Three Ways to Be an NSTA Volunteer

By Carole Hayward

Posted on 2018-10-11

Volunteering is often considered a valuable asset on a resume or CV for almost any profession, including educators. Professionals of any age can develop new skills, expand professional networks, and open doors to opportunities for career growth through volunteering.

Get involved in shaping the future of NSTA by participating in one of the following three options: standing committees, advisory boards, or panels. With more than 30 different topics, you are sure to find an opportunity to spark your interest.

Each volunteer opportunity involves a different time commitment. You might want to consider starting with a committee and then working your way up to an advisory board. But choose a topic that interests you and consider getting involved.

Standing Committees

Standing Committee volunteers review NSTA policies, programs, and activities on an annual basis. Although there are 14 different committee topics, these committees are further broken into three subsets:

- Level: Volunteers review and report on whether the organization serves the interests of educators at four levels of science teaching: preschool/elementary; middle level; high school; and college.

- Function: Volunteers review the impact of NSTA’s work on roles outside the classroom, such as coordination and supervision; informal science; multicultural and equity issues; preservice teacher preparation; and professional development.

- Task: Volunteers review internal and external NSTA tasks and processes behind activities such as awards and recognition; budget and finance; nominations; and organizational auditing.

Committee members work directly with members of the Board of Directors and can have a positive impact on science education at the national level.

Advisory Boards

Have you ever wanted to submit an idea for improvement to an NSTA journal, conference, or program? Do you have a great inkling for innovation in urban science or special education? Advisory Board members have the opportunity to give direct input, guidance, and advice to members of the NSTA staff and the Board of Directors.

More than 15 different Advisory Boards cover the breadth of the organization:

- Publication Advisory Boards

- Science and Children Advisory Board

- Science Scope Advisory Board

- The Science Teacher Advisory Board

- Journal of College Science Teaching Advisory Board

- NSTA Reports Advisory Board

- Aerospace Programs Advisory Board

- Conference Advisory Board

- Development Advisory Board

- International Advisory Board

- Investment Advisory Board

- John Glenn Center for Science Education Advisory Board

- NGSS@NSTA Advisory Board

- Retired Members Advisory Board

- Rural Science Education Advisory Board

- Science Matters Advisory Board

- Science Safety Advisory Board

- Special Needs Advisory Board

- Technology Advisory Board

- Urban Science Education Advisory Board

Panels

Members who volunteer on Panels are charged with joint selection for specific NSTA programs, including the following:

- Outstanding Science Trade Books Panel

- Best STEM Books Panel

- Award Panel

- Shell Science Teaching Award

Volunteers bring outside perspectives and professional experience to NSTA programs, products, and activities, so consider taking your membership beyond reading your journal or attending a conference. Volunteers are essential to the success of NSTA. Join our team of volunteers by completing the online application by December 3, 2018. NSTA President-elect Dennis Schatz will make appointments through the end of the year, and notification will begin at the end of February 2019. These appointees’ term of office begins on June 1, 2019.

Not an NSTA member? Learn more about what our membership has to offer. We would love to have you join us!

Follow NSTA

Volunteering is often considered a valuable asset on a resume or CV for almost any profession, including educators. Professionals of any age can develop new skills, expand professional networks, and open doors to opportunities for career growth through volunteering.

Vernier: Go Direct Force and Acceleration Sensor

By Edwin P. Christmann

Posted on 2018-10-11

Introduction

The Go Direct™ Force and Acceleration Sensor couples a 3-axis accelerometer with a stable and accurate force sensor that measures forces as small as ±0.1 N and up to ±50 N and can be used in the classroom or outdoors.

The Go Direct™ Force and Acceleration Sensor connects wirelessly via Bluetooth® or wired via USB to your platform. Subsequently, there is no longer the need for an intermediate interface to link directly to a PC, Mac, Chromebook, or mobile device. Adding to its portability, it hold a charge for two hours, providing a myriad of opportunities for authentic data collection in the classroom, laboratory, and out in the field. Moreover, the Graphical Analysis 4 App allows for battery life monitoring and seamless interfacing.

The Go Direct™ Force and Acceleration Sensor includes a force sensor, 3-axis accelerometer, and 3-axis gyroscope.

What’s Included

• Go Direct™ Force and Acceleration

• Hook attachment

• Bumper attachment

• Nylon screw

• Accessory Rod

• Micro USB Cable

Classroom Applications:

Go Direct™ Force and Acceleration can be used in a variety of experiments:

• Unpack Newton’s Third Law by linking the hooks of two force sensors with a rubber band.

• Utilize the force sensor to pull an object across a surface profile to measure frictional forces (refer to the media link at the end of the review).

• Attach the force sensor to the Vernier Centripetal Force Apparatus to measure centripetal force and acceleration simultaneously.

• Position sensors on Dynamics Carts to investigate forces and accelerations in collisions.

Examples of Data Collection

Image 1. Time and Force

Image 2. Time and Force

Image 3. Newton’s Third Law

Specifications

• Force: ±50 N

• Acceleration: 3 axis, ±16 g

• Gyroscope: 3 axis, 2000°/s

• Connections: Wireless: Bluetooth, Wired: USB

For more information and a demo experiment click here:

https://www.vernier.com/experiments/msv/29/frictional_forces/

Cost- $99

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Example of Impulse and Momentum Activity (option 1) – https://www.vernier.com/experiments/pep/6/impulse_and_momentum/

Introduction

The goal of this activity is to relate impulse and momentum, and to determine that the impulse is equal to the change in momentum. The investigation is set up in two parts. First, students will evaluate how to quantify the event that causes a change in motion (i.e., impulse). The second is to develop a model for how impulse changes the velocity or momentum of an object.

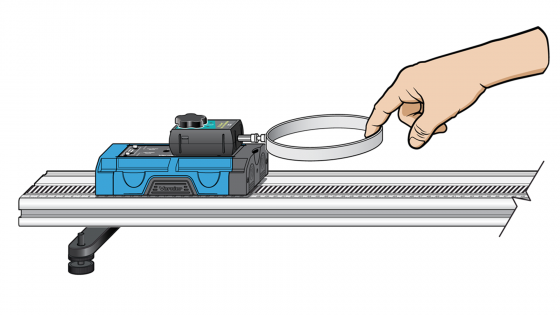

In the Preliminary Observations, students observe a cart experiencing an impulse, using a hoop spring on a force sensor to change the momentum of a cart. Students address impulse in Part I of the investigation.

In Part II, students address the question of quantifying the change in the motion state of the cart. Students who investigate the relationship between impulse and change in velocity should find that the constant of proportionality is about equal to the mass of the cart. Students who investigate the relationship between impulse and change in momentum should find that the two values are nearly numerically equal.

Learning Outcomes

•Identify variables, design and perform investigations, collect and analyze data, and draw a conclusion.

•Determine impulse and change in momentum based on measurements of force and velocity.

•Create a mathematical model of the relationship between impulse and the change in momentum.

Sensors and Equipment

Next Generation Science Standards

Disciplinary Core Ideas

•PS2.A Forces and Motion

Crosscutting Concepts

•Patterns

•Cause and Effect

•Systems and System Models

Science and Engineering Practices

•Planning and carrying out investigations

•Analyzing and interpreting data

•Using mathematics and computational thinking

•Constructing explanations and designing solutions

•Science models, laws, mechanisms, and theories explain natural phenomena

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Edwin P. Christmann is a professor and chairman of the secondary education department and graduate coordinator of the mathematics and science teaching program at Slippery Rock University in Slippery Rock, Pennsylvania. Mark Hogue is an assistant professor of the secondary education department and teaches mathematics and science methods at Slippery Rock University in Slippery Rock, Pennsylvania. Caitlin Baxter is a graduate student in the mathematics and science teaching program at Slippery Rock University in Slippery Rock, Pennsylvania.

Introduction

The Go Direct™ Force and Acceleration Sensor couples a 3-axis accelerometer with a stable and accurate force sensor that measures forces as small as ±0.1 N and up to ±50 N and can be used in the classroom or outdoors.

Reggio Emilia inspiration in Science and Children

By Peggy Ashbrook

Posted on 2018-10-07

The October 2018 issue of Science and Children has a concentration of articles on early childhood science learning inspired by the Reggio Emilia approach. (This emergent curriculum approach is described on page 37 and further explained in each article.) Children’s work described in this issue includes explorations of magnetism, solids and liquids, using heat to make a change (making cookies), creating videos about sunflowers, and defining “computer” based on their experiences and prior information learning. Wow, young children have wide interests!

The October 2018 issue of Science and Children has a concentration of articles on early childhood science learning inspired by the Reggio Emilia approach. (This emergent curriculum approach is described on page 37 and further explained in each article.) Children’s work described in this issue includes explorations of magnetism, solids and liquids, using heat to make a change (making cookies), creating videos about sunflowers, and defining “computer” based on their experiences and prior information learning. Wow, young children have wide interests!

Activities include using materials to represent weather events, using print and video resources to learn about animals’ use of their environment, investigating how water can move Earth materials and how glaciers can erode and transport them, and beginning coding. Children investigated how sunlight-warmed masonry walls stored and released heat, and sponges stored and released water, while investigating how glow-in-the-dark paint worked.

Lella Gandini, professor and U.S. Liaison for the Dissemination of the Reggio Emilia Approach on behalf of Reggio Children, Italy, says, “An essential element for positive learning and teaching in the Reggio Emilia approach is to view children and teachers as endowed with strong potential, ready to enter into relationships, ready to be listened to, and eager to learn. Once we value children and teachers this way, teaching cannot be done only through imparting information, but rather, it has to be an experience in which teachers and learners construct learning together.”

Using cycles of inquiry with iterations of wonder, engage, observe, and explore, and interpret, plan, and reflect, rather than “the scientific method,” articles in Science and Children emphasize how teachers and children construct learning together. Cheryl Paul notes that documentation of children’s work helped her reflect on her role as a partner in learning, and become aware of the children’s thought processes. This helped her in the design of explorations based on the children’s interests and/or investigations that would support further learning of the concept of magnetism. While baking cookies, children construct ideas about measurement and quantity as they developed their “cookie recipe.” Jane Broderick, Rebecca Aslinger, and Seong Bock Hong write about teachers documenting their thinking about children’s thinking as a basis for facilitating this children’s  inquiry. Children’s intuitive knowledge and understanding can emerge before any related direct teaching. Anne Lowry describes how finding answers to the questions her children pursued led them to asking new questions focused on related topics. The children reasoned about electricity as they investigated how electricity moves. In Lowry’s article you can follow the thinking of children as they move from one question to a related one. Educator-researchers Sohyun Meacham and Dana Atwood-Blaine gave children an introductory mini-lesson about robotics parts and devices to support planned possibilities. They then carefully listened to children’s conversations and asked probing questions, provided paper for blueprint drawing and discussed children’s ideas with them as they drew and built Lego robots. While learning how to use illustration and video skills to document and share their understanding of sunflowers (and the questions they would like to ask sunflowers) children at The College School in St. Louis were supported in their creative process.

inquiry. Children’s intuitive knowledge and understanding can emerge before any related direct teaching. Anne Lowry describes how finding answers to the questions her children pursued led them to asking new questions focused on related topics. The children reasoned about electricity as they investigated how electricity moves. In Lowry’s article you can follow the thinking of children as they move from one question to a related one. Educator-researchers Sohyun Meacham and Dana Atwood-Blaine gave children an introductory mini-lesson about robotics parts and devices to support planned possibilities. They then carefully listened to children’s conversations and asked probing questions, provided paper for blueprint drawing and discussed children’s ideas with them as they drew and built Lego robots. While learning how to use illustration and video skills to document and share their understanding of sunflowers (and the questions they would like to ask sunflowers) children at The College School in St. Louis were supported in their creative process.

The learning described in these articles blossoms through educators’ inspiration from Reggio Emilia to foster children’s creativity as they construct learning together.

Read more about emergent curriculum in “Inspired by Reggio Emilia: Emergent Curriculum in Relationship-Driven Learning Environments” in the November 2015 issue of Young Children.

Integrating Computational Thinking and Modeling into Science Instruction

By Korei Martin

Posted on 2018-10-07

Implementing the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) is difficult. While the benefits of having students engage in three-dimensional learning are profound (we get excited when students ask new questions to investigate or explain their diagrammatic models), the demands of such rigorous pedagogy are also clear. We believe that computational thinking and modeling promote student access to and engagement in science.

Our work began three years ago when our team, comprised of science content experts, NGSS writers, curriculum specialists, and applied linguists working in collaboration with classroom teachers, began developing a fifth-grade science curriculum for all students, with a focus on English learners. The project, Science And Integrated Language (SAIL), developed a curriculum that addresses fifth-grade NGSS performance expectations in physical science; life science; Earth and space science; and engineering, technology and applications of science. Students investigate their questions to argue and explain local, relevant phenomena.

A major focus of the SAIL curriculum is students’ development and use of models. Students develop both physical models in material environments and diagrammatic models in print environments. For example, in our physical science unit, students explore the phenomenon of their own school garbage and answer the driving question, “What happens to our garbage?” To investigate this question, students develop physical models of landfill bottles (Figure 1). Each group of students puts soil, water, and garbage materials such as metal, plastic, and food into a mason jar. Half of the student groups close their landfill bottles and the other half leave their bottles open, creating both closed and open landfill bottle systems. Students observe the changes in the properties of garbage materials in the closed and open systems over the course of the unit.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Over time, students figure out that the weight of the open landfill bottle decreases because gas particles (smell), which are caused by microbes decomposing some of the garbage materials, leave the open system. Students develop diagrammatic models at different time points throughout the unit. At the end of the unit, the diagrammatic models allow students to explain the causal mechanism (microbes cause food to decompose) that is not visible in the physical models (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Overall, students use models to argue and explain using evidence. However, at the end of the unit, we realized that the physical and diagrammatic models had both affordances and limitations. The physical model proved useful for students to make observations of the changing properties of garbage materials over time in their classroom. The diagrammatic model afforded opportunities for students to represent their thinking about the observable properties and changes. Still, some students found it difficult to articulate two science ideas that were invisible to the naked eye: (1) the idea that microbes decomposed the fruit from solid particles into gas particles (smell) and (2) the notion that in the closed system, the weight didn’t change because the fruit materials were still inside as gas particles (smell). Enter computational thinking and modeling.

Computational thinking, or “a way of solving problems, designing systems, and understanding human behavior that draws on concepts fundamental to computer science” (Wing, 2006, p. 33), affords opportunities for students to make complex science ideas and processes, such as decomposition and conservation of weight, more explicit. Computational modeling allows our students to identify each component in the system (e.g., microbes, solid banana, and gas banana) and give the components computational rules of behavior and interaction (e.g., move and “run” the system) to observe emergent, whole-system behaviors (Klopfer, 2003; Wilensky, 2001).

Using StarLogo Nova, an agent-based game and simulation programming environment that utilizes blocks-based programming, students work in groups to construct computational models of landfill bottles. After being introduced to blocks-based programming through embodied activities, groups use a starter model, a model with pre-programmed components, to develop computational models (Figure 3). Students program the microbe agent, upon collision with a solid banana particle, to (1) delete the solid banana particle and (2) create the gas banana particle. Over time, the solid banana weight decreases, while the gas banana weight increases. Through the entire process, the total weight of the banana (solid banana + gas banana) remains unchanged, thus representing conservation of weight during decomposition. In short, computational modeling enables our students to visually represent the invisible process of the microbes decomposing the solid particles of the banana into gas particles (rotting banana smell). Also, developing models with peers provides a rich context for all students, including English learners, to develop computational thinking and modeling while learning science and language.

Figure 3

As expected, there are challenges when integrating computational thinking and modeling into the SAIL curriculum. Teacher and student familiarity with StarLogo Nova, instructional time, and integration of computational modeling into the science unit storyline are among them. In addition, NGSS instructional shifts are new to many teachers, and adding another layer of complexity by integrating computational thinking and modeling might seem overwhelming. However, the affordances of computational thinking and modeling make addressing these challenges a worthwhile endeavor. Through computational thinking and modeling, students have the opportunity to model unseen or difficult-to-imagine science ideas as they make sense of a phenomenon and develop their science understanding.

Computer science is now included as part of STEM education (STEM Education Act of 2015) and by 2020, one of every two jobs in the STEM fields will be in computing (ACM pathways report, 2013). Computational thinking and modeling need to be in the classroom to prepare students for the future.

References

Kaczmarczyk, L., Dopplick, R., & EP Committee. (2014). Rebooting the pathway to success: Preparing students for computing workforce needs in the United States. Education Policy Committee, Association for Computing Machinery.(ACM, New York, 2014). http://pathways. acm. org/ACM_pathways_report. pdf Accessed.

Klopfer, E. (2003). Technologies to support the creation of complex systems models—using StarLogo software with students. Biosystems, 71(1-2), 111-122.

STEM Education Act of 2015, H.R.1020, 114th Cong. (2015).

Wilensky, U. (2001). Modeling nature’s emergent patterns with multi-agent languages. Proceedings of EuroLogo 2001.

Wing, J. M. (2006). Computational thinking. Communications of the ACM, 49(3), 33-35.

Implementing the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) is difficult. While the benefits of having students engage in three-dimensional learning are profound (we get excited when students ask new questions to investigate or explain their diagrammatic models), the demands of such rigorous pedagogy are also clear. We believe that computational thinking and modeling promote student access to and engagement in science.

Archive: Embracing STEM, December 1, 2018

Science is ultimately about explaining the phenomena that occur in the world around us. Recent reforms in science education have focused on how phenomena should be used during instruction. This conference will focus on how using phenomena effectively during instruction and assessment can promote learning for all students across the K-12 spectrum.

Science is ultimately about explaining the phenomena that occur in the world around us. Recent reforms in science education have focused on how phenomena should be used during instruction. This conference will focus on how using phenomena effectively during instruction and assessment can promote learning for all students across the K-12 spectrum.

Science is ultimately about explaining the phenomena that occur in the world around us. Recent reforms in science education have focused on how phenomena should be used during instruction. This conference will focus on how using phenomena effectively during instruction and assessment can promote learning for all students across the K-12 spectrum.

Science is ultimately about explaining the phenomena that occur in the world around us. Recent reforms in science education have focused on how phenomena should be used during instruction. This conference will focus on how using phenomena effectively during instruction and assessment can promote learning for all students across the K-12 spectrum.

Ed News: There Are Many More Female STEM Teachers Now Than 20 Years Ago

By Cindy Workosky

Posted on 2018-10-05

This week in education news, new analysis reveals that the percentage of female STEM teachers has dramatically increased from 43 percent in 1988 to 64 percent in 2012; Code.org report shows that 44 states have enacted at least one policy that brings computer science education to students; NSF launches three-year, $4-million pilot for national high school engineering course; Alabama Governor calls for plan to boost STEM education; the nation is more concerned about teachers’ low pay and difficult working environment; community outreach is important for students because service show students how to apply their skills in the real world; and Nobel Laureate Leon Lederman dies at age 96.

There Are Many More Female STEM Teachers Now Than 20 Years Ago

Over the last two decades, the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics teaching field has become much more female, slightly more diverse, and more qualified, a new analysis shows. Read the article featured in Education Week.

State-Level Policy For Computer Science Education Continues To Grow

With strong policy support, adoption of computer science curriculums for K-12 students continues its steady rise, though availability in some states remains scarce, according to a report published by Seattle-based nonprofit Code.org. Read the article featured in edscoop.

NSF Launches Pilot For National High School Engineering Course

The National Science Foundation has funded a pilot to prepare a curriculum for a nationwide pre-college course on engineering principles and design. The three-year, $4-million pilot marks an important milestone in the creation of a nationally recognized high school engineering course intended to lead to widely accepted, transferrable credit at the college level. Read the press release.

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey Calls For Plan To Enhance STEM Education

Gov. Kay Ivey said she would name an advisory council to study how to improve STEM instruction in schools to meet what are expected to be strong job demands over the next decade. The governor said STEM-related jobs are expected to grow faster than overall jobs and pay a median wage about twice as high as jobs in other fields. Read the article featured on al.com.

From ‘Rotten Apples’ To Martyrs: America Has Changed Its Tune On Teachers

For years, teachers continually heard the message that they were the root of problems in schools. But in a matter of months, the public narrative has shifted: The nation is increasingly concerned about teachers’ low salaries and challenging working conditions. Read the article featured in Education Week.

Community Service & Professional Development A Winning Combination

Community outreach is important for students, not just because it’s the right thing to do, but because service shows students how to apply their skills in the real world. Service diversifies our experience and makes us process information differently by introducing us to new world views, a vital skill when problem solving. Read the article featured in eSchool News.

Leon Lederman, a trail-blazing researcher with a passion for science education who won the Nobel Prize for discovery of the muon neutrino, died peacefully on Oct. 3 at a nursing home in Rexburg, Idaho. His death was announced by the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (Fermilab); Lederman served as Fermilab’s director from 1978 to 1989. Read the article featured on the Fermilab website.

Stay tuned for next week’s top education news stories.

The Communication, Legislative & Public Affairs (CLPA) team strives to keep NSTA members, teachers, science education leaders, and the general public informed about NSTA programs, products, and services and key science education issues and legislation. In the association’s role as the national voice for science education, its CLPA team actively promotes NSTA’s positions on science education issues and communicates key NSTA messages to essential audiences.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

Teaching Abroad

By Gabe Kraljevic

Posted on 2018-10-05

I have thought about teaching internationally. Do you have any advice? How does it compare to teaching domestically?

I have thought about teaching internationally. Do you have any advice? How does it compare to teaching domestically?

—A., Iowa

I commend you for thinking about adventuring into the world! I haven’t taught internationally, so I consulted a few friends and colleagues to help put together some advice. Almost every person found teaching abroad to be an amazing experience filled with many fond memories. One of the easiest options is to apply to teach in an International School: https://goo.gl/5hwdpJ

This is their advice if you want to teach in another country’s school system:

Check certification and permits

Many governments will expedite the process for U.S. teachers who want to teach in their countries, particularly the English-speaking nations. Even so, get an early start on the certification and work visas paperwork required by most countries. In Canada, each province has its own certification. While part of the United Kingdom, both Scotland and Northern Ireland require separate certification from Britain and Wales. So, do some legwork to ensure you have everything in order. You may want to start here:

https://goo.gl/2BG1ZG

Remember, you’re the visitor!

A close friend, who taught in Australia, advises:

“Keep an open mind and be willing to look at things in different ways. The way other countries conduct business in their schools might be different from our own experiences in our country. Keeping flexible in your outlook goes a long way to fitting in.” One difference: Australian students are on a first-name basis with their teachers.

Many travellers have stories about having said or done something that they thought was innocuous but was shocking or inappropriate to the locals. Do some homework on the customs and norms of the country where you’ll be working.

Remember you will be the one with the accent! You may have to slow down, enunciate carefully and be prepared to repeat yourself. Although you may be a science teacher, being open to teaching English to non-anglophones may be an asset.

Hope this helps!

Graphic credit: Creative commons via Pixabay

I have thought about teaching internationally. Do you have any advice? How does it compare to teaching domestically?

I have thought about teaching internationally. Do you have any advice? How does it compare to teaching domestically?

—A., Iowa

Ignite The Spark of Curious Minds

By Kate Falk

Posted on 2018-10-03

With hurricane Florence bearing down on the Carolinas, I found myself in the Johnson Ice Rink on the MIT campus. I was there to be a mentor for the, IBM and other companies sponsored, 2018 HackMIT event. I was looking at more than 1,000 hackers from different schools around the globe that were actively brainstorming ideas with their teammates. As an IBM Senior Solutions Architect I was over joyed to be able to share my passion and expertise with the students as they designed solutions for natural disaster preparedness and relief.

We had many students ask about the details of this challenge and discuss the creative solutions they planned to build. I explained to them how the Internet of Things, voice recognition, visual recognition, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), and Blockchain technologies worked. I was very happy to see enthusiasm about using technology to make a great impact in the development of humanities.

The event seemed to engage the students because it was set up to reflect the educational practices that science teachers know work well and that research has shown to be effective. Students engaged in a problem-solving task that was tied to a real-world problem they cared about. They worked in groups, were able to direct their own process, and had access to expert guidance.

Watching the students at HackMIT I felt like I was going back in time to my childhood. I saw myself sitting in my elementary school’s classroom. I was looking at a magical science project. A magnesium metal ribbon was burned and emitted a bright light. I still remember the moment I saw that beautiful light, which ignited my curiosity about science. That eventually led me to the technical career path to becoming a 3-time IBM Master Inventor and AAAS-Lemelson Invention Ambassador.

I realize it is very important to encourage kids to be involved in STEM projects, to develop solutions to meaningful problems starting from a young age, and to believe they can be successful scientists, engineers, and inventors. However, while teaching science projects in my community’s school I found that not all science projects are designed to meaningfully engage students learning and loving STEM and invention.

The very first science project I taught at school is called Color Changing Milk. This experiment is easy, fun, and hands-on, but I noticed there was no intuitive way to explain all of the complex chemical theory to a group of kindergartners. The experiment was designed to be fun, but what were the students learning?

To transform the project from a fun experience to an educational activity I did a lot of research and realized that I could leverage the similarity between Legos and chemical bonds to explain what was happening during the experiment. All of the students loved the way I transformed the project and were able to grasp some of the related scientific concepts. They all cheered and even wanted to invite me to become their science teacher.

My favorite moment then and now is when the students show that they understand the concept through fun hands-on experiments. Their eyes light up and they actively participate in the conversation. They look forward to every activity and they always ask when and what the next project will be. I see future Isaac Newtons, Thomas Edisons, and Albert Einsteins from all of these curious minds.

I truly believe the next generation will be able to improve lives, if all students are given the opportunity to learn and love STEM and invention. Let’s ignite the spark of these curious minds!

Fang (Florence) Lu is a Senior Solution Architect and three-time IBM Master Inventor working at IBM Research. She has developed numerous software applications at IBM over the last 16 years, ranging from Enterprise Social Solutions to Healthcare Analytics. Florence avidly mentors and encourages other IBMers to turn their ideas into patents by hosting workshops and information sessions, and loves to inspire early professionals as they start their careers in computing.

Lu is also an AAAS-Lemelson Invention Ambassador. The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in partnership with the Lemelson Foundation manages the AAAS-Lemelson Invention Ambassador program, which celebrates the human face of inventors. Learn more about the program and the 40 Invention Ambassadors here.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

With hurricane Florence bearing down on the Carolinas, I found myself in the Johnson Ice Rink on the MIT campus. I was there to be a mentor for the, IBM and other companies sponsored, 2018 HackMIT event. I was looking at more than 1,000 hackers from different schools around the globe that were actively brainstorming ideas with their teammates. As an IBM Senior Solutions Architect I was over joyed to be able to share my passion and expertise with the students as they designed solutions for natural disaster preparedness and relief.

Combining Science and Civic Literacy

By Debra Shapiro

Posted on 2018-10-03

Students in the Citizen Science Institute, a magnet, alternative program housed at Marshall Middle School in Olympia, Washington, do scientific and civic investigations. These students are doing seasonal bird counts at the Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually Wildlife Refuge in Olympia. Photo courtsey of Tom Condon.

Why should teachers blend science with civic literacy? Because “happiness comes from being part of something bigger than yourself…Students get to understand and research community issues…[and] serve as ambassadors in the community,” asserts Tom Condon, who co-teaches the Citizen Science Institute (CSI), a districtwide magnet, alternative program housed at Marshall Middle School in Olympia, Washington. CSI involves about 60 students in grades 6–8 in rigorous scientific and civic investigations that help them “become experts who can teach other students,” Condon contends.

“We do field investigations, not field trips. Students tend to think of field trips as days off,” maintains Matthew Phillipy, who co-teaches CSI with Condon. “We work really hard. By eighth grade, students have done about 50 different investigations,” Phillipy reports.

For example, students worked with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) to track the endangered bull trout, which are native to the Northwest. “We used an idea from a Science Scope [article] about tracking endangered species using GPS [the global positioning system],” says Condon. Students explored the impact on the bull trout of a dam built in the 1940s to control floods on nearby farmland. “Dams impede their migration paths,” he notes.

When students tracked the trout, amazingly “one fish showed up at a local saloon,” Condon recalls. “Dan Spencer of [FWS]…talked about how the tracking worked and why the fish appeared near the saloon, 100 yards from the river.” Students had to weigh the benefits of the dam to farmers versus its effect on the trout. “They experience science in the field and being part of the solution,” he emphasizes.

CSI students complete two STEAM-posium (science, technology, engineering, arts, math) and civics research projects each year. Projects include a written paper and oral presentation. “We invite scientists to see what students are learning,” says Phillipy.

“The sixth graders have less experience with getting in front of people and talking. By eighth grade, they’re much more confident talking to audiences” as a result of their three-year CSI experience, notes Condon. “They serve as leaders and mentors to the younger students.”

The civics projects can focus solely on social issues or integrate science. Phillipy recalls a student with a learning challenge who couldn’t always recognize colors. “To her, it was a social issue because she was less accepted by the other students,” he explains. For her project, “she pulled in the science” by discussing what happens with the brain’s synapses with this condition, he relates.

Students find that “if you can tie in the science, it makes your arguments more relevant because you can back your opinions up with the facts,” according to Phillipy.

CSI students “learn how to behave in society. Our eighth graders leave us civically minded and understand how science works,” Phillipy relates.

The Value of Water

“I lead a series of Water Workshops with Friends of the Chicago River [a nonprofit advocacy organization working to improve the health of the Chicago River system]…called Teens H2O,” says Linda Keane, professor of architecture and environmental design at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). She established Teens H2O for students ages 11–14 because “when the water cycle is introduced in second grade, [the material] doesn’t go deep enough [for students] to understand how water gives us life…I wanted to get [Chicago-area] students to understand—[in a way that’s not always possible in school]—that we are on the Great Lakes Basin, [which provides] 84% of the surface freshwater for the United States,” she explains.

In addition, the teen years are “critical years to capture students’ [interest] before they graduate,…especially for the two-thirds of students who are not going on to college,” Keane maintains.

Once students apply for or are chosen by teachers for Teens H2O’s free workshops, “we meet them at designated places [in] downtown [Chicago]—the McCormick Bridge on the River Walk, The Chicago Line Cruise Boat Company, or SAIC—and start our water workshops. Each site has different activities,” Keane relates. Workshop themes are “Water and Me” (SAIC), “Freshwater and Lake Michigan” (The Chicago Line Cruise Boat Company, which provides an eco-cruise for the students), and “Life On, Along, Above, and Below the River” (McCormick Bridge on the River Walk).

“At first, we talk about what we need to live. Students sometimes forget air, but almost always think of water, as Chicago is on Lake Michigan. They take it for granted,” she observes, “but many of the students have never been on the river.”

Students use water interactives, simulations (water cycle, watershed, water pollution), and games (water equivalencies) to study water’s role in society. For example, they can calculate the relationship among water, energy, and climate change using WECalc (www.wecalc.org) or simulate improved water infiltration by replanting prairies, wetlands, and forests with WikiWatershed (https://wikiwatershed.org). “In WikiWatershed, they can see a map of Chicago and see the effects of heavy rainfall,” Keane points out. The workshops access material from NEXT.cc (www.next.cc), a free e-learning website Keane co-founded and directs that provides informal learning opportunities for students and teachers to explore project-based learning (PBL).

Students learn key principles in water quality and conservation while conducting field research outdoors and creating place-based projects. “We want to engage students as citizen scientists, [without them thinking they] have to be hydrologists,” Keane contends, although “we mention and they think about [science, art, and design] careers in the workshops as well. As citizens, they can do water testing and contribute” to the health of water sources.

“We show that everyone pollutes the water because of what they do. Students learn what kinds of garbage come from what businesses and why it needs to be addressed. Students learn about the role green roofs play in storm water management.” Many students, she adds, “never had thought of caring for water before or how special where they live is in relationship to freshwater.”

Most of all, they experience “science used as advocacy to make change. Helping people help others is a passion most scientists have,” Keane emphasizes.

Healing From Harvey

“A year ago, Hurricane Harvey devastated our community, flooding 16,000 homes, 3,300 businesses, and [a high school in Kingwood, Texas]. I won a grant from our district’s education foundation to coordinate a district-wide PBL on learning about, restoring, and protecting the Lake Houston Watershed. Eighteen teachers and 13 campuses in our district signed up to participate, with more teachers and students asking to participate as [we publicize] the project,” says Kathleen Goerner, secondary science coordinator for Humble Independent School District (ISD) in Humble, Texas. “People are trying to understand how [the devastation] happened and how to prevent it from happening again,” she explains.

Residents also tried to grasp why certain decisions were made, such as the opening of the floodgates by the San Jacinto River Authority, which resulted in “even more flooding; the whole Lake Houston area was devastated,” Goerner reports. Teachers told her it was important for students to understand as well. “We had lots of parent input, too,” she adds. “Harvey brought us a big community issue that everyone wants to learn about.”

One teacher who is a Federal Aviation Administration–certified drone pilot won a grant to buy drones. “He intends to have students do drone surveys of the river and lake as dredging projects proceed…I [reached out to] conservation groups in Houston…; they hope to partner with schools and provide speakers,” Goerner relates.

The hurricane coincided with changes in Humble ISD. The district traditionally hadn’t done a lot of PBL, “but this past year, several campuses brought in BIE [Buck Institute of Education; www.bie.org] for PBL training for teachers and administrators,” says Goerner. The district is also transitioning “from a traditional learning district to a more personalized learning district [in which] students have options to plan their own time and choose their own projects within a structure,” a change that aligns well with creating hurricane-related units and community projects that students will relate to personally, she observes.

Some of the teachers’ ideas and driving questions for units include Save Our Soil: How Can We Reduce the Amount of Erosion on Lake Houston?; Harvey: What Else Did He Bring to the Ecosystem Besides Water?; and Rockin’ Awesome: How Can We as Environmentalists Create a Natural Filter to Clean Our Water in Our Local Watershed Due to the Impacts of Harvey?

“We have a new superintendent who led the community in creating our Portrait of a Graduate,” which lists the traits Critical Thinker, Communicator, Personally Responsible, Creative Innovator, Global Citizen, and Leader and Collaborator. This portrait is guiding teachers in helping students learn the science behind the disaster while becoming civically engaged in the community, she relates.

“There’s still work to do; we’re not back to normal,” says Goerner. For students, “the damage from flooding doesn’t heal quickly, even if you’re back in your home. Some students are terrified of rain now.” She hopes the PBL units and opportunities for students to do conservation work will not only help them become more involved with the community, but also will give them “a way to process the flood” and heal from the trauma.

This article originally appeared in the October 2018 issue of NSTA Reports, the member newspaper of the National Science Teachers Association. Each month, NSTA members receive NSTA Reports, featuring news on science education, the association, and more. Not a member? Learn how NSTA can help you become the best science teacher you can be.

The mission of NSTA is to promote excellence and innovation in science teaching and learning for all.

Follow NSTA

Students in the Citizen Science Institute, a magnet, alternative program housed at Marshall Middle School in Olympia, Washington, do scientific and civic investigations. These students are doing seasonal bird counts at the Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually Wildlife Refuge in Olympia.