Missoula, Montana Orono, Maine Phoenix, Arizona Fort Collins, Colorado San Diego, California |

Work in the Intersections

In this article, we highlight two examples of Intersections projects that involve rich formal and informal collaborations—one in San Diego, California, and one in Charlotte, North Carolina. Both examples involve:

- a professional community of educators that includes K–12 teachers, informal educators, and university faculty;

- deep dives into areas of mutual interest and need among the professional community; and

- benefits for the partnership institutions, as well as participating educators and their students.

Through their interventions and reflections on those interventions, the educators in both partnerships learned about what makes science and literacy learning more powerful in and across formal and informal spaces.

San Diego: At the Intersections of Formal and Informal Education

The bus pulled up in front of the Reuben H. Fleet Science Center as much-needed rain pelted down. Excited fifth graders poured from the bus into the rain, ready to explore. And waiting just inside was a group of classroom teachers and museum educators, ready to watch closely and think carefully about how these students’ teachers and chaperones support student learning and promote student inquiry during [a] field trip. —Kim Douillard, Project Leader

Members of the San Diego Intersections team—staff from the Reuben H. Fleet Science Center and the San Diego Natural History Museum, partnered with San Diego Area Writing Project (SDAWP) teachers—have spent the last two years investigating the following questions: What is the purpose of school field trips to museums? What are our goals for them? How can we best accomplish those goals? What strategies for improved literacy teaching and learning can we adopt from NWP to enhance the field trip? What can writing-project educators learn from informal educators that can inform their experiences with field trips and work in their classrooms?

In the project leaders’ minds, the field trip represented an important entry point for students to form a lasting relationship with science museums and science itself, in addition to being a piece of shared work between museum and school educators. Formal and informal educators in the San Diego partnership wondered how they might improve field trips to move beyond static museum guides, which tend to assume that all students have the same background knowledge and leave with the same extended learning, to a more interactive framework that supports formal and informal educators in planning and implementing field trips that propel student learning both during and after the field trip.

To study the field trip as a shared problem of practice, leaders from the Reuben H. Fleet Science Center and San Diego Natural History Museum each enlisted five informal educators and SDAWP leadership invited 10 local K–12 teacher consultants to participate in the project. The group of informal and formal educators met for multiple four-hour sessions over the course of two years between 2013 and 2015. Much of the work of this ongoing professional learning community, especially in the first year, focused on getting to know one another and understanding the problem of practice—improving the field trip—from one another’s point of view. This was no small task. One museum educator recounted leaving a first meeting with tears in her eyes to tell a colleague, “The teachers don’t feel welcome at our museum.” A teacher shared, “And they told us, nicely of course, that we don’t take advantage of the field trip.” (Read the reflections of one of the museum educators on the Intersections team.)

This could have been the end of the partnership, but facilitators worked carefully to scaffold these professional conversations so that participants could remain open to hearing each other. Additionally, there was real desire on both sides to improve the field trip. That kind of shared inquiry into the work fueled the team during times of difficulty.

This team also engaged in evidence-based conversations built from its use of ethnographic tools (see examples below) to observe field trips in action. Project leaders noted the importance of formal and informal educators working as teacher-researchers during the project, testing and developing new tools for improving field trips as a first step but, more importantly, observing students in the museum trying the new tools. The teacher-researchers used (1) an action observation chart, which asked observers to note specific actions (e.g., pointing, asking a question) taken by visitors in particular rooms in the museums and (2) a map of the exhibit, which the observer could use to follow a particular youth, mark where he or she stopped and engaged, and code different kinds of engagement.

The teacher-leaders noticed that in San Diego, writing is probably the most powerful science-learning tool for improving the field trip experiences. Using the observation tools above, the team noticed a deepening of student engagement, intentionality, and understanding when they were encouraged to write before, during, and after the field trip. As a result of these findings, the team began to eliminate complicated study guides, replacing them with “swag bags” that contained blank paper and colored pencils. The teacher-leaders also decided to substitute simple question-and-answer prompts on a worksheet with a “take five” activity, during which everyone simply stopped to write. Students returned from the museum with ideas for their own projects, inspired by something experienced during the field trip and the opportunity to write about that experience. Participating educators and students wrote blog posts about their field trip experiences. Included are links to two student blogs, one from second grade and one from a third grader.

The following vignette is from an observation of one high school group’s interactions in the museum and the discussion among the teacher-leaders of what they had observed:

The students wandered in pairs or small groups through the exhibit. All teacher-researchers plus the leaders observed and recorded students’ experiences. Students seem engaged in some aspects of the exhibit, less so or superficially interested in others. After about 45 minutes, some of the students wandered into other sections of the museum and answered the other, more formal questions on their handouts specifically related to an exam they would have the following day. During this time, their teacher noted that she is surprised that many of the students seem more interested in other parts of the museum [that] are less hands-on. She wonders [if it is] peer pressure? The age of the students? She said she wanted to talk to them at lunch to urge them to discover more deeply, to return to parts of the exhibit that interested them and not to be self-conscious. After the students departed, the group of educators discussed the following:

- Student interactions and engagement and what might be impacting [these], as well as what students took away from experience that couldn’t be seen or measured, [such as] comprehension from reading.

- How high school students were more inclined to use their phones to take photos (and how that reality could be incorporated into a visit to make it more meaningful and reflective) and how they were less inclined to engage in sustained discourse with each other and to play or to stay in one place for a long time.

- How the teacher sets up the visit makes a difference, [as well as] how open-ended the expectations for the visit activities are and how much the students’ interests in the task …

- How being able to see student work (both from the museum and from the classroom afterwards) will help both the formal and informal educators better determine the impact of the museum/field trip experience.

- What both formal and informal educators can do to help students figure out how to take their own initiative in the museum field trip and grain broader learning from the experience.

One project leader noted, “[In this project,] teachers get to observe students who are not their own … They are free to watch [students] interact without judgment, and this is powerful. They are more apt to notice how students are engaged, are learning.” Over time, the growth and development of the educators and their ability to engage in collective inquiry was a significant outcome of this team’s work.

Benefits to participants

It seems clear to us that our process of learning together contributed to the changes in both teachers’ and museum educators’ practices when it came to field trips. The most powerful agent of change was the opportunity for educators to watch students in action with materials and practices they developed. We learned that the teacher bringing her students is often so worried about student behavior, that keeping students busy with a worksheet seems like a valuable exercise. It is when she has the opportunity to step back and see her students through her own eyes as a researcher that she is reminded of her goals for students beyond the trip itself. —Kim Douillard, project leader

Ongoing, formative-evaluation interviews with participating formal and informal educators have shown that they liked the authentic experience of working together and trying to solve the very real issue of field trip quality and impact. In evaluation interviews, they noted the benefit of coming to know “someone from the other side.” Furthermore, teachers liked learning about the inner workings of a museum, particularly exhibit and visitor experience design, whereas museum educators said it was eye-opening to learn how addressing the diverse needs of teachers and students can have big impacts on improving museum-visit experiences. All of the educators also learned from their early toolkit-development process and observations about what it means to design inquiry experiences for students.

Students of participating educators enjoy enriched field trip experiences that are catalysts for additional learning and have better learning experiences in school. One teacher spoke about changes in her approach to taking students on museum field trips, as well as how her teaching overall has been influenced as a result of the project: “My goal for field trips has changed completely. I approach them with a more student-driven perspective, and what I ask students to do on the field trip and after has changed as a result of the project. Everything I do is different now … I have a more open-ended stance; my questioning has changed, I give my students more choice, more flexibility, provide more opportunities for inquiry in my classroom.”

The partnership expanded the relationship and collaborative potential between the writing project and the museums. All four partnership project leaders said they would welcome the opportunity to work together again. The partnership also strengthened the ability of each institution to bridge the informal and formal worlds and to work in crosscurricular ways.

UNC Charlotte: Making at the Intersection of Arts and Sciences

The Charlotte Intersections project, called Making STEAM, is a partnership between Discovery Place and the University of North Carolina at Charlotte Writing Project (UNCCWP). This project was born out of the institutions’ shared values and work history, as well as common interests within the leadership team, all of whom believe deeply in the integration of arts and sciences. Making STEAM focused on “making” in both the school and the museum settings. As one project leader explained,

We explore ‘making’ as a concept, as way of teaching, and as a set of actions requiring literacy, science, mathematics, engineering, technologies, and creativity to engage students in the learning of science through literacy and technology-rich experiences. By ‘maker,’ we mean what Dale Dougherty in his TED talk calls ‘curious, enthusiastic amateur inventors whose tinkering habit sparked whole new industries.’ A ‘make’ in this project invites students to play with, try out, or represent ideas through physically and digitally making things and then sharing drafts in progress in various ways ([e.g.,] Google+, Twitter, classrooms, face-to-face forums). Makes in this project are science content– and literacy-rich. Makes bring science learning and literacy together by following the recursive processes of writing: launching an idea, composing, reflecting, sharing, and looping back and around.

The project involved informal educators from Discovery Place, who teamed with pairs of teachers in three different Charlotte-area schools (a writing project teacher-consultant and a science teacher at each school). These groups of three worked in schools to guide the writing project teacher-consultant’s and science teacher’s students through make cycles, weeks-long activity cycles in which students, the pair of teachers, and the informal educators were engaged in making activities focused around specific themes (e.g., wonder, play, and curiosity) in both their science and language arts classes. These themes were also extended to activities completed at the museum during field trips and special events. Students then shared their collective work through an online Google+ community group that was open to all participating teachers and students, university students of UNCCWP faculty, and the members of the Intersections project network. One participating educator, Steve Fulton, explained an example of a paper-engineering activity that took place in his classroom:

Most recently, we played with paper engineering and pop-up books. The project grew out of novels students were reading in my eighth-grade ELA [English language arts] class. The novels, which all fell in some way under the broad theme of ‘injustice,’ were read by students in small book club groups, or literature circles. Toward the conclusion of their novels, students brainstormed themes and subject matter related to the text that they felt [were] important to their lives and/or community, and used this area of interest as a starting place for both research and creative writing. Building a pop-up book required students to be able to do more than write a compelling narrative; they would also need some familiarity with the mechanisms commonly employed [in] creating [pop-up books]. Robby Stanley, the informal educator from Discovery Place, collaborated with the science teacher, Mrs. Green, to transform her classroom for a few days into a paper-engineering workshop. With plenty of scrap paper, scissors, and markers on hand, the two teachers guided students as they worked through iterations of each of the four mechanisms commonly used in pop-up books: pull tabs/sliders, flaps, layers, fold-outs, and wheels. On the days … students tinkered with paper in science class with Robby and Mrs. Green, they were finishing and sharing their creative writing pieces in my class, negotiating collaborative groups and the stories that their books would feature, and beginning to storyboard the individual pages. While all students were creating a similar form, how they crafted that pop-up book—from the story it told [to] the pop-up mechanisms it employed [and] the ways illustrations supported and interacted with both—was up to them. What was also up to them, and perhaps the greatest challenge, was how … to make this all happen as a group. The students created these stories that were inspired by readings in both their science and their language arts classes … so, the content worked its way in, both in the books that they made and in the process they went through to make them. The way that they composed the books gave them experience with both doing science and doing literacy. It was the most rigorous experience with composition that has ever taken place in my classroom.

Students also participated in and facilitated making experiences for the broader community at Discovery Place and annual Maker Faires held at the local children’s library. As one teacher wrote,

We brought the affordances of the science museum’s informal learning structure to the formal learning environment of public schools through making, and we remade the school field trip to the science museum so that students were actively participating in and contributing to the science museum.

Benefits to participants

Ongoing, formative-evaluation interviews with participating formal and informal educators show that both benefit from the project in myriad ways. Both are learning more about making and how to integrate making into their respective education spaces. The classroom teachers become familiar with science content and the engineering design processes, project planning, and informal learning strategies from the museum educators, whereas the museum staff learn from the NWP teachers’ writing strategies that they are incorporating into other museum education programs. For example, on one recent field trip, one of the formal educators participating in the project asked his students to facilitate making and science learning experiences for other visitors. Students helped demonstrate how to make stop-motion animations at a museum station; other students shared the pop-up books they had made in their science and language arts classes and facilitated pop-up engineering activities for other visitors. From observing these young facilitators, museum staff learn how to connect with and draw visitors into facilitated experiences.

Both formal and informal educators became more comfortable with implementing making projects in their settings. As one project leader noted in a formative interview, the educators apply making principles to include writing as a form of making and recognize less-obvious science and literacy intersections. For example, one participating English teacher spoke about how the interdisciplinary work, combined with a focus on making, has spread beyond the activities in the project to other areas of his teaching:

The underlying principles of making—the open-endedness, the student self-directedness—I have pulled and worked into other class assignments, too, and changed the way I teach and the way my students go about learning. When students know they have to figure things out, and I am there to support them; the whole dynamic of my class changes throughout the whole year. And when the learning that happens in science class intersects with learning in language arts class, where students can translate their learning from one class to another, it has gotten more kids engaged. And the students take what they do when they are making and apply it in their science work and in their language arts work. When we have the space for students to make, where it isn’t scripted and the notion of trying again is a big part of it, their attitude[s] change. When they have a problem in front of them in science class, they aren’t as afraid of not having the right answer or not getting it right the first time. And this translates to the writing my students are doing—they are more likely to jump in and get words down on paper. So this gives the students the chance to think about how the skills they are learning through [making] are the same skills they need to be writers, scientists, and learners in general.

Many of these ideas and practices have spread throughout the museum culture as well, as “the educators who participated in this program share their learning with those who did not have the privilege,” notes Gábor Zsuppan, a project leader. Informal educators are incorporating strategies learned from their writing-project colleagues into other programs they run at the museum. For example, one informal educator said:

I am able to take what I am learning with this and apply it more directly because I am the camp coordinator and I write all of the summer curriculum. So, I am starting to bring in more literacy-based activities, like writing reflections on camp activities, to our science camps.

Participating educators have reported to evaluators—and formative-evaluation observations corroborate—that students of the formal educators have been highly engaged throughout and have benefitted, both from their integrated science-and-literacy-through-making experiences, as well as their deeper relationship with Discovery Place. Students shared how powerful they felt it was to have subjects that were normally taught in separate classrooms taught together. For example, high school students reading 18th-century novels in their English class were asked to create 18th-century theme parks based on their novels. Their projects, made from cardboard and other simple materials, highlighted one particular invention of the era and the physics or engineering behind that invention. They were assisted in this process through the coteaching of the English teacher, a writing project teacher-consultant, and an informal science educator from Discovery Place. The theme park activity was complemented by a field trip to the museum, where students explored phenomena through their interactions with exhibits that tied back to what they had been learning in physics and making in English class. As one student described:

The museum was really interesting. We walked by and there was this [museum program] on momentum and we were just doing momentum a few days ago (in physics class). We saw inventions and we were just talking about some of the inventions of the 18th century and so that kind of tied in with that and it was nice. At the Discovery Place we definitely saw connections in the things that we got to play with. A lot of those were based off of things that we learned in physics.

Another making activity students engaged in was creating a visual map of a poem in one class period (Figure 2).

Figure 2

A student group’s representation of a Sylvia Plath poem

The value of this process is described by one of the students:

When you read [a poem], and you think about it, you might pull out a few things, but when you have to actually create something, you can’t just have one idea or one symbol because that is boring. So you have to pull out a bunch of different symbols and make them relate and you will find that the author does that, but you usually don’t see it until you dig deeper. So it is a really cool and fun way to get you to really dig deep about the poem.

These students valued the combination of science and literacy: Another student said:

The integration of subjects has been great, because we think that subjects are very boxed, confined into their own little compartments and they don’t really mingle. So we are using physics in our projects, and doing the engineering part of it, and we are writing about our projects, and we are creating and we have all of these different pieces to make this one whole … I learned that it is difficult at first and you might not really know where to start, but once you do, you find your way and realize that it is not really 12 different subjects, it is just really one subject.

I had never done a lot like it, actually having physics in English, together … I feel like I learned more this semester than I have in my past two years.

Lessons Learned

In its first three years of work, the Intersections project has already touched the lives of many people—nearly 300 preK–12 formal educators, over 150 informal educators, and over 700 youth have participated in these 10 projects. Formative evaluation has focused not only on gathering data about the nature and quality of these local projects and the experiences of and contributions to participants, as we have highlighted in these two cases, but also on the feasibility, strengths, and challenges of the local partnerships, as well as the work and the benefits of the network. (Summative evaluation of the program will take place in the winter and spring of 2016.)

The work and evaluation of the Intersections project show, and the two cases in this article highlight, that perhaps most significantly, the project has fostered professional learning communities on multiple levels. On a national level, the partnership between the NWP and ASTC has created opportunities for these two organizations to learn from one another about facilitating local partnerships and providing high-quality professional development. In addition, meetings and sessions at the two organizations’ annual national conferences have provided opportunities for members of the broader informal STEM and literacy education communities to learn about innovative science-literacy programming. Additionally, the two organizations’ work in other areas (e.g., NWP’s Educator Innovator community, ASTC’s communities) has allowed the network’s participants to connect into other, larger communities engaged in similar efforts.

On a local level, the partnerships between writing-project sites and science centers have engaged in and learned from designing and implementing locally appropriate science-literacy projects. These projects have fostered ongoing opportunities for leaders of these organizations and the participating formal and informal educators to inquire into many different subject areas, from place-based education to fostering youth development through science and literacy, fostering curation, and better understanding best practices in product-centered design. In some cases, they have also engaged professionals from other local schools and community-based organizations in their efforts, such as citywide science festivals, after-school programs, local poetry organizations, art museums, and libraries.

Becky Carroll (bcarroll@inverness-research.org) is a senior researcher at Inverness Research in Inverness, California. Tanya Baker (tbaker@nwp.org) is Director of National Programs at the National Writing Project in Berkeley, California.

“Engineering Habits of Mind” Empower Performance: Featured Presentation at #NSTA16 Nashville

By Guest Blogger

Posted on 2016-02-29

Not long ago, engineering was an academic subject mainly reserved for college students. But as states put new science standards in place, many elementary teachers face the expectation that students must learn engineering concepts and skills starting as early as kindergarten. Can you really teach engineering to very young students? I’ve been working in the field of K-12 engineering for more than a decade, and based on my own research and that of others, the answer is a resounding yes. I’ll be talking about this at the NSTA National Conference on Science Education in Nashville later this month. Below are a few points I’ll be making.

Seeing Is Believing

This video (“We’re Going to Make a Hand Pollinator”) lets you take a peek inside a Minnesota classroom where first-graders are working as agricultural engineers, designing a device to pollinate flowers by hand. (This kind of technology is sometimes used in orchards and greenhouses when native insect pollinators aren’t available to do the job.)

When this “hand-pollinator” activity is introduced to elementary teachers in a professional development workshop, someone inevitably raises a hand to say, “This challenge is too sophisticated for young children!” But as you can see in the video, these first-graders relish the assignment. And as they design and test their hand pollinators, they use the same practices as working engineers. They problem-solve, use analytical thinking, demonstrate their creativity, collaborate effectively, and communicate clearly.

Here’s something else to notice: These students are engaged in hands-on learning, manipulating real objects. There are no on-screen simulations–no computers or tablets required. The takeaway is that, at the elementary level, you can provide students with genuine engineering experiences using inexpensive craft supplies like pompoms and pipe cleaners, making classroom engineering practical even at schools with budget constraints or limited access to the internet and digital technologies.

Engineering Is a Must

Engineering is more than just do-able—it’s something your students SHOULD do. Our research finds that classroom engineering makes a difference. When young children engineer, they learn science concepts and practices more effectively than when they study science alone, and they also develop greater interest in STEM careers. The findings hold true for ALL children: girls and boys, of all races and ethnicities, with different physical and cognitive abilities, from varied socioeconomic backgrounds, and English Language Learners.

These are exciting outcomes. But there’s an even larger impact. When young students engage in hands-on engineering, they develop what educators now call “engineering habits of mind.” The term “habits of mind” itself is not new. Science for All Americans, a report published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, defines it as “the values, attitudes, and skills that shape our outlook on knowledge and learning.” But the notion of engineering habits of mind has its origins in a special committee convened by the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the National Research Council (NRC) to explore the question, “How should K-12 engineering be taught?”

Be Persistent and Learn From Failure

The committee’s report, released in 2009, laid out a vision based on three principles; one was that to be effective, classroom engineering activities should help students develop engineering habits of mind, or positive attitudes about learning that the practice of engineering specifically helps to develop—for example, an openness to considering multiple solutions (as our young agricultural engineers demonstrated above), or, in the video at right, the ability to be persistent and learn from failure.

This video (“Put a Sponge in It!”) captures a scene in a fourth-grade classroom in Fall River, Massachusetts where students have been working in groups to design a model of a water-permeable membrane that, when installed in a terrarium-like habitat, will let in enough water to keep a frog’s skin moist—but not so much water that the habitat floods. Watch the teacher circulate from group to group as the students test their membranes. Some designs fail—the water pours right through.

Despite these failures, the students are engaged and smiling. And in the end, it’s a student, not the teacher, who cheerfully says, “We definitely have to improve.” From the way the students mention the different materials they can use to engineer membranes, you can tell they’re not daunted at all—they’re already thinking about what their next design might be.

Dr. Christine Cunningham is a vice president at the Museum of Science, Boston and the founder and director of Engineering is Elementary® (EiE). Developed at the Museum’s National Center for Technological Literacy®, EiE is an award-winning curriculum and professional development project designed to integrate engineering and technology concepts into preschool, elementary, and middle school science lessons; the project has reached an estimated 10 million children and 100,000 educators nationwide. Join Cunningham in Nashville on March 31, from 3:30-4:30 pm, when she’ll present the Mary C. McCurdy Lecture: Integrate to Innovate: How Classroom Engineering Develops “Habits of Mind” That Empower Student Performance, in the Music City Center, Davidson A1, at the NSTA National Conference on Science Education.

Dr. Christine Cunningham is a vice president at the Museum of Science, Boston and the founder and director of Engineering is Elementary® (EiE). Developed at the Museum’s National Center for Technological Literacy®, EiE is an award-winning curriculum and professional development project designed to integrate engineering and technology concepts into preschool, elementary, and middle school science lessons; the project has reached an estimated 10 million children and 100,000 educators nationwide. Join Cunningham in Nashville on March 31, from 3:30-4:30 pm, when she’ll present the Mary C. McCurdy Lecture: Integrate to Innovate: How Classroom Engineering Develops “Habits of Mind” That Empower Student Performance, in the Music City Center, Davidson A1, at the NSTA National Conference on Science Education.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2016 National Conference

2016 STEM Forum & Expo

2016 Area Conferences

Follow NSTA

Teaching on the record

By Mary Bigelow

Posted on 2016-02-29

My mentor wants to video my middle school science class. I’m not having specific problems with students and I think my lessons are good, but this still makes me nervous. Why would she want to do this? —G., Minnesota

My mentor wants to video my middle school science class. I’m not having specific problems with students and I think my lessons are good, but this still makes me nervous. Why would she want to do this? —G., Minnesota

Actually, your mentor may be doing you a favor by introducing you to a meaningful professional development activity.* You can reflect on a lesson without watching a video of it, but sometimes memories are selective. If we remember a few students misbehaving or being confused, we may see the entire lesson as a failure. Or we may overlook the quiet students and later assume that everyone was engaged and participating. We may be unaware of distractions. We may mistake a lack of questions as a sign students understood the lesson.

You and your mentor should check that recording a lesson for the purpose of teacher development is acceptable in your school and with your teachers’ organization, the video is meant for your eyes only, and it is not an evaluative tool for you or for students. Based on your mentor’s guidance, you may also want to inform students that they will be part of the video but it will not be shared with anyone else.

My preservice science methods class had a video component. (This was in the days of cumbersome VHS equipment, before cell phones or hand-held cameras!) A classmate recorded the video and then we would critique ourselves. We shared the videos and our reflections with the professors for their feedback, too. It was win-win—we had experience making a video as well as critiquing our own. I learned that I used many “aahs” and “ums,” which I chalked up to being nervous, but I needed to be aware of this vocal tic. I focused more often on one side of the classroom and most of my questions were at the factual level, two things I needed to address during student teaching. I decided I needed to be more mobile and circulate more when students were working individually at their tables or in small groups.

Your mentor may have a protocol for viewing and reflecting on the video, and here are some suggestions from my own experiences on both sides of the camera:

First, look at it from your perspective. Get this out of the way! Consider your voice level and tone, eye contact, gestures, speech patterns, appearance, and vocabulary. Don’t be too hard on yourself at this point, unless there’s something that would interfere with student learning or the structure of the lesson.

Second, look at the video from a student’s perspective. Was there a lot of down time at the beginning or end of the class period? How did the transitions between activities work? Did some students not participate? Were students beyond your gaze off-task? Could students hear and see what they needed to? Were there any distractions that interfered with the lesson (e.g., announcements over speakers, noise from the outside), and how did you deal with them to keep students focused? Did you recognize students who had their hands up? If you monitored group work, did all groups get some attention? How did you handle groups who needed more attention from you? Did some students get more attention than others, and if so, why?

Third, look at the video one more time and reflect on effective practices you used. Were students aware of the goal of the lesson? How well did the activities align with your curriculum? Did you pose questions on a variety of levels? Did students use safe lab procedures? How did you incorporate wait time? What evidence shows that students worked effectively in their groups? What strategies did you use to get all students engaged in the lesson? What formative assessments did you use, and what did you learn from them? What kind of feedback did you give students? Did the lesson turn out the way you thought it would? What might you do differently?

Another thought is to share the video with the class for their input, explaining that you are using it to become a better teacher. What do they see that you may have missed?

Your mentor may appreciate your returning the favor by recording her class. It would be interesting for you to see how an experienced teacher reflects on a lesson.

*Three reasons why teachers should film themselves teaching

My mentor wants to video my middle school science class. I’m not having specific problems with students and I think my lessons are good, but this still makes me nervous. Why would she want to do this? —G., Minnesota

My mentor wants to video my middle school science class. I’m not having specific problems with students and I think my lessons are good, but this still makes me nervous. Why would she want to do this? —G., Minnesota

Nine Ways Science Teachers Can Make the Most of #NSTA16 Nashville

By Carole Hayward

Posted on 2016-02-29

As you make your plans for NSTA’s National Conference in Nashville, take a look at this diverse array of events and opportunities designed to enrich your experience. (If you haven’t registered for the conference yet, what are you waiting for? Here’s information on how to register.)

NSTA’s conference offers many specialized opportunities for science educators. Find the ones that are right for you, and register for them today. Some events are free and others have a cost attached, but most require separate registration or tickets. Start planning now, so you don’t miss out. See you in Nashville!

|

Teaming Up for STEMBring a team to the conference, and NSTA will customize the conference experience for you and your team by engaging with you before, during, and after the conference to focus your STEM implementation efforts. Learn more! |

|

|

|

NGSS Train-the-Trainer WorkshopKick start the NGSS teacher training in your district with this March 30-31 workshop. Attendees will receive and use the e-book, Discover the NGSS: Primer and Unit Planner. Space is limited, so sign up today. (Also, join us for two free NGSS@NSTA events: the Forum and the Share-a-Thon.) |

|

The Northrop Grumman Foundation PLI Scholarship ProgramIf you are attending the conference, your school or district is within 200 miles of Nashville, and your student population has high needs, submit your application to be considered for a scholarship to a March 30 PLI. |

|

|

|

|

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Future NSTA Conferences

2016 National Conference

2016 STEM Forum & Expo

2016 Area Conferences

Follow NSTA

Reading aloud, asking questions and engaging in discussion

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2016-02-27

“Do you remember Moomintroll?” my sister asked me recently. Moomintroll, a beloved Finnish character from the works of artist and author Tove Jansson, was introduced to us in an unusual picture book sent to our family by our aunt Kitty. The Book about Moomin, Mymble and Little My had a differently shaped hole cut in each page that provided a tantalizing peek at what came next in the story of Mommintroll’s journey— enough to provide information for a guess but not enough to be certain. Populated with Gaffsie and a fillyjonk, the book’s fantastic illustrations made the guessing more challenging than realistic pictures would have. And the text on each page explicitly invited the readers to guess by ending with a question, “What do YOU think happened then?”

“Do you remember Moomintroll?” my sister asked me recently. Moomintroll, a beloved Finnish character from the works of artist and author Tove Jansson, was introduced to us in an unusual picture book sent to our family by our aunt Kitty. The Book about Moomin, Mymble and Little My had a differently shaped hole cut in each page that provided a tantalizing peek at what came next in the story of Mommintroll’s journey— enough to provide information for a guess but not enough to be certain. Populated with Gaffsie and a fillyjonk, the book’s fantastic illustrations made the guessing more challenging than realistic pictures would have. And the text on each page explicitly invited the readers to guess by ending with a question, “What do YOU think happened then?”

Issuing an explicit invitation to think about what might happen means inviting a child to ask additional questions of herself—Could this happen? Could that happen? Might thus and so happen?—while she mulls over her answer. An adult asking a child a question, but not answering it, is leaving room for the child to actively think about the answer.

I often asked questions in my work as a preschool science teacher. At the beginning of the school year, some children politely sit and wait for the answer, not out of shyness but because they think that it is their job to wait for the adult to tell them the answer. How can we create an atmosphere where children will take on the responsibility of answering questions, and then asking them?

Reading books aloud in a dialogic reading style may be one way to inspire children to actively think about a question. Reading aloud continues to be an important part of building children’s oral language and vocabulary, listening comprehension, content knowledge, concepts of print, and alphabet knowledge and phonological awareness in elementary school (see “The Book Matters! Choosing Complex Narrative Texts to Support Literary Discussion” by Jessica L. Hoffman, William H. Teale, and Junko Yokota in Young Children). The authors urge us to choose books that have “rich and mature language—words and phrases that develop complex meaning and imagery,” “an artful, synergistic blending of text and illustration,” and “an engaging, complex plot”–all aspects that are strong in The Book about Moomin, Mymble and Little My.

Another book with these characteristics and also lends itself to asking children to guess, or predict, is Fortunately by Remy Charlip. A delightful roller coaster of a book with a pattern of alternating “fortunate” and “unfortunate” pages, it is particularly well-suited to getting children started thinking about what happens next in a book, noticing patterns, and asking questions. Most of us need multiple opportunities to practice asking children to predict what will happen next in the story without adding our own comments. Be clear that you want the children to predict or guess, and that you will respect and accept all answers. Their answers do not have to agree with what you might say or with each other. At the end of the story ask the children if things turned out the way they predicted to encourage them to reflect on their guesses.

Another book with these characteristics and also lends itself to asking children to guess, or predict, is Fortunately by Remy Charlip. A delightful roller coaster of a book with a pattern of alternating “fortunate” and “unfortunate” pages, it is particularly well-suited to getting children started thinking about what happens next in a book, noticing patterns, and asking questions. Most of us need multiple opportunities to practice asking children to predict what will happen next in the story without adding our own comments. Be clear that you want the children to predict or guess, and that you will respect and accept all answers. Their answers do not have to agree with what you might say or with each other. At the end of the story ask the children if things turned out the way they predicted to encourage them to reflect on their guesses.

I never predicted that Moomin and Mymble would be vacuumed up by a big Hemulen but it didn’t surprise me when the full-of-mischief and resourceful Little My helped them escape. Although not every book is designed to elicit questions and guesses with each turn of the page, every book offers a chance to predict at least once in the story. Try using the style of dialogic reading with your children the next time you read aloud to them.

I never predicted that Moomin and Mymble would be vacuumed up by a big Hemulen but it didn’t surprise me when the full-of-mischief and resourceful Little My helped them escape. Although not every book is designed to elicit questions and guesses with each turn of the page, every book offers a chance to predict at least once in the story. Try using the style of dialogic reading with your children the next time you read aloud to them.

Beetles before butterflies

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2016-02-25

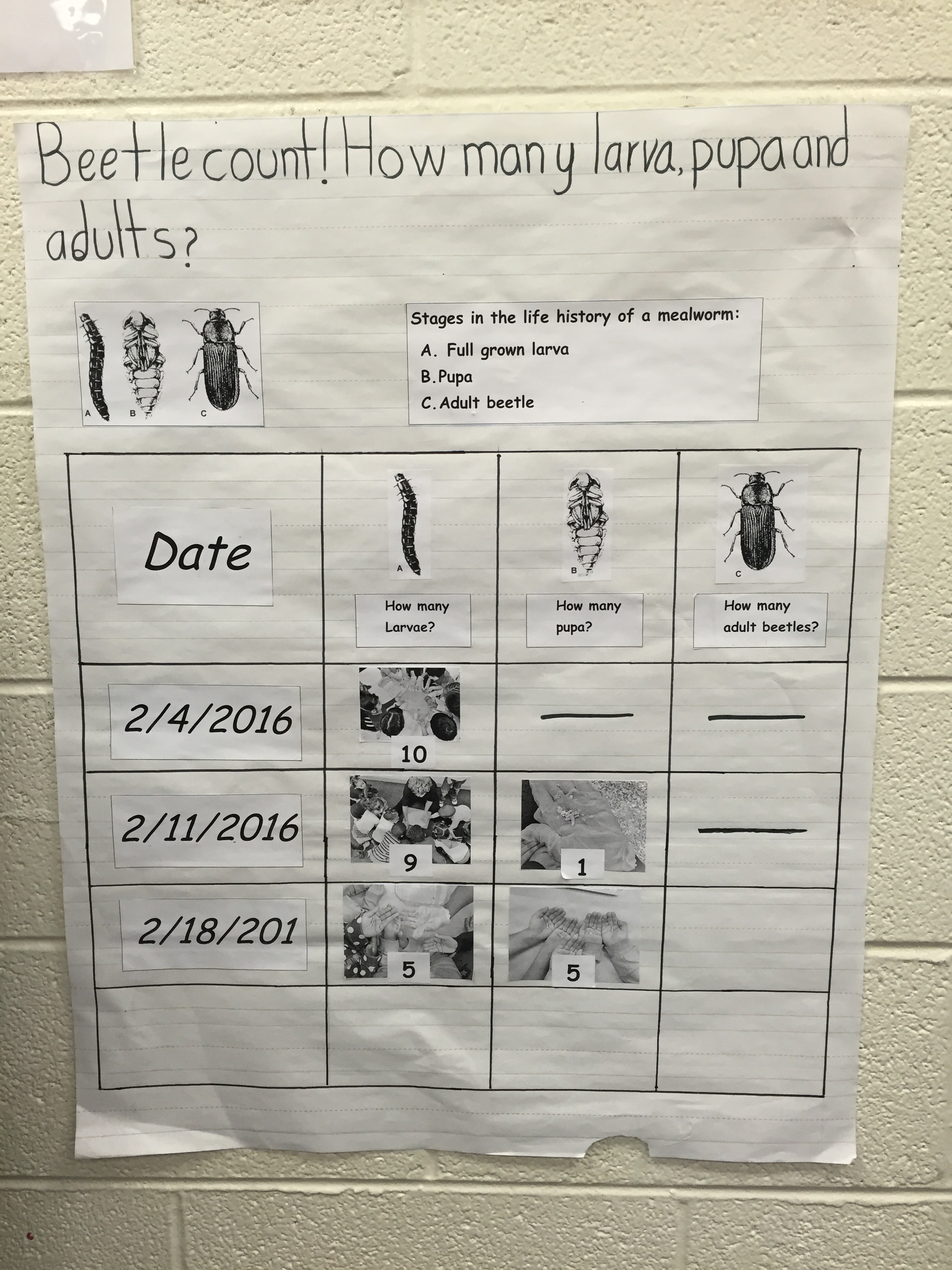

To prepare children to be close observers of the small animals that will be more easily seen in spring, I bring a container-habitat of beetles into the classroom during winter months. These Tenebrio beetles and larvae (widely known as “mealworms” although they are not worms) will live in the container, not colonize your classroom. Beetles in the classroom in a closed container, or on a tray, allows children to make hands-on observations of an insect as it changes from the baby form, a larva (like a caterpillar) to a pupa (like a chrysalis) to an adult beetle (like a butterfly). Observing more than one kind of small animal over time—isopods (roly-polies), gastropods (snails), insects, and others—introduces the diversity of animal life and provides multiple opportunities for children to build their understanding of living organisms.

To prepare children to be close observers of the small animals that will be more easily seen in spring, I bring a container-habitat of beetles into the classroom during winter months. These Tenebrio beetles and larvae (widely known as “mealworms” although they are not worms) will live in the container, not colonize your classroom. Beetles in the classroom in a closed container, or on a tray, allows children to make hands-on observations of an insect as it changes from the baby form, a larva (like a caterpillar) to a pupa (like a chrysalis) to an adult beetle (like a butterfly). Observing more than one kind of small animal over time—isopods (roly-polies), gastropods (snails), insects, and others—introduces the diversity of animal life and provides multiple opportunities for children to build their understanding of living organisms.

Observing and caring for beetles also prepares children to observe and care for caterpillars in spring. Because children do not watch the larvae (baby beetles or caterpillars) continuously, they may not understand that a pupa or chrysalis is not a new animal but just a

Observing and caring for beetles also prepares children to observe and care for caterpillars in spring. Because children do not watch the larvae (baby beetles or caterpillars) continuously, they may not understand that a pupa or chrysalis is not a new animal but just a  new form of the baby insect that they have already seen. One way to support children’s developing understanding is to have them count the number of larvae in the Tenebrio beetle container-habitat every few days. How many babies can we find in the container? If you start with just 10 beetle larvae, children will be able to find all ten without losing interest. They can record their count (data) on a chart. Through regular observations and counts, children will notice when they find a pupa instead of all larvae. Their wonderings about this new form is an opportunity to wonder along with them and encourage them to draw to record their discovery.

new form of the baby insect that they have already seen. One way to support children’s developing understanding is to have them count the number of larvae in the Tenebrio beetle container-habitat every few days. How many babies can we find in the container? If you start with just 10 beetle larvae, children will be able to find all ten without losing interest. They can record their count (data) on a chart. Through regular observations and counts, children will notice when they find a pupa instead of all larvae. Their wonderings about this new form is an opportunity to wonder along with them and encourage them to draw to record their discovery.

Ms. Althea Pope, preschool teacher, made a poster size chart and added images of the children as they counted, further documentation that supports children’s view of themselves as practicing science. As children draw their observations of the insects over time they notice more and more details and become more comfortable with handling them.